At the ripe age of 28 I was an Air Force instructor pilot flying a Boeing 707 five miles from where I grew up in Hawaii. My commitment to the Air Force for earning my pilot's wings was about to run out and I would, for the first time, be eligible to become an airline pilot. That is, after all, what Air Force pilots did back then; the vast majority of airline pilots in those days came from the U.S. Air Force and Navy. Just as I was starting to formulate a plan, the head of pilot hiring at Aloha Airlines called up out of the blue and said I was guaranteed a job, the interview would just be a formality. As if fate had a hand in this, the Air Force offered me the chance to fly a Boeing 747 and my decision was made. I imagine many of you have never heard of Aloha Airlines because they went out of business years ago.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-07-10

Of course that is what many airlines do, they go out of business. But some don't and there certainly was no job security as an Air Force pilot. With the end of the Vietnam War followed by President after President trying to extract what became known as a "peace dividend," the Air Force didn't need pilots. We each had two tries at each promotion and if we didn't make that, they showed us the door. That happened several times for my year group. Many of my peers were shown that door after 16 years of service: no pension, no nothing.

An Air Force pilot's first shot at any kind of pension happens after twenty years and that is when I made the jump to corporate aviation. While living in Houston, Texas attending a high school event for my son, I met someone from Continental Airlines. Yes, they were hiring and I would be a shoo-in. Ever heard of them? For that matter, have you ever heard of Compaq Computer? That's who I was working for when I suddenly found myself unemployed.

Be it a promotion passover, a company going out of business, or the proverbial airline furlough, we professional pilots have to get used to the "What am I going to do now?" question.

2 — Plan A: figure it Out when it happens

3 — Plan B: find a hobby that grounds you

1

The no other plan, plan

We pilots tend to be an optimistic lot and the normal progression from the guy at the bottom (CFI or commuter first officer) on the way up can be exciting and intoxicating. So much so, in fact, that the thought of doing anything else is abhorrent. Who wants a J - O - B when you can be flying instead? I've known a few pilots over the years that didn't have a plan, only a single-minded goal. That works if you are lucky. But how can you predict luck?

I met Harrison "Don't call me Harry" just before he realized his childhood dream of becoming an airline pilot. He grew up in a small town just underneath the traffic pattern at Cahokia Airport, better known as St. Louis Downtown Airport these days. He got his first job at that airport pumping gas into Cessnas and eventually ended up as the senior Certified Flight Instructor teaching others to fly those airplanes he used to wash in exchange for flying lessons. I was an Air Force pilot at the time and delivered a Gulfstream III to a maintenance facility in Cahokia. That company went on to specialize in Gulfstreams, but in 1994 we were their first large jet. Surveying the airport, it seemed our GIII was the biggest airplane on the airport that day.

It was the same day the Cahokia flight school was having a party for Harrison. He had just been hired by Trans States Airlines, a commuter airline flying small turbo props out of St. Louis Lambert International. He dropped by to look at our airplane and I gave him a quick tour. We chatted briefly and he told me that the commuter was just a stepping stone to his real ambition: flying jets with Trans World Airlines. He would be a TWA pilot. Harrison was full of energy, had a quick smile, and was keenly interested in all things aviation. I believed that he would indeed make it to TWA.

Six years later I was stationed at Scott Air Force Base, just east of St. Louis, getting close to the twenty-year point, and was entertaining the thought of flying for Trans States Airlines until I decided what I really wanted to do. They offered to put me in the left seat of one of their aircraft, all I had to do was interview. The guy doing the interview recognized me immediately and after he spoke I recognized him. It was Harrison.

He explained that he was building hours and experience until he had enough for TWA. Many of his peers had already made the jump to United, American, and Northwest. I asked him what was keeping him from doing that too. "Not interested," he said. Harrison had his heart set on TWA and nothing would detract him from that goal. He still had that gleam in his eye. He was in the right place to make his dreams come true.

