You’ve probably heard there is a pilot shortage of unprecedented magnitude. Half of today’s major airline captains will be retired in ten years. Business aviation captains are getting older and it is no longer unusual to run into pilots having to worry about age 65 restrictions in some countries. That’s good news for the next generation of pilots; right?

— James Albright

Updated:

2016-12-01

Maybe so, but consider this: experienced pilots once destined to mentor the next generation of aviators are too busy flying to instruct. Some pilots coming of age as captains today will have never heard a “There I was” story from the days when engines routinely blew themselves apart. Our industry has a pilot shortage and that has led to a shortage of the highest level of aviation mentor.

Mentor. The word speaks volumes to just about any aviation professional. The job at hand is so complex that it would be next to impossible to achieve professional status without a little help along the way. Becoming a qualified pilot, engineer, mechanic, dispatcher, flight attendant, or anyone involved in aviation, is not something any person can accomplish solo. But anyone can be a mentor; we need more of the highest level of mentors. We need aviation gurus.

Guru. The word seems almost out of place in an aviation context. And yet many of us know a few aviators who have earned the title. These are the “go to” experts who seem to know more about the airplane than those who built it, more about the steps needed to fly than those who wrote the procedures, and more about the ins and outs of aviation than just about anyone else. But being an “aviation guru” is far from what the metaphysical connotations of the word would imply. It is more about learning and instructing; an aviation guru is an aviation mentor on steroids.

If you’ve never been a mentor this might be lost on you. But anyone who has spent any amount of time in the mentor role will tell you that it is a two-way street. The mentor gets just as much from the relationship as the “mentee.” The act of teaching forces the teacher to up his or her game to assure everything taught is accurate. We should all attempt to learn what it takes to become an aviation guru. The act itself will make us better aviators. Becoming an aviation guru is an excellent way of giving back to a profession that has given us so very much. So let’s do that. Along the way we can examine the careers of a few aviation gurus to better understand what makes them tick and to figure out how we can all assume the mantle as the next generation of gurus.

1 — What motivates most gurus?

2 — How most gurus get their start

4 — Another path: find need and fill it!

1

What motivates most gurus?

We all get our start as novice aviators and then apply varying amounts of effort and zeal trying to remove the novice tag from our resumes. Typically that involves a lot of training, note taking, and investigation. For all mentors turned guru, there comes a time when the role of question answerer overtakes that of question asker.

For Chris Parker the role of “Mister Answer Man” was a natural fit. “I’ve always been curious, and with aviation I really tried to dig into the manuals to find out not only to find out the what, but the why behind it. I felt that once you know the why, you can better understand and if need be, debate the what.”

He soon realized he was becoming the “go to” person in his circle of Challenger pilots for all matters from the aircraft, to regulatory and international operations. His desire to share started when he was a young flight instructor presenting safety seminars to other pilots as part of the FAA’s safety program. Next he ventured into writing for AOPA’s Flight Training Magazine. But it was his article “Are Part 135 Line Checks Necessary” in the May 2004 issue of Business & Commercial Aviation magazine that brought him prominence in the business jet world. Soon he was fielding questions from across the country and his role as aviation guru began in earnest.

When a pilot graduates from keeping in the books for one person (him or herself) to fielding questions from a cadre of other professionals, the need for accuracy increases dramatically. “Once I realized other pilots were calling me for advice, I became even more motivated to learn and obtain accurate and timely information. It was a responsibility I did not take lightly.”

Most aviators struggle to keep up-to-date in an industry where constant change is the norm. An aviation guru has the added burden of always wanting to know more, to expand the knowledge base. This has been made easier with the Internet, of course. Chris makes liberal use of technology; but he isn’t afraid to engage the experts one-on-one. “There were always the usual suspects: civilian aviation books, military training books, training providers, manufacturer’s manuals, the alphabet groups, conferences, other pilots, etc. But I would have to say some of the best nuggets I found came from people, and sometimes at unexpected places. I managed to visit San Francisco ARINC, Los Angeles Center, and LAX tower. At a routine maintenance event at an MRO, I would have a quick conversation with a maintenance tech and learn more in 5 minutes that in 5 hours buried in a maintenance manual. Or even a phone call to the friendly FAA TERPS man in Oklahoma City. What I’ve found is that almost anyone is willing to share their struggles and point of view if you are genuinely interested in what they have to say.”

