When I was a TAG Aviation check airman we had a pretty good record of fighting FAA certificate actions, until the last one. (They tore down the entire company with that one and TAG USA is no more.) In that time I learned a few things and after listening to lawyers on both sides I have come to several conclusions.

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-09-23

Update: things have gotten much better since I wrote this in 2015. Make sure you see When Tower Asks You to Call next.

1 — Pilot readbacks of a clearance do not guarantee you immunity

2 — You aren't being paranoid, they really are out to get you

3 — The controller's hands are tied, you can be busted without them knowing it

4 — The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) is more and less than you think it is

5 — Get your testimony on paper, officially (as soon as possible)

6 — When the Fed calls, what you say can and will be taken out of context and used against you

7 — An aviation attorney may become necessary; it is your livelihood after all

1

Pilot readbacks of a clearance do not guarantee you immunity

Imagine you have departed the busy Los Angeles area on an IFR flight plan with a clearance to 17,000 feet. You fully expect to get the next clearance before reaching 17,000 feet.

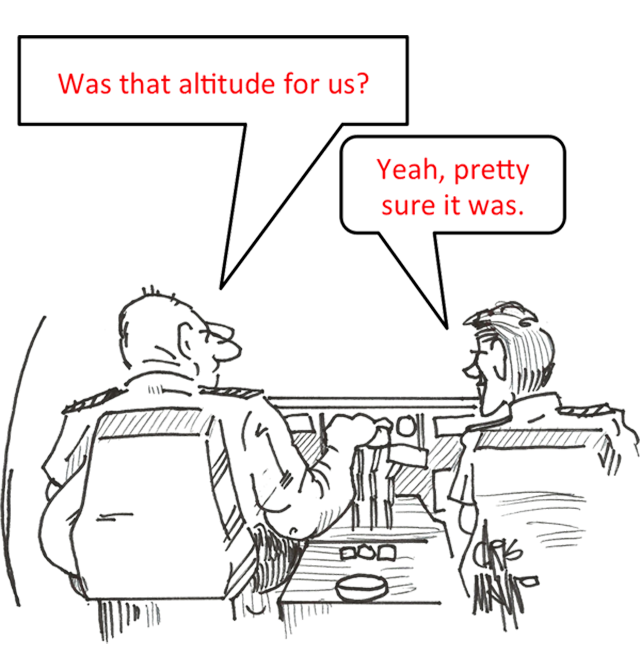

ATC: “Climb and maintain flight level two three zero.”

You: “Roger, climb to flight level two three zero.”

Passing 18,200 feet you hear this:

ATC: “Say altitude?”

This scenario happened on June 19, 1994 to Northwest Airlines Captain Richard Merrell. The clearance to FL 230 was intended for another pilot, who read back the clearance at precisely the same time. Air traffic control never heard Merrell’s read back and did not correct his error.

The FAA issued an enforcement order against Captain Merrell. The order alleged that Merrell had violated FAA safety regulations by operating an aircraft contrary to an ATC instruction in an area in which air traffic control is exercised, in violation of 14 C.F.R. § 91.123(b).

Merrell appealed the enforcement order. After listening to the tape he conceded that he had simply “misheard” the instruction but argued that ATC controllers are required to correct erroneous read backs. The NTSB accepted his arguments and dismissed the enforcement order, saying there was “no evidence in the record that [he] was performing his duties in a careless or otherwise unprofessional manner.”

The FAA argued that the Board's decision would have a “profound” negative effect on air safety: “Under the decision, airmen can claim, without further proof, that they did not hear or that they misperceived safety crucial instructions as a means to avoid responsibility for noncompliance or erroneous compliance with ATC clearances and instructions.”

NTSB Order No. EA-4814 reversed the board’s earlier dismissal. “Under the Administrator’s interpretation of the relevant regulations, however, an error of perception does not constitute a reasonable explanation for a deviation from a clearly transmitted clearance or instruction. Rather, inattentiveness or carelessness is presumed from the occurrence of a deviation unless, as we understand it, the misperception or mistake concerning the clearance was attributable to some factor for which the airman was not responsible, such as an equipment failure.”

Source: Extracted from US Court of Appeals, No. 98-1365.

Carelessness is presumed.

The FAA is given free reign in these cases unless the pilot can prove there was a factor beyond his or her control. The pilot can be forgiven for thinking he or she is guilty until proven innocent in these cases. So how does the pilot keep this from happening in the first place?

- Hear the transmission clearly. Wearing a headset helps, wearing a noise reduction headset helps a lot. Best practices dictate you receive every clearance using a headset and to never rely on cockpit speakers.

