The answer to many things in aviation, "because we've always done it this way," is another way of saying, "I don't know." More importantly, it disguises the follow up question, "is there a reason we shouldn't be doing it this way?"

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-06-15

I remember the first time I asked the question was as an Air Force student pilot flying the T-38. Takeoff and landing speeds in that thing was upwards of 150 knots and the list of crashes during takeoff and landing was long and impressive. But this was 1979, we had just ended a war where dead pilots were a part of the business, and we knew that "you have to expect a few losses in a big operation." And I did. In fact, when it came time to takeoff and land just a few feet from another T-38, I eagerly accepted the next challenge on the road to getting my pilot's wings. It was fun.

One day, waiting to takeoff as lead of a two-ship formation, I watched as two F-4 Phantoms approached in wingtip formation overhead at 1,000 feet. Each pitched out within a few seconds, splitting the formation. This spacing grew so that they could land about 15 seconds apart. This was a standard maneuver for us when we started formation flying but that was not what we had planned for that day. Our day would end with me just a few feet from the lead aircraft, relying on him to place his aircraft on one side of the runway while I landed on the other.

My instructor for the day was a FAIP, a First Assignment Instructor Pilot who had never flown in what we started to call "the real Air Force." My favorite IP in our training flight had been out there, in fact, he was a former F-4 pilot. I found him and told him about the F-4s I had seen that day. I asked him why they didn't land in formation. He thought it a stupid question. "Because that would be too risky," he said. In fact, he told me, nobody in the real Air Force allowed formation landings. "Then why are we doing it?" I asked.

"Because we've always done it this way."

That was in 1979. On November 21, 2019, a T-38 crashed during a formation landing at Vance Air Force Base, Oklahoma. The student pilot was flying the airplane while keeping an eye on the lead aircraft. Just after landing, while attempting to aerobrake (lift the nose to increase drag), the aircraft became airborne again, and struck the lead aircraft and then rolled inverted, killing both pilots. The lead aircraft was damaged, but both pilots survived. Of course blame for the accident was placed on the accident aircraft's instructor pilot and the Air Force considered the matter closed. The student pilot's parents issued the following statement:

“The report’s conclusions omit a significant, if not the primary cause which is side-by-side formation landing in a 58-year-old jet despite the report’s backup documentation shining a bright light on this dangerous and wholly unnecessary maneuver,” they wrote. “By omitting this obvious contributing cause, the Air Force is not compelled with sufficient urgency and transparency to reassess the cost-benefit of student fighter pilots, and for that matter instructor pilots, engaging in an inherently dangerous practice with no continuing practical benefit to combat pilot proficiency or survivability.”

So thirty years after I was taught formation landings, the Air Force is still teaching pilots this "wholly unnecessary maneuver." I am certain someone in the Pentagon will tell you the maneuver is needed to evaluate the student's ability to fly precisely, etc. But I doubt they could justify the cost versus the benefit. I think the real answer is, "because we've always done it this way."

Are we, as civilian pilots, doing things because we've always done it this way? Things that, if we had a moment to reflect, are not worth the risk? I can think of a few:

1 — Non-towered operations in IMC or VMC

2 — Two first officers with a captain on extended range operations

3 — Passengers in the jump seat for takeoff and landing

5 — Air Driven Generator "test flights" by untrained crews

Am I saying we should stop all of these practices? Not really. What I am saying is we should not accept doing these things "because we always have" and look for safer alternatives where those alternatives are available. In my flight department, we no longer allow circling below VFR minimums, for example. For these examples and others, there are ways to mitigate the risk and often the best mitigation is avoidance.

1

Non-towered operations in IMC or VMC

I must admit up front that I am an IFR pilot. I got my instrument rating concurrently with my very first pilot's license, a commercial instrument, multi-engine. The Air Force's rule about these things was printed in our regulations: "Fly IFR to the maximum extent possible." To say I don't much care for using airports without operating control towers would be an understatement.

In my current operation we do use a few airports without control towers and most of the pilots of VFR traffic have been quite good. Most use proper entry procedures, take care to announce themselves and intentions on common frequency, and have been very good about getting out of the way when faster jet traffic arrives off an instrument approach.

We operate out of Hanscom Field, Bedford, Massachusetts where the tower closes shop between 2300 and 0700 every night. But airport operations is in 24 hours a day, monitoring the condition of the runway, and ensuring at least one runway is ready at all times. The airport is completely fenced in and even the most itinerant turkey is escorted from the premises. Not everyone has it so good.

Much to worry about . . .