Looking at Chris’ curriculum vitae can be a bit intimidating for a younger pilot thinking about the uphill knowledge climb ahead. How does one take that first step to becoming more than just a pilot?

“Nurture your passion. If you don’t have it, you won’t put in the time to become a true professional. And take notes. Someone much smarter than me said, ‘the weakest ink is better than the strongest memory.’ I agree. Taking notes, putting pen to paper, has a tendency to cement what you’ve learned. And finally share what you know. Sharing helps you take responsibility for the accuracy of your knowledge, because others may rely on it.”

2

How most gurus get their start

There is a common theme among many aviation gurus that begins with their first days in aviation. It all starts with a desire to become a better pilot, mechanic, or other aviation professional. These men and women become known as meticulous note takers, and tireless researchers. They all have a compulsion to share. It is only a matter of time before they become the “go to” resources for the rest of the community.

Some aviation gurus appear to be a bit introverted and most have a quiet modesty that may disguise their true identities as “uber gurus.” Robert Hare, a retired Challenger, Gulfstream, and Falcon pilot admits to the introversion and I can attest to his modesty. His path to the road to becoming an icon in the Gulfstream IV world may sound familiar to many future aviation gurus.

“I was one of those obnoxious students that asked all the detailed questions because I wanted to understand the inner workings of the systems and procedures.” He says his instructors were very good and knew their subjects cold. He took copious notes, hoping to review everything prior to each recurrent. “But my notes were so hard to read after that passage of time, I rarely got much out of them.”

With the advent of word processors, Robert was able to transcribe his notes after every training session. He folded future notes into the previous versions and organized everything into easily referenced chapters. The notes became so expansive, he applied extra effort to make sure they were accurate. “My goal was to aid my mediocre memory. And like the old saw: Cutting firewood warms you twice, this process of repetition and organizing added to the value of the notes for me.” After a while his peers noticed and his notes proliferated. Gulfstream pilots who had never met him were using his notes as study materials. He had arrived as an aviation guru. The effort not only made him a better pilot, but also raised the bar for the entire industry.

Most every mentor got his or her start from another mentor. “Associating with people way smarter and more capable than myself helped to guide and motivate me. Fear of failure motivated me to minimize the chances of failure. He who teaches, learns. I would sponge up every bit of operational experience I could. I never minded saying I didn't know an answer, but as time went on, I had to say it less.”

Robert spent many years as an instructor for both FlightSafety International and CAE SimuFlite, broadening his impact on the industry and providing the time and experience to hone his guru “chops.” But not all gurus have this type of formal teaching background. In fact, most gurus come from the trenches.

3

The operational guru

Ivan Luciani admits that his life was defined at the young age of eight while watching the U.S. Thunderbirds perform in F-4 Phantom IIs; he was hooked. From the beginning of his flying career he realized the key to success was in his attitude toward learning. “Most companies won’t consider you for a job unless you have at least 1,000 flight hours. That is why we consider reaching the first 1,000 hours to be one of the most difficult obstacles to overcome. Granted – with a total of 250 flight hours you are just learning to crawl. It takes quite a bit more flying experience to learn how to walk and even more to learn how to run. Obtaining your Commercial Pilot certificate with Instrument, Single and Multi-Engine ratings is simply a license to learn. You still have a long, long way to go.”

Ivan’s path took him to Hong Kong where he became the Flight Training Manager for a 25 aircraft company flying everything from a Citation Sovereign to a Boeing BBJ. As a pilot he relied on detailed written notes to breakdown complex subjects into more easily understood lessons. The word soon spread and those notes became required reference material.