- Read back, clearly and in the order the controller expects it. The Aeronautical Information Manual, paragraph 4-4-7, recommends you begin your read back with your call sign and then the clearance exactly as it was given to you. Few pilots start their transmissions with their call signs, reasoning that the sooner they spit out the clearance the better the odds they will remember it. But starting the transmission with your call sign prepares the controller to listen. If you read back the clearance in the exact order given, the controller will be more apt to detect any errors.

- Never say “to” or “for” in an altitude clearance. Common practice is to read back an altitude clearance while still climbing or descending using the words “to” or “for.” For example, “Tiger 66 is passing 6,000 feet for 3,000 feet.” In 1989, Flying Tiger Flight 66 was told to descend “two four zero zero” (2,400 feet) but the pilot heard “to four zero zero” (400 feet). The aircraft crashed and all aboard were killed.

- A better technique is to avoid “to” and “for” in any altitude clearance by using the words “climbing,” “descending,” and “passing” instead. Our example read back becomes: “Tiger 66 passing 6,000 feet descending 3,000 feet.”

- Avoid jargon. You may understand “angels,” “tally ho,” “bogey,” or even “fish finder.” But the controller might not. They gave you and the controller a perfectly good pilot/controller glossary for a reason. (You should read it.)

More about this: Flying Tiger Line 66.

Note: this does run contrary to AIM 5-3-1 (b) which still uses "to" and "for" in recommended readbacks. But in my opinion, the technique is so much stronger, safer, and efficient than the procedure, that you are well justified to adopting it.

2

You aren't being paranoid, they really are out to get you

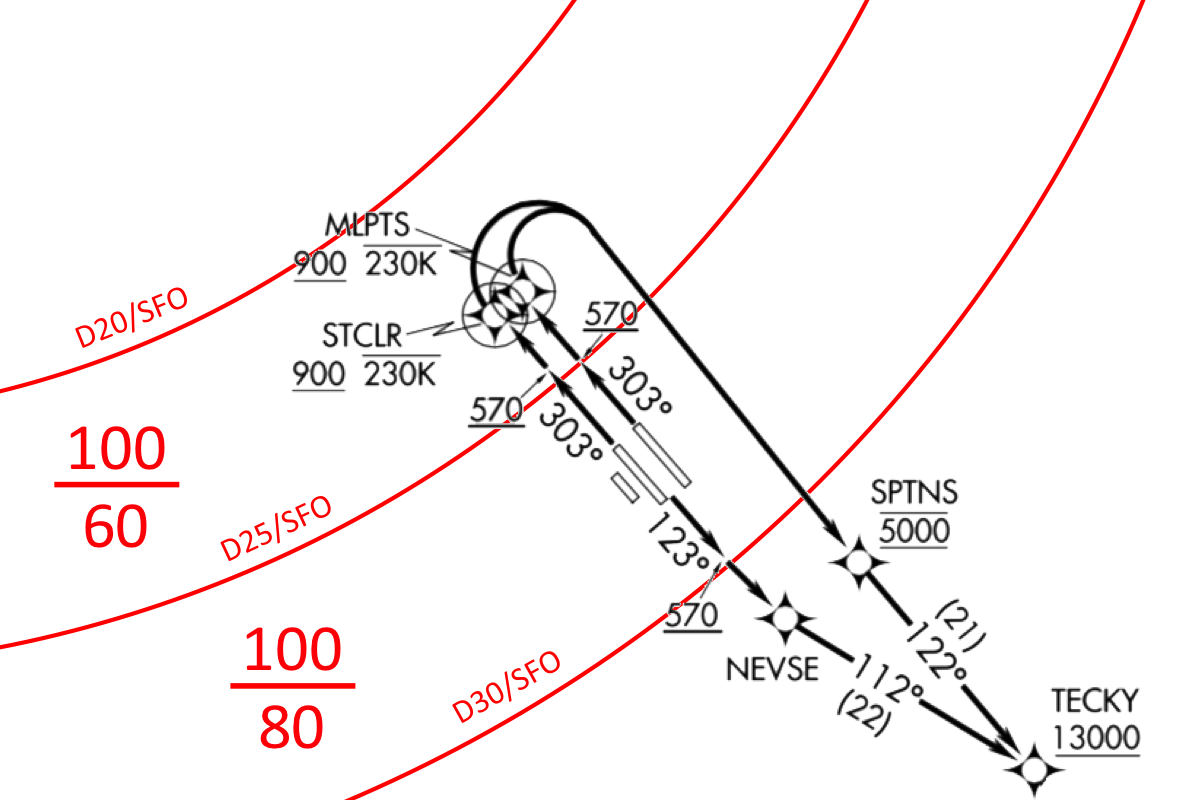

TECKY ONE Paranoid Trap, from my notes, taking KSJC TECKY ONE Departure (FAA SW-2, 28 May 2015 to 25 Jun 2015) ground track and altitude restrictions and using KSFO Class B Airspace Restriction overlay.