Of course I ended up in corporate aviation instead. I didn't give Harrison a second thought until TWA got bought out by American Airlines in 2001. A friend of mine at American told me that the pilot "rack and stack" put most of the TWA pilot list at the bottom of the American line number list. "So you could be a 30-year TWA captain one day and an American first officer on reserve the next?" I asked. "Yeah, isn't that great?" He had the complete list so I asked. Harrison's name was on the list, almost at the end. A year later, most of the former TWA pilot pool was on the street.

Five years later I was back in Cahokia dropping off yet another airplane to the same Gulfstream maintenance facility when I spotted Harrison walking around yet another Cessna with a high school student in tow. He recognized me and I offered him a tour of another Gulfstream, this time a GV, but he wasn't interested. He said that after he was furloughed, he got a job driving semi tractor trailers for a few years, waiting for American to recall him. He was making more money than he had at TWA or American, got married, and was getting comfortable. "But I missed the flying, so here I am," he said, without the smile I had come to expect from him. "Besides, being an airline pilot isn't flying, it's computer programming. This," he said, pointing to his Cessna, "this is real flying."

Years later American finally recalled their last furloughed pilot and I asked my friend there. "No," he said, "I don't see his name on our list."

I like to imagine that Harrison is still at Cahokia, still giving high school kids their first look at aviation. He will have lots of war stories about a life "out there" in the real world. But I suspect he will always be a little bitter about the airlines.

2

Plan A: figure it Out when it happens

Flying airplanes requires an amount of skill that often translates well to other endeavors. Put another way, talents in some areas of life translate well to flying airplanes. I think most pilots fall into this category and while they don't have a plan for if and when the flying gig disappears, they know they will come up with something.

As long as I've known Ollie, he has been good with his hands. He liked to tinker on his own, but he never once considered earning a living in the trades that employed generations of his family in and outside of the Boston city limits. His father was a general contractor and his older brothers included a plumber, an electrician, and a carpenter. Ollie wanted something else. As the Vietnam War was at its height, he figured out "Uncle Sugar" would pay his way through college and then he would just roll the dice when it came to that war. Ollie played the hand that was dealt him perfectly. He got his commission as an Air Force second lieutenant, went to pilot training and earned his wings the day the war ended. Four years to the day after getting those wings, he returned to Boston determined to never again leave the Bay State.

The airlines were not hiring but corporate was, so he started flying charter out of Bedford, Massachusetts. It was perfection. But in 1980 the job went away and nobody was hiring. Ollie's job was a victim of rising oil prices that was compounded by a nationwide recession which hit Boston particularly hard. The only job to be had was as a roofer. It was back breaking work that paid nearly as well as his flying gig, but Ollie knew it was a life he couldn't bear much longer. After a year he managed to find a job on a house framing crew and learned the trade well enough to add many skills that made him quite the handy man for friends and family for years to come. Of course the economy came back and Ollie returned to the cockpit until the next big recession. For the second round he managed to find a job in a furniture factory and his skills actually resulted in a pay raise. When a flying job appeared he gave serious thought to a making his career change permanent, but the lure of a cockpit seat was too strong.

Ollie never left aviation again until, at age 60, his back finally gave out and he decided to just quit working. He didn't have much saved but managed to get by until at 62 and a half, he started collecting social security. Today he talks fondly of a lifetime of experiences and has few regrets. He has a close circle of neighborhood friends and the highlight of his week is the Saturday poker night at the town lodge. He introduced me once as a "hot shot Air Force pilot" and I returned with "but I've never flown a real war plane like Ollie." (He flew the B-52 bomber.) His friends were stunned. They had no idea he was ever a pilot.

3

Plan B: find a hobby that grounds you

We pilots tend to be resourceful and the "I'll cross that bridge when I come to it" plan seems to be as good an option as any. Except that it isn't. When you are forced to come up with options, they can be less than optimal. Having something outside of aviation can provide you the calm you need to ride out the uncertainty. And as importantly, it gives you a direction to head when the current path inevitably comes to an end

I first met Keith Rumohr when he showed up to take my place as our wing's flight safety officer at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii. He followed me to the next squadron and I eventually followed him to corporate aviation. He has seen a lot of pilot turmoil through the years and he never seemed to be particularly fazed by any of it. I had to wonder what gave him that sense of calm. Every now and then we would have a retirement or going away party, and if Keith was a fan of the guest of honor, he would present them with a very nice wood carving.

