We all end up with a pilot's license that says we are qualified pilots in command and most of us have even occupied the left seat of something or other along our paths to becoming professional pilots. But there is something magical about the left seat of heavy iron. The first time you occupy that seat as the pilot in command in an aircraft that requires two pilots, well that's special.

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-07-24

For me, the first time was in a Boeing 707 (EC-135J) on May 22nd, 1984. I passed my upgrade check ride the week previous and was forever changed as a pilot.

6 — Taxiing the entire airplane

7 — Landing on runway centerline

9 — Getting over the new captain syndrome

There is more research available in a few very good books and movies:

- Aircraft Command Techniques: Gaining Leadership Skills to Fly the Left Seat, Sal j. Fallucco. An airline pilot's memoir with a few useful lessons for the new captain.

- Airport. This is the 1969 movie with Dean Martin as the airline captain. It is an entertaining look at a captain's decision making process.

- Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Malcolm Gladwell. How instinct works for some and not for others.

- Fate is the Hunter, Ernest K. Gann. The classic memoir of an airline pilot back in the days when flying was anything but routine.

- The Field Guide to Understanding Human Error, Sidney Dekker. A look at how to improve from failure.

- Flight Lessons 1: Basic Flight, James Albright. Eddie's path to the left seat begins with jet trainers and the right seat of a KC-135A tanker, where he absorbs the lessons from the left seat.

- Human Error, James Reason. Psychology and human error in an age of technology.

- So You Want to be a Captain?, Royal Aeronautical Society Flight Operations Group, 1 September 2010. This is an interesting look at the legal aspects of command and flight deck management. It even includes a few case histories.

- Twelve O'Clock High. This is a classic in military leadership courses about how to weigh the human part of leadership against the mission part of command. It offers a lesson for crew leadership: sometimes you have to look beyond the people to get the job done.

1

Proper seat position

It is to your advantage to find the seat position intended by the manufacturer so that your eyes are at exactly the right position every time you sit in the cockpit. This may not be the most comfortable position and you may think it robs you of a little depth perception because you have less between you and the aim point. But sitting too far back decreases your look down angle and, in effect, lowers your effective visibility.

But there is another reason you may not have realized if you are just moving over to the left seat. You are positioning your large airplane into some tight taxiways and ramps. You need to have a constant sitting position so that your taxi cues (more on that here shortly) are always the same. So how do you do this?

The best solution are eye position alignment indicators, example shown. Other methods include sighting down your fist atop the glareshield and counting clicks on the seat tracks. If you fly more than one aircraft, however, you may find variation in glare shields and seat tracks. Find a good method and use it, every time you get into the seat.

2

Wheel brake technique

Most large aircraft use combination toe brakes / rudder pedals. Even if you've used these before on a smaller aircraft, there are a few intricacies you might not be familiar with:

- Many aircraft brakes can seem "grabby" to someone not used to the problems with heavy aircraft and large inertia. Learning how much brake pedal deflection is needed to start the application is half the battle, and then being patient. Try to think of applying varying pressures from your feet to the pedals, as opposed to specific amounts of deflection.

- Be aware that brake effectiveness changes with brake temperature and quite often applying a constant pressure can result in increasing braking without increased effort. This is especially useful on landing, where avoiding the urge to vary brake pressure can avoid the inherent "jerkiness." More about this: Jerk.

- Be advised the newer technology carbon-carbon brakes wear differently than steel brakes and sometimes the number of applications is more important than the duration of application. More about this: Carbon-carbon Brakes.

3

Tiller technique

Every system is different so you will have to get into your aircraft manufacturer's books to learn yours. Once you've done that, a few notes on how to handle that tiller smoothly:

- Do not consciously move the handle with the intent of deflecting the nose wheel, this will result in a jerky nose and may even put excess wear on the tire. You should think of applying small pressures, left or right, and seeing how the nose reacts. You then adjust the pressure up or down.

- Be aware that differential brake pressure can undo or exaggerate your efforts with the nose wheel. Until you are comfortable with applying both at once, try to get comfortable with the nose wheel without the brakes.