You may have heard of 14 CFR 91.117(c) and you may even know what it says:

No person may operate an aircraft in the airspace underlying a Class B airspace area designated for an airport or in a VFR corridor designated through such a Class B airspace area, at an indicated airspeed of more than 200 knots (230 mph).

Source: 14 CFR 91, §91.117(c)

But how often do you consciously plan for it? The controller also knows the rule but may not care until the day the sky is crowded with smaller aircraft that are having trouble spotting you in time to avoid a collision. You can be sure that on a day that it does matter the controller’s opinion will carry more weight than yours. Consider the San Jose TECKY ONE departure published on January 8, 2015.

If you simply pull up the departure procedure, read the narrative, and mentally fly the solid black line, you can be forgiven for thinking you can accelerate to 230 knots right after takeoff. The first waypoints departing Runway 30 left or right have two restrictions: you must be at least 900 feet in altitude and you cannot be faster than 230 knots. Since we are normally keyed to remaining below 250 knots when below 10,000 feet, we tell ourselves our new target speed is 230 knots until passing STCLR or MLPTS.

The flight management systems on many airplanes will dutifully accelerate to that speed, Class B overhead or not.

NORCAL Departure Control would be fully within their rights to point out that you are flying below the San Francisco Class B airspace and your speed cannot exceed 200 knots under 14 CFR 91.117(c). The fact the Class B is not mentioned or depicted on the departure procedure is no excuse. There have been violations issued and NORCAL has been called several times on the discrepancy:

Pilots are reminded that the aircraft is below the Class B airspace in the turn and then just prior to SPTNS. Several pilots have had Pilot Deviations filed against them for exceeding the 200 KIAS limit below the Class B.

Source: NBAA Airmail, February 3, 2015

An even more insidious source of Class B high-speed trouble happens on arrival, when approach control is trying to sequence aircraft for approaches. “Fly 210 till the marker,” is a clearance to fly a specific speed but it is not clearance to violate an FAR.

So how do you protect yourself from the unknown Class B area that may be lurking over your head? If your departure or destination lies underneath a Class B area you should print the chart or have it readily accessible in the cockpit. If you can overlay the chart on your avionics you should. You should also add Class B considerations to departure procedure and approach briefings.

Chances are the first person to detect a problem will be the one sitting in the pilot’s seat. You know the rules and you might, after all is said and done, realize you might have “brushed up against” a restriction. Or you may get the dreaded “call me after you land” instruction. Your first indication could very well be a certified letter.

3

The controller's hands are tied, you can be busted without them knowing it

- New York: an Air Canada jet was taking off at LaGuardia Airport on one runway, a USAirways plane was approaching to land on a intersecting runway. Fearing a collision, a tower controller radioed: USAir nine twenty, go around to make a second approach.

- The USAirways jet pulled up, but then the copilot at the controls spotted the airborne Air Canada jet crossing right in front. Look there, the copilot shouted to the captain as he ducked his jet under the Air Canada plane. The jets missed by 20 feet, so close that the USAirways captain feared his tail would slice through the Air Canada plane passing overhead. Never-the-less, this near-collision April 3 last year was never reported by either air-traffic-control or his supervisor to Federal Aviation Administration officials. It was only after the USAirways pilots complained to the National Transportation Safety Board that the seriousness of the event began to emerge.

Source: Wall Street Journal, "Duck and Cover Up"

Subsequent investigations uncovered a pattern of these failures to report and prompted the FAA to institute corrective programs called everything from “Air Traffic Quality Assurance” to the “Operational Error Detection Program.” Real-time software systems, such as the Traffic Analysis Review Program (TARP), automatically detect, flag, and report loss of separation and other occurrences at air traffic terminal facilities without controller input or knowledge. A controller may no longer have the ability to forgive an infraction and may in some cases be at risk when deciding to do so.

