Here is an example of how the cause of a mishap can be obscured by press coverage, a good pilot's union, and a public's need for a hero now and then.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-06-07

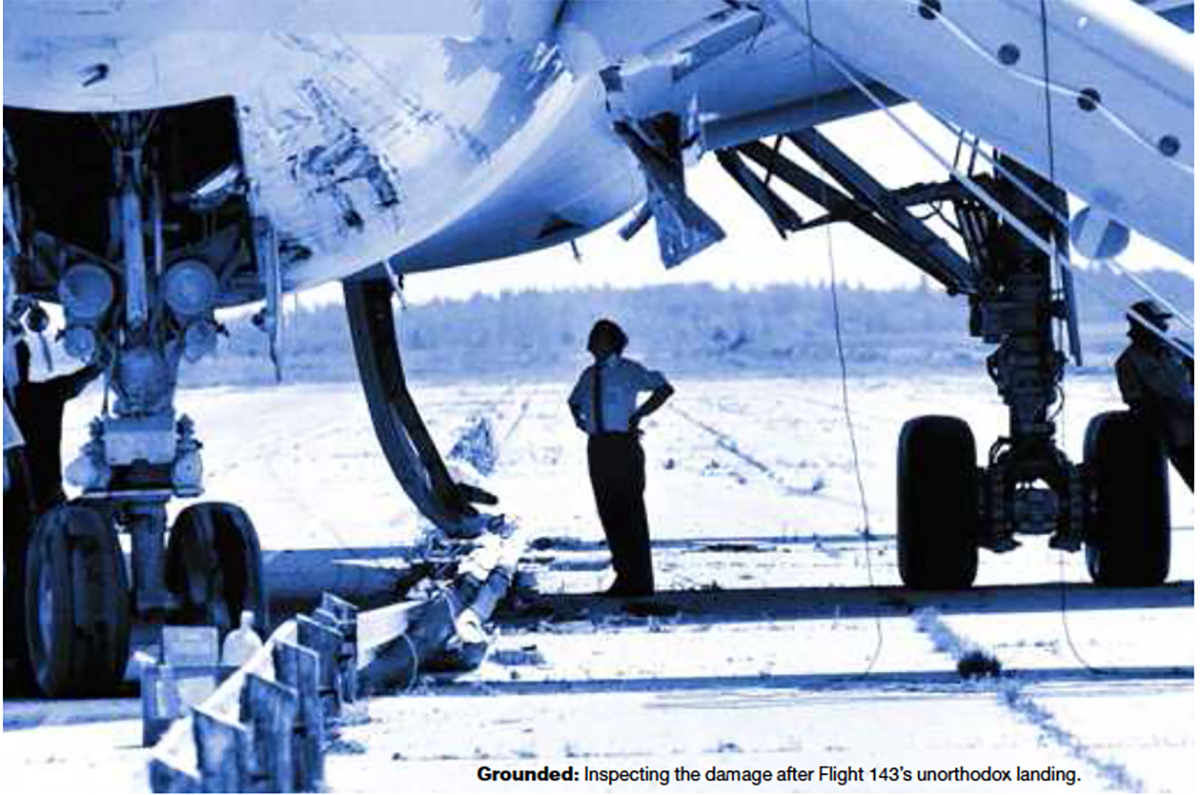

The captain of this airplane did a magnificent job dead sticking a Boeing 767 to a landing on an abandoned air field. The first officer did a great job of computing glide ratios and keeping the captain informed. In fact, the performance of this crew in Crew Resource Management and Situational Awareness was superb from the moment they suspected they were out of fuel, all the way through the successful emergency landing, passenger evacuation, and aircraft fire fighting. Excellent.

The problem is that both pilots were instrumental to the fact the airplane took off without enough fuel.

1

Accident report

- Date: 23 July 1983

- Time: 08:40

- Type: Boeing 767-233

- Operator: Air Canada

- Registration: C-GAUN

- Fatalities: 0 of 8 crew, 0 of 61 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Repaired

- Phase: En route

- Airport: (Departure) Ottawa International Airport, ON (YOW, CYOW), Canada

- Airport: (Destination) Edmonton International Airport, AB (YEG/CYEG) Canada

2

Narrative

During a routine service check, the three fuel quantity indicators, or fuel gauges, situated on an overhead panel between the two pilots, were found to be blank. One gauge is for the centre auxiliary tank, one for the left main tank and one for the right main tank. . . . These gauges are operated by a digital fuel gauge processor which has two channels. Either one of the channels is normally sufficient to ensure satisfactory operation of the processor to provide fuel indication of the gauges in the cockpit.

[A technician] found that he could obtain fuel indication by pulling and deactivating the channel 2 circuit breaker. . . . With this kind of problem an aircraft can only be dispatched after compliance with the conditions of the Minimum Equipment List (MEL). . . . [The technician] then dispatched the aircraft after complying with the qualifying conditions of MEL item 28-41-2. Under this item of the MEL, because one of the processor channels was inoperative, the fuel load had to be confirmed by use of the fuel measuring sticks located under the wings of the aircraft.

Source: Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident, Part II

The aircraft was then flown from Edmonton to Montreal via Ottawa. All three fuel gauges operated normally. The pilot of that trip briefed the new pilot about the MEL item, but the new pilot was under the impression the gauges were not working and the aircraft was flown that way. Meanwhile a technician in Montreal reset the circuit breaker to further trouble shoot and determined a new processor was needed. He tried to order one but was told none were available. He forgot to repull the circuit breaker. When the new captain showed up, the breaker was not pulled and his three fuel gauges, therefore, were blank.

{The new captain] knew that the aircraft was not legal to go with blank fuel gauges. He testified that he had raised the question of legality with one of the attending technicians who assured him the aircraft was legal to go and that a higher authority, Maintenance Central, now renamed Maintenance Control, had authorized the operation of the aircraft in that condition. No such authorization had been given. There is even some question as to whether this conversation took place.

Source: Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident, Part II

Even if the conversation had taken place, pilots must understand their responsibility for the safety of the flight outweighs any "higher authority."

[It] should be noted that for some years now all aircraft in Canada have been fueled in litres. That is to say that fuellers deliver fuel and charge for the fuel by the litre. On the other hand, those who calculate the load of the aircraft and those who fly the aircraft do not work in litres, which is a measure of volume, but rather a weight measurement.

Prior to the introduction of the Boeing 767 type of aircraft into the Air Canada fleet . . . weight calculations were made in pounds, an Imperial measurement. When the new aircraft were ordered, a decision was taken, in line with Canadian government policy, to order them with their fuel gauges reading in kilograms, a metric measurement. Similarly, calculations of takeoff weight of the new type of aircraft were to be made in kilograms.

Critical to the determination of the correct fuel quantity by the drip stick method is the conversion from centimeters to litres and from liters to kilograms. The first part is easy because drip tables are provided and kept on board the aircraft. The drip tables, as they existed at the time of the Gimli accident, provided a simple means of converting centimeters to litres. On the other hand, converting from litres to kilograms involves using a