In this “Being Better” series, we’ve looked at being better students, pilots, crewmembers, and captains. Taken as a whole, you might say we have looked at a broad range of being better as professional aviators, but I think it goes much further than that. If you are truly a professional aviator, the line between your professional and personal lives becomes blurred. And that, contrary to popular wisdom, is a good thing. If you want to become a better professional, you must become a better person first. And that will require some introspection.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-07-20

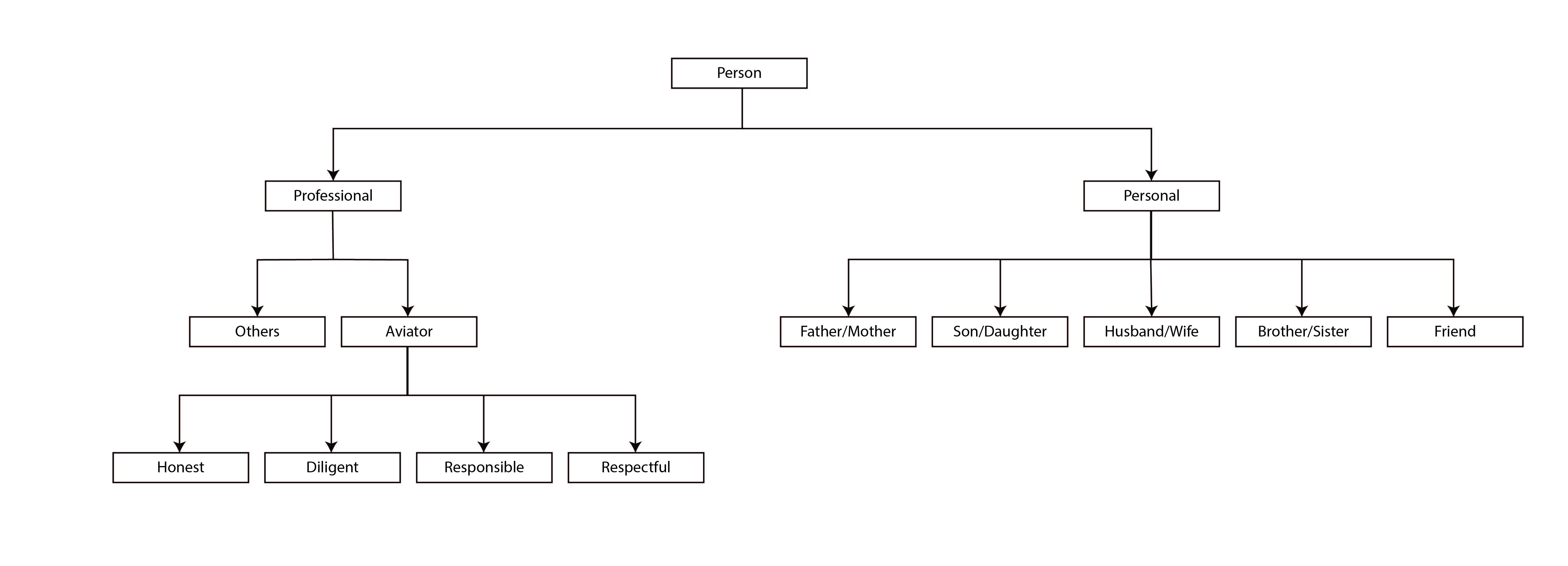

In a previous “Being Better” article, we examined where a specific instrument pilot skill fell in a chart of pilot skills. If we expand skills to encompass all there is about the idea of being better, we can examine “identities” to great advantage. We can go higher in the spectrum and examine where pilot identities fall under your realm as a productive human being. Everyone’s identity map will be based on personal experiences, but we can look at a generic map as an example.

