When it comes to CRM, keep in mind: this will always be a work in progress.

— James Albright

Updated:

2022-09-19

First: a confession. I seem to write a new article about CRM every two years and the previous edition of this website had four of them. Second: It isn't my fault. The path of CRM (from Cockpit Resource Management of the past to Crew Resource Management) of the present) isn't a straight line. Third: It is only getting worse. Other professions are co-opting CRM and promise to confuse things further.

So that is why this page always seems to be under revision.

What follows is my latest attempt to bring sanity to the subject. Wish me luck.

4 — A possible solution: back to basics

5 — Another solution: learn from successful crews

1

Some history

Why we have captains and first officers

The following narrative is from the excellent book, Skygods, by Robert Gandt. It may be one of the best books on Crew Resource Management ever written. Of course it is thought more of a history of the airline than anything else. But the very concept of aircraft pilots in crew aircraft comes from the days Pan American Airways flew the majestic flying boats, just a few decades after the birth of powered flight itself.

Back in the boat days . . .

The new hires heard a lot of that during their training. Whenever someone talked about an event that happened in the first half of Pan Am's existence, his voice took a reverential tone: "Things were different in the boat days, you know. Back in the boat days we used to ... "

Everything of consequence happened then. Those were the days when Pan American took to the skies, and oceans, in its great flying boats-lumbering, deep-hulled leviathans that took off and alighted on water. To the old-timers, everything that happened after the boat days was anticlimactic. Then came the coldly efficient, unromantic land planes like the Douglas DC-4 and DC-6 and the Boeing Stratocruiser and then the antiseptic, kerosene-belching jets.

The flying boat was a hybrid-neither fish nor fowl-born of the notion that because two-thirds of the planet happened to be covered with water, it made sense to use the stuff for taking off and landing airplanes. And for a while that was the only option. Conventional land planes required long runways of thick concrete in order to take off with a heavy load. Until the late thirties, no such hard-surfaced runways existed anywhere in the world. Only the flying boat, using miles of sheltered harbor and lagoon, was able to lift the vast store of fuel required to carry a payload across an ocean.

There was also a psychological factor. Passengers took comfort in the knowledge that should calamity strike and the flying boat be no longer able to fly, it could become, in fact, a boat.

Juan Trippe, it was said, had a nautical fetish. On the walls of his home hung paintings of clipper ships, the fast full-rigged merchant vessels of the nineteenth century. It was Trippe's dream that his airline, Pan American, would become America's airborne maritime service. Pan Am flying boats would be the clipper ships of the twentieth century.

So he called his flying boats Clippers. Aircraft speed was measured in knots. The pilots who commanded the clippers were given the rank of captain. Copilots became first officers.

It wouldn't do for a Pan American pilot to look like the scruffy, leather-jacketed, silk-scarved airmail haulers of the domestic airlines. Instead, they wore naval-style double-breasted uniforms with officer's caps. When they boarded their flying boats, they marched up the ramp, two abreast, led, of course, by the captain.

Trippe understood pilots, having been one himself. He knew they were prima donnas who loved the pomp and perquisites of command. The captains of the great oceangoing, four-motored behemoths like the China Clipper needed a suitable grand title. So he gave them one: Master of Ocean Flying Boats.

Like commanders of ships at sea, the Masters of Ocean Flying Boats were a law unto themselves. While under way they exercised absolute authority over their aircraft and all its occupants. And with such authority went, inevitably, arrogance.

Source: Gandt, p. 19

A CRM History Lesson: Pan American World Airways and the Boeing 707

Juan Trippe was a visionary in many ways; he foresaw profitable international airline service before anyone else thought it even possible. He pushed aircraft manufacturers into bigger, faster, longer. You can argue that he was the driving force behind the Boeing 707 and 747 programs. Pan American World Airways and the Boeing 707 have a linked history, and that history shows just how important Crew Resource Management is in an airplane with more than one pilot.

The first three Pan Am Boeing 707s (N709PA, N710PA, N711PA), Seattle, Washington, 1958, (Public Domain)

During its lifespan, nobody crashed more Boeing 707s than Pan American World Airways. In fact, the accident rate in their first real transoceanic jet was going up while the rate for the rest of the industry was going down. There are lessons here.

Note: this list does not include aircraft involved with hijackings (24 Nov 1968, 22 Jun 1970, 29 May 1971, 17 Dec 1973).

- 3 Feb 1959 — Pan Am 115 — An inept copilot made several mistakes that plunged the aircraft into a spiraling dive. While the captain was able to recover, the question that should have been asked but wasn't is this: what about the Pan Am culture allowed such a pilot into the seat of their flagship aircraft? PILOT ERROR

- 8 Dec 1963 — Pan Am 214 — A lightning strike ignited fuel in a wing tank, causing that portion of the wing to separate; the pilots were unable to recover.

- 7 Apr 1964 — Pan Am 212 — The captain deviated from the ILS glide slope and ended up landing too long to stop on the runway. While nobody was killed, the aircraft was damaged beyond repair. PILOT ERROR

- 28 Jun 1965 — Pan Am 843 — An engine turbine disintegration caused a fire, the crew made a successful emergency landing.

