"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Twenty.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-01-23

"Trust but verify" comes from an old Russian proverb, "doveryai no proveryai." President Ronald Reagan adopted the saying when signing the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty on 8 December 1987. A few years later I started applying it to all things aviation. For example . . .

1

Trust but verify — Ronald Reagan

1993

It's More Important to Look Good, Than be Good

"This radar is awful," I said as I tried to adjust the gain, the tilt, the range, and just about every other knob on the control head. "It just doesn't show any contours no matter what you do."

"Yeah," Lieutenant Colonel O'Donnell said. "They are all like that on these Gulfstreams."

It didn't make any sense. Colonel O'Donnell was also flying the Air Force One Boeing 747, but he had a lot of time on these Gulfstreams. I hadn't yet logged my 100th hour in the Gulfstream and was still in "learn mode."

"Maybe we should write it up," I said. "This is borderline dangerous."

"There's nothing to write up," he said. "The radar doesn't work because we put all that extra paint on the nose. You wouldn't want to tarnish our shiny image, would you?"

"You would rather the airplane look pretty than have a radar that works?" I asked.

"Now you got the idea," he said. "That's how we do things at the 89th.

I supposed it was plausible. The 89th Military Airlift Wing was in the business of flying the President, his cabinet, and members of Congress all over the world. Our aircraft were tools of diplomacy and each was immaculate, inside and out. But how pretty would the airplane look after we flew it through a thunderstorm?

* * *

A year later I was in Dallas, Texas wandering around an aircraft repair facility that had spent two months repainting one of our Gulfstream III, C-20B, aircraft. The airplane was hardly five years old, but with the repeated buffing, waxing, and polishing, the paint had worn thin and it was time for a new coat. The radome — the nose cone in the very front — was still propped open so the detailers could ensure the seam was perfect. I stuck my head between the radar dish and the bulkhead to see what magic existed behind the 18-inch flat plate antenna.

"Find something wrong, major?"

I turned on my heels, almost hitting the bulkhead with my head. It was the project supervisor, a civilian.

"I'm not sure," I said. "I know this radar goes on more airplanes than just our Air Force Gulfstreams, but it seems to me we are missing a few wires."

"Nah," he said, "that can't be."

I pointed to the radar dish where a plastic block with eight screws on it had eight wires going to the plate but only five to the block attached to the bulkhead. That wiring block also had eight screws with eight wires disappearing into the airplane but only five to the radar dish.

"If there are eight wires from the radar dish and eight wires from the airplane," I said, "it looks like three are missing."

"Well I'll be," he said. "Let me look at the manual." With that, he was gone. Our flight engineer tapped me on the shoulder and presented the aircraft's weight and balance paperwork and I forgot about the missing wires. Two hours later the airplane was towed out of the hangar and glistened in the Texas sun. Going through the maintenance log the last entry spoke volumes. "Replaced missing radar connections, terminals F, G, H. Built-in test mode passed."

Flying home it was like a brand new radar; the contours of each weather return was crisp and unmistakable. After we landed, I walked over to the 89th Operational Maintenance Squadron's C-20 office and found Captain Stuart Clemson, one of five maintenance officers and my next door neighbor. I gave him the maintenance log and the story of the missing wires.

"I'm on it," he said. Later that evening there was a knock on my front door. It was Stu.

"James," he said, "you aren't going to believe this. But we had five other birds here at Andrews and all five were missing the same three wires. So we called the three airplanes on the road and their flight engineers all verified they were missing all three wires. Ten airplanes, everyone of which was missing those three wires. Can you believe that?"

"Yeah," I said. "I can believe it. We've been flying these airplanes for five years now, none of their radars worked, and all the experts in the squadron said it was because of the paint. It wasn't much of a theory, was it?"

"You know what a theory is?" he asked. I shook my head in the negative. "A theory is what an expert uses when he runs out of facts."

"I'm the new pilot in this squadron," I said. "But from now on I will do like Reagan. I will trust but verify."

2018 Update

A reader suggests that this rule still applies to flying airplanes and can occur where you least suspect:

By Simon Hradecky, created Jan 19th 2018 22:50Z, last updated Jan 19th 2018 22:50Z

