Despite what Hollywood would have you believe, panic is actually quite rare in society. People, for the most part, are not prone to wildly screaming and running about, proverbial chickens with their heads cut off. Pilots, as a subset of society, tend to be even more level headed. But if you remove the hysteria and narrow the definition of panic to "fear causing people to either become afraid to act or prone to rush to do something without thinking first," well there is evidence we have had a fair amount of that in cockpits over the years.

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-04-01

If you have ever been faced with the fear of acting, the best solution is as near as the pilot sitting next to you. "What are our options?" is a good question to start with and the discussion can unfreeze your brain. If the other pilot has gone into Zombie mode, pick up the checklist and start browsing. Doing something, even reading, can get you unstuck.

What about the opposite problem, rushing to act before thinking?

For that I recommend you adopt what we used to do when airplane engines were prone to blow up and having a cabin fill with smoke was just another day at the office. You should catalog the complete list of things that require immediate action and then practice those until you can do them without fail. "Immediate" means within a second. For me, flying a Gulfstream G450, the list is only four items long:

- Go Around / Missed Approach — If somebody pulls onto the runway as you are about to land or if you get to minimums and see nothing, you need be able to execute a go around / missed approach immediately and without error. More about this: G450 Go Around / Missed Approach.

- Depressurization — If you lose cabin pressurization you need to get on oxygen immediately. Once you've done that you can slow down a bit and get on with the pressing business of getting everyone else on oxygen and getting the airplane into some thicker air. More about this: G450 Emergency Descent.

- Weight on Wheels System Malfunction — The ground spoilers can kill you in a Gulfstream and if the weight on wheels system thinks the airplane is on the ground when it isn't, you need to disable the ground spoilers before something else in the system's logic commands them to extend. Switch off, job done. More about this: G450 WOW Fails to Shift to Air Mode After Takeoff.

- Brakes Fail on Landing — The brakes are very reliable on the G450 but it could happen. If it does, you must react quickly. More about this: G450 Braking System Failure.

So that's my list. I have the procedures down so there is no time to panic. I know that everything else gives me time (a few seconds, at least) to think things through and if I feel rushed I should tell myself to slow down.

So I don't see a reason to panic. Ever. Here are two opportune times not to panic:

- Engine Failure — If you are flying a multi-engine transport category aircraft certified under 14 CFR 25, the loss of an engine is assumed. Losing one is no time to panic. But there is evidence many pilots do.

- Stalls — Most large transport category aircraft are filled with stall warning and prevention systems that give us ample warning that our wings are getting close to aerodynamic stall. We practice with these in the simulator, treating the warning as if it is the killer event itself. But it isn't. Getting a stick shaker is no time to panic, it is time to react calmly and aggressively reduce the angle of attack. Even if you somehow find yourself in a stall, there are options.

There are other excellent times not to panic, but these are a few that seem to give some pilots problems. For these two, however, there are solutions: Preventing Panic.

2 — A good time not to panic: engine failure

1

About panic

Etymology

The Greek god Pan, from Ian Greig, Creative Commons.

There are some who say the word "panic" came from the Greek shepherd god Pan, who took delight at frightening herds of goats and sheep into sudden bursts on uncontrollable fear. That seems to fit with the current definition . . .

- a state of feeling of extreme fear that makes someone unable to act or think normally

- a situation that causes many people to become afraid and to rush to do something

Source: Merriam-Webster Dictionary

We seem to think people are predisposed to panic, as if only a hair trigger lies between serene calm and pure pandemonium. We have been told, for example, the 1938 radio adaptation of the H. G. Wells novel "War of the Worlds" led to panic across the country. Really?

[A] study by Cantril (1940) on reactions by Americans to a nationally broadcast radio show supposedly reporting as actual fact an alien invasion from Mars. The study takes the view that those who panicked upon hearing the broadcast lacked "critical ability." The behavior was seen as irrational. While even to this day this study is cited as scientific support for this view of panic, the research has come under sharp critical scrutiny. Analysts have noted that even taking the data reported at face value, only a small fraction (12%) of the radio audience ever gave even any remote credence to the idea that the broadcast was an actual news story.

Source: Quarantelli

Myth or Reality?

- We have nearly 50 years of evidence on panic, and the conclusion is clear: people rarely panic, at least in the usual sense that word is used. Even when people feel "excessive fear"—a sense of overwhelming doom—they usually avoid "injudicious efforts" and "chaos." In particular, they are unlikely to cause harm to others as they reach for safety and may even put their own lives at risk to help others.