- 17 Sep 1965 — Pan Am 292 — After the captain deviated from weather visually, the crew lost position awareness and descended too early into the terrain. PILOT ERROR

- 12 Jun 1968 — Pan Am 001 — The crew misset their altimeters on approach (millibars versus inches) and flew too low on approach. PILOT ERROR

- 12 Dec 1968 — Pan Am 217 — The crew flew into the ocean during approach, perhaps because of the visual illusion of the dark ocean against a dark sky. PILOT ERROR

- 26 Dec 1968 — Pan Am 799 — The crew attempted to takeoff without the flaps set. PILOT ERROR

- 25 Jul 1971 — Pan Am 6005 — The captain misflew the approach and impacted a mountain short of the runway. PILOT ERROR

- 22 Jul 1973 — Pan Am 816 — An instrument failure might have distracted the crew after takeoff; they flew a descending turn into the ocean. PILOT ERROR

- 3 Nov 1973 — Pan Am 160 — Uncontrollable smoke in the cockpit contributed to a number of CRM errors that left the aircraft unflyable. PILOT ERROR

- 30 Jan 1974 — Pan Am 806 — The crew failed to recognize an excessive descent rate caused by a recoverable windshear. PILOT ERROR

- 22 Apr 1974 — Pan Am 812 — The crew turned and descended 30 nautical miles early, opting to bet their lives on one ADF needle that had swung (indicating station passage) while the other remained steady, pointing ahead. PILOT ERROR

By the close of 1973, Pan American World Airways had lost ten Boeing 707s, not including one lost in a hijacking. (The 3 Feb 1959 aircraft was repaired and returned to service.) As Robert Gandt put it, "Pan Am was littering the islands of the Pacific with the hulks of Boeing jetliners." Pan Am initiated a study to figure out what was wrong.

As the study was being conducted, Pan Am crashed two more.

Pan Am's Corrective Action

After the crash of Pan 812 the FAA had had enough. The corrective action was necessarily severe. Pan American World Airways fully embraced the fixes and it is telling that for the remainder of their existence, they had a stellar safety record. The demise of the airline, I think, had more to do with their bet on larger and larger aircraft when fuel economy was becoming the driving force in the industry. Lockerbie and Tenerife sealed their fate. (Neither incident was due to Pan Am or its pilots.)

The Bali calamity brought Pan Am's 707 losses to eleven. Pan Am had crashed more Boeing jets than any other carrier in the world. And not just 707s. A three-engine 727 was lost during a night approach to Berlin. One of the new 747s struck the approach lights and incurred heavy damage during a miscalculated takeoff in San Francisco. Another 747 was lost to a new and still unrecognized threat. Terrorists hijacked the jumbo jet in Amsterdam, then had it flown to Cairo where they blew it up.

Something had to be done. Before the smoke subsided from the burning wreckage on Mount Patas in Bali, the probe of Pan American's flight operations had begun.

Inspectors from the Federal Aviation Administration climbed aboard Pan Am Clippers all over the world. FAA men rode in cockpits, pored through maintenance records, asked questions, observed check rides and training flights.

The inspection went on for six weeks. The FAA's findings confirmed the dismal facts that the internal Operations Review Group had already determined: Pan Am was crashing airplanes at three times the average rate of the United States airlines. Worse, Pan Am's accident rate was on the rise, a reverse of the steadily decreasing industry-wide accident experience with jet airliners.

The report was scathing. Pan Am's accidents in the Pacific, declared the FAA, involved "substandard airmen." Training was inadequate, and there was a lack of standardization among crews. The FAA's list went on to cover a host of operational items, matters of training manuals, route qualification, radio communications, and availability of spare parts.

But at the heart of Pan Am's troubles, according to the FAA, were human factors. That was the trendy new term psychologists were using in accident reports. It meant people who screwed up. When applied to airline cockpits, it had the same taint as pilot error.

With the exception of a crash caused by a cargo fire, and excluding the unknown circumstances of the Tahiti crash, every recent Pan Am accident could be attributed to some form of pilot error.

The indictment landed in Skygod country like a canister of tear gas.

Substandard airmen? Wait a minute, you bureaucratic piss ants . .. this is Pan American, the world's most experienced airline. . . we were the first to fly jets, the first to . . .

That was then, said the Feds. This is now. Clean up your act, or you will be the world's most grounded airline.

Heads, of course, would have to roll. And so they did, particularly in the San Francisco base, where the Skygod umbrella had long ago been raised over the heads of the venerable Masters of Ocean Flying Boats.

Source: Gandt, p. 115

But the most profound change was still coming. It was an invisible transformation and it had more to do with philosophy than with procedure. Pan Am was forced to peer into its own soul and answer previously unasked questions. Instead of What's wrong with the way we fly airplanes? the question became What's wrong with the way we manage our cockpits?

A new term was coming into play: crew concept. The idea was that crews were supposed to function as management teams, not autocracies with a supreme captain and two or three minions. It meant the captain was still the captain, but he no longer had the divine license to crash his airplane without the consent of his crew. Copilots and flight engineers-lowly new hires-were now empowered to speak up. Their opinions actually counted for something.

Disagree? With the captain? In the sanctums of the Skygods, it amounted to anarchy. Hadn't the Masters of Ocean Flying Boats labored for thirty years to preserve the cult of the Skygod? The barbarians were storming the gates.

But history was running against the ancient Skygods. Though Pan American technology had led the world into the jet age, Pan Am's cockpits had not emerged from the flying boat days. A new era, like it or not, was upon them. The Skygods were about to become as extinct as pterodactyls.

The cockpit transformation came down to two separate problems. The first was to de-autocratize the cockpit-to dismantle the Skygod ethic. Pan Am captains must master the subtle distinction between commanding and managing. Junior pilots must learn to participate in the decision-making process.

This was revolutionary. Pan Am copilots actually having an opinion . . .

The other problem was standardization. There wasn't any. Pilots from the unregulated, make-the-rules-as-you-go-along flying boat days were inherently nonstandard. They were, by God, supposed to be different. Flying was a game for individuals-chest-thumping, throttle pushing, flint-eyed Masters of-Ocean-Flying Boats-not compliant drones.

The newer breed of airmen had come from a different environment. High-tech airplanes demanded a collaborative effort from their crews. Uniqueness in a pilot was okay, but it ought to be manifested by excellence, by a mastery of technical skill, rather than by eccentricity.

The magic word standardization brought eventual relief. It meant that everybody operated the airplane the same way. Total strangers captains, first officers, flight engineers-could check in for a flight, enter the cockpit, and work in total harmony. They could fly the airplane around the world-and each would know what the other would do. Gone were the surprises.