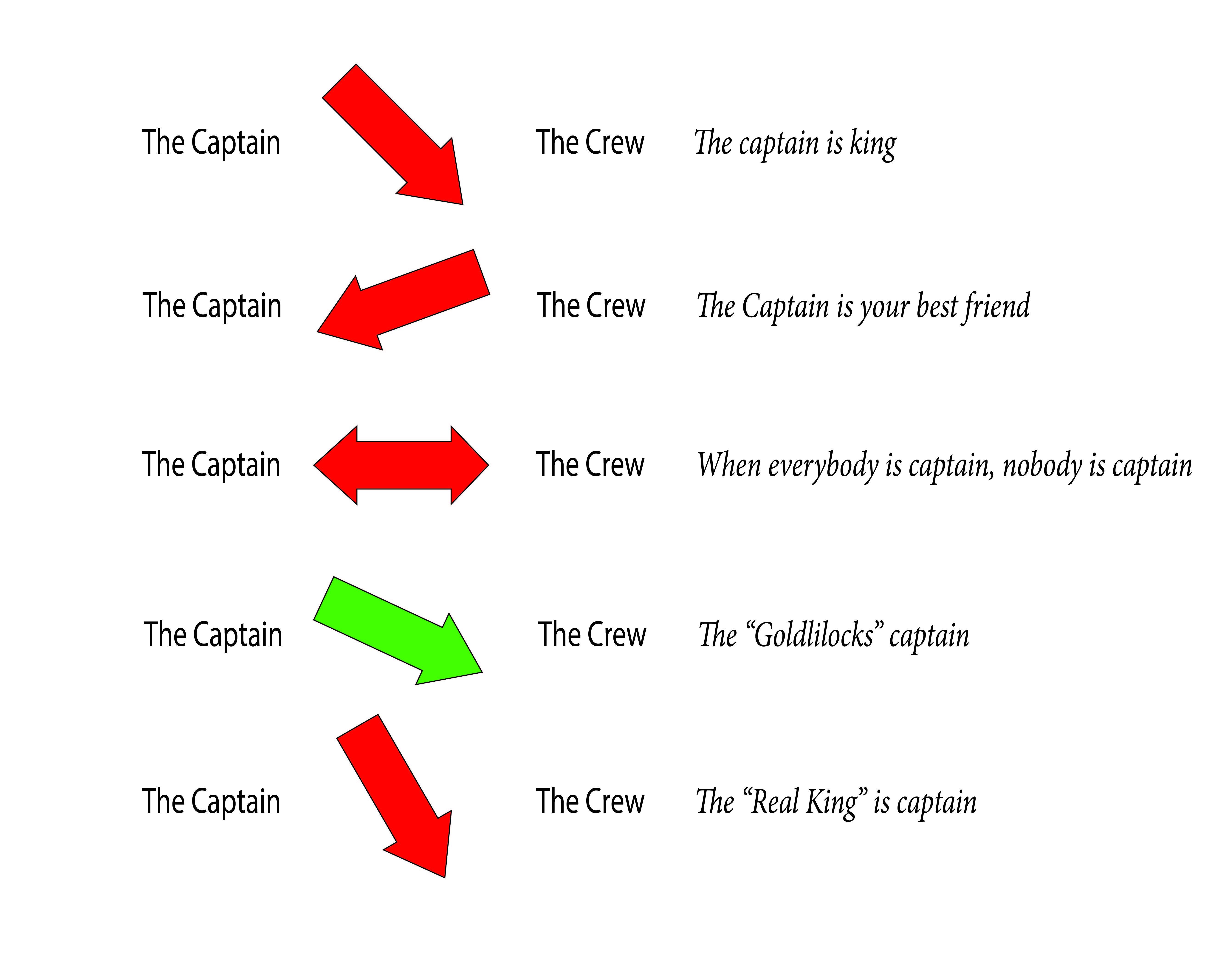

Who are you? Do you first think of yourself in terms of your professional or personal lives? There is no right answer. Many of us aviators have other professional lives, and our personal lives can be more simple or complicated than the example shown. Looking only to the aviator aspect of our professional lives I think it should be a given that we expect a certain level of skill and knowledge is required. I believe this is a prerequisite to being able to call yourself a professional aviator.

When I think about what character traits are needed for any aviator to become a better aviator, I think of honesty, diligence, responsibility, and respect. Without these four traits, any hope of becoming a better aviator is diminished. I would extend these traits to all of the identities.

1

Diligent

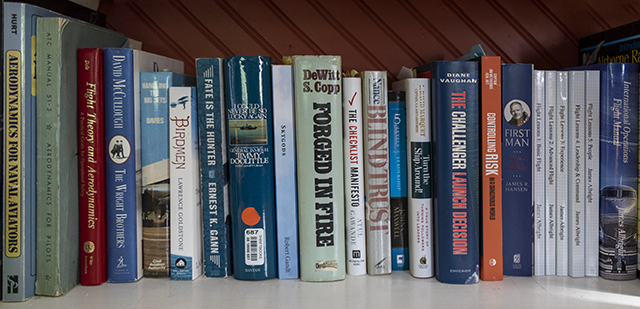

We instinctively know that getting better at any skill takes practice. But once we’ve attained a lofty goal, such as an Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) rating, it may be less obvious that our work has just begun. As my next example says, the ATP is a license to learn.

