Book Review Birdmen: The Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss, and the Battle to Control the Skies; Lawrence Goldstone

As the name implies, Lawrence Goldstone’s “Birdmen” deals with more than just the normal focus of these books about the Wright Brothers. He goes into a fair amount of detail on the other players who had a role in the first decade of powered flight. I learned a lot that I didn’t know about these other characters in this play, but I learned a great deal more about Wilbur and Orville Wright.

It isn’t that I am a novice in the subject. I have six books about the Wright Brothers in my library, probably the most well-read version is by David McCullough under the unimaginative title, “The Wright Brothers.” One of my favorites is by Orville Wright himself, called, “How we Invented the Airplane.” Birdmen is unique, I think, because it gives you a look into so many of the other important personalities.

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-02-01

Those who paved the way

German engineer Otto Lilienthal had a profound effect on early wing design:

“He was, rather, the most sophisticated aerodynamicist of his day. For thirty years, he had taken tens of thousands of measurements of variously shaped surfaces moving at different angles through the air using a “whirling arm,” a long pole that extended horizontally from a fixed vertical pole and spun at a preset velocity, a device originally developed to test the flight of cannonballs. In 1889, Lilienthal had produced the most advanced study ever written on the mechanics of flight, Der Vogelflug als Grundlage der Fliegekunst – “Bird-flight as the Basis of Aviation.”

Octave Chanute, born in France but brought to the U.S. at an early age, made his fortune as an engineer designing railroads, stockyards, and bridges. In retirement, he decided to learn all he could about aircraft design and became an early correspondent to many who would do the actual designing, including the Wrights.

There were many others. Perhaps I should mention French expatriate Louis Pierre Mouillard, who as early as 1896 experimented with ailerons as a means of control “which permits going to left and right.”

Those who got in the way

There were many charlatans and opportunists, two of whom merit comment. Leading the former category was Augustus Moore Herring, son of a wealthy cotton broker who designed gliders that never flew and claimed to have designed mechanisms he never built and tried to convince others he had patents and extorted payment as a result. Glenn Curtiss was such a victim, signing into a partnership believing Herring had patented the aileron. While Herring had an unscrupulous reputation and almost never won a lawsuit, his heirs manage to win one in his name after the Wrights and Glenn Curtiss had died, winning a $500,000 judgement against Curtiss.

I place Samuel Pierpont Langley in the opportunist category because of his political skill in getting appointed as the assistant secretary of the Smithsonian Institution knowing the secretary was near death. Langley took over and used his position to win lucrative government contracts in the race to powered flight. He eschewed theory and details. In fact, he named his first airplane the “Aerodrome,” not realizing or caring that he used the name for a place, not a vehicle. From the book:

“Obsessed with creating a machine that would remain perfectly stable in the air, Langley had employed the dihedral wing arrangement to prevent his aerodrome from dipping to one side. [. . .] Instead of avoiding roll, Wilbur embraced it.”

Those who got it done

Langley, like many others of the day, believed the best model for future airplanes was the present-day automobile. All you needed was enough power and something so stable that it couldn’t be upset during flight. The Wrights, owners of a bicycle shop, and Glenn Curtiss, motorcycle pioneer, understood the problem was maneuverability. Aircraft that are too stable are impossible to control and if upset, impossible to recover. An aircraft that is unstable is maneuverable. It increases pilot workload, but it provides the pilot with an airplane that can be controlled.

We often hear that the magical breakthrough for the Wrights was wing warping as a means of achieving maneuverability. In fact, the patent specifies wing warping for roll control and a rudder for yaw control. As Wilbur said, "It is our view that morally the world owes its almost universal use of our system of lateral control entirely to us. It is also our opinion that legally it owes it to us."

I find it odd that the Wrights angled their patent to this idea, since the idea itself had been out there before them. They were lucky the patent was awarded and luckier still that other means of lateral control, specifically ailerons, were credited to them where no credit was due. I think where they really broke new ground was in airfoil design.

Otto Lilienthal had voluminous tables of air foil data that the rest of the world assumed was correct. After their first forays into Gliders, the Wrights realized much of Lilienthal’s data was wrong.

“My brother Orville and I built a rectangle-shaped open-ended wind tunnel out of a wooden box. It was 16 inches wide by 16 inches long. Inside of it we laced an aerodynamic measuring device made from an old hacksaw blade and bicycle-spoke wire. We directed the air current from an old fan in the back shop room into the opening of the wooden box. In fact, we sometimes referred to one of the two open ends of the wind tunnel as the ‘goesinta’ and the other end as the ‘goesouta.’ An old one-cycle gasoline engine (that also turned other tools in the shop such as our lathe) supplied the power to turn the fan. This was because there was no electricity in our shop. In fact, even the lights were gas lights.”