It would take time to change an ethic so deeply embedded in the airline's skin, but there was no choice. It had to work.

And it did. The nightmare was over. From 1974, following the Bali crash, not another Pan Am 707 was lost in a crash.

The 747, which was emerging as the new flagship, established itself as the safest airliner ever operated by Pan Am. Not a single life would ever be lost in a flying accident with a Pan Am 747*.

Pan American went on to establish a safety record that was the envy of the industry.

* In neither of two fatal 747 disasters-the bombing of PA 103 in 1988 and the runway collision with a KLM 747 at Tenerife in 1977-was the 747 or the Pan Am crew held to blame.

Source: Gandt, pp. 117-119

2

A few generations

The First Generation of CRM

Right about the time of Pan Am's conversion to the "crew concept," other airlines were having their own problems and it became apparent that even when crews got along, something more was needed. The focus, at least the perceived focus, was on the captain.

In 1972, a Lockheed L-1011 operating as Eastern Airlines Flight 401 flew into the Everglades in Florida as all members of the flight deck crew were focused on a burned-out light bulb. During the troubleshooting, no pilot had been assigned the task of flying the aircraft and, although an altitude discrepancy was noticed by air traffic control, the flight gently descended without the crew noticing the critical controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) problem.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 128-129

For more about this accident, see: Eastern Airlines 401.

[In 1978] A Douglas DC-8 operating as United Airlines Flight 173 crashed near Portland, Oregon, after running out of fuel, killing 10 occupants. The accident resulted from the captain focusing too heavily on preparing the cabin for an emergency landing due to a gear malfunction, while neglecting both the fuel state and the increasing concerns of the other flight crewmembers who were rightfully worried about running out of gas.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 128-129

For more about this accident, see: United Airlines 173.

NASA decided to host a series of conferences in 1979 out of which the CRM concept was officially born. At that time the term stood for Cockpit Resource Management and was narrowly focused on flight deck crewmembers, often comprised of two pilots and a flight engineer in those days.

The first generation of CRM in 1979 focused on changing individual behavior, primarily that of the captain, so that input would be incorporated from other flight deck crewmembers when making decisions.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 128-129

A 1979 NASA study placed 18 airline crews in a Boeing 747 simulator to experience multiple emergencies. The study showed a remarkable amount of variability in the effectiveness with which crews handled the situation. Some crews managed the problems very well, while others committed a large number of operationally serious errors. The primary conclusion drawn from the study was that most problems and errors were introduced by breakdowns in crew coordination rather than by deficits in technical knowledge or skills. The findings were clear: crews who communicated more overall tended to perform better and, in particular, those who exchanged more information about flight status committed fewer errors in the handling of engines and hydraulic and fuel systems and the reading and setting of instruments.

Source: Crew Resource Management (Kanki, Helmreich, Anca), §1.4.4

The Second Generation of CRM

Captains became kinder and gentler, at least comparatively so. First officer still needed a little encouragement to speak up. This was generation two.

Air Florida 90, from AirDisaster.com.

As airline accidents with CRM components continued to happen, such as the very dramatic crash of a Boeing 737 operated as Air Florida flight 90 during a winter storm in Washington, D.C. in 1982, the industry and government continued to cooperate to shape and evolve CRM.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 129-130

For more about this accident, see: Air Florida 90.

As a result of these efforts, around 1984 the second generation of CRM took shape. Instead of changing individual behaviors, CRM now went deeper in an attempt to change attitudes and focus more on decision making as a group.

Special emphasis was placed on briefing strategies and the development of realistic simulator training provides known as Line-Oriented Flight Training (LOFT).

By 1985 only four air carriers in the United States had full CRM programs; United, Continental, Pan Am, and People's Express. American and the U.S. Air Force Military Airlift Command soon introduced CRM programs, and the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps were on the verge of starting CRM programs.

In 1989, a very serious accident happened that provided irrefutable proof that CRM principles worked. A DC-10 operating as United Airlines Flight 232 experienced the uncontained failure of its #2 engine, resulting in a loss of normal flight controls. The captain ably coordinated flight deck and cabin resources to perform a controlled crash of the aircraft at Sioux City, Iowa. The resulting crash killed 111, but there were 185 survivors who likely would have not survived at all had it not been for the CRM prowess of the crew.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 129-130

For more about this accident, see: United Airlines 232.

The United States military and most commercial airline businesses embraced Cockpit Resource Management early and the improvements were dramatic. As more and more of the world embraced CRM, the accident rates fell accordingly. One need only examine the hold outs to fully understand just how far we've come. Examine Korean Airlines for a thirty-seven year look at a country's airlines ignoring the call for CRM, being forced into it, and then working their way around it. It isn't an Asian culture thing. The Japanese realized early on that crashing airplanes and killing passengers was a bad business model.

The Third Generation of CRM

Guess what? There is more to the crew than just the cockpit. In the third attempt, "cockpit" becomes "crew." Okay, that's good. But the academicians start to realize there is an entire new field of study they can corrupt, and things start to go downhill.

Army medicine, from Jim Bryant, NW Guardian, (Creative Commons.)

In the early 1990s the third generation of CRM took hold, which deepened the notion that CRM extended beyond the flight deck door. That generation saw the start of joint training for flight deck and cabin crewmembers, such as for emergency evacuations.

Around 1992 CRM also saw itself being exported to the medical community to address similar group dynamics events associated with medical error in both routine and emergency care at hospitals.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, p. 131

The term non-technical skills (NTS) is used by a range of technical professions (e.g. geoscientists) to describe what they sometimes refer to as "soft" skills. In aviation, the term was first used by the European Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) to refer to CRM skills and was defined as "the cognitive and social skills, of flight crewmembers in the cockpit, not directly related to aircraft control, systems management, and standard operating procedures." They complement workers' technical skills and should reduce errors, increase the capture of errors and help to mitigate when an operational problem occurs.