- If you nose wheel is spring-loaded to the center position, try not to stop with the nose wheel deflected in either direction. This is also good practice for nose wheels that do not have a centering tendency.

With or without a tiller, it can be difficult to taxi straight along a taxiway without the "jitters." I can spot it in a new captain or one coming from a smaller aircraft: the nose of the aircraft moves "nervously" left and right as the pilot tries very hard to keep on centerline. To stop this, try focusing ahead a few hundred feet, not just forward of the aircraft. Then try to remember you should be applying pressures to the tiller or rudder pedals, not movements.

4

Nose wheel placement

Find a long, straight taxiway line to line up on and have an outside observer confirm you are on centerline. Look for a reference point on your glareshield or the nose of the aircraft that lines up with your eyes. Remember there will be parallax from your seated position to the left of the aircraft’s center. (There could also be parallax created by the windshield’s thickness.) Alternatively, some pilots line up their knees or feet with where they perceive the centerline to be.

5

Main gear placement

You can get a pretty good idea of where your main gear are from the cockpit by learning their relationship to the limit of your vision from the seated position:

- Align your eyes to your normal sitting position.

- Have another pilot stand outside, abeam your eyes, with a cell phone.

- Have the pilot inch to and from the aircraft until you can just barely see his or her feet on the ground.

- Ask the pilot to remain in that position.

- Leave the cockpit and compare the pilot’s feet to the track of the main gear. That is how much space you have between the limits of your vision from the seated position to the main gear wheels.

