The Air Force Boeing 747 that I flew had a few missions over the years and what they do today has nothing to do with what they did when I flew it. One of our missions was for during nuclear combat and that earned it the name, "America's Doomsday Plane." Rightfully or not, the name seems to have stuck.

— James Albright

Updated:

2019-02-18

The "Doomsday Plane" moniker didn't really impact us and I don't think any of us pilots really used it. But we recognized it when we heard it and the repercussions were never good. Such as during . . .

Lieutenant Colonel Alton Gee had a saying for everything and it took a few years to learn them all. As a fellow collector of sayings I listened to each of his and added the ones I liked to my lexicon. One that I passed on was: “You can screw up, just make sure you find a bigger screw up to follow you.” It didn’t seem particularly helpful – after all, how about “just don’t screw up” as an alternative? – and I really didn’t understand it. Until the week of my three violations.

First, an aside: Our 747 was sometimes called “The Doomsday Plane,” because as the President's back up aircraft, ours had to survive anything, even the war that was everyone’s nightmare. That meant we could never find ourselves with too little fuel to do the mission and we usually took off with more than we could land with. When that happened, we would end up in a holding pattern someplace until we were light enough to land.

Oh yes, another aside: We had special codes to bully our way around the air traffic control system, something we pilots called our “Get Out of Jail Free” cards. Sometimes we had to get to the front of the line, sometimes we had to close runways, sometimes we had to do things the FAA rulebook said simply could not be done. Of course sometimes Cleveland Center would get upset or Dulles Tower would deny our requests. No problem, say the code word and everything is better.

So there I was, in command of the back up airplane somewhere in the Midwest, worrying about the weather. The ceilings were coming down and the snowfall line was about a hundred miles to our west creeping eastward. The same line had appeared a few times the days before, only to peter out. Waiting it out meant we would save the fuel spent flying looking for another airport to hole up at. The crew and passengers hated the bug out routine, but everyone understood the price of getting caught would be too high. Nobody wants to call the White House and say the backup was grounded.

Oh yes, it was five in the morning, Friday morning. I was huddled over the radar scope at the Grissom Air Force Base weather shop, our chosen refuge for the week. By today’s standards it wasn’t much of a radar, but it clearly showed the line of weather marching its way to Indiana. I picked up my portable radio – no cell phones back then – and called the airplane. “We’re going, wake everyone up.”

I hopped in the car provided by the base and sped down the taxiway to the airplane. I hit 70 mph before the radio announced to all on the airfield, “the airport is closed all operations give way to the 747.” As I neared the airplane I saw our passengers and off duty crewmembers running to the airplane while the ground crew busied themselves disconnecting the myriad of electrical, water, and pneumatic umbilical cords. I saw the puff of smoke behind engines one and four, our crew chiefs starting the outboard engines in anticipation of my arrival.

I parked the car at a wing tip and jogged to the air stairs as fellow crewmembers cried out ahead, “make a hole, pilot coming.” The seas parted and I ran up the stairs, turned right to the nose. “Make a hole,” I heard with every turn and I had nobody in front as I hit the spiral stair case to the top floor. Through the cockpit door the navigator was in his seat, the flight engineer was standing to one side as I hopped in the pilot’s seat, front left. The crew chief in the right seat looked at me and I nodded. He jumped out and the copilot took his place.

“Flight deck to all sections,” I heard the engineer say as I strapped my headset into place, “report.”

“Comm section ready,” the first reply came. “Security ready,” came next, followed by the next and the next after that. Once done, the engineer chimed in last over the same channel, “Pilot, engineer, all sections ready.”

“Ground crew,” I said, “come on up, report ready for taxi.”

Within seconds I got the reply, “ground crew on board, sir, stairs off the ground, clear to taxi.”

I pushed the outboard throttles and aimed the airplane to the end of the runway. “Turning two and three,” the engineer said. The copilot configured the flaps and flight director while telling tower we were clearing ourselves for takeoff. By the time I got to the runway the engineer finished with, “pre-takeoff checklist complete.”

We were airborne five minutes after I made the “we are going, wake everyone up” call.