4

The Aviation Safety Reporting System (ASRS) is more and less than you think it is

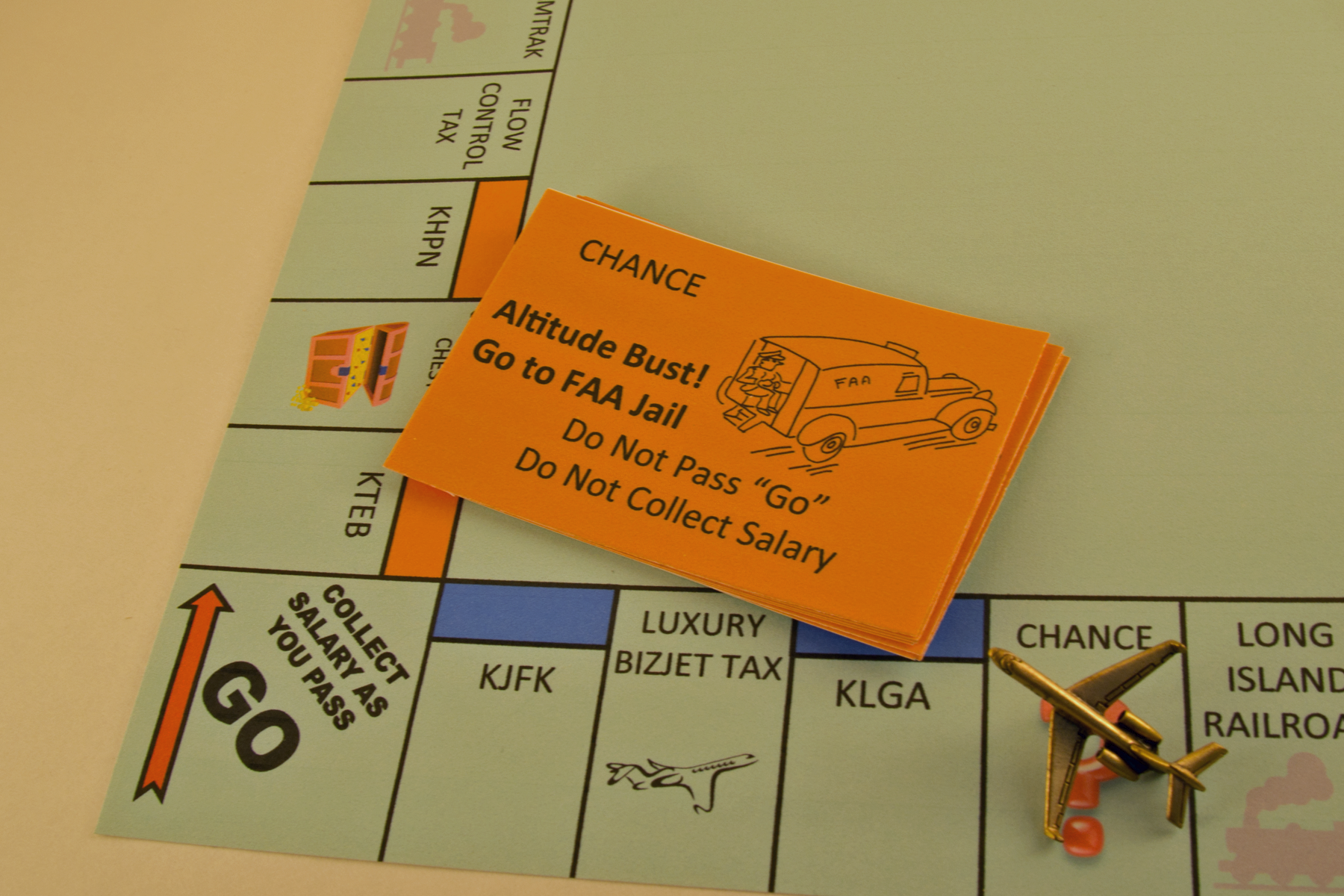

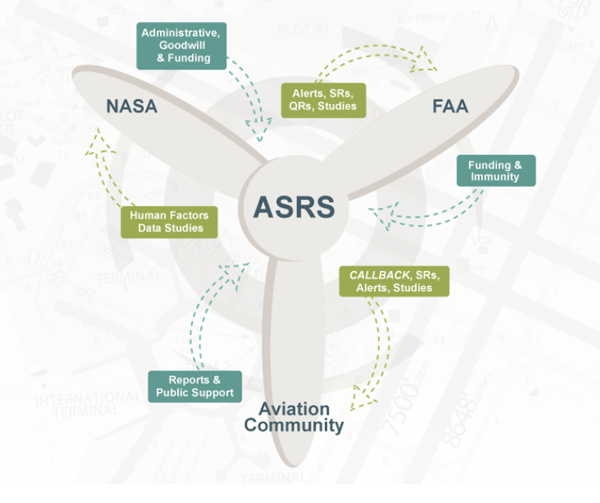

In 1975 the FAA enlisted the help of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to act as a third party to receive and process Aviation Safety Reports from pilots, controllers, and other users of the National Airspace System. The intent was very good, of course. Allowing the free, unrestricted flow of information gave the FAA the data it needed to find problems it would not normally get and take the necessary corrective actions. In return, it was said, licensed pilots, air traffic controllers, dispatchers, mechanics, and others would get a form of immunity, a “get out of jail free” card of sorts. But it doesn’t really work that way. The Aviation Safety Reporting Program is outlined in Advisory Circular 00-46E, and FAA Joint Order JO 7200.20 Voluntary Safety Reporting Programs. The ASRS was designed in 1975 but has since been modified three times, meaning what you know about the program may have changed.