Source: Crew Resource Management (Kanki, Helmreich, Anca), §6.1

As concern about the rates of adverse events to patients by medical error grew, medical professionals began to look at safety management techniques used in industry. One technique that has attracted their interest is the training and assessment of non-technical skills.

Source: Crew Resource Management (Kanki, Helmreich, Anca), §6.2

Much of the rest of the world, especially that which deals with life and death issues, adopted CRM (or NTS) and have had to do the hard sell to obtain "buy in" from their professionals. Doctors, for example, may reacted just as early airline captains did thirty to forty years ago. Meanwhile, we in the aviation world have seen decades of progress and it is a rare crewmember these days who attempts to push back.

Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, . . . Generations Aplenty

You can recognize the generations of CRM that followed because they tended to involve non-aviation aspects of getting along and often had some kind of other terminology to help confuse things. Around this time I started to lose interest in CRM because it ceased to serve more to confuse than clarify.

- Around the mid-1990s the fourth generation of CRM was introduced, which promoted the FAA's voluntary Advanced Qualification Program (AQP) as a means for "custom tailoring" CRM to the specific needs of each airline and stressed the use of Line Oriented Evaluations (LOEs).

- Around 1999 the fifth generation of CRM took hold, which reframed the safety effort under the umbrella of "error management" modified the initiatives so as to be more readily accepted by non-Western cultures, and placed even more emphasis on automation and, specifically, automation monitoring. Three lines of defense were promoted against error: the avoidance of error in the first place, the trapping of errors that occur so that they are limited in the damage they create, and the mitigation of consequences when errors cannot be trapped.

- At the start of the 21st century, the sixth generation of CRM was formed, which introduced the Threat and Error Management (TEM) framework as a formalized approach for identifying sources of threats and preventing them from impacting safety at the earliest possible time.

- Threats can be any condition that makes a task more complicated, such as rain during ramp operations or fatigue during overnight maintenance. They can be external or internal. External threats are outside the aviation professional's control and could include weather, a late gate change, or not having the correct tool for a job. Internal threats are something that is within the worker's control, such as stress, time pressure, or loss of situational awareness.

- Errors come in the form of noncompliance, procedural, communication, proficiency, or operational decisions.

- To assess the Threat and Error Management aspects of a situation, aviation professionals should:

- Identify threats, errors, and error outcomes.

- Identify "Resolve and Resist" strategies and counter measures already in place.

- Recognize human factors aspects that affect behavior choices and decision making.

- Recommend solutions for changes that lead to a higher level of safety awareness.

Source: Cortés, Cusick, pp. 131-132

3

The problem . . .

. . . is that we in aviation are training crews as if we've made zero progress in the last thirty-plus years. Take a look at the 1990 FAA text and notice there is very little change from what came before and after. They are still teaching this.

The statistical lie about accident rates

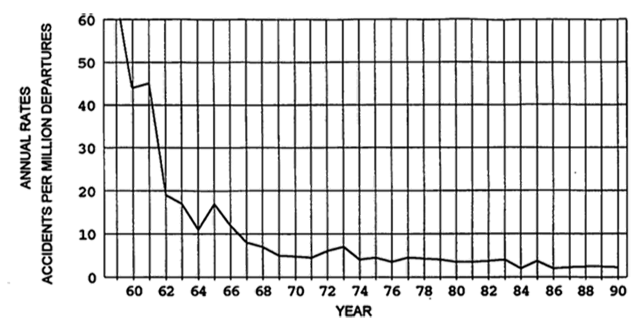

US/Canadian Operators Accident Rates by Year to 1990, from CRM Handbook, figure 1.

From the 1950s to the 1990s we have witnessed a steady decline in aviation accidents. This decline in aviation accidents has been attributed to better equipment, better training, and better operating procedures.

Source: Crew Resource Management: An Introductory Handbook, pg. 1

More about this: Accident Rates.

Notice the chart looks pretty flat from 1986 on.

The statistical lie about accident causes

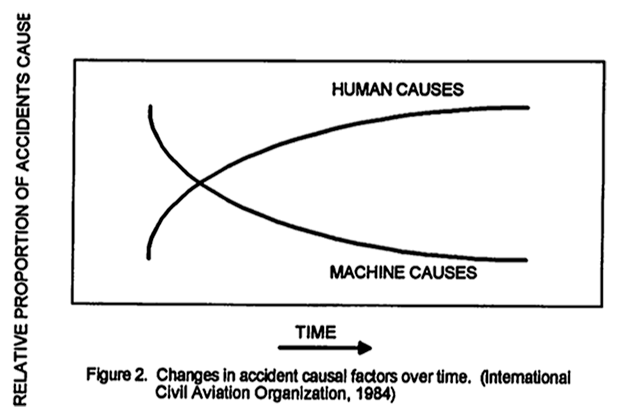

Changes in accident causal factors over time, from CRM Handbook, figure 2.

As Figure 2 illustrates, as accidents related to equipment weaknesses have decreased, accidents attributed to human weaknesses have increased.

Source: Crew Resource Management: An Introductory Handbook, pg. 1

That is what the chart suggests, but it is a lie.

Figure 1 and Figure 2 suggests two points. First, Figure 1 indicates that after a sharp drop in the 1960s, accident rates have leveled off from 1970 through 1990. Second, the trends in causes of accidents illustrated in Figure 2 show that human error has remained a major contributing factor in aviation accidents during these latter years.

