The motto of the 89th Airlift Wing: “Experto Crede,” trust one with experience. This is the story of my last flight as a Special Air Missions (SAM) pilot for the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base, near Washington, D.C. While we pilots were not prone to talking in Latin, the wing’s motto weighed heavily on us because we trained to a very high standard.

— James Albright

In nearly forty years as a pilot, I must say some of the finest pilots I’ve ever known wore the “Special Air Missions” jacket of the 89th. I was flying with one of the good ones in the story that follows. This story also appears as the opening to Flight Lessons 3: Experience, where we widen our gaze to cover some of those that aren't up to the standard we would expect from the 89th. I later learned I was at the 89th during a rare time in its history, a transition period of sorts. It is a story worth telling because the lessons along the way reinforce lessons learned the hard way, sometimes decades before. Each chapter concludes with the relevant case study and my notes.

Everything in Flight Lessons 3: Experience really happened. I’ve changed the order here and there and combined a few characters to protect an identity or two. But back to this, my last flight as a SAM pilot . . .

Updated:

2015-12-13

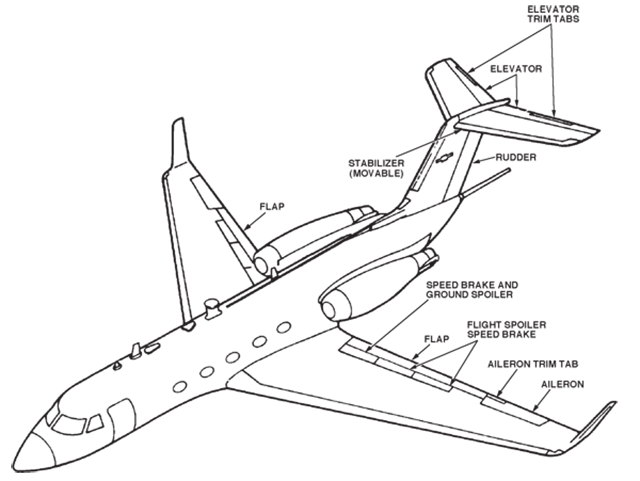

“Nutcracker fail,” I heard from the right seat. I looked down, just forward of the throttles and my right knee. His left index finger was on the test switch, which showed our left system was green and the right system was not. The Gulfstream III employs a series of switches on each landing gear to determine if the airplane is inflight or on the ground. The switches employed on the main landing gear legs were mounted on two arms that formed a scissor, but to the designer’s eye looked more like a nutcracker. All three switches had a vote, but the two nutcrackers on the main landing gear had the biggest votes. The airplane had three panels on each wing, known as spoilers, which would deploy once the airplane landed. By spoiling the lift of the wing, the airplane was better able to stop. If this were to happen in flight, of course, that would be a problem. So we had to test the nutcracker system prior to every landing once the landing gear was extended. The first Gulfstream jet ever lost, a GII, crashed in 1974 because of a malfunction of this very system.

“Pull the ground spoiler circuit breaker, behind me, row C, column 9,” I said. “After you get that, run the nutcracker fail checklist.” Hank unbuckled his lap belt and reached cross-cockpit behind my head to pull the circuit breaker, ending the threat of our Gulfstream’s ground spoilers inadvertently deploying and throwing our airplane out of the sky prematurely. I knew he had the checklist memorized and that our squadron expected us to run it by memory, but we both knew this was life and death. The checklist exists for a reason.

“Ground spoilers off,” he began and then rattled off the rest of the checklist. “If the nutcracker stays in the air mode you aren’t going to have any nose wheel steering, no anti-skid braking, and the landing gear safety solenoid is gone.”

Good points all, I thought. I watched as the glide slope pointer centered, double checked the disabled ground spoiler switch, and pulled the throttles back a full knob-width. “Full flaps,” I said. “Well, we’ve got all eleven thousand feet of runway, but only the middle thirty feet is plowed. The braking action is fair and we’ve got a ten-knot direct crosswind. We are worried about an inadvertent ground spoiler deployment when the throttles hit idle. We are worried about directional control on a snow-covered runway with a crosswind because we don’t have nosewheel steering. We are worried about the braking without anti-skid. We’re worried about the gear collapsing if we hit too hard. Is there anything else we are worried about?”

“That’s plenty,” Hank said.

“Do we have any other options?” I asked, knowing the answer.

“Nope.” The forecast was for snow and nothing more. Sometime between our takeoff from Cincinnati and our arrival the entire east coast was shellacked in snow, sleet, and then more snow. Andrews Air Force Base stayed open throughout, managing to keep a narrow strip of runway open for its aircraft arriving from all over the world. We were the last of ten arrivals for the night. Meanwhile, just as we began our descent, the civilian airports were closing, one-by-one. Just as we began our instrument approach the last one, Washington National, threw in the towel.

“You got enough fuel for three tries,” the flight engineer reported, “but not enough to go anywhere else.”

“Before landing checklist is complete,” Hank reported finally. “I’m glad I get to watch this.”

“I’m going to put the airplane down gently right on the numbers,” I said. “Engineer will get the speed brakes. I will go to idle reverse on the engines, but no more. We’ll get a feel for directional control and I’ll try to do that with ailerons and rudder only until I can’t. Then I’ll go for the brakes. The airplane is going to weather vane left. If it looks like I am losing it, Hank, take the engines from me and use right reverser to keep us on centerline.”

“You got it.”

“Charlie,” I said over the interphone to the flight engineer, “we haven’t briefed anyone else. If I say the word, you take charge of everything aft and get the passengers out of the airplane, off the runway, and keep them together. How many we got?”