Background

ASRS Stakeholders, from ASRS Program Briefing, slide 10.

- Background. Designed and operated by NASA, the NASA ASRS security system ensures the confidentiality and anonymity of the reporter, and other parties as appropriate, involved in a reported occurrence or incident. The FAA will not seek, and NASA will not release or make available to the FAA, any report filed with NASA under the ASRS or any other information that might reveal the identity of any party involved in an occurrence or incident reported under the ASRS. There has been no breach of confidentiality in more than 34 years of the ASRS under NASA management.

- Regulatory Restrictions. Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 91, § 91.25 prohibits the use of any reports submitted to NASA under the ASRS (or information derived therefrom) in any disciplinary action, except information concerning criminal offenses or accidents that are covered under paragraphs 7a(1) and 7a(2).

- Non-ASRS Report. When violation of the 14 CFR comes to the attention of the FAA from a source other than a report filed with NASA under the ASRS, the Administrator of the FAA will take appropriate action.

Source: AC 00-46E, ¶5.

Air Traffic Controllers

Filing a VSRP report does not preclude the FAA from performing its responsibilities pertaining to event reporting, quality assurance, quality control, and oversight; or employees from fulfilling their obligations to any investigative process. The FAA may conduct an independent investigation of any event disclosed in a report.

Source: FAA Order JO 7200.20, ¶2-7.

When an employee submits an ASRS report, disciplinary action may not be taken for a reported event if all of the following conditions are met:

- The employee’s action or lack of action was inadvertent.

- The employee’s action or lack of action did not involve a criminal offense, accident, or action under 49 U.S.C. § 44709, which discloses a lack of qualification or competency.

- The employee shows proof that within 10 days after the occurrence, he/she completed and submitted, electronically or by mail, a report to NASA’s ASRS. When completing a VSRP report, employees may choose to electronically submit a copy of their VSRP report to ASRS via the VSRP database.

Source: FAA Order JO 7200.20, ¶2-13.b.

There are pilots who get pretty upset by the word "employee" in this FAA Order. Keep in mind that in ¶1-2 the order clearly states: "This order applies to all ATO personnel directly engaged in and/or supporting air traffic services and only to events that occur while acting in that capacity." Pilots have their own protection:

Pilots

The Administrator of the FAA will not use reports submitted to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under the Aviation Safety Reporting Program (or information derived therefrom) in any enforcement action except information concerning accidents or criminal offenses which are wholly excluded from the Program.

Source: 14 CFR 91, §91.25

Notice it does not prohibit enforcement action, just the use of the information in the ASRS report.

The FAA considers the filing of a report with NASA concerning an incident or occurrence involving a violation of 49 U.S.C. subtitle VII or the 14 CFR to be indicative of a constructive attitude. Such an attitude will tend to prevent future violations. Accordingly, although a finding of violation may be made, neither a civil penalty nor certificate suspension will be imposed if:

- The violation was inadvertent and not deliberate;

- The violation did not involve a criminal offense, accident, or action under 49 U.S.C. § 44709, which discloses a lack of qualification or competency, which is wholly excluded from this policy;

- The person has not been found in any prior FAA enforcement action to have committed a violation of 49 U.S.C. subtitle VII, or any regulation promulgated there for a period of 5 years prior to the date of occurrence; and

- The person proves that, within 10 days after the violation, or date when the person became aware or should have been aware of the violation, he or she completed and delivered or mailed a written report of the incident or occurrence to NASA.

NOTE: Paragraph 9 does not apply to air traffic controllers, who are covered under the provisions of the Air Traffic Safety Action Program (ATSAP), as described in the ATSAP Memorandum of Understanding (MOU).

So air traffic controllers are covered by the FAA Order cited earlier, we pilots are covered by this AC

Source: AC 00-46E, ¶9.c.

In other words, filing an ASRS report may not get you out of a violation, but it will get you out of a civil penalty or suspension under certain circumstances. It could get you out of the violation if the investigator is so inclined, so you should file the report.