Source: Crew Resource Management: An Introductory Handbook, pg. 2

The statistical lies exposed

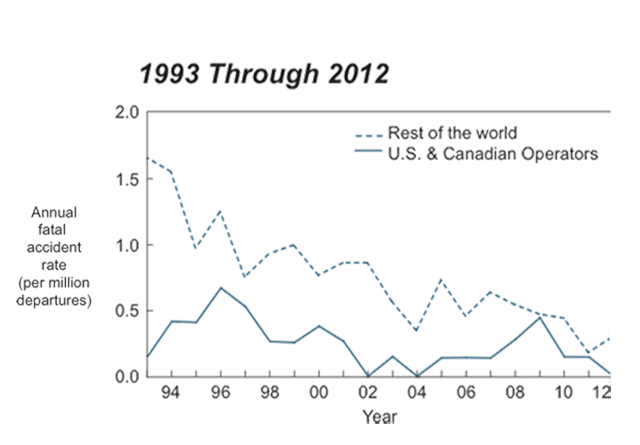

US/Canadian Operators Accident Rates by Year 1993 to 2012, from Boeing Statistical Summary

The first chart seems to show the accident rate has leveled off and we aren't getting any better. This is a distortion caused by the constant scale of the left axis. It is hard to see a trend when the changes are small relative to the scale. If you zoom in you will see the trend continues, as shown by the updated chart here.

The second chart is a lie of improperly used statistics. The chart clearly says "Relative proportion of accidents cause." In plain English:

- The number of accidents has gone down, way down.

- The number of accidents caused by machines has gone down, way down.

- The number of accidents caused by humans has gone down, but not as far down as those cause by machines.

So why is overplaying the problem a problem when it comes to training? Because the problem has changed. The problem in aviation used to be a culture that gave the captain complete authority and discouraged any kind of resistance to that authority. We are over that. While it may be true that not every pilot fully embraces CRM, the vast majority of them say they do. That word, "say," is important here. Because the new problem is that we have a culture that expects all flight crews to embrace CRM and that we have some pilots that may not know how to do that, or are doing that in thoughts only. We have a new problem:

- Some captains think they follow CRM conventions but have never really been tested to see if they "walk the talk."

- Some captains do not embrace CRM conventions, but play act the role in training that does not test their convictions.

- Some captains do not know how to foster a good CRM environment among unfamiliar crews.

- Some captains do not know how to deal with unfamiliar crews that may fall short of the standards set by the crews they are familiar with.

- Some crewmembers do not know how to deal with these captains in a "live" situation, that is, a situation outside the classroom or with captains other than those they are very familiar with.

Notice there is a common factor to all these problems. That leads us to a new training paradigm . . .

4

A possible solution: back to basics

Do you get the idea I liked CRM through the third generation and lost faith in it after that? The CRM fundamentals taught during initial courses are sound and should be understood before moving on to training. Much of what follows comes from the references given below, most mostly these are my thoughts. I've learned CRM from the worst examples as well as the best, so perhaps my experiences will save you the trouble of learning things the hard way. Comments, as usual, are welcome, just hit the contact button above.

- Accomplishes tasks. Besides routine flying duties, the captain’s tasks include directing the activities of members of the crew, establishing priorities, “thinking ahead of the airplane” (anticipating what is yet to come), mentoring the rest of the crew, assuming responsibilities for the crew, and monitoring crew performance.

- Communications. The captain is in many ways the focal point of information in a crew and must regulate the flow of that information to ensure the crew has what it needs and can provide the rest of the crew (including the captain) with what they need. This can be a formalized as required callouts or regulatory forms. It should also include more informal means, such as asking for opinions and feedback.

- Establishing and maintaining a positive environment. A good captain creates the proper climate to encourage good crewmember relations and participation. This climate must maintain positive relations, resolve and prevent conflict, and encourage critique and feedback. A positive environment encourages good situational awareness and avoids “tunnel vision” or “target fixation.”

- Make decisions. The captain’s decision-making process must begin with gathering and evaluating information and end with assuming responsibility for those decisions. Along the way the captain must encourage a monitoring – feedback – and adjustment loop, as time permits.

- Potential pitfalls. The captain may be tempted to retreat into the familiar – flying the airplane – at the expense of taking command of the unfamiliar. The captain may convince him or herself that flying the airplane is the most important task and that relieves them of the burden of confronting the unknowns in a situation. Captains can also be convinced they are crew resource management gurus because they never receive (or listen to) any evidence to the contrary. This only worsens the negative CRM behavior.

Captain Clarence Over, First Officer Roger Murdock, and Second Officer Victor Vostock, from the movie "Airplane."

- Accomplishes tasks. Each crewmember has specific tasks to accomplish that often require coordination with other members of the crew. Their tasks may also include additional duties assigned by others which should be accepted, if possible. If not possible, the issue needs to be elevated as necessary so the task is not neglected.

- Communications. Each member of the crew is responsible for the two-way direction of crew communications; they must not only receive but also transmit. An important facet of this exchange of information is that the message must not only be sent or receive, it must be understood. Members of the crew are responsible for providing opinions and feedback.

- Establishing and maintaining a positive environment. Every member of the crew shares the captain’s responsibility to create the proper climate to encourage good crewmember relations and participation. Interpersonal grudges and other “baggage” must be compartmentalized and left outside the flight environment.

- Make decisions. While all crewmembers have individual decision-making responsibilities, they must recognize the captain’s decision-making process is the most consequential and requires active monitoring and feedback. Disagreements are to be expected and should be handled by an inquiry / advocacy / assertion process (discussed below).

- Potential pitfalls. Falling prey to complacency is a risk for every member of the crew but the captain has the added responsibility of the crew’s conduct and presumably has the additional experience of understanding the pitfall of succumbing to complacency. Other members of the crew are at increased risk because they have less to “worry about” and may feel they have mastered the job before the hard experience of realizing the job can never be mastered.

5

Another solution: learn from successful crews

I spent a fair amount of time on dysfunctional cockpit crews. I also got a jumpseat view of a few more as an instructor and examiner pilot. But I've been fortunate in that for most of my career, most of the crews I've flown with seemed to have "gotten it." The "it" was how to work together as a team before, during, and after moments when things didn't go as planned. So here are the traits I've notice on all successful crews.

The decision-making process

Many books on the subject will talk about a process, from start to finish, when making decisions. In aviation, where time is a factor, it may be helpful to think of decision-making in the form of a cycle. The following steps are repeated as necessary and as time permits.