6

Taxiing the entire airplane

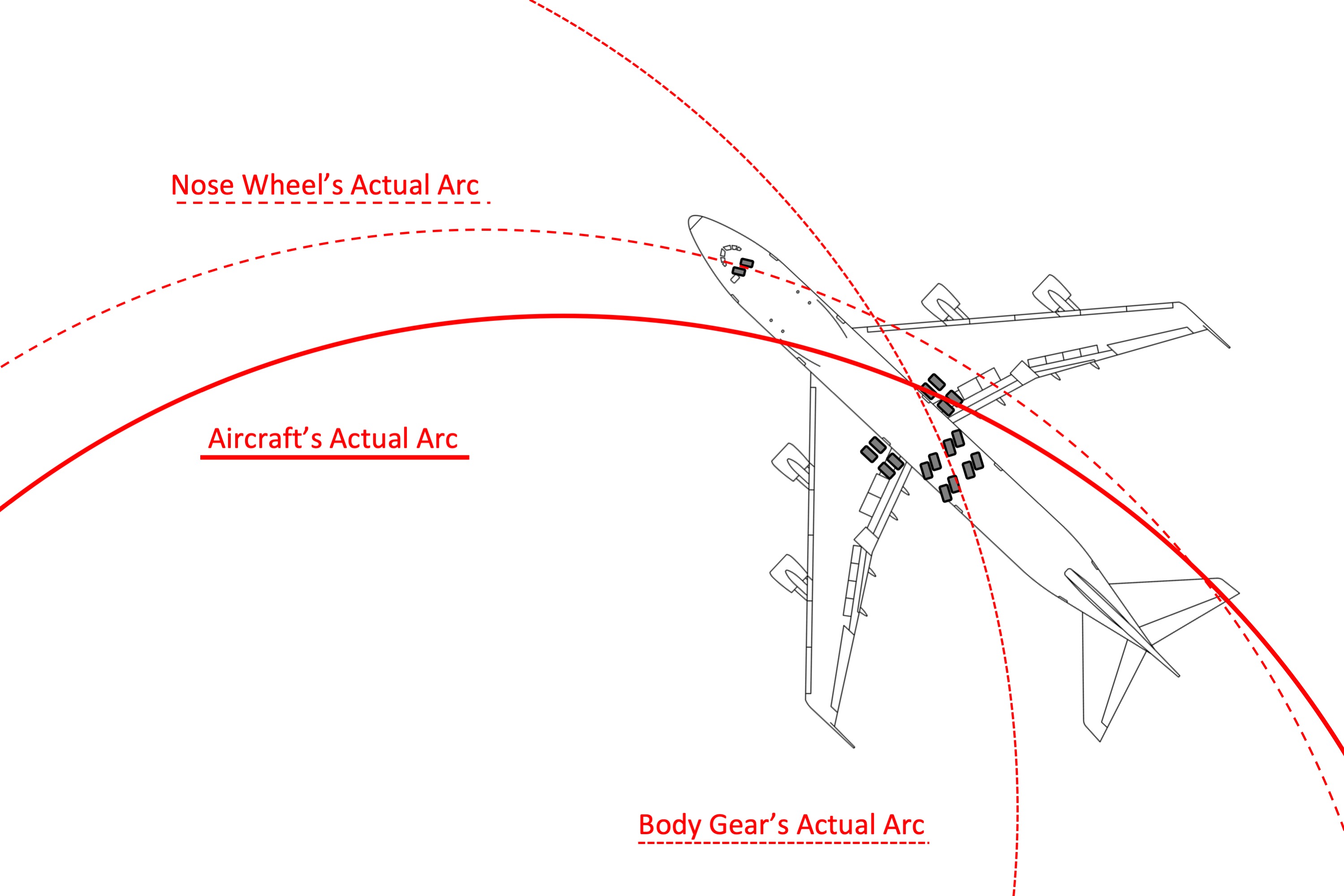

Because the main landing gear on most aircraft are fixed pointing forward and the only turning force on the pavement is produced by the nose wheel(s), the aircraft does not describe a perfect arc when turning. In an even more complicated set up, the Boeing 747's aft-most set of gear, called the "body gear," can be steered opposite the nose wheels to tighten the turn radius. In that case the center of the arc is described by both sets of steerable gear. The Boeing 747 pilot must visualize the turn and realize that in a tight turn, the taxiway center will be behind his or her seated position and that the wing tips and tail will whip about further away from the center and at greater speed.

These lessons apply to more conventionally equipped aircraft, but the effects are the same:

- The maximum deflection of the nose wheel determines how large an arc the inside main wheel will describe. The extreme case occurs if the nose wheel can pivot 90°, in which case the aircraft turns about the inside wheel.

- The nose wheel's distance behind (or ahead) the pilot determines how far the pilot must delay (or lead) all sharp turns.

- The difference in distances between the inside wheel and the nose wheels, the outside wing tip, and the tail determines the pilot's need for ground spotters to ensure all parts of the airplane remain unscratched.

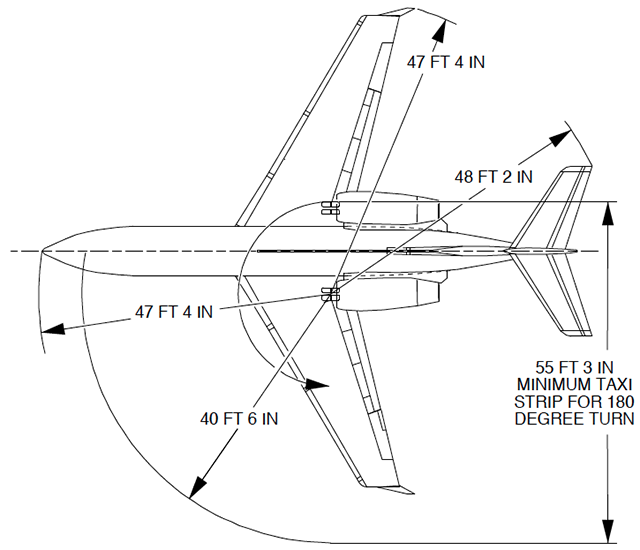

Taxi Width, from G450 Aircraft Operating Manual §2A-06-00 Figure 4.

In the case of a G450, for example:

- The nose wheel can turn 82° so a minimum turn describes a very small circle on the inside landing gear and of about 15' on the outside landing gear.

- The nose wheel is just a few feet behind the pilot but the center of the turn is about 50' behind the pilot's eyes. So the taxiway line must be passed by a distance between the nose and main landing gear, depending on the tightness of the turn, to ensure the main gear stays on the centerline.

- In the case of a G450, the nose and the outside wing tip describe exactly the same arc, but both of these are inside the arc of the tail. The pilot can be assure that the wing tips will clear obstacles if the nose does, but has no such assurance about the tail. Note that this is completely different for the G550 (and GV) where the wings describe the largest arc. In the case of a GIV, the nose describes an arc inside the wings and the tail.

