"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Five.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-04-28

In my many years flying VIPs in the U.S. government and those that followed flying business leaders from one company or another, I always got a laugh from pilots who believed they were integral parts of their passengers' lives. One of the many cabinet secretaries I used to fly often called me by my first name. "Good to see you again, James." "Nice flight, James." A few years later I saw him in the hallways of Congress and noticed a faint glimmer of recognition in his eyes but it was obvious he couldn't place my face or remember why it should be familiar.

Now, as a civilian, I recognize that we are often tempted to think we are best friends with the chief executive officer sitting about fifty feet behind us. I say all this as preface to a story about my very last flight as a pilot for Compaq Computer. After twenty years of changing jobs every few years in the Air Force, I was hoping for some stability. But that's when I found out I should . . .

Embrace Change

2001

My beloved Compaq Computer was imploding. The CEO who never had an original thought came up with a new strategy every quarter. When Dell Computer set the industry on fire with "just in time" inventory, our CEO slashed our inventories but didn't follow through with a production system to cope. When IBM decided they were a service company and not a "box" company, Mister CEO did the same with a company designed to make boxes and not service. Now he had decided that the best thing to do was to sell the entire company to Hewlett Packard, the evil empire. Now I would fly him for the last time ever, taking him from our old headquarters in Houston, Texas to the new in San Jose, California.

Not that it really matters. Compaq was my first real civilian job after leaving the Air Force and I was thrilled to fly for the company that turned the PC revolution into the game that it was today: a competitive market where prices fell and quality rose. After two years with Magic CEO at the helm all that was gone: Compaq Computers went from the industry's finest to its worst.

As pilots started to see the handwriting on the wall, the experienced hands jumped ship and we were left with three international captains, a domestic captain, and three first officers. The three of us with international bona fides were spending twenty to twenty-five days a month on the road — it wasn't much fun anymore.

I wouldn't miss the aircraft either. We had two, practically brand new, Challenger 604s. They had very nice cockpits and wide cabins. But they were always short on gas and their stubby frame made for challenging crosswind landings. And they were cheap: almost no system redundancy. In the nearly three years I had flown them for Compaq, I had been stuck all over the world. Let's see, there was Berlin with a failed hydraulic system, San Francisco with failed flaps, Taiwan with another failed hydraulic system, France with a pressurization leak, Las Vegas with a gear problem, and Alaska with a cracked windshield. Oh yes, we've left external doors all over the world as they fell off the aircraft right after takeoff. But other than that, it was a fine aircraft.

Now that our days were numbered, the pilots and flight attendants were fleeing and very few of us were left. This was my last week. At my side I would have a contract copilot I had never met and a contract flight attendant I had flown with off and on for a year. Bob and Cindy. In back was the traitorous CEO, his wife, and the last of their household possessions.

I walked down the narrow hallway from our dispatcher's office to the flight planning room and heard Cindy's voice explaining to our new contract pilot my idiosyncrasies. "You gotta do things by the book," she was saying as I entered the room. We sat for a few minutes and did our "AWARES" check required prior to every flying. Aircraft, Weather, Airport, Routing, Environment, and Signals.

"The aircraft is okay except the mach trim system is out," I began, "which means we have to engage the autopilot prior to exceeding 250 knots." Bob said he had seen that before and it was no big deal. I covered the remaining items, had another cup of coffee, and dismissed the crew for the aircraft.

Cindy was certainly competent and the smell of breakfast filled the cabin as Bob completed the interior inspection from the right seat in the cockpit. I argued a bit with the director of maintenance on reasons I needed the mach trim, but it was fruitless. He was right, of course. He couldn't very well install a spare that he didn't have. But we had a spare airplane, N255CC, which was scheduled to fly to Europe, and besides, the boss wanted his airplane, N355CC.

Mr. CEO, Mrs. CEO, and assorted luggage arrived on time and we taxied from our hangar down taxiway Whiskey Alpha on our way to Runway 15. Bob the contract pilot has double my flying time and double my time in the 604. He was a civilian pilot from day one, nice enough guy; but he may have had a bit of a chip on his shoulder flying with a retired Air Force guy. With every suggestion or comment he came back with "I know that," or "I've seen that before." No matter, it was just this flight to San Jose where we did a crew swap and I would airline home, done with this operation forever.

