The official line for all instrument pilots, not too long ago, was that a non-precision approach, one without a defined glide slope, required you to "dive and drive." Of course all that has changed with the Continuous Descent Final Approach (CDFA) but for those approaches where that is not possible, you can still use a Visual Descent Point (VDP) to keep you out of harm's way.

— James Albright

Another way to get down

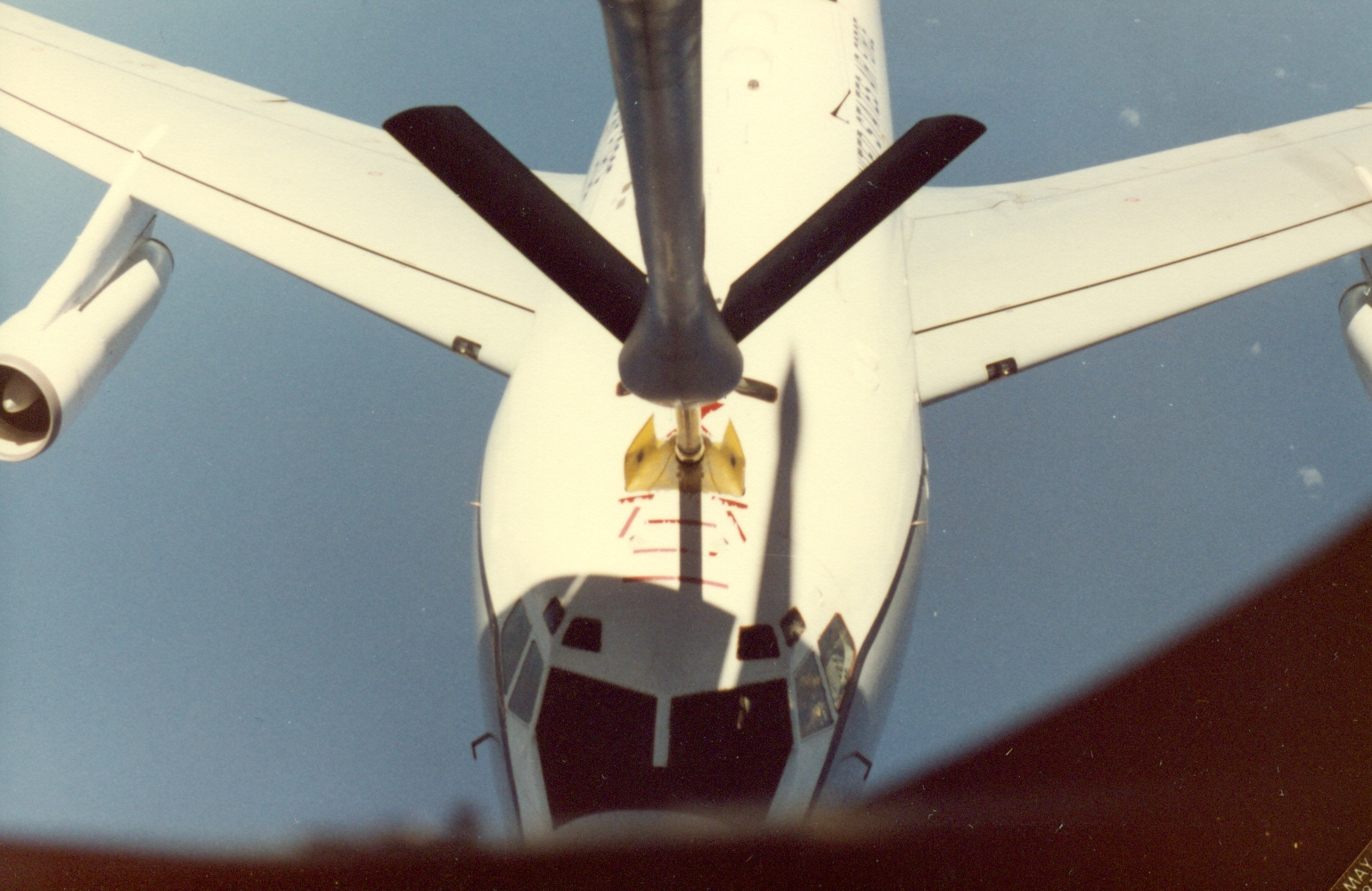

The first year flying the EC-135J was fairly low key. I had lots of time to learn new aircraft systems, receiver air refueling, Pacific theater operations; and still lots of time left over for the beach. The thing that impressed me the most about my new peers, however, was how precisely they flew the airplane down low. Takeoffs, approaches, and landings were done methodically and safely. Most of the pilots were very old—in their thirties—and with that experience came wisdom. Unfortunately, most were reluctant to pass on any of that wisdom.