- Identify the issue that requires action.

- Collect information.

- Solicit input from within and outside the crew.

- Identify and evaluate possible solutions, including crewmember inputs.

- Implement the decision.

- Review the consequences, adjust as necessary.

- Repeat the process, as necessary.

Inquiry / Advocacy / Assertion

Inquiry.

In a healthy CRM environment, questions are encouraged and answered openly and nondefensively.

[CRM Leadership & Followership 2.0, Antonio Cortés] Show Respect for Fellow Crewmembers. Showing respect to the other members of the crew, naturally including the captain, is not just a matter of courtesy, it is fundamental to fostering a sense of shared purpose that is the building block for teamwork. One of the most important ways of showing respect is by listening to others. This means actively listening for content in what another crewmember is saying, not just "hearing" what is being said.

Advocacy.

In a healthy CRM environment, crewmembers are encouraged to speak up and state opinions with appropriate persistence until there is a clear resolution. This can be encouraged by captains who ask the right questions. "Do you have anything to add?" prompts a yes/no answer and a "no" can appear to the timid crewmember to be a threat to the captain's authority. "What am I forgetting?" will be seen as a request for help and encourages input.

Assertion.

In a healthy CRM environment, crewmembers are allowed to question the actions and decisions of others and to seek help from others when necessary. Of course, the final arbiter is the captain, who must weigh all concerns before deciding. An important point is that the captain must err on the side of safety, so that a crewmember’s concern that may or may not be valid, in the captain’s view, may carry the day if the action lowers potential risk.

[CRM Leadership & Followership 2.0, Antonio Cortés] Regardless of what tone has been set by the captain, crewmembers have an obligation to be assertive and to voice concerns and opinions on matters of importance to the safety of the flight.

Crewmembers must understand that there are few things more corrosive to a crew’s integrity than to have a crewmember disagree with the captain in front of the rest of the crew or passengers. A good way to show respect for good crew resource management is to disagree with other crewmembers (including the captain) in private, if time permits.

If the captain is not listening or doesn’t grasp the gravity of a situation, the following techniques may prove useful:

- Get the captain's attention (use name or crew position/opposite typical): "Jim, I have a concern I want to discuss with you."

- State the concern: "I am not comfortable with this heading that we are on."

- State the problem and consequences: "If we continue on this heading, we will be too close to the buildup."

- Give solutions: "I think we should turn 20 degrees further west."

- Solicit feedback and seek agreement: "What do you think?" or "Don't you think so?"

6

How to avoid the "Master of Ocean Flying Boats" trap

It is all too tempting to take a look at the Pan American World Airways Boeing 707 era and say, "that's ancient history." It predates the 1979 NASA study which is supposed to have given birth the Crew Resource Management (CRM), after all! But here we are, almost forty years later, and we can still see old vestiges of the those crusty old Pan Am Captains — the ones the CEO called "Master of Ocean Flying Boats" — in cockpits today, as well as the occasional first officer too afraid to speak up.

So there are lessons aplenty. First, lessons on how to avoid falling into the culture that gave rise to these problems in the first place. And, secondly, lessons on how to fix those who have somehow become broken.

Of course these are just my thoughts. Am I wrong? Or can these be improved upon? Hit the "contact" button on the bottom or top if this page, and let me know.

- An honest captain is honest about his or her own shortcomings — Nobody (not even you) can fly without making mistakes. We often excuse these mistakes on mechanical failures, misunderstandings, weather, or even acts of God. But for most of these, we must realize there could have been something we could have done to do better. The best way to learn is to seek critique from formal means (check rides, observations, and audits), from the crew ("how could we have done better?" debriefs), and from self-critiques ("how could I have done better?").

- A strong captain wants a strong crew, a weak captain wants a weak crew; both types get what they want — A crew that fears retribution (everything from a "cold shoulder" to a formal and written rebuke) may be reluctant to act as a crew and may even start to disengage from their roles as active participants of the crew. If, for example, a first officer is reprimanded for making glide slope deviation callout, the first officer may stop paying attention to the glide slope needle.

- Organizations can promote strong crews by preventing organizational complacency — Pan American World Airways started the jet age with a well deserved reputation for being the best international airline in the world. They invented the entire genre. But one of the problems with a large group of pilots beholden to the seniority system is the higher up the food chain you are, the more comfortable you become. This comfort breeds complacency. But even a very small flight department can give into the same forces. If you are one of two pilots doing the same job without outside oversight for years and years, you are at risk. So how do you introduce a little humility? Don't let anyone get comfortable. Here are some techniques:

- Buying a new airplane can force everyone to become experts at new things, but only if you structure it correctly. Rather than hand them the keys to the new bird with an airline ticket to school, get them involved in the selection process. Give them a say on who does the training, and make some of that training in house. (The best way to learn is to teach.)

- Take some (or all) management duties in house. A bored pilot who has never had to apply for an FAA Letter of Authorization has a lot to learn about the FAA as well as the specific authorization. Your pilots will have a better appreciation for RVSM, for example, after having to get the LOA.

- Shuffle job responsibilities. If you have a "go to" guy in your flight department that you keep going to, because you want things done right, you are stunting the career development potential of your second stringers. In the end, everyone gets bored.

- Introduce new blood. Find another flight department with similar equipment and offer an inter-fly agreement to help out to cover the load when manning is short. Once you've done this, try to "cross pollinate" your safety and standards departments.

Recognizing a "Master of Ocean Flying Boats"

We in aviation are not alone with these Masters of Flying Boats. Perhaps the best way to learn how to spot one is to examine one in another profession. Here's a report from Surgeon Atul Gawande:

The most common obstacle to effective teams, it turns out, is not the occasional fire-breathing, scalpel-flinging, terror-inducing surgeon, though some do exist. (One favorite example: Several years ago, when I was in training, a senior surgeon grew incensed with one of my fellow residents for questioning the operative plan and commanded him to leave the table and stand in the corner until he was sorry. When he refused, the surgeon threw him out of the room and tried to get him suspended for insubordination.) No, the more familiar and widely dangerous issue is a kind of silent disengagement, the consequence of specialized technicians sticking narrowly to their domains. "That's not my problem" is possibly the worst thing people can think, whether they are starting an operation, taxiing an airplane full of passengers down a runway, or building a thousand-foot-tall skyscraper. But in medicine, we see it all the time.