I think aiming the patent towards methods of aircraft control were doomed to fail. The real genius was in airfoil design.

While Wilbur Wright was a brilliant intuitive scientist, Glen Curtiss was a superb craftsman and designer. After the Wrights’ first powered flight, Curtiss was already selling superior lightweight engines and offered to build one for the Wright Flyer. After Curtiss began flying airplanes of his own design, the Wrights suspected he had stolen ideas from seeing the Wright Flyer. By 1909 it seemed the Wright patent wasn’t deterring anyone and Curtiss was not alone flying other aircraft designs. All that changed the next year:

“On January 3, 1910 [. . .] federal district court judge John R. Hazel granted the Wright Company’s request for an injunction enjoining the Herring-Curtiss corporation and Glen Curtiss and Augusts Herring personally from manufacturing, selling, or flying airplane for profit. Hazel, with no training in aerodynamics, nonetheless went into great detail in an opinion that accepted every assert of the Wrights and none of Curtiss.” The injunction had little impact in Europe but had a chilling effect over aircraft design and manufacturing in the United States.

Why was Wilbur so consumed with litigation?

The obvious answer about Wilbur’s single-minded focus on enforcing the patent was to profit from the monopoly he felt their invention had entitled them to. At one point, they demanded $1,000 per aircraft and a quarter of all proceeds from the lucrative airshow markets that sprung up in the 1910s. But there was more to it than that.

Wilbur’s father was a pastor and later a bishop in the Church of the United Brethren in Christ, which had its beginning in Pennsylvania, Virginia, Maryland, and Ohio. When the church began to divide between strict adherence to the church constitution and those wanting social change, Wilbur’s father led a breakaway sect holding to strict adherence. Wilbur spent much of his early adulthood defending his father. “Both were extremely litigious and acutely sensitive to perceived injustice.” He would carry this forward years later in his defense of their patent. To Wilbur, the fact they had a patent entitled them to all the spoils of the invention and that anyone partaking in any kind of powered flight owed them for the privilege.

Glenn Curtiss was not the only target to the Wright litigation, but he somehow became the brothers’ primary focus. The Wright’s suspected him of stealing ideas, ignoring the fact many of Curtiss’s designs were nowhere to be found in Wright aircraft. While the Wrights seemed to stop innovating with the original Wright Flyer, Curtiss continued to improve his many designs until the legal battle slowed him considerably.

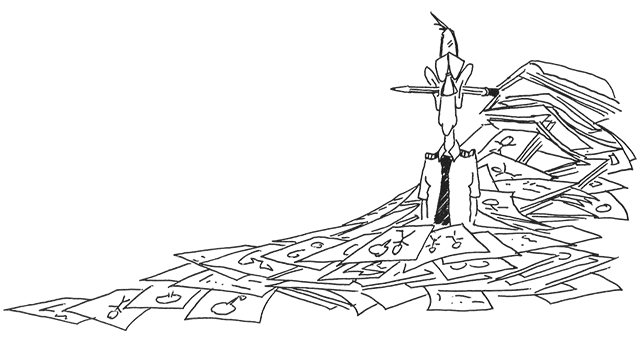

What was the true cost to aviation of the legal battle?

There is no doubt the litigation and fear of Wright lawsuits had a chilling impact on aviation in the United States until 1917.

“Although the litigation continued, it was largely of its own momentum and bore little resemblance to the ferocious legal wrangling of previous years. Even the formality of a lawsuit vanished with America’s entry into the war in 1917. To ensure that the very best American airplanes were available for the war effort, a board was created to draft a cross-licensing arrangement that would allow any manufacturer to use any patented process for a modest fixed fee. But the battle between the Wrights and Curtiss had taken its toll. Not a single American airplane design was deemed worthy to be adapted to combat flying.”

What of the Wrights?

Wilbur had become emaciated and physically spent with the legal effort and died of typhoid fever at the age of 45. Some family members say it was the legal battle that killed him. Orville took over the business which he eventually sold. He and his brother were lifelong bachelors; Orville the more reclusive of the two.

“For all his achievements and notoriety, it is difficult to view Orville Wright as anything but a sad and lonely man who never found his calling – and perhaps never even sought it – and who died without ever making a single friend."

And the book?

I found the book entertaining and educational. I have an increased respect for Wilbur Wright’s scientific genius and an increased disdain for the American legal system.