“I don’t know, lieutenant,” they would say, “You just pick these things up.”

The best advice I got was from an old navigator who retired the month I got there. When I heard during the ceremony he was retiring with over 25,000 flight hours I had to ask. “Gee sir,” I must have come off, “how do you get 25,000 hours.”

“You don’t bust your butt,” he said, “if you let someone kill you, its game over.”

As my first year in the squadron came to an end the airlines started hiring and our seasoned pros started leaving. Gone were the guys who had flown into Osan Air Base, Korea a hundred times. Now there were guys just as new to this stuff as me. Things didn’t seem to be going as smoothly as they were when I showed up.

“What’s the most dangerous thing we do around here?” The safety officer asked us during our monthly commander’s call. It was a monthly requirement, but this was the first we had since I showed up, twelve months ago. Things were pretty laid back, to say the least.

“Tenth Puka chili!” Someone said from the back of the squadron auditorium. Our squadron was a secret unit on base and we were hidden behind the base 9-hole golf course. The Hawaiian word for hole is puka, the Tenth Puka was the golf club house snack bar.

“No, that’s the second most dangerous,” the safety officer said, “what is the number one, most dangerous thing we ever do in this operation?”

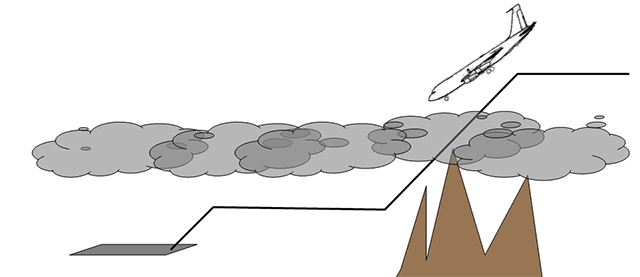

“Dive and drive,” he said, “there is nothing more dangerous than some of the non-precision approaches we fly in some of the world’s worst weather. He put a clear acetate slide onto an overhead project and showed us a hand drawn depiction of how many of us were programmed to fly our non-precision approaches.

It was true. During a precision approach, you have some kind of guidance on how to descend gracefully to the touchdown zone of the runway. During a non-precision approach, all you have is a minimum descent altitude and the desire to fly underneath some kind of cloud cover so you can see the runway in time to land. You end up diving at the ground to get down as soon as possible, pulling up the nose so as to level off at the minimum altitude, and then driving in while searching for the runway.

“What can go wrong?” he asked. The audience reluctantly threw up some of the many pitfalls.

You can dive too steeply and hit an obstacle.

You can dive so steeply that you aren’t able to pull the nose up in time to level off.

Even if you level off correctly, you can fall below the minimum altitude while your attention is devoted to looking for the runway.

You can decide to land well past the point where it would be safe to do so.

No doubt about it, the non-precision approach was an accident waiting for a place to happen.

“That’s why we use visual descent points,” somebody suggested, “you drive to the VDP and if you don’t see the runway by then, you go around.”

“That will work,” the safety officer said, “but overseas there are almost no non-precision approaches with VDPs.”

The audience fell silent.

“We figure our own VDP,” the safety officer said.

“No math!” somebody yelled, “we don’t do math!”

“Ah come on,” the safety officer said, “give it a try.”