Source: Gawande, p. 103

How to turn a "Master of Ocean Flying Boats" into a real Crewmember

- Safety Stand Downs — The best way to show a "Master of Ocean Flying Boats" that he or she isn't so special is to put him or her in an auditorium filled with other pilots who have longer resumes, flown more airplanes, and have higher "Master of . . ." credentials but are humble enough to worry about their own complacency. But if you are going to send your prima donna to an all expenses paid trip, ask for something in return. Look at the agenda and ask for a detailed report about the subjects you think more important.

- Personal Case Studies — The next time the industry has a high profile crash, ask your "Master of . . ." to investigate and give you his or her perspective. Ask for follow ups as the official investigation unfolds. There is nothing more humbling than to get into the weeds about a crash and realize, "it could happen to me."

- Hire an intern — Ask your "Master of . . ." to mentor a younger pilot that you know or can find through local flight schools. Let him or her know this is important to you. You want to "give back" and this is one way to do that. Having to show an outsider what goes on behind the curtain may force the "Master of . . ." to rethink the reason there is a curtain there in the first place.

7

Case studies

- Air Blue ABQ-202 (2010) — The airplane crashed and killed everyone on board because of the captain's poor airmanship while flying the airplane into a mountain. But on the way to the scene of the accident he beat the first officer down to the point the right seat was occupied by a passenger, unwilling to speak up.

- Air Florida 90 (1982) — An amiable captain with inadequate experience dealing with icing conditions was paired with a first officer who had the right answer but unwilling to speak forcefully. Most everyone on board was killed.

- Air Illinois 710 (1983) — A captain with an internal drive to keep the schedule and a reputation of getting angry with first officers with other view points decided to press on to his destination after an electrical failure. His destination was IFR, over 30 minutes away. He could have turned back to his departure airport, which was VFR. All aboard were killed.

- Allegheny Airlines 453 (1978) — A complete lack of discipline in the cockpit is evidence by sloppy procedures, the absence of required callouts, and stabilized approach monitoring. The lack of crew resource management destroyed the airplane.

- Eastern Airlines 401 (1972) — The pilots failed to continuously monitor the airplane while troubleshooting a gear position light and allowed the airplane to descend into the Everglades, killing all on board.

- Galaxy Airlines 201 (1985) — A breakdown in crew coordination following an unexpected vibration shortly after takeoff led to loss of control of the airplane and all but one person on board.

- Japan Air Lines 8054 (1977) — The crew was unwilling to confront an intoxicated captain who over-rotated into a stall, losing control of the aircraft and killing all on board.

- United Airlines 173 (1978) — A captain not listening to the crew and a crew not being forceful enough caused the loss of an airplane and many lives.

- United Airlines 232 (1989) — The mishap was caused by shortsighted aircraft certification rules that led to an engine failure that took out all the airplane's hydraulic systems. Excellent CRM saved many lives that day.

- A Haskel CRM story: B-707 Depressurization — Just a short story about how I learned a captain must sometimes command as opposed to lead.

8

CRM contract: "I agree not to kill you"

N605TR flight path,

NTSB Preliminary Report WPR21FA286

I thought there was a tacit contract among all professional aircrews that can be summed up briefly as, “I agree not to kill you.” Expanded, this contract reads:

“I agree that during the approach and landing phase, we will err on the side of caution and if either pilot becomes uncomfortable to the point of calling for a go around, the other pilot will immediately go around. We will discuss the reasons for the go around after we safely land. The only exception can be if fuel or other conditions make a second approach impossible. Further, if the call for a go around proves unnecessary, there will be no hard feelings, we will learn from the event and press on.”

I say I thought that this contract tacit – that is to say “understood” without having to be said before hand – but now I am not so sure. Consider the final turn loss of control of a Challenger 605 at Truckee Airport, California (KTRK), July 26, 2021. The Pilot In Command (PIC) was also the Pilot Flying (PF) and had 235 hours in Challengers, most of that in the older Challenger 601. The Second In Command (SIC) was the Pilot Monitoring (PM), was a contract pilot, and was highly experienced with well over 4,000 hours in Challengers. The PF shot the KTRK RNAV (GPS) 20, attempted to circle to Runway 11 and lost control of the aircraft. While much of the focus has been on the weather, which was adequate, and the fact the aircraft was maneuvered too close to the landing runway to successfully circle, all of that misses the critical point. To really understand the tragedy of this accident, one need only read the last sixty seconds of the transcript of the Cockpit Voice Recorder:

13:17:12.6 (PM) we don't wanna be on the news.

13:17:14.8 (PM) autothrottles have it.

13:17:17.8 (PM) you are looking very good my friend.

13:17:24.1 (PM) nice and relaxed...bring that turn around.

13:17:24.3 (Cockpit Mike) sound similar to increase in engine rpm

13:17:27.5 (PM) perfect.

13:17:30.2 (PM) it's okay...you got plenty of time.

13:17:33.6 (PM) let it keep comin' down though.

13:17:41.4 (Cockpit Mike) one thousand. [electronic voice]

13:17:42.7 (PM) did you? oh you turned the throttles off...

13:17:43.5 (Cockpit Mike) [sound similar to altitude alert]

13:17:44.4 (PF) yes.

13:17:44.6 (PM) shoot (expletive)

13:17:46.4 (PM) let me see the airplane for a second.

13:17:51.6 (Cockpit Mike) sound similar to decreasing engine rpm

13:17:54.7 (PM) we're gonna go through it and come back okay?