“Eight pax and five crew, sir,” he said. “I’ll take care of everything behind the cockpit.”

“Passing a thousand,” Hank said. The altimeter slowly unwound and I watched as the vertical velocity needle settled on 600 feet per minute, right where I wanted it. The needles were centered and our ground speed was right at 120 knots. I had a decision to make at 100 feet above the runway, this being a Category II instrument landing system approach. The math always came easy to me. My decision would be made in 900 feet altitude, which would be 900 divided by 600, which equals 1 and a half minutes or 90 seconds. Ten seconds later we would be on the ground.

“A needle width right,” Hank said. The math was easy, but keeping the needles centered in the crosswind made things hard. The autopilot wasn’t dealing with all the variables as well as the engineers who designed it had hoped. My left thumb moved a half-inch to the red disconnect switch and fired the autopilot from its appointed duty. I dipped the left wing into and out of a gentle bank.

“Everything’s centered James,” Hank said. “Five hundred feet and I don’t see anything.”

Decision in 400 feet; just hold on for another 40 seconds, I told myself.

“Winds 270 at 10,” tower offered, perhaps trying to help in the last half-minute left. “Ceiling is right at 100 feet and visibility is a half. Braking action fair, reported by a vehicle. Reminder, only the middle 30 feet is plowed.”

“One hundred above,” Hanks said, “still nothing.”

That would be ten seconds, I thought. The smallest needle on the altimeter continued its relentless move south.

“Lights!” he said.

I looked up and saw two white lights, then a row of lights, and then the runway. It was still snowing but the runway centerline lights shone through a few inches of powder. There was clearly a path of less snow in the middle but the texture to either side was all-wrong. A foot of snow, maybe. I set the left wheels down first, then the right, and the nosewheel came down on centerline. I felt Charlie’s hand slide under my right arm to grab the speed brake handle. I pulled up on the reversers to their locks, waiting to hear the familiar click-click of the locks release, telling me I had thrust reversers at my disposal. I kept them at idle, not wanting to complicate the directional control problem to come or to obscure my vision from the snow kicking forward. I could see no more than a quarter of the runway.

“One-hundred-twenty,” Hank said, “good reverse.” I felt the reassuring thumpa-thumpa of the nosewheel hitting the recessed centerline lights of the runway.

“I’m moving five feet to the right,” I said, “give me some room when we lose rudder effectiveness.”

“Good idea,” Hank said. The main landing gear were 14 feet apart. We had a lane of 30 feet. On centerline the wheels were 8 feet from the snow, moving right 5 feet gave me 3 feet of cushion. The math comes easy. My right leg was slowly extending, coaxing the rudder to the right, which aerodynamically pushed the tail left and kept the airplane going straight despite the wind.

“One-ten,” Hank said, “VMCA in ten.” Our minimum control velocity, VMCA, with aerodynamic controls only was 100 knots. Below that point we couldn’t guarantee aircraft control without ground controls. That was normally the nosewheel steering but that wasn’t an option for us. I had to keep in the lane of cleared runway. Having either main landing gear hit the wall of snow would cause it to dig in, pull the airplane violently to that side. At this speed we would cartwheel for sure. My eyes were right over runway centerline, so the airplane was about 5 feet right. The math . . .

“One-hundred,” Hank said, “starting to move left.” My right leg reached the limit of the rudder, there was nothing left. Left. That is the direction the nose started to move. I willed my tibialis anterior muscles in my lower right leg to extend and the figularis longus to contract, helping push the top of my right foot to extend and actuate, lightly, the brakes on the right landing gear. Thumpa-thumpa.

“Ninety,” Hank said, “on centerline.”

“You got half the runway behind you,” Charlie said.

The brakes would have started all this at ambient temperature, around -5° centigrade. As the friction between each moving disc and each stationary rotor increased, they would heat up and become more effective. Too much pressure and they would lock up without the antiskid. A locked brake turned the tire into an ice skate. Hold what you got, I thought.

“Moving left,” Hank said. No more thumpa-thumpa.

The crosswind! The rudder was becoming less effective at keeping us pointed down the runway but the vertical fin was becoming more effective as a weather vane, trying to point us off the runway. More flex on the tibialis anterior, more pressure on the top of my right foot. “Correcting,” I said.

“Eighty,” Hank said, “almost on centerline.” My right leg started to throb from the pressure and I wondered if I had all the pressure the right brakes would take. The limit was 600 psi on a dry surface but this wasn’t dry. I pressed harder but the nose resumed its drift to the left. I lifted the right reverser handle and pulled up, guessing a few inches would be enough.

“Sixty,” Hank said, “starting to run out of runway.”

“Three-thousand left,” Charlie said.

In the Boeing 747 we would double the distance remaining and multiply that by ten to compute an on-target braking. Sixty knots was perfect for a dry runway and normal brakes. The math came easy. We didn’t have a dry runway or normal brakes. I started to flex my left leg muscles and add more right reverse. Thumpa-thumpa.

“Forty,” Hank said. “Thirty, twenty, ten.” I felt the nose bob unceremoniously as we came to a stop. The two landing lights cast their oblong shapes, equidistant either side of the runway centerline lights. The snow, blowing from left to right, obscured the end of the runway, perhaps a thousand feet ahead of us. I knew the Secretary of State, seated thirty feet behind me, might be unhappy with the drama of our arrival and I might have some explaining to do. But we were stopped.

“Experto Crede,” Hank said.

“Indeed.”