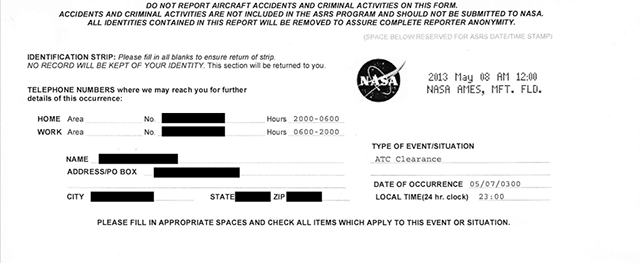

The Forms

The forms are available online (http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov) and can be either mailed or filed electronically. If the report reveals criminal activity, it is sent to the department of justice and the FAA with identifying information. If the report details an accident, it is sent to the NTSB and the FAA with identifying information. All other reports are de-identified and sent to interested parties. NASA will time stamp a Reporter Identification (ID) Strip and send that to the sender as proof of submission.

Once you have submitted the report and received the time stamped ID strip, you should lock that away for safekeeping should the FAA decide to investigate the incident.

A side benefit to the ASRS database is that we, as pilots, have access to the de-identified reports: http://asrs.arc.nasa.gov/search/database.html.

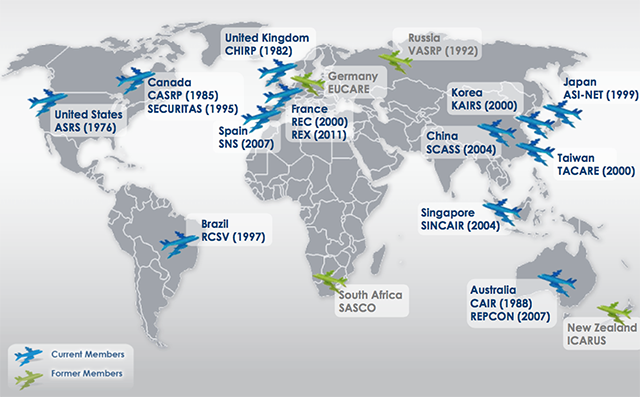

International Versions

ASRS Model Applied to International Aviation Community, from ASRS Program Briefing, slide 50.

- Australia: http://www.atsb.gov.au/voluntary/repcon-aviation.aspx

- Brazil: http://www.cenipa.aer.mil.br/cenipa/index.php

- Canada: http://tsb.gc.ca/eng/securitas/

- France: http://www.bea.aero/en/index.php

- Singapore: http://www.mot.gov.sg

- Spain: http://www.seguridadaerea.gob.es/lang_castellano/g_r_seguridad/notificacion_sucesos/default.aspx

- Taiwan: http://www.tacare.org.tw/tacare_en/main.asp

- United Kingdom: https://www.chirp.co.uk

5

Get your testimony on paper, officially (as soon as possible)

If your incident does come under investigation, an official of the FAA with an official title will start making phone calls and will start taking notes. Even if his note taking skills are not up to par and even if the people he speaks to do not have the best memories, the moment the inspector types them onto a letter with the FAA logo and signs with his FAA title, that document becomes a dated, official piece of evidence. How are you going to challenge that?

You need your own official document. You should make a written record of the incident, taking care that everything is accurate and paints the situation in a favorable light. Leave out any embellishments or unnecessary facts. Have knowledgeable friends and coworkers comb over the document with a critical eye and make edits as if your license depended on it. When you are satisfied, take it to a licensed notary republic and make it all official with your signature and the notary’s seal. The act of getting it in writing will cement the facts in your mind and having it notarized will give any future investigator pause about pursuing the case. The investigator’s notes, after all, are quite often recollections of disinterested parties that may not have been paying as close attention to your aircraft as you.

Why do you have to do this? An aviation lawyer who used to work for the FAA as a prosecutor told me that they get their side of the story on paper, sometimes months after the fact. Their recollection can be cloudy and there notes can be shoddy. But they are on paper with the official FAA logo on top and their signature as "inspector" on the bottom. If you have something that predates that, has applicable attachments, and presents a compelling argument, it will strengthen your case.

6

When the Fed calls, what you say can and will be taken out of context and used against you

If an FAA inspector meets you at the airplane or office, or even calls you on the phone, you may not be well served by saying the first thing that comes to your mind. “I want to talk to my lawyer,” however, can be taken as a sure sign of weakness. You need to think about this before it happens.

If, for example, the inspector asks you if you happened to graze the nearby Class B airspace, the right answer could be the wrong answer. Let’s say you are positive you were clear of the airspace and said so. If the inspector can produce a radar tape that says otherwise, you have lied to an official of the FAA. A better answer to almost every case would be, “I’m pretty sure I’ve flown in accordance with all rules and regulations, but I could use some time to do a normal post flight and mental debrief of the trip. May I call you tomorrow at a time of your choosing, please?”

If the inspector thinks you are a consummate professional with an innate desire to do things by the book and a priority on safety, your future endeavors should go well. The inspector does not want an ugly confrontation. If, on the other hand, you start things on an adversarial tone, they will only escalate from there.