13:17:56.8 (PF) okayyy . . .

13:18:00.4 (PF) It's here. [exclamation]

13:18:01.4 (PM) yes yes it's here but we are very high.

13:18:03.6 (Cockpit Mike) sink rate. [electronic voice]

13:18:04.2 (Cockpit Mike) sounds similar to stick shaker activation

13:18:04.2 (PF) what are you doing?

13:18:04.2 (Cockpit Mike) pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:04.5 (PM) ‘kay.

13:18:04.8 (PF) (unintelligible word)

13:18:04.9 (Cockpit Mike) warbler sound consistent with stall warning

13:18:05.0 (PM) no no no.

13:18:06.2 (PM) let-

13:18:06.5 (PF) what are you doing?

13:18:06.6 (Cockpit Mike) pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:06.6 (PM) let me have the airplane.

13:18:07.3 (PM) let me have the airplane.

13:18:07.9 (Cockpit Mike) sounds similar to stick shaker activation

13:18:07.9 (Cockpit Mike) warbler sound consistent with stall warning, continues throughout the end of the recording

13:18:08.0 (Cockpit Mike) pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:08.6 (PM) let me have the airplane.

13:18:09.4 (Cockpit Mike) pull up. [electronic voice]

13:18:09.7 (PF) oh. [exclamation]

13:18:10.0 (PM) oh (expletive)

13:18:10.8 (PF or PM) (expletive)

13:18:11.0 (Cockpit Mike) pull-- [electronic voice]

13:18:11.3 (Cockpit Mike) (sounds consistent with impact)

13:18:12.2 End of recording

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation continues but the accident docket already has a lot of important information, including the CVR transcript. If you’ve never explored an accident docket before, this one will be a valuable, however sobering, introduction. Go to www.ntsb.gov, select Investigations, Investigations Dockets, and enter the search criteria. You could enter the accident date and other particulars, but in this case, you can simply type in the NTSB Accident ID Number, WPR21FA286. As the investigation continues the docket will grow, but as of this writing there are 35 items.

This accident docket not only makes for a great CRM case study, it provides several lessons about aerodynamics and aircraft stall characteristics. If you are a Challenger pilot, you will learn more about your aircraft’s low speed flying characteristics than you’ve ever learned during initial or recurrent training.

It will be natural for most pilots to say they wouldn’t have put their aircraft into a final turn stall or they would have been more assertive making a go around call. As to the first point, we all suffer from the “I can save this” philosophy because we have done just that so many times. This brand new 605 pilot may not have understood that the Challenger series of aircraft do not react well to being loaded up in a turn and usually stall asymmetrically. (In this case, the low wing dropped abruptly past 140° just prior to ground impact.) Both pilots probably didn’t realize the aircraft’s weight and balance was out of date and 3,000 lbs. below actual weight, causing them to calculate their reference speed 6 knots too low. At some point the aircraft’s spoilers were deployed, reducing the stall angle of attack. Both pilots were either unaware of this effect or too task saturated to realize the boards were deployed.

Needless to say, both pilots made several errors on their way to crashing and I predict the NTSB will find both as causal. But a final note to contract pilots is in order. Being “guest help” on an aircraft requires tact and the ability to communicate in a way that gets your point across without jeopardizing future employment. But you must never allow the other pilot to exceed your limits. I was alarmed by the PM’s “let me have the airplane” request. My time as a contract pilot is limited, probably because of the one time I’ve been in a similar situation. My statement was not nearly so diplomatic: “Go around.” When the pilot didn’t respond I said, “Go around now or I’m taking the aircraft and we will go around.” He finally complied.

References

(Source material)

Advisory Circular 120-51E, Crew Resource Management Training, 1/22/04, U.S. Department of Transportation

Aircraft Accident Report 4/90, Department of Transport, Air Accidents Investigation Branch, Royal Aerospace Establishment, Report on the accident to Boeing 737-400 G-OBME near Kegworth, Leicestershire on 8 January 1989

Boeing Commercial Airplanes, Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents, Worldwide Operations 1959 - 2012, 2013

Cortés, Antonio; Cusick, Stephen; Rodrigues, Clarence, Commercial Aviation Safety, McGraw Hill Education, New York, NY, 2017.

Cortés, Antonio, CRM Leadership & Followership 2.0, ERAU Department of Aeronautical Science, 2008

Crew Resource Management: An Introductory Handbook, DOT/FAA/RD-92/26, DOT-VNTSC-FAA-92-8, Research and Development Service, Washington, DC, August 1992

Dekker, Sidney and Lundström, Johan, From Threat and Error Management (TEM) to Resilience, Journal of Human Factors and Aerospace Safety, May 2007

Fallucco, Sal J., Aircraft Command Techniques, 2002, Ashgate, Farnham, England

Flight Safety Foundation, Aviation Safety World, "Pressing the Approach," December 2006

Gann, Ernest K., Fate is the Hunter: A Pilot's Memoir, 1961, Simon & Schuster, New York

Gandt, Robert, Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am, 2012, Wm. Morrow Company, Inc., New York

Gawande, Atul., The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, 2009, Metropolitan Boos, Henry Holt and Company, LLC, New York.

Helmreich, Robert L., Klinect, James R., Wilhem, John A., Models of Threat, Error, and CRM in Flight Operations, University of Texas

Kanki, Barbara; Helmreich, Robert; and Anca, José, Crew Resource Management, Academic Press, Amsterdam, 2010.

Lutat, Christopher J. and Swah, S. Ryan, Automation Airmanship, McGraw Hill Education, London, 2013.

NTSB Preliminary Report WPR21FA286, Bombardier Inc CL-600-2B16, Truckee, CA, July 26, 2021.

Portugal Accident Investigation Final Report, All Engines-out Landing Due to Fuel Exhaustion, Air Transat, Airbus A330-243 marks C-GITS, Lajes, Azores, Portugal, 24 August 2001