- Panicky behavior is rare. It was rare even among residents of German and Japanese cities that were bombed during World War II. The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, established in 1944 to study the effects of aerial attacks, chronicled the unspeakable horrors, terror and anguish of people in cities devastated by fire storms and nuclear attacks. Researchers found that, excepting some uncontrolled flight from the Tokyo fire storm, little chaos occurred.

- An enormous amount of research on how people respond to extreme events has been done by the Disaster Research Center, now at the University of Delaware. After five decades studying scores of disasters such as floods, earthquakes and tornadoes, one of the strongest findings is that people rarely lose control.

- Consider, also, the tragic flight of American Airlines 1420. In Little Rock, Arkansas, on June 1, 1999, Flight 1420 tried to land in a severe thunderstorm. As the pilots approached, they couldn't line the plane up with the runway and by the time they righted the craft they were coming in too fast and too hard. Seconds after the plane touched down, it started sliding and didn't stop until after lights at the end of the runway tore it open. The plane burst into flames, and 11 of the 145 aboard were killed. The National Transportation Safety Board's "Survival Factors Factual Report" has more than 30 pages of survivor testimony. Most survivors who were asked about panic said there was none. Instead there were stories of people helping their spouses, flight attendants helping passengers, and strangers saving each other's lives.

Source: Clark

More about this: American Airlines 1420.

- The same message rises from the rubble of the World Trade Center. Television showed images of people running away from the falling towers, apparently panic-stricken. But surely no one would describe their flight as evincing "excessive fear" or "injudicious effort." Some survivors told of people being trampled in the mass exodus, but those reports are unusual. More common are stories such as the one from an information architect whose subway was arriving underneath the Trade Center just as the first plane crashed. He found himself on the north side of the complex, toward the Hudson River: "I'm looking around and studying the people watching. I would say that 95 percent are completely calm. A few are grieving heavily and a few are running, but the rest were very calm. Walking. No shoving and no panic." We now know that almost everyone in the Trade Center Towers survived if they were below the floors where the airplanes struck. That is in large measure because people did not become hysterical but instead created a successful evacuation.

- An alternative to panic as an explanation of how people respond to disasters is the idea of failing ungracefully. In software engineering a system that fails "gracefully" can take discrete breakdowns without crashing the whole computer program. In the present context social relationships and artifacts (walls, machines, exits, etc.) no longer function as they were designed.

Source: Clark

It seems the stereotypical view of panic — people running about, screaming, throwing loved ones over board in a blind attempt at self preservation — that is extremely rare. But the definition of the word — a fear that makes someone unable to act or think normally and to cause them to rush to do something — that fits what we see in some aircraft mishaps. There are examples of panic on flight decks.

2

A good time not to panic: engine failure

One of the few drawbacks of training exclusively in a simulator is pilots can compartmentalize their emergency procedures for the box and their normal procedures for the airplane. We see case after case of pilots who can ably handle an engine failure in a simulator failing to do so in the airplane. I must admit to being in the generation where we practiced these things in airplanes. So when it happened to me in real life (three times on takeoff and twice that many when en route), it was not really a big deal. So let's make this clear for anyone who has never had an engine failure in an actual airplane . . . if you've got more than one engine, losing one is not a time to panic.

As of 11 March 2015, the Aviation Safety Network database shows 17 occurrences of wrong engine shut downs in the last 69 years. There were just as many in the last half of that period as the first. Here are a few of the more recent ones.

Examples of engine failure panic attacks

1989 Jan 8 — Case study: British Midland Airways 092

1992 Apr 22 — A de Haviland DHC-6-200, N141PV, departed Perris, CA after having been serviced with contaminated fuel. Immediately after takeoff the right engine lost power. The NTSB findings: The pilot in command's inadvertent feathering of the wrong propeller following an engine power loss, and the failure of the operator to assure that the pilot was provided with adequate training in the airplane. [Source: NTSB LAX92MA183]

1995 Jul 19 — A privately owned DC-3 was crashed after its right engine failed and the left engine was shut down. Only the pilot in command was killed. [Source: NTSB Narrative NYC95FA167]