Under FAA Order 2150.3B, a Letter of Investigation (LOI) will not be issued unless evidence shows that a violation may exist. The LOI is sent by regular mail and either certified mail, return-receipt requested, or by registered mail. It normally specifies a 10-day time for reply.

The FAA’s compliance and enforcement program is designed to promote compliance with statutory and regulatory requirements. The program provides a wide range of options for addressing noncompliance. These options include educational and remedial training efforts, administrative action in the form of either a warning notice or letter of correction, certificate suspensions for a fixed period of time, civil penalties, indefinite certificate suspensions pending compliance or demonstration of qualifications, certificate revocations, injunctions, and referrals for criminal prosecution.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 2, ¶2.b.

Although the agency has programs to encourage self-disclosure, surveillance remains the primary method of detecting violations.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 2, ¶3.c.

How long do you have? FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 4, does give some time guidance and you may have heard they have 75 days to complete the investigation (Chapter 4, ¶4.e.) but there are lots of exceptions that bring that out to 6 months, 5 years, and even further. In other words, there is no time limit.

In prosecuting both certificate actions and civil penalty actions, the FAA has the burden of proof, by a preponderance of the reliable, probative, and substantial evidence, to establish all facts necessary to satisfy each element of a statutory or regulatory violation. The preponderance of evidence standard requires that the FAA’s evidence shows that it is more likely than not the respondent committed the violation. When a respondent asserts an affirmative defense at a hearing, the respondent has the burden of proof and must establish the elements of the defense by a preponderance of the reliable, probative, and substantial evidence.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 4, ¶8.c.

All this would be fine and dandy in normal court of law, but you will not be in a normal court of law. Who gets to decide what is a preponderance of evidence when presented by the FAA? Why it is the FAA, of course. And who gets to determine if the affirmative defense you present meets that level? Why it is the FAA again!

- A letter of investigation (LOI) serves the dual purposes of notifying an apparent violator that he or she is under investigation for a possible violation and providing an opportunity for the apparent violator to tell his or her side of the story. While an LOI is not required, FAA investigative personnel should issue an LOI in most cases.

- The LOI specifies a time for reply. This time normally is 10 days. Additional time may be necessary in cases involving apparent violators who reside or have their principal place of business in foreign countries. Although FAA investigative personnel consider any reply received after the 10 days, the investigation continues even without a reply.

- AA investigative personnel send the LOI by regular mail and either certified mail, return-receipt requested, or registered mail. to establish a record of notice to the party under investigation. If the party is a certificate holder, FAA investigative personnel send the document to the current address of record. If the regular mail is returned or the certified letter or registered letter is returned as undeliverable (because it is addressed incorrectly or the party has moved and left no forwarding address), then FAA investigative personnel correct the address or obtain a new address and resend the LOI to the correct address by regular mail and either certified mail, return-receipt requested, or registered mail.. If the certified letter or registered letter is refused or returned unclaimed but the regular mail is not returned, then there is a presumption of service and FAA investigative personnel do not resend the LOI. If FAA investigative personnel deliver the letter in person, they document the delivery in the file.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 4, ¶9.a.

The LOI goes to your residence on file with the FAA, the same one that is on your license.

Why you need to be on your best behavior, always

The extent of special enforcement consideration to be given in a particular case will depend on a weighing of public interest factors. The FAA considers the following factors in any such determination:

- Whether the FAA could reasonably be expected to discover or prove the violations without the informant's cooperation.

- The seriousness of the violations disclosed by the informant and the importance of the enforcement action against his or her employer or other members of the aviation community.

- The informant's relative culpability and violation history.

- The informant's credibility.

- Whether the informant's testimony or information may reasonably be expected to contribute significantly to either an investigation of, or enforcement action against, an employer or other action in the interest of safety.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 4, ¶12.d.

You need to strike the investigator as the consummate professional who doesn't mess around in any matters related to aviation. Everyone that investigator speaks to must have the same impression of you, so the time to start building that clean as a whistle reputation is now.

7

An aviation attorney may become necessary; it is your livelihood after all

Your next stop should be with a lawyer who specializes in defending against FAA enforcement actions. Find a lawyer who has an established reputation with the FAA who can give you an honest assessment of your chances and the best way to pursue your case. If you are a member of the AOPA, you can receive a lawyer at no cost for up to 10 hours. (http://pilot-protection-services.aopa.org)

Give the lawyer all the facts and be honest. A skilled aviation law attorney can paint a picture for the FAA that includes your background and experience as a professional aviator. A cut and dried case against you can be turned into a tale of a good pilot trapped by difficult circumstances that will never happen again. Or a shaky case built on circumstantial evidence could end your flying career for good. The difference could very well be determined by your legal representation.