Meanwhile, a hapless duty officer in the control tower was fighting with a safe trying in vain to find our call sign in a book of classified call signs. Today we were “Gumbo 35,” just a random word with random numbers designed to hide our true identity to anyone listening in. These call signs remained classified until we actually used them on the radio but the tower officer either didn’t know he could simply take the call sign we gave him over the radio or got distracted by the safe and failed to pick up the phone and notify Indianapolis Center that a Boeing 747 was about to pop up on the radar screen flying way too fast heading straight for Washington, D.C.

“Indianapolis,” the copilot announced on center’s frequency, “Gumbo three five is passing two thousand feet climbing to flight level two five zero.”

“Gumbo three five,” the center controller replied, “I see you on radar but I don’t know who you are. What are you doing in my airspace without a flight plan?”

The copilot tried to explain, politely, that we were now passing 5,000 feet and heading straight to Washington and if he would like us to join an airway to make life easier we would be glad to do so. The copilot was fairly new to all of this but did just as he was trained and showed an abundance of patience and civility. Sometimes that doesn’t work.

“Gumbo three five,” center said, “you are mucking up my airspace so I suggest you turn around and exit my airspace right now. Not only that, I want you to give me a call on the ground.”

With that the copilot gave me a pleading look, “are we being violated?”

“Violation?” the navigator asked. Only the engineer smiled, knowing what was to come.

“Indianapolis Center,” I said over the frequency, “I need your supervisor on the frequency right now.” I then gave him the code word. “You need to clear a path in front of us and do it right now. I will call you when we land and I suggest you have your chief counsel on the line when I do.”

Two hours later I was on the ground talking to the controller and accepting his apology. The copilot listened intently and asked me for a copy of the air traffic control regulation covering our aircraft. All of our aircraft commanders – Air Force speak for the airplane captain – kept a copy nearby at all times. The navigator, for his part, wanted to know about the “being violated” part. I explained that most pilots believed the “call me on the ground” meant the air traffic controller would cite you for violating a federal aviation regulation and that almost always resulted in the pilot losing his or her license. We, of course, were immune to that as long as we were operating within our rule book and issued the code word when needed.

The whole code word thing wasn’t something that happened a lot, we usually got our way without it and, to be honest, I had only used it twice before.

Before we got to D.C. we got new marching orders to pick up a White House type in a small airport someplace from Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. We showed up in the pattern with the Marine Helicopter waiting for us at the end of runway 26 and on the other end a USAir flight on short final. We knew that as soon as that airplane landed the tower would close the airport and give us the airspace. I set up for a high speed pass at 500 feet, timing my acceleration to end up over the runway as the USAir flight pulled safely off. But it didn’t happen that way.

“USAir one thirteen going around,” the airplane said, “it’s a bit gusty, request a visual pattern to try it again.”

“USAir one thirteen,” tower said, “negative, contact departure one point three three.”

“Why do we gotta do that?” they asked, “we can do this visually.”

“Negative,” tower said, “airport is closed for ten minutes. You can enter a right downwind and do three sixties until we open if you prefer.”

He preferred.

I lined up on the runway and flew overhead, sighting the helicopter right where it should be. We pulled up left, on a left downwind, left base, final, and landed. At the end of the runway the passenger left the helicopter and boarded.

“Who is that?” USAir asked on tower frequency, “Why are we holding while some government big shot monopolizes the runway?”

Tower said nothing.

“Ready for takeoff,” the copilot reported to tower.

“Cleared for takeoff,” tower said.

As I dipped the right wing below the horizon and sped off, I heard from USAir. “I don’t know who you think you are, but I have a hundred and forty five paying passengers on board and they don’t like waiting for you government big shots. I’m calling my congressman and as far as I am concerned, you need to be violated.”

“Like we never heard that before,” the navigator laughed.

A day later we were in Omaha and I was staring at another radar scope. “Let’s go.”

We were airborne heading back to Indiana with too much gas to land. No worries: half our pilots would enter a holding pattern until they burned off the fuel, the other half would ask the passengers if they minded doing a few approaches to low approaches, just to give us pilots something useful out of the time. Since these practice approaches burned extra fuel they got us on the ground sooner and most passengers were all for that.

