This story has nothing to do with flying airplanes and very little to do with today's military. It is a testimony, I suppose, to how screwed up one particular base was.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-03-31

Loring Air Force Base was part of the cold war build up and part of an attempt to keep the Maine congressional delegation happy. The base quickly became a liability because it was too close to the Atlantic coast and the odds of getting airplanes airborne before Russian cruise missile obliterated the place were going from slim to none. The Air Force tried in vain, every year for ten, to close the base. It wasn't until 1994 the place was put out of its mystery. I was there for 20 months, twenty-two days, and twenty hours.

Second Lieutenant Fred Neavis was a brand new KC-135 navigator, fresh from Combat Crew Training School where he learned the ins and outs of navigating the massive four-engine aircraft. He also learned combat tactics, Strategic Air Command rules and regulations, and a host of security protocols. He was introduced to SAC's concept of duress. Duress meant you were being coerced by a foreign enemy agent to do something against your will, and SAC had ways to combat against that.

"Duress code of the day," the speaker behind the podium said, "is Apple." The slide on the screen changed and the weather for today's mission was projected. Everyone in the audience took a mental note of the duress word and shifted their thoughts to weather.

Neavis's KC-135 would be the tail end Charlie of an twelve ship formation of bombers and tankers departing Loring Air Force Base, Maine to attack imaginary targets in Wyoming. The exercise was part of the wing's Operational Readiness Inspection. The ORI was the wing's most important evaluation as a combat unit and would determine the promotions of almost everyone on base. The circular error probable - how close to the target the simulated bombs got - was most of the grade, to be sure. But everything was evaluated.

Second Lieutenant Neavis had been on active duty for nearly two years. Navigator school, land survival training, water survival training, and prisoner of war training ate up the first year. KC-135 navigator school was another six months. Now, with nearly half a year at Loring, flying the tedious five-hour missions no longer induced the violent air sickness. Fun it wasn't. But vomit inducing it ceased to be.

As the last airplane in formation, Lieutenant Neavis's job was to simply back up the lead navigator's accuracy while compiling the necessary paperwork to satisfy ORI inspectors that he did just that. There weren't any inspectors on board the tail end tanker, but navigation and celestial logs would be turned in and combed over by the inspectors. Up front, the copilot would be working the high frequency radios to copy SAC coded instructions. It was up to the navigator to decode the instructions.

Second Lieutenant Neavis's copilot was a second lieutenant straight out of pilot training. Lieutenant Haskel was your typical 22-year old copilot, more interested in flying the aircraft than actually paying attention to the ORI. At least he was competent. After the first hour he had the list of fifty alpha numeric codes from the HF and handed the list to Neavis. Of course Neavis would be too busy to see them until the refueling was completed.

The ORI was over for Lieutenant Neavis's airplane when they landed that day. Right about then the first bomber was dropping a concrete bomb on a target range in Wyoming. The bomb missed by almost a mile. A "shack," or bull's eye, would be measured in feet. "Almost a mile" was not good. The wing's B-52's were tasked with hitting targets deep inside Russia to take out opposing bombers and missile sites. Fortunately, about half the bombs dropped during the ORI were good.

Most of the wing's grade would be based on how close those bombs came to their targets. But none of that was Lieutenant Neavis's problem. After the flight his only remaining task was returning his bag of secret codes back to the command post. As the crew bus weaved its way from the flight line, the pilots were consumed talking about pilot stuff and the boom operator sat silently alone, probably asleep. The guys in front and the guy in back were done; only the guy in the middle still had responsibilities. It was just below freezing outside and the heavy flight suit coat was too much for the temperature inside the bus, but the lighter summer coat would have been too little for the cold outside. A bead of sweat formed on Neavis's brow as he jumped out of his seat and headed for the door. If he spent too much time returning his canvas bag of secrets, the pilots would unload on him for keeping them from the bar, or wherever it was that pilots went after flying.