Two years before I started flying, a cow wandered onto a runway at Castle Air Force Base, where a KC-135A was doing touch and go landings. The latter struck the former and everyone lost. Airplanes are not designed as well as cars when it comes to surviving an altercation with wildlife. There are several advantages to having an operating control tower, the primary of which is there is someone keeping an eye on things.

Cessna 550 N6763L encounter with deer, ERA13LA061

Click photo for the case study

Of course if you are operating on an IFR flight plan, someone is watching you until you cancel that flight plan. But even if you get released for your instrument approach, there is one fewer crosscheck available to ensure the runway is okay to use.

Beechjet 400A XA-MEX after its snow plow encounter, CEN16LA067

Click photo for the case study

If you feel perfectly safe at a non-towered airport, I encourage you to look at these two case studies. Also consider that some airlines make decisions on where to provide service based on the availability of an operating control tower. (Example from 2019, Allegiant Airlines pulled service from Fort Collins and Loveland, Colorado because of this.)

2

Two first officers with a captain on extended range operations

Before I became a pilot, I just assumed those two people in the front of the airplane new what they were doing. Even after getting my wings, I more or less gave the two pilots up front the benefit of any doubts. Then a few weeks before Christmas in 1985, I was supposed to fly on a small commuter from San Francisco to Sacramento. The flight was delayed because of fog and I elected to trade my ticket in for cash and rented a car instead. The flight was eventually canceled. Two days later, an airplane from the same airline undershot the Sacramento airport and crashed into a shopping mall. The pilots simply drifted below their minimum descent altitude.

We flew from Hawaii to Sacramento for a lot of training back then and it became my practice to drive from San Francisco. In fact, I have done that a lot over the years. Many business jet pilots based in the Boston area do their training in New Jersey and get there on regional airlines. Not me, I drive. I always had faith in the major airlines. They had better pilots and better equipment. But that faith has since been shaken too.

Several years before the crash of Air France 447, I flew with a former first officer of a very big major U.S. airline. He called himself an international airline pilot, because he flew international routes for an airline. He was a pretty good pilot but fairly ignorant about international procedures. As I got to know him, I found that he also lacked knowledge about high altitude flight. I then found out that he was an "Extended Relief Pilot," his purpose at the airline was to sit in a pilot seat when one of the other pilots needed a break. I didn't give this much thought, thinking that there would be a captain up there and I didn't have to worry about a poorly qualified first officer up front. But I was wrong.

I was quite surprised by many facets of the Air France 447 crash. The fact the pilot flying the airplane pulled the nose up as high as he did at a high altitude, that was surprising. The fact the Airbus would allow one pilot to pull back on the stick while the other pushed forward, all the while each pilot didn't know that the other was doing the opposite, that was surprising. But what surprised me most was that the airplane was being flown by two first officers, neither of which had more than six years experience with the airline or flying anything larger than a small trainer. The captain was in back. Of course it should not have surprised me, the airline isn't about to put a second captain as a relief pilot, that would cost more money. I suppose if you train the first officers well enough it isn't a problem. But what airline is going to spend more than the absolute minimum to season a young first officer? I think the entire Extended Relief Pilot as most have implemented it, is flawed.

3

Passengers in the jump seat for takeoff and landing

Early in my career flying the Boeing 707 (EC-135J) one of our sister squadrons lost an airplane (EC-135N) with everyone on board while the pilot's wife was in the left seat and another wife was standing or was seated in the jump seat. The pilot in the right seat was distracted as the pitch trim ran away and was unable to recover from the violent dive that resulted. More about that: Case Study: EC-135N 61-0328.

I've never permitted a non-cockpit crewmember into a pilot's seat while flying, though I have had my wife and daughter in the jump seats of a few of my aircraft. I've since had a change of heart about this practice.

A careless and reckless G550 pilot, encouraged by an equally careless jump seat passenger

Click photo for an article about this particular flight

We pilots are human and, as such, can be distracted. Having a non-crewmember in the jump seat is a distraction.

For those of us flying most business jets there is an additional problem to consider. Emergency egress with the jump seat occupied can be an issue. We have gotten around any requests for the jump seat with a written policy that only people with formal egress training are allowed in the jump seat. That formal training cannot be accomplished by any of us in the flight department and the only people we fly with who have the training are our two authorized flight attendants and our two mechanics.