A friend of mine based out of China flies literally around the world on a regular basis and sees many of the world’s capitals the way I see Teterboro and Washington Dulles: they are second homes. But it didn’t start out that way. He grew up in Venezuela, started flying in Colorado where he graduated to professional flying via the Certified Flight Instructor (CFI) route, and returned to Venezuela as a corporate business pilot. Fast forward many years and you will see his logbook includes the Beechcraft King Air, the Douglas DC-3, multiple Learjets and Challengers, the Bombardier Global Express, and now a series of Gulfstreams. There were setbacks along the way, but he treated each as a learning lesson and always treated each new break and challenge as opportunities to learn. He makes me feel like I am standing still, and that is about the highest compliment I can give another pilot.

Unfortunately for every diligent, nose-to-the-grindstone pilot, there seems to be another side of the coin lurking out there. I was once paired with a young pilot on his initial operating experience trip with the company and thought we had a promising prospect. He knew the aircraft’s operating limitations and procedures though his flying was a little sloppy. After our first day of flying, I thought he just needed some proficiency, and I could sign him off as good to go. When we checked in to our hotel that night he was asked for his hotel rewards number, and he spouted that off without looking for the card. I asked him if he had all his numbers memorized and he said that he did. I’ve heard of people with photographic memories, but he was the first I ever met. In the week to come I realized that he did indeed have the airplane memorized, but he struggled when it came to flying the airplane. I signed him off with a note he needed some seasoning. That was an appropriate comment because it turned out he was also a world-class chef and had several other talents that would benefit from his encyclopedic mind. Everything came easy to him, but he was unwilling to apply much effort to taking it to the next level. His skills never improved and we had no choice but to let him go. He bounced from job to job in a steadily downward vector. To this day, all of us who flew with him say the same thing: it was a waste of talent.

2

Honest

You cannot be a better pilot unless

you are honest with yourself

Click photo to view "Being a Better Pilot"

You cannot hope to become better at anything unless you are honest with yourself first. You must recognize your own shortcomings to conquer them. Furthermore, you must be honest with others so that they will trust you enough to help along the way. I have many examples, both good and bad, but two stand out for me.

Several years ago, I shared the stage at the Bombardier Safety Standdown with a young airline first officer who got hired very early with a new airline and blazed a trail of one success after another. She aced every training program and got high marks for poise under pressure following an engine failure with an airplane full of passengers. She is young, but she looks even younger. I thought for sure she would turn a few heads when her line number came up for captain. I was fortunate enough to meet her shortly after that day came but was surprised that she had turned the left seat down, at least temporarily. She told me that while she felt ready for the flying tasks of the captain’s seat, she wanted some time to understand the crew leadership challenges. Her honesty with herself will translate to self-improvement well beyond her aviation career.

On the opposite side of honesty, I once hired a pilot who had the right ratings but not enough experience for anyone to take a chance on him. I took that chance, giving him exposure to facets of aviation he was unfamiliar with, such as international operations and the busy Northeast corridor. I noticed an unwillingness on his part to be self-critical and that limited his ability to self-correct any deficiencies. But I didn’t give up on him until he gave up on us. With minimal notice he quit, and we found out after the fact his plan all along was to gather the experience needed to find a job in another location. I believe he is rather proud of himself for the way he played us, which fits with what we saw in the cockpit. In his mind, everything he does is right, and he will never improve because of this dishonesty.

3

Respectful

A final trait of a person capable of being better is that of respect. You cannot motivate yourself to be a better professional if you don’t respect the profession, your peers, and yourself. It is a sine qua non, without this, nothing.

Another friend of mine who grew up starting out as a CFI got his start as a jet pilot interning for a simulator training company. In this position his job was flying early model Gulfstreams as the expert in the right seat, helping clients to learn and pass check rides. The company recognized his talents as an instructor and promoted him to a management position in the training program. He rapidly became known not only for his skills as a pilot, but as an instructor. He was rapidly scarfed up to fly a variety of aircraft under Part 91 and Part 135 operations. Through it all, he has maintained instructor status and has become a “go to” source for many in the Gulfstream G150 and G450 worlds. I know he has a great deal of respect for his profession because he takes all aspects of it seriously. Whether we are talking international flight operations or flying a glider in mountainous areas, he is a student, a practitioner, and an instructor. He is always the first to compliment and the last to disparage. Those are fine traits for any professional.