1995 Dec 5 — A twin-engine Tupolev 134B-3 operated by Azerbaijan Airlines crashed during its initial climb after the left engine failed and the crew shut down the right engine. The copilot was flying when the left engine failed and countered the yaw and roll just as the flight engineer reported that it was the right engine. The captain assumed control and ordered the right engine shut down. The engineer shut the engine down, realized that it was the operating engine and attempted a relight. 52 of the 82 on board were killed. [Source: Aviation Safety Net]

2001 Aug 29 — A twin-engine CAS CN-235-200 operated by Binter Mediterraneo crashed on approach to Malaga Airport, Spain. During the approach a left engine fire light was noted by the crew. They ended up shutting down both engines and descended into the approach lights, killing 4 of 37 on board. [Source: Aviation Safety Net]

2009 Sep 24 — Case study: SA Airlink 8911

2015 February 4 — Case study: TransAsia GE 225. Shutting down the wrong engine, not flying the airplane [Source: Aviation International News, March 2015, page 48]

- Flight record data from the TransAsia ATR 72-600 that crashed in Taipei on February 4 indicates that the right engine flamed out soon after takeoff, followed by a left-engine shutdown, according to a preliminary report released by Taiwan's Aviation Safety Council. A pair of Pratt & Whitney Canada PW127M turboprops powers the ATR 72-600.

- Speaking in Taipei two days after the crash, safety council Thomas Wang noted that "for some reason the Number 2 (right) engine autofeathered" 37 seconds after takeoff, as the airplane climbed to 1,200 feet.

- According to the report, a master warning associated with a right engine flameout procedure message on the display unit sounded. Twenty-six seconds later the pilots progressively retarded the left engine to flight idle, the data suggests, then set the left engine condition lever to the fuel shutoff position. Several stall warnings sounded over the course of six seconds. The flight crew then declared an emergency and reported an engine flame-out. Roughly 30 seconds later they called several times for an engine restart, and the recorded parameters, in fact, indicate a restart of the left engine. Finally, some three minutes after takeoff, the master warning sounded and the CVR recorded an unidentified sound. Less than two seconds later, both recorders stopped recording.

- Video footage of the event taken by a motorist driving on an elevated roadway in Taipei's Nangang District show the 70-seat turboprop banking sharply left, barely missing an apartment building and clipping with its left wing the top of a taxi traveling on the overpass before diving into the Keelung River. Rescue crews on the scene minutes after the crash pulled 15 survivors from the wreckage. By February 12 search crews had recovered the bodies of all 43 people who died in the crash.

How to survive an engine failure on a multi-engine airplane

A transport category airplane certified under 14 CFR 25 is designed to fly with the critical engine out, so if anything kills you, it is probably you. The two most likely ways for that to happen is when you (a) apply the wrong rudder, or (b) shut down the wrong engine. Too many pilots think of an engine failure as a macho test of speed to see who can get the rudder in so fast that other pilots don't even notice the yaw. If the airplane doesn't have time to yaw, you aren't doing it right. Now all of my engine failure experience has been in two or four-engine jets. You should practice this in a simulator, but this has always worked for me:

- Allow the yaw to develop, this gives you time to think and will provide a needed clue as to what is going on.

- Level the wings with ailerons, and unless climb performance is critical, do not rush in with rudder.

- Note which hand is low (if you have a yoke) or which way the hand is pointed (if you have a stick). This is where your foot will need to be to correct the yaw. "Step on the low hand" as well as "step on the ball" of your slip indicator. Do not stomp on the rudder, you could lose the tail. Your application should take at least a second, two would be better.

- Wait until you are at least 1,500' before shutting down engines.

- Make an engine shutdown a CRM process that includes a "wait and see" step:

- Put your hand on the throttle you intend to pull and ask the other pilot to confirm, "I suspect number one is failed, I have my hand on the number one throttle. Confirm?"

- Pull the throttle to idle and wait. Verify the situation didn't get worse.

- Announce the throttle pull reaction and your intention to shut down the engine, get validation. "I've pulled number one to idle, the yaw hasn't changed and we are still climbing. I am about to shut down number one. Confirm?

I've lost engines at V1 three times, en route another six times. I've never had one that required an instant reaction and I let one burn for about three minutes before getting around to shutting it down. Of course your airplane might be different and I suggest you try my "step on the low hand" technique in the simulator. There may be times when getting it done ASAP might be the right thing to do, but I think I will recognize that if it ever comes. For now, my approach is to be methodical about engine failures.

More about this: Asymmetrical Thrust.