4

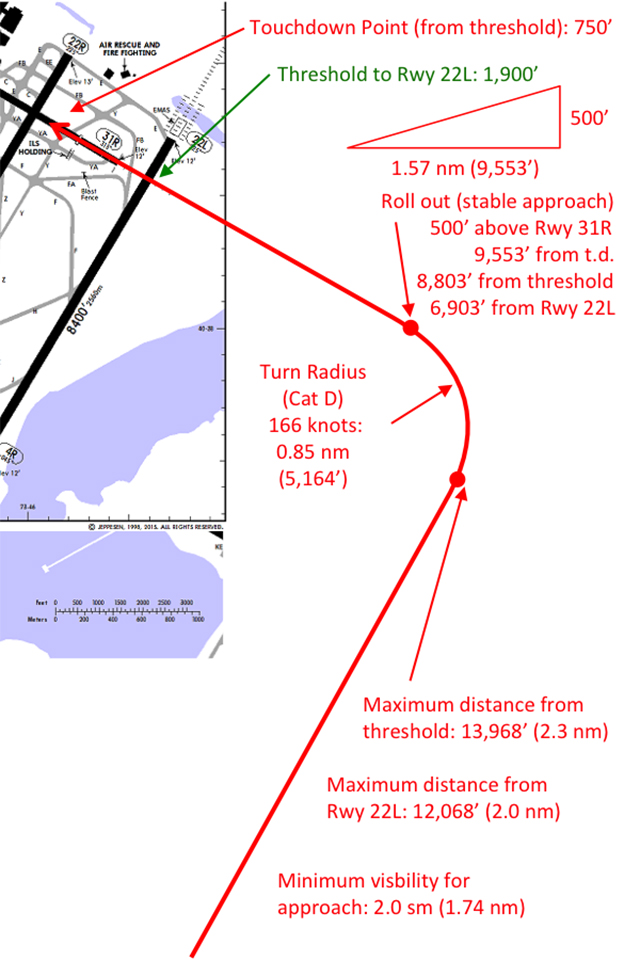

Circle to land procedures

When I was a first lieutenant Boeing 707 copilot in Hawaii I attended an instrument refresher with a collection of mostly fighter pilots, a fair number of helicopter pilots, and one other of us "heavy" pilots. The instructor put up a slide of a circling approach and asked the A-10 pilot in the front row what he would do if cleared this particular approach. "I would declare an emergency because that kind of approach is a bad idea for a guy flying a jet, single-pilot." I thought, at the time, he was a buffoon. Now, nearly forty years later, I think he had it right all along.

I have circled at minimums more than a few times over the years, but not recently. Most of my recent experience circling at minimums is done in the simulator. If the instructor is being a bit of a jerk otherwise, I'll ask him if he wants a stable approach or a circling approach. Of course he'll say both. And then I will demonstrate just how impossible that is. More about this: Approach Impossible.

We've written into our rulebook that a circling approach can only be done at VFR weather minimums. At night, we only allow it at our home airport and two others that we know very well. And we insist on a stable approach, hence the need for VFR. Ten years ago and earlier, you could argue that if you didn't circle much of the world was cut off from you. These days with GPS, that is less and less a valid excuse.

5

Air Driven Generator "test flights" by untrained crews

Some of the things we are called upon to do start out as well thought out and reasonable. But as time passes pilots take short cuts and before you know it, you've converted something safe into something risky. This is especially true of functional check flights.

With less than a year of experience in the Challenger 604, I was handed the task of doing a test of our aircraft's Air Driven Generator (ADG). Everyone else found an excuse to be someplace else and the pilot I was paired with agreed, provided I be the Pilot in Command as well as the Pilot Flying. He appeared to be afraid of the entire process, though he had witnessed it a few times.

I pulled out the manufacturer's procedure and flew the test. It was all rather mundane and not particularly exciting. I found out that the flight department's policy had been to do the test in the traffic pattern, in a matter of ten minutes. I flew the airplane to 10,000 feet and took my time, the sortie was an hour.

I've since been told that it is common practice to do the test on short final, day or night, IMC or VMC. The test puts stress on the aircraft's electrical and hydraulic systems and finding out about any problems on short final is not what I would consider sound practice. And yet, fifteen years later, I still hear of Challenger crews getting themselves into trouble with the test on short final. Why are they doing it that way?

"Because we've always done it that way."

I have a two word answer to that and everything else we've discussed on this page: Stop it.

References

(Source material)

Accident Final Report, and Accident Docket, CEN16LA067, National Transportation Safety Board, Adopted 04/17/2018

Accident Final Report, and Accident Docket, CEN16LA067, National Transportation Safety Board, Adopted 04/17/2018