Years later I figured out that these were not store bought trinkets, but the results of hours of wood carving, Keith's hobby. I mentioned pilot turmoil; Keith has not only witnessed that but he was in the thick of it. After 15 years the Air Force decided fully half of his year group had to go. So Keith went. By the time I caught up with him as a civilian, he had seen several flight departments go boom, then bust. He got me my first civilian job with Compaq computer. After two years it was bought out by Hewlett Packard. Most of us rats dove off the sinking ship as soon as we could, Keith stayed until the bitter end. And then he found another flying job. Calm through it all. Keith retired early, not so much to get away from aviation but to spend more time with his family and with his wood carving. I asked him how retirement was going and he had some sage advice.

I do think that a large number of folks approach retirement or a sudden increase in idle time unprepared. While carving does not generate any real income for me, I do really enjoy carving. It does not require a great deal of space/tools/money and (once you get decent at it) folks do enjoy receiving something that is handmade. I have a small shop (12 X 20) that provides enough space for me to work away from the main house.

Take your spouse into account as well. My wife told me "You can retire as long as you have someplace to go."

An important factor is to find something that gives you mental stimulation, is emotionally satisfying and does not require a great amount of physical strength or stamina. I have seen several guys that planned on playing golf or tennis or skiing only to find that their knees/back would no longer participate. You have your writing, Manno [more about him next] has his cartoons, I carve.

The only thing missing in my hobby is the ability to generate a sizable income from it. I don't market my carvings and only sell them via word of mouth. Most of the time they are just presents for folks I know or projects for a specific event that I am connected with.

I've known a lot of pilots over the years who had to find something else to do for a few years (like Ollie) or had to give up a dream to keep flying (like Harrison). I've known few more emotionally capable of leaving aviation than Keith, but he never really had to until he wanted to. He mentions Manno's cartoons. There is much more to Chris Manno than cartoons...

4

Plan B: develop an avocation that can become a vocation

I know three pilots who gave it up and became medical doctors. I know several that went on to become business CEOs and more than a few who went on to manage large academic institutions. There is no shortage of talent. What separates these pilots from many others is that once they became professional pilots, they didn't stop learning and expanding their horizons. Having a Plan B in case the flying thing ends, also opens up other opportunities and provides for the next chapter when it comes time to turn the page on aviation.

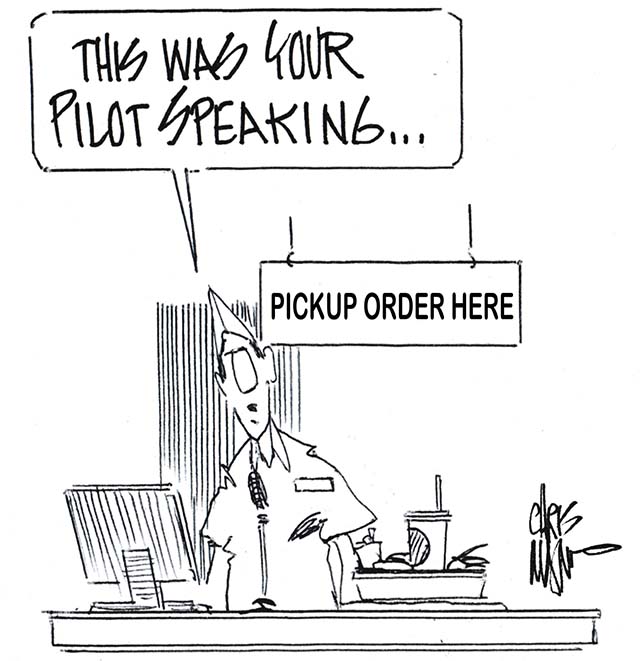

I first met Chris Manno in 1982 during my interview to fly the Boeing 707 for an Air Force squadron in Hawaii. He had an irreverent sense of humor about all things except aviation, which he took very seriously. He confessed to me a few years later that he wasn't cut out to be an Air Force officer and would rather be an airline pilot. And, by the way, how do you do that? Within a year of that conversation he was an American Airlines pilot. That was thirty-five years ago. He just retired this year. Through it all he was never furloughed but he always had a plan if that ever happened.