3

A good time not to panic: stalls

If you have been flying for less than thirty years, you may have never stalled an airplane requiring a type rating. We have generations of pilots raised in simulators that make that kind of training unnecessary. That is probably a good thing, but it may also further the "simulator is for abnormals, airplane is for normals" mentality that creates panic when it happens in the airplane. We've also had decades of stall training that emphasized minimal loss of altitude when in fact the clarion call of any stall is to reduce angle of attack. Plainly stated, you must quickly and aggressively push forward to unload the wing and resume flying.

Every few years there is another accident caused by professional pilots either reacting incorrectly to a stall or placing a perfectly good airplane into a stall. The official blame usually has to do with poor pilot training but in some cases the pilot was trained repeatedly in a simulator and failed to apply that training in the airplane. Simulator training in the past was meant more to pass check ride altitude standards than to stress the need to break the stall above all else.

Examples of Stall Related Panic Attacks

1994 January 7 — Case study: United Express 6291

2004 October 14 — Case study: Pinnacle Airlines 3701

2009 February 12 — Case study: Colgan Air 3407

How to survive an aerodynamic stall

Your prime directive when faced with an aerodynamic stall is the get the wing flying again and that means you have to decrease the angle of attack. The best way to do that is to decrease pitch and that is going to take a conscious push forward on the yoke for most aircraft. Don't play around, give it an aggressive push. Try this in the simulator on approach at an MDA around 500 feet AGL: get the airplane to its initial stall warning and recover with a good healthy push. See how much altitude it takes. Not much, eh? Now try that again with the next level of stall warning, perhaps the stick shaker. And that leads us to . . .

Do not override the stick pusher. Let it do its job, break the stall. More about this: Low Speed Flight and Stall Recovery.

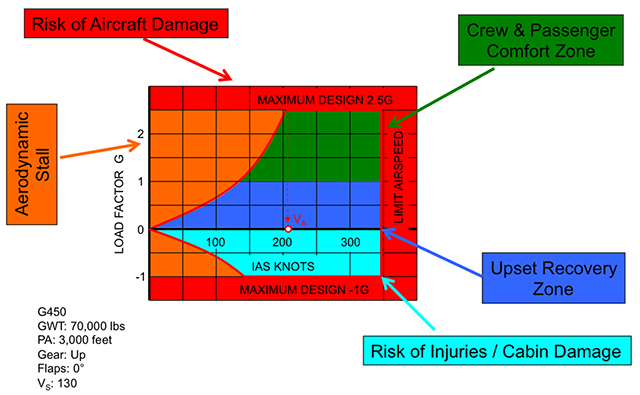

Not all stalls happen low to the ground or with the nose just above or below the horizon. Remember that stall speeds are determined by aircraft weight, altitude, and G-loading. Yes, you can lower your stall speed significantly by flying the airplane at less than 1-G.

More about this: Unusual Attitudes & Upset Recovery.

4

Preventing panic

The best way to avoid panic in a given situation is to experience that situation a few times. One of my rules of life: "A practiced calm will serve you well." Practice calm? Yes. After a while, you will find the ability to remain calm in one situation (a car accident, let's say) transfers to others. So how about our two examples of when not to panic?

- Engine Failures — If you have never had an engine quit in flight, never seen an engine fire warning in an airplane, or never had to land with less than every engine operating, you need to get that experience. How? Find a multi-engine flight school at your local airport and tell them what you need. You want a multi-engine instructor to take you up, let you shut an engine down and fly for a few minutes with one not turning and your hands on the ailerons and your feet on the rudder to keep the airplane flying straight. And then restart the engine and press on. Trust me, you need to do this. It will make you a better pilot, less prone to panic when it happens when you least expect it.

- Stalls — If the only airplane you've ever stalled was a primary flight trainer like a Cessna 150 or a Piper Tomahawk, you need to get something in the high performance category and at least get into a moderate stall buffet. As long as you are doing that, you probably ought to get some upset recovery training. The simulator is not good enough.

References

(Source material)

Air Training Command Manual 51-3, Aerodynamics for Pilots, 15 November 1963

Clark, Lee, "Panic: Myth or Reality? Contexts Magazine, 2002, pgs. 21 -26.

NTSB Narrative NYC95FA167, Douglas DC-3, N54NA, July 19, 1995 in Independence, NY

NTSB Probable Cause, LAX92MA183, de Havilland DHC-6-200, N141PV

Quarantelli, E. L., "The Sociology of Panic," University of Delaware Disaster Research Center, Preliminary Paper #283, 2001.