Outside the bus the bead of sweat froze instantly to his eye brows and the wind knocked whatever breath he had inside his lungs through his mouth and into the brisk, Maine air. Neavis opened the heavy door to wing headquarters and took the stairs down to the command post by twos. Rounding the last hallway corner to the command post, he spotted an unfamiliar man in a brown trench coat. The man opened his coat and pulled out a gun.

His copilot carried a gun, but that didn't do Neavis any good now. Lieutenant Haskel would be able to defend his crew bus, but Neavis had nothing more than the parachute knife strapped to his leg. How did that saying go?

Never bring a parachute knife to a gun fight.

The gun was unlike any he had seen before. It was painted white and had a red stripe. "Lieutenant," the assailant said, "this is an ORI simulation. I am a Russian spy and I want you to get me into the command post. Simply react as you would if I were a real Russian spy with a real Russian gun."

Neavis stood, motionless, wondering what to do.

"Now," the no longer mysterious figure continued in a contrived Russian accent, "comrade, put your hands down. Do not attract attention. Go to command post. Tell the American capitalists you are returning your bag of secrets. I will do the rest."

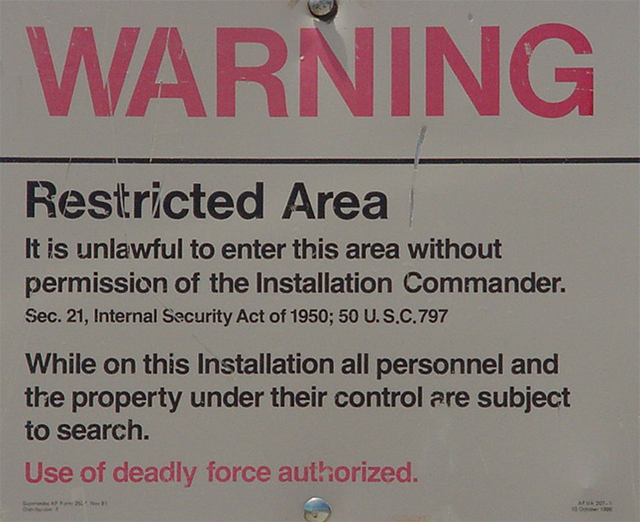

Neavis walked towards the command post, which was guarded by a heavy steel door with a window in its center. The center window was lined with a heavy steel grate and covered by a sliding pane of steel. To the left there was a phone. In front of the door was the standard warning to intruders: the use of deadly force was authorized to any who dared breach the security of that bullet-proof door.

Neavis's mind raced. What was the duress word for the day? Oh yes. He picked up the phone. "This is Lieutenant Apple, requesting entry to the command post."

"Roger," the voice answered. The door buzzed, a lock clicked, the door unlatched open and moved ajar a few inches. Neavis quickly slammed the door shut before the ORI goon could leap in. The inspector scribbled on a note pad but otherwise stood his ground.

Neavis picked up the phone again. "This is Lieutenant Apple Neavis. I am requesting entry to the apple."

"Roger." The door buzzed, a lock clicked, and the door unlatched once more. Again Neavis slammed the door shut. The inspector shook his head and scribbled some more.

Neavis picked up the phone. "This is Lieutenant Fred Neavis on Sortie one-oh-nine. I am under duress. The duress word for the day is apple. I am using the duress word, apple, because I am under duress. Do you understand?"

"Roger." The door opened again. The inspector thrust his foot through the door.

"Lieutenant," the inspector said, "you've done all you could. You can leave now."

Lieutenant Neavis nodded and turned to leave. Behind him he heard the inspector yell, "this facility is now blown up. You are all casualties."

A week later, at the base theater, the wing sat and listened to the ORI inspectors detail Loring's performance. "Bombing - SAT," the first slide reported. Of twenty attempts, the bare minimum reached their targets.

"If the minimum wasn't good enough," the saying went, "it wouldn't be the minimum."

Each slide reported that Loring was meeting the minimum. The last slide, however, was on security measures. "UNSAT" in this category, everyone knew, would sink the wing. And it did just that.

For Lieutenant Neavis, life kept going uninterrupted. The base got a new wing commander, the command post got a new boss, and Loring just kept going. A minimum performance wing doing the minimum to get by.