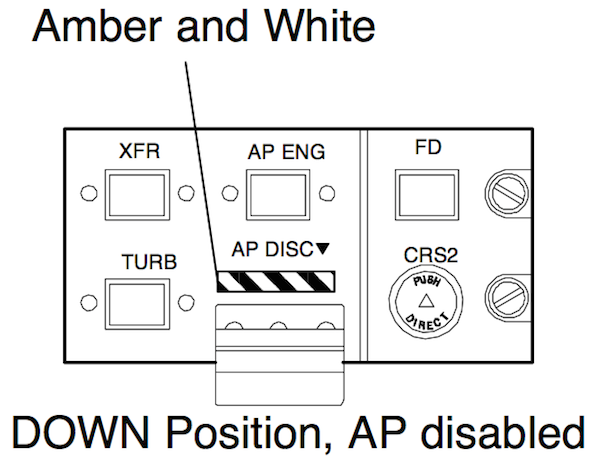

With the gear retracted and the flaps up I called for the autopilot and Bob pressed the button on the glare shield. The airplane climbed through about six hundred feet and accelerated smoothly past 200 knots. Tower instructed us to turn east for our grand circle around the airport before turning California-bound. I dialed in 090 under the heading knob of the autopilot panel and watched the airplane bank left, 10, 20, 30, and now 35 degrees of bank. I pressed the red autopilot disconnect button, nothing. "Hit your disconnect button, Bob." Nothing. Now at 45 degrees of bank. "Deselect the engage button." No reaction from the right seat. "Bob?" He was motionless, staring zombie like straight ahead. I reached over and hit the button. Nothing.

Now we had a problem. If I overpowered the flight control system, I would lose the right aileron and an emergency landing in the gusty wind conditions would be a problem. The autopilot control panel has a long, horizontal switch marked "AP DISC" which hides an amber and white hash mark. I've never used the switch or heard of anyone who has. Nobody knows why it is there because according to the book all it does is replicate the engage switch. Now at 50 degrees of bank. What have I got to lose? I slapped the switch and the roll stopped.

"Tell tower we need an emergency return, we're going to put this thing on the ground." Bob remained comatose. I made the call and reached over to extend the gear. The rumble of the undercarriage brought Bob back to life and we got busy with the before landing checklist. When I called for landing flaps, Bob pointed at his airspeed indicator which said I was doing 250 knots, too fast for flaps.

"Do you believe that?" I asked. He said nothing. "Bob, our nose is a few degrees low, the runway appears in its normal place on the windscreen, our power is set for approach, the gear is down, and I am talking to you in a normal tone of voice. If we were doing 250 knots with the gear down could you even hear my voice with the noise of the air over the gear?"

Bob shrugged his shoulders and moved the flap handle. I put our broken bird back on the ground and we dragged pax and bags to the other aircraft. We flew all to San Jose without incident. As I got off the aircraft, parked next to the Hewlett Packard hangar, Mr. and Mrs. CEO were waiting with a small gift wrapped box. "We heard you were leaving for the east coast," Mr. Company Killer said, "and wanted you to have this as a token of our appreciation." I thanked him and off they went.

"That's pretty impressive," Cindy said, "I've never seen a CEO give a pilot a farewell gift before."

"I'm nobody special," I said, "believe me."

"Oh no," Cindy interrupted, "you are definitely his favorite pilot. When we were coming around in Houston with that problem they asked me if there was anything to be concerned about. I told him that we had our best pilot flying and not to worry. They both agreed, you are our best pilot."

"That's a bit of a surprise," I said, "Even after flying him for two years and being stranded all over the world with one emergency after another, I didn't think he knew my name."

Cindy blushed.

"What?" I asked.

"Well," she said with a sheepish smile, "I wasn't going to tell you this but since you said that, uh. Well, when they were writing the card for your gift, they asked me what your name was."

Postscript

I got three job offers during the Compaq implosion and the one I picked led to a series of jobs, each better than the one before. That next geographic move has lasted thirteen years (so far) and has been the best move of them all.