For months I was toying with the idea of shooting these approaches to my alma mater, Purdue University, just thirty miles to the west. Why not? Why not, indeed.

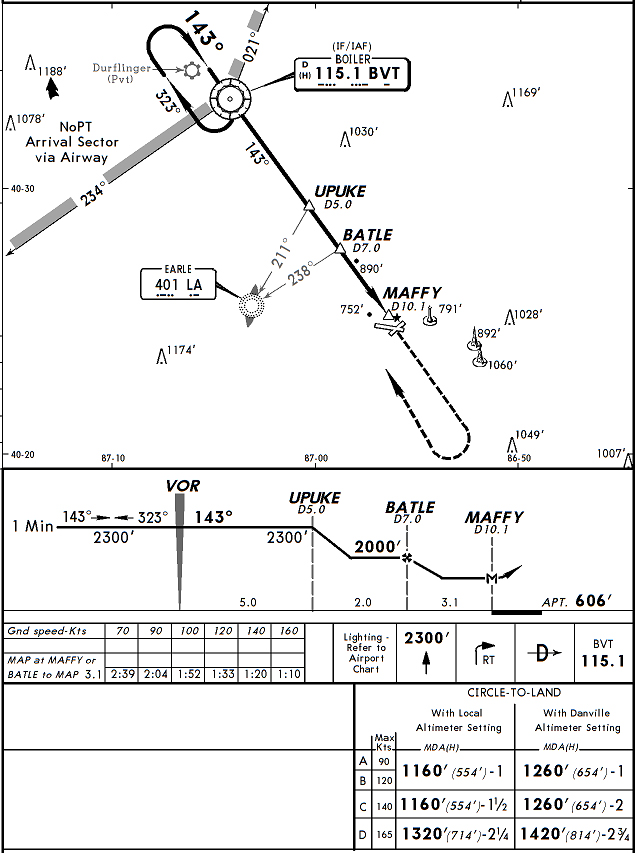

The VOR-A approach to Purdue University Airport starts north of the airport and for our size aircraft allows maneuvering 2.3 nautical miles around the airport in a sweeping right turn to line up with the runway. That turn, while maneuvering for runway 28, takes you right over the football stadium. Oh, did I mention this was a Saturday?

Of course I didn’t know there was a home game going on, but I am told the players on the field stopped and pointed skyward as a Boeing 747 flew overhead at 714’ above. A 747 flying overheard at that height is quite an impressive sight, especially when it says “United States of America” on the side easy enough to read from the ground. But then the football players stopped to look. And so did the 62,500 people seated at Ross Aide stadium. How many were watching on ESPN, of course, is pure speculation.

The approach went well and Purdue Tower thanked us for the fly by. We showed up at Grissom where the ground controller said Purdue Tower wanted a call.

“Another violation?” the navigator asked.

I called; they just wanted to thank me again.

The next day the local paper featured us: "Doomsday Plane Buzzes Purdue."

I called the paper, without revealing my connection to the aircraft, and asked what the big deal was. They said, “oh no big deal, there was just a noise complaint and a few people at the Football stadium just wanted to know what the airplane was doing. As it turns out it was just a training approach to the local airport. No big deal.”

I filed the entire incident away under the “fun but not advisable” category. The next day we were back home and I entered the squadron with the copilot and navigator ready to turn in our week’s paperwork. Behind me I heard my name with the all-too-familiar “you are in trouble” tone.

“Albright,” I heard the squadron commander bark, “get in here, you’ve been violated!”

“What?” the navigator said, “again?”

As it turns out the squadron commander meant we had violated noise abatement procedures – we had not – but now wanted chapter and verse about the “other” violations.

I was grounded for a week while half the squadron thought me an idiot for being caught flying a low altitude approach over a football stadium and the other half thought I was a genius for flying a low altitude approach over a football stadium.

I remained in limbo for one week, until the next Sunday, one of our other pilots did the same thing someplace over Florida. It wasn’t exactly the same thing. He flew over a pro football game being broadcast on network TV.

The brass forgot all about me and zeroed in on the next screw up.

“You can screw up, just make sure you find a bigger screw up to follow you,” Alton said.