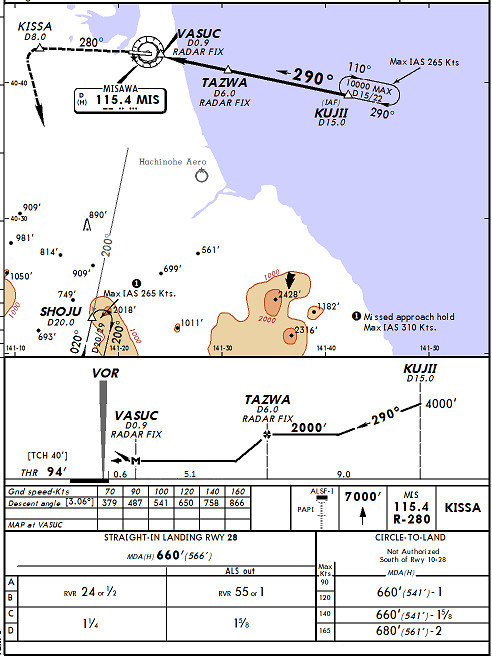

He handed out copies of an approach we had all flown into Misawa Air Base, Japan. It required you to dive down the always present cloud deck and drive into the island. If you missed, there was a mountain at the end to greet you.

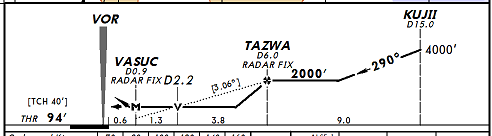

The method was simple enough. You want to be at 300 feet above the ground one mile from touchdown, 600 feet above the ground at two miles, and so on. The chart told you the minimum descent altitude was 566 feet off the ocean. Dividing that by 300 gave you 1.9 miles. The waypoint VASUC was a 0.9 DME and 0.6 miles from the end of the runway, so you could assume the DME was 0.3 miles from the end of the runway. Therefore, your VDP was at 2.2 DME. “Too hard!” somebody yelled from the audience. We all laughed.

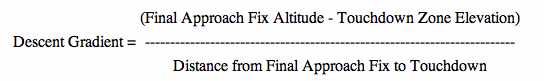

A Visual Descent Point is found by subtracting the touchdown zone from the Minimum Descent Altitude and dividing the result by 300.

Everything about figuring your own VDP appealed to me. But it only solved half the problem, the drive. What about the dive?

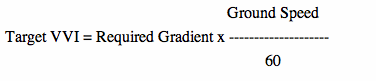

With a little bit of algebra we could get what we needed.

In the case of our Misawa approach, the required descent gradient would be:

(2000 - 94) / 5.7 / 100 = 334 feet / nautical mile

Multiplying that by ground speed in knots and then dividing by 60 to get miles per minute:

If our ground speed was 140 knots, the target VVI would be:

334 x 140 / 60 = 779 feet per minute

Target VVI on approach is the required gradient times the ground speed divided by sixty.

That would certainly be safer than screaming at the ground at well over 1,500 feet per minute, as was the normal practice. The trouble was none of this was easy to do while flying the airplane. You had to plan this ahead of time.

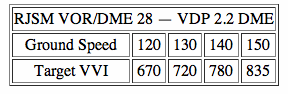

I wrote and published an in-flight guide for the squadron with cheat sheets for every non-precision approach to every airport in our normal schedule, with timing blocks so these things could be figured real time. The Misawa approach looked like this:

I practiced the method on approach several times and was satisfied it worked. I tried to teach my fellow pilots but the answer was almost universal: it’s math and it’s too hard. I was starting to compile an impressive list of formulas and math techniques to make flying easier. What I needed was a way to tie it all together. I was getting nowhere.

I got busy with my own upgrade to aircraft commander, the Air Force term for the airplane’s captain, and forgot about the issue. Fortunately, the solution would soon be handed to me.

One year later, after a run of very bad accidents in a variety of large aircraft, the Air Force decided at least one pilot per squadron needed to attend the Air Force Instrument Instructor’s school. The squadron sent me and I learned how all this math comes together. I didn’t come up with it on my own; the answer was handed to me. It had all the elegance I was looking for: 60 to 1.

A number of years later, I’m not sure when, but the world caught on that VDP’s are a good thing and almost every non-precision approach out there has one. The same approach into Misawa now has a printed VDP.

Even more years later, with the advent of global positioning satellites, more and more airports replaced these dive and drive approaches with GPS-based approaches which provided a precision glide path for those aircraft equipped to use them. The pilot sees a vertical glide path, just as if it were an instrument landing system glide slope. Technology in aviation is good.