While I have had the great fortune of knowing many fine, respectful people, I’ve also known a few on the opposite end of the spectrum. I spent a few years working for a pilot whose primary techniques for instructing were sarcasm and ridicule. I often felt like a marriage counselor, trying to convince flight attendants that he wasn’t angry at them or first officers that he didn’t mean to openly insult them in public. He ended many of his critiques with, “I’m surprised you didn’t know that” or “anyone worth their paycheck knows that already.” When it came to light that he was wrong and the target of his derision was right, the subject was quickly changed. He vigorously enforced Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) he favored and with equal energy disparaged those he didn’t like. I concluded that he did not so much respect the pilot profession as he did the ability to call himself a professional pilot. In the end he bounced from employer to employer, alienating a new crop of peers, until he was asked to retire for good.

4

Responsible

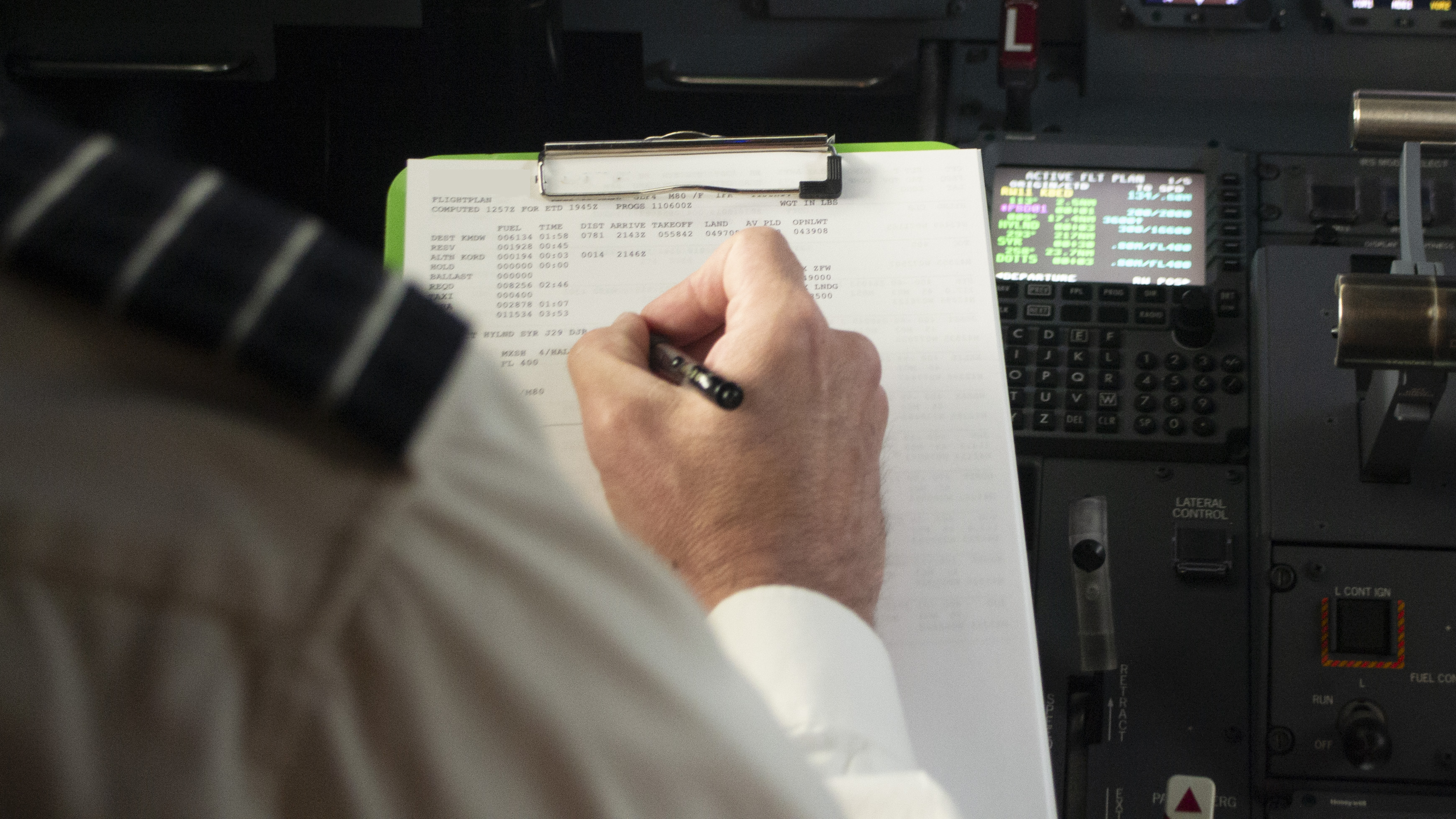

The idea of “being better” requires a motivating force and for most of us it is an act of responsibility to ourselves, our families, and our employers. It is said that a prime motivator for those of us who started in the military was that we didn’t want to let our buddies down in combat. I think life outside the military can also be a battle at times and it is our responsibility to be there for our “buddies.”