Marshalling

I've noticed over the years that very few business jet pilots know how to follow a marshaller's instructions, but even fewer marshallers working for outfits who cater to business jets know how to issue marshalling instructions. Among pilots, the exceptions are those who were captains flying for the airlines, and others who operated large aircraft in the Air Force. The key thought is this: the marshaller is trying to position the main gear over where they need to be and the pilot should think of the marshaller's wands as connected to the tiller. Here's a video:

7

Landing on runway centerline

Pilots used to landing from the right seat tend to land on the left side of the runway when landing from the left seat. The easy fix is to be aware of the tendency and to remind yourself “centerline!” on every landing until the tendency disappears.

8

Judging braking effort

There is only one thing worse than braking too hard and then having to add power to make the next exit and that is not braking hard enough and running out of runway. But if you are landing on a shorter than usual runway, how do you judge distance remaining versus your normal deceleration? Try looking for the next runway distance remaining marker and multiply that by 20 to come up with a speed that gives you a gentle deceleration, by 30 for one that means you need to get serious about stopping, and by 40 for a wake up call that means you have to start worrying about the anti-skid.

Let’s say, for example, you look up and see the “3” which means you have 3,000 feet remaining.

- If you are now doing 3 x 20 = 60 knots, you are in great shape and will probably be able to coast to the end.

- If you are doing 3 x 30 = 90 knots, you need to get more aggressive with the brakes.

- If you are doing 3 x 40 = 120 knots, you really need to get on the brakes or you will have a CDM (Career Defining Moment).

9

Getting over the new captain syndrome

The Old Man, from

There I was..." 25 Years

To understand what it is to be a captain, one must first consider the lot in life a first officer has just left. Nobody describes that lot better than Ernest K. Gann, in Fate is the Hunter:

Existing in a sort of purgatory, he waits with all the patience he can muster for the day when he will no longer be a co-pilot. Until then he must mind his manners, ever balancing the obedient against the obsequious, salving his pride and temper only in his most hidden thoughts. For a number of reasons, not the least of which is his eventual promotion to a captaincy, he must observe the code of master and apprentice. The rules are fixed and catholic. I am, in all eventualities, supposed to know more than he does, a theory we both secretly recognize as preposterous.

Nobody is more aware of your status as a new captain than you. That is to say, most everyone else is not aware at all unless you do something or say something that lets them know that. A few pointers:

- Crewmembers and passengers need to know somebody is in charge and that somebody knows what is going on. That person is you. Sometimes the “cool and calm” demeanor is an act, but it is a necessary act.

- The goofy “one of the guys” persona favored by some copilots doesn’t work for a captain. Passengers don’t want to think their captain is mortal and they can be unnerved to find just how young you really are.

- Younger crewmembers are like passengers in some ways, they don’t want to think of you as incredibly young and inexperienced. You need to act the part for them too.

- Your fellow captains have been through this transition before and will be a great source of advice.

- A good captain takes crew resource management seriously. Retake your initial CRM courses again, armed with your new perspective. Remember a good captain sets the right tone from the very first crew briefing, listens to the opinions of the crew, delegates tasks fairly, and makes decisions that are easy to understand and implement.

- A good captain is human and makes mistakes. That is why self critique and crew critiques are so important.

- A good captain ends every briefing with questions that encourage crew participation and stimulate alternative views. “Do you have any questions or comments?” “Am I forgetting anything?”

References

(Source material)

Gann, Ernest K., Fate is the Hunter: A Pilot's Memoir, 1961, Simon & Schuster, New York

Gulfstream G450 Aircraft Operating Manual, Revision 35, April 30, 2013.

Stevens, Bob, "There I was . . ." 25 Years, TAB Books, 1992, The Village Press

Please note: Gulfstream Aerospace Corporation has no affiliation or connection whatsoever with this website, and Gulfstream does not review, endorse, or approve any of the content included on the site. As a result, Gulfstream is not responsible or liable for your use of any materials or information obtained from this site.