You might recognize his name if (a) you are a student at Texas Christian University, (b) are an avid reader, (c) frequent the local music scene in Dallas / Fort Worth, (d) view aviation blogs, or (e) read Code 7700.com. Allow me to explain.

Chris is one of those people that make me feel like I am standing still. He has more than his share of hobbies and he pursues them all with passion. He made captain with American while still in his thirties. That would have been the normal time to coast and take it easy, but that isn't what he did. He went back to school and got his PhD. He has always had a keen interest in literature and has been teaching lit at TCU for 17 years now.

I have several of Chris' novels on my bookshelf and I recommend them highly. You can see them all at Amazon. The first to win him awards was "East Jesus," but I recommend you start with "Sanctuary Moon."

For a time you could see Chris on stage with his band or on the local news as an aviation consultant. But his widest readership may be on line via his Jethead Blog, which has been bringing a view of the airline cockpit to the public for many years and has over 10,000 subscribers.

You may also recognize his name because he draws many of the cartoons here at Code 7700.com.

Chris just hit age 65 which is the terminal point for many airline pilots, the moment in time where an airline pilot's life is forced to end. Where many pilots at this stage are forced into the "what do I do now?" crisis anew, that hasn't happened to Chris. His teaching position at TCU has actually solidified and his most recent book was just rated a #1 new release at Amazon. The end of his professional aviation career wasn't so much the close of a book, but a turning of a page to next chapter.

5

A concluding thought

I think there is a broad spectrum of attitudes among professional pilots when it comes to thinking about no longer being a professional pilot. I used to think that was unique among Air Force pilots, since we spend so much time trying to get our wings and have to bear witness to the many who fell short. But now, so many years later, I realize this is a common thread for all professional pilots.

As a professional pilot you have survived what amounts to a rigorous selection process. You underwent significant hardship (monetary and/or time) and the fact so few even make the attempt, only solidifies the idea that what we are doing, we are doing in rare air. For many pilots, the thought of doing anything else is simply unthinkable. If offered a better life (once again, monetary and/or time) that didn't involve flying airplanes, we would say no.

On the other side of this continuum you have pilots who view the profession as one possible occupation of many, and that if it were to go away (or if something better were to come along), they would willingly jump.

As an Air Force pilot, I fell into both camps at various times. After getting my wings, using those wings was all I wanted to do. After about ten years, I wanted to do something, anything else. I did that twice, but I always came back. The strange thing is that I have gone through the same process as a civilian pilot. But I always came back.

Another strange thing I've noticed is that pilots from both camps are as likely to have one of two attitudes when it comes to doing something else. Some pilots plan for it, knowing that they are never more than six months away (or whatever the duration of their first class medical is) from losing it. They are always looking for a Plan B, hoping they won't need it. Other pilots refuse to think about it, saying "I'll cross that bridge when it comes."

All four pilots I've mentioned here have retired from aviation and I think all four are leading happy lives away from any cockpits. The process of getting from then to now was quite different, however.

As it turns out, the two pilots in the "I'll figure it out when it happens" did figure it out. But the process was rocky, involved mental anguish at times, and I am sure the uncertainty must have been psychologically draining.

The two pilots who developed another life outside of aviation didn't need to fall back on their avocations during their professional pilot tenures, but realized they would have a cushion to fall back on when needed. And they had something to look forward to after walking out of a cockpit for the last time.

So here I am, a year (or maybe two) from leaving my last cockpit. I do a lot of writing, some public speaking, and there is this Internet thing. I'm not getting rich off of any of it. But I do look forward to more of it. I recommend you find something outside of aviation that excites you as much as aviation. In the end, it will make you appreciate your life as a professional pilot even more.