Another friend of mine just retired from thirty years as a helicopter pilot flying for a large sheriff’s department. Like all members of law enforcement, his responsibility was to the public. Unlike those on the ground, however, his job was complicated by the fact he was flying a rotary wing aircraft day and night, in good weather and bad, at low altitudes in congested areas, and sometimes while being shot at. His responsibility for operating safely was certainly complicated by the very nature of the job. He was challenged to balance the demands of the people in the organizations against his sworn oath to “to protect and to preserve.” It was a political organization and not everyone he flew with had what it takes to fly safely. There were times he had to face down higher-ranking officers who didn’t understand the risks involved when operating aircraft, but to do so in such a way to preserve the organization itself. I think many of us professional aviators face a similar challenge. We have a responsibility to those who employ us to fly our aircraft as they see fit. We do our jobs so that they can do theirs. But like my friend from the sheriff’s department, we must balance their demands against our judgement to be able to do that safely.

As an Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (AFROTC) cadet I naturally looked up to the upperclassmen cadets who seemed to be immersed in aviation and their future careers as pilots. One of the most driven even had a complete set of flight manuals for an airplane I would eventually fly, the KC-135A tanker. He was fun, charismatic, and a natural leader. He started his Air Force pilot career as a primary instructor, training other pilots. I thought at the time he was biding his time until he would eventually discover his destiny as an operational pilot. But, as it turns out, he was too busy having a good time and, in his words, did not want to grow up. Even as a cadet I knew he was a heavy drinker, but it wasn’t until we spent a few months together in an Air Force leadership school did I discover just how much alcohol consumed his life. He paid less and less attention to his duties as a professional pilot and after an arrest for driving while intoxicated, he was deemed too irresponsible to be an Air Force officer and was discharged. The pattern repeated itself during his civilian career and he eventually died from the disease. As with the previous negative example, all who knew him thought it was a waste of talent.

5

Balancing professional and personal identities

If you examine the four traits here – diligence, honesty, respectfulness, and responsibility – it should become clear that each applies to every facet of your identity. If you lack any of the traits as a professional, you probably fall short of the same quality in your personal life. But that brings up the question of balance. How do you balance the demands of your professional life against your personal life? Does your effort to become a better aviator necessarily subtract from your personal life?

Only you can answer the question for yourself but since your chosen profession deals with life and death, your answer will have to consider the consequences of being wrong. Throughout the years my decision has been to study and devote whatever time it takes to satisfy all the legal requirements first, and then to satisfy myself that I am able to handle whatever is likely to come my way. The time left over goes to my family and what is left over after that can go to any personal hobbies.

It is easy to say I will prioritize my family first, but consider the consequences of falling short as an aviator if it cost you your job or your life? I think if the demands of aviation leave you without enough time for family, then the answer is to quit aviation altogether. It is a profession you cannot apply half effort to. But it is more than that. It is a profession you must continually strive to get better at just to keep up.

6

Better than whom?

A natural question in this quest to being better is “better than whom?” (Or “better than who?” depending on your grammar preferences.) My answer came to me in one of my Air Force squadrons. My introduction to the Boeing 747 was with a group of highly competitive pilots who vied to become the best the squadron had. We measured “best” in any category you could imagine, including the best landings, the best instrument approaches in the crummiest weather, the best air refueling, even the best taxi technique. I found it fun but also tiring. Then one day one of our pilots seemed to switch on and suddenly mastered everything. It became obvious he had a gift that none of us could comprehend. I overheard one of the pilots say, “I give up! What is the point when we can never do what he does?”

Having raised two children, I’ve heard the question repeated many times in different contexts. “Why can’t I run as fast as Ryan?” “Why is Sally number one at everything?” Both kids are grown adults now and are comfortable with their places in life. I don’t know if my answer to them had an impact on them, but it has helped me. I told them, “You don’t have to be better than anyone else. You just have to be better than you used to be.”

7

Being better

When I started out this five-part series of being better, I knew right off the bat there is an element of hubris in me that deserves critique. “What gives you the right to tell us how to be better at anything?” That is valid and the answer is this: “Nothing at all.” I’ve spent a lifetime trying to be a better aviator, husband, father, and friend. I sometimes fall short in all categories. But I keep trying. And that is my message in the end: keep trying.