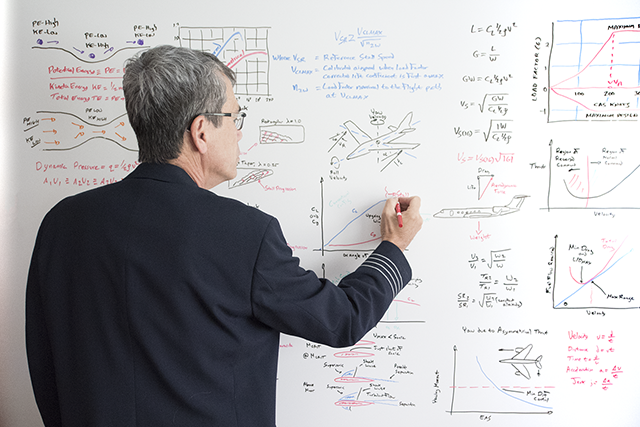

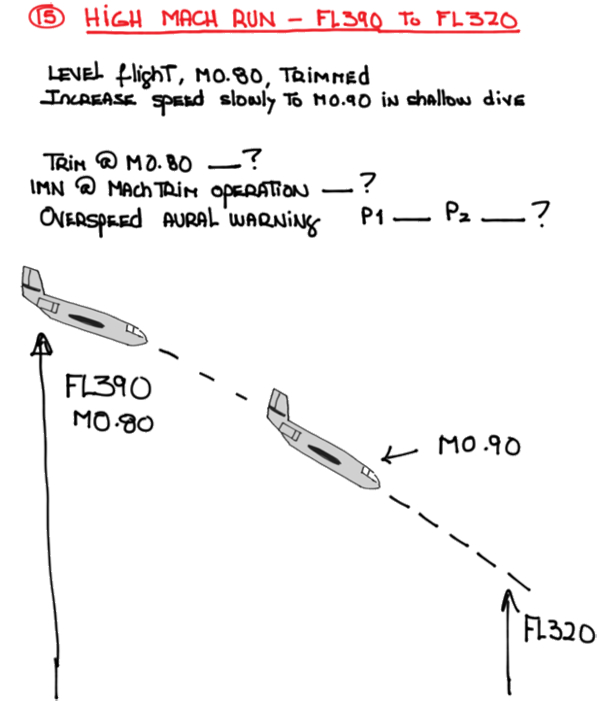

I first heard of Ivan Luciani when reading his thoughts on how to best conduct a functional check flight. His functional check flight notes became my lesson on how to best write easily understood test profiles.

Ivan believes good instructors can turn any flight into a training exercise. A flight evaluation can become the best teaching moment; the students are bound to pay attention. “During line checks my ultimate goal is to provide meaningful feedback that would help make these pilots better, individually and as a crew. I am one of several company pilots who have gladly undertaken this role.”

Along the way to becoming an aviation guru, Ivan learned one of the fundamental truths of being a professional pilot: the best way to learn is to teach. Teaching forces you to get it right. “Being able to recite limitations, aircraft systems and procedures is just not good enough. I want to understand the background behind the limitations and procedures, how the systems work and evolved over the years, and most importantly, how each separate system/component integrates with everything else to form the whole.”

Another responsibility of elevating one’s status from mentor to guru is the need to get it right. “This is super critical as incorrect/inaccurate information can adversely affect others, not to mention destroy your own credibility. If it is not supported by a recognized source, such as Gulfstream or FlightSafety International, I don't use it. I am very critical of pilots who think they know better than the manufacturer and implement procedures that deviate/contravene those developed by the manufacturer. The exception would be cases where the manufacturer provides guidelines to help operators develop their own procedures.”

Many aviation gurus adopt or have the instructor position formally assigned; it is part of their job and they fully embrace their roles to teach others. But not all gurus are former instructors; some fill that teaching role as purveyors of information.

4

Another path: find need and fill it!

While many pilot gurus tend to get their start specializing in a specific aircraft type and then branch onto specific operational aspects of their profession, some pilots like to paint with a broader brush. Much broader!

Mark Zee may have the broadest brush of them all. He got his start as an air traffic controller, moved on to become an airline station manager, a flight dispatcher, and then an airline pilot for a major carrier.

Through these experiences he realized that there are few more challenging aspects of aviation than international operations. These challenges are made even tougher because they are changing faster than anyone can really catalog with less than a full time cadre of gurus. Mark couldn’t find a “one stop” location for the information he needed, so he invented it.