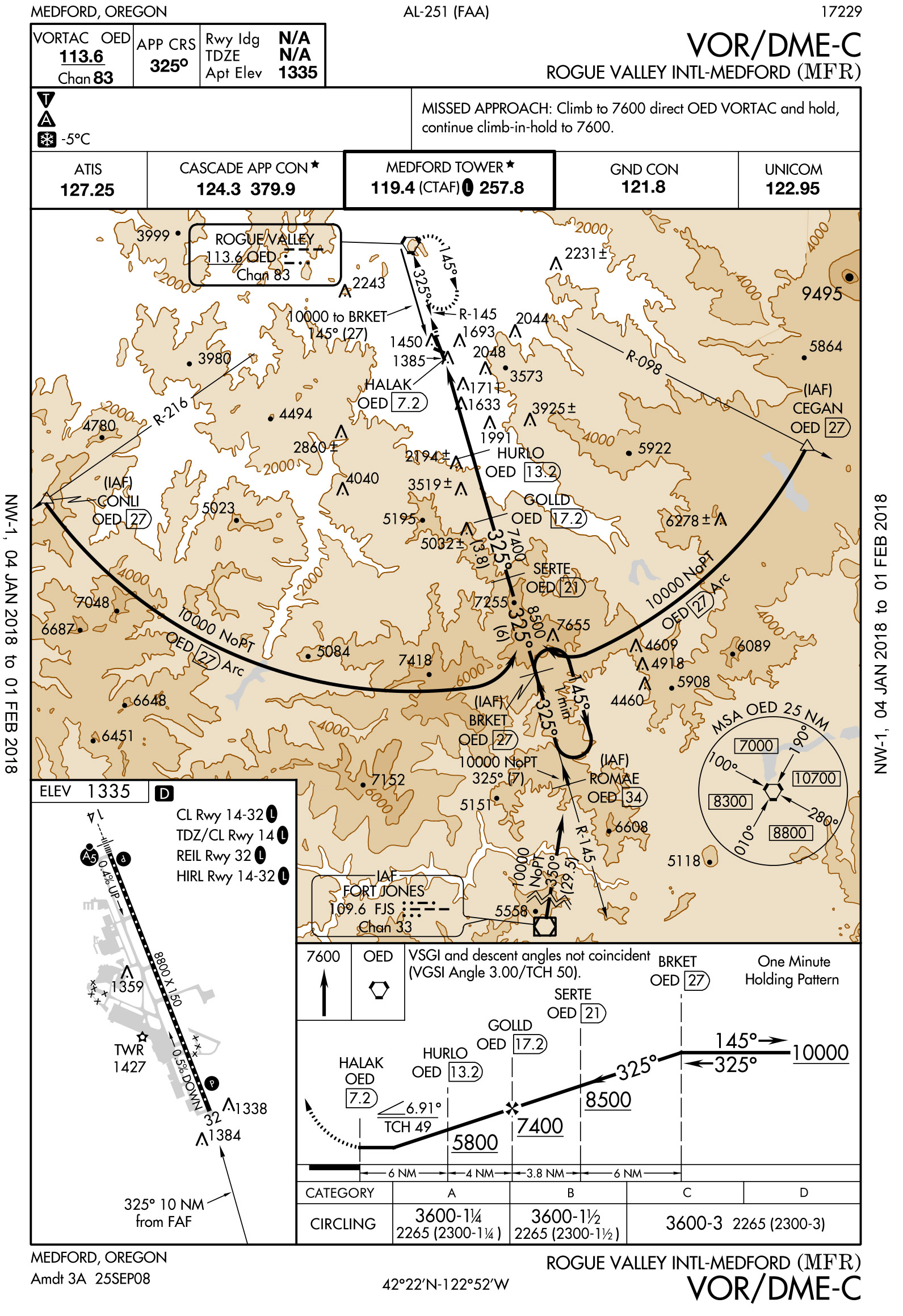

A Skywest Canadair CRJ-900 on behalf of Delta Airlines, registration N162PQ performing flight OO-3567/DL-3567 from Salt Lake City, UT to Medford, OR (USA), was on approach to Medford's runway 32 cleared for the VOR/DME C via the arc approach with the additional instruction "cross CEGAN at or above 7800 feet". The crew descended the aircraft to 7800 feet, received a GPWS warning while on the arc and climbed out to safety at 11,000 feet. A discussion ensued with ATC, the crew arguing they had been cleared down to 7800 feet, ATC stating that according to his approach plate the arc was to be flown at 10,000 feet and he had cleared them to cross CEGAN (at the beginning of the arc) at or above 7800 feet (editorial note: which includes crossing CEGAN at 10,000 feet as required by the approach procedure). The crew requested an ILS approach runway 14 and landed safely about 20 minutes after the GPWS climb.

Whomever ATC was, they got it wrong. Here is what their manual says:

[ATO Policy Order JO 7110.65U, §4-8-1 b.] For aircraft operating on unpublished routes, issue the approach clearance only after the aircraft is:

- Established on a segment of a published route or instrument approach procedure, or

- Assigned an altitude to maintain until the aircraft is established on a segment of a published route or instrument approach procedure.

NOTE-

1. The altitude assigned must assure IFR obstruction clearance from the point at which the approach clearance is issued until established on a segment of a published route or instrument approach procedure.

It seems to me if the news report is correct, a controller was acting in violation of FAA Air Traffic Organization Policy Order JO 7110.65U and should be facing the same scrutiny the pilot would have faced had the EGPWS not saved the day. I also think the pilot needs to rethink how he or she decides to accept a clearance without further thought — Trust but Verify.