Aviation Lawyer Edward J. Page of Carlton, Fields, Jorden, Burt, P.A., offers advice based on years of experience working on behalf of the FAA and on behalf of pilots:

- “Be courteous to ATC, ramp folk, the FAA, and others. If you decide to talk at anytime, make sure it’s accurate, truthful, and candid.”

- “Make a NASA report every time you are involved in an incident.”

- “Consider grounding yourself after an incident until you speak with an aviation lawyer.” (This shows your earnestness to an investigator and could count as “time already served” if you get a suspension.)

- “Consider remedial training.” (This also shows your earnestness to an investigator.)

What are they going to do?

The sanctions are outlined in FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7. If you get to this point, you might want to study this chapter to put your mind at ease or to at least give yourself a peek into your future. For now, however, a few things of note:

The FAA revokes a certificate when a certificate holder lacks the qualifications to hold the certificate. The certificate holder’s continued exercise of the privileges of the certificate in such circumstances would be contrary to safety in air commerce or air transportation and the public interest. Revocation is appropriate whenever a certificate holder’s conduct demonstrates a lack of the technical proficiency or a lack of the degree of care, judgment, or responsibility, required of the holder of such a certificate.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶2.b.(2)

The FAA generally revokes an individual’s certificate or rating whenever he or she demonstrates a lack of willingness or ability to comply consistently with statutory or regulatory requirements. A lack of willingness or ability to comply may be demonstrated by such things as repeated or deliberate violations or by violations that involve grossly careless or reckless conduct. Even a single violation may be sufficient to warrant a conclusion an individual lacks qualifications. The FAA ordinarily revokes all certificates of a person who commits a violation involving intentional falsification.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶2.b.(3)

The decision whether to prosecute a particular case is based on a review of the evidence and relevant policy and litigation considerations. The agency exercises broad discretion in both the initial decision to bring a legal enforcement action, and in any later determination to compromise or settle a case based on various considerations. The FAA's discretion in these areas is absolute and presumed to be immune from review.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶3.b.

Few areas of our government are granted such absolute powers immune from review.

Certificate holders with greater levels of experience may be held to a higher standard. Thus, for example, commercial pilots may be held to a higher standard than private pilots and airline transport pilots may be held to an even higher standard than commercial pilots.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶4.c.

A violation-free history is the expected norm, not the exception and, therefore, is not a mitigating factor. Sanction ranges in the table generally represent the normal range of sanction for a single, first-time, inadvertent violation.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶4.h.

The FAA has programs that allow persons to report voluntarily apparent violations and receive lesser enforcement action provided certain criteria are met. These programs include the aviation safety reporting program, the voluntary disclosure reporting program, and the aviation safety action program. Besides these programs, the FAA may grant special enforcement consideration under certain circumstances to a person who, incident to his or her report of another's violations, voluntarily discloses his or her own participation in the same or related violations. This special enforcement consideration may range from mitigating the sanction to determining that no enforcement action is required.

Source: FAA Order 2150.3B, Chapter 7, ¶4.l.

Appendix B of FAA Order 2150.3B contains several tables of sanction guidelines. A general aviation operator, for example, can expect a 30- to 90-day suspension for exceeding a speed limitation.

Bottom Line

In the end, the FAA may decide you are innocent or that there is insufficient evidence to issue a violation. If the FAA decides a violation did occur, you could end up with oral or written counseling, remedial training, instructions to voluntarily surrender your certificate, a suspension of your certificate, revocation of your certificate, civil penalties, and various combinations of each. While appeals to the NTSB are possible, the board is required to defer to the FAA in most cases.

References

(Source material)

14 CFR 91, Title 14: Aeronautics and Space, General Operating and Flight Rules, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Transportation

Advisory Circular 00-46E, Aviation Safety Reporting Program, 12/16/11, U.S. Department of Transportation

ASRS Program Briefing, NASA, August 2013

"Duck and Cover Up FAA Scary Finding: Controller's Sometimes Conceal Close Calls, Wall Street Journal, December 6, 1999

FAA Order 2150.3B, FAA Compliance and Enforcement Program, 10/01/07

FAA Order JO 7200.20, Voluntary Safety Reporting Programs (VSRP), January 30, 2012

NBAA Airmail, February 3, 2015, San Jose Intl Tecky One (RNAV) Departure Procedure

United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit., Jane F. Garvey, Administrator, Federal Aviation Administration, Petitioner, f. National Transportation Safety Board and Richard lee Merrell, Respondents. No. 98-1365. Decided September 21, 1999