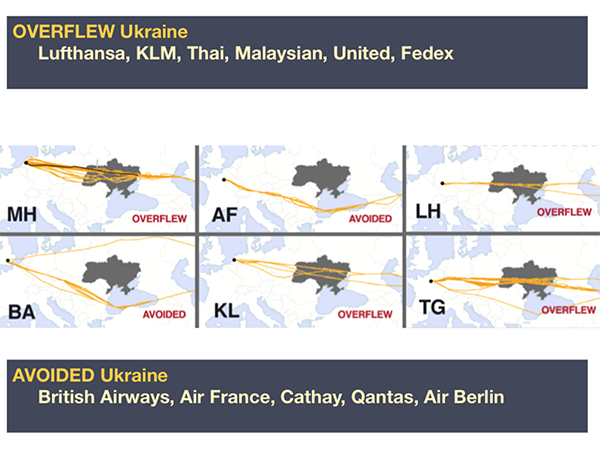

He started with “The Airline Cooperative,” a group of 220 airlines that work together as peers to share knowledge and improve safety, security, and efficiency. The idea is simple. On July 17th, 2014, Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 was shot down while overflying the Ukraine, however, several other airlines knew well enough to avoid the area. Why wasn’t this knowledge shared? That’s one of many reasons The Airline Cooperative was created.

From The Airline Cooperative followed the Flight Service Bureau, an international flight operations partner available to all business and corporate aviation, as well as the airlines. I am a member and have found it the best way to keep on top of all international flight operations. And just this year Mark unveiled OpsGroup (ops.group), a platform for pilots, controllers, dispatchers, and managers to ask questions, provide answers, and to learn from peers.

These organizations provide answers to the most recent vexing questions, all without a sales spiel or push to buy something. Their websites provide a platform for sharing accurate knowledge. “The more you learn, the more you realize you don’t know. Early on, I always thought there was a finite amount of knowledge for a specific area of aviation, and that when I had finally learned everything, I’d be able to call myself a pilot, a controller, a dispatcher. Now I see a 180-degree reversal in my thinking. I don’t make it a secret if I’m not sure of something. The most dangerous people in aviation are the ones that pretend to know it all. Everyone is winging it to some degree. So, if I can make it easier for people to ask questions, and feel OK doing so, then I think I’ve achieved something.”

There is no question Mark is having a worldwide impact, but he got his start in more humble beginnings. And that leads us full circle to our final example.

5

The next generation of gurus

Like each of our gurus, Jason Herman understands he needs to stay in the “learn mode” and will never have all the answers. His efforts to become a better pilot and his passion to share knowledge promise to elevate his status from mentor to aviation guru.

Jason earned his pilot’s license at 17 years of age and earned his first advanced licenses at the Purdue University Department of Aviation Technology. He is now the lead captain of a Cessna Citation CJ4 account and works on several National Business Aviation Association committees. But he got his start on his road to becoming an aviation guru by simply picking up the phone. He became a de facto “go to” person for many colleagues on all matters pertaining to the CJ and Part 135 compliance. “As is often said during primary training for a check ride or qualification event, you don’t necessarily need to know everything, but you should at least master the fundamentals and be very familiar with where to find answers to the remaining questions within your available resources.”

What separates an aviation guru from someone who is very knowledgeable and otherwise gifted with systems and procedures is a passion to share that knowledge and those gifts. Jason started with one-page reference sheets he found useful for many aircraft procedures, but he didn’t stop there. His written notes and procedures became laminated documents spread through the community. He and like-minded colleagues used secure Internet file sharing websites to insure resource documents and other training materials got to those who needed them.

While Jason is still very young and will be building upon his experiences in the years to come, he is well on his way to becoming an aviation guru.

6

The aviation guru shortage

The pilot shortage is real and that means the professional pilot force is “out there,” doing the job at hand. It would be tragic if the best and brightest of those were too busy flying to mentor the next generation. We have a shortage of aviation gurus.

We all have a little of what makes each of our example gurus the kind of “go to” resources so vital to keeping things safe. Sometimes all we need is the motivation and a little knowledge on how to take it up to the next level:

Study all available resources.

Dig deeper; sometimes a maintenance manual will shed light on what a pilot manual glosses over.

Edit your notes; a second or third look can turn idle scribble into gems of knowledge.

Share; there was a generation before you and there will be a generation after you.

Technology can turn us all into brilliant technical writers and illustrators. It has never been easier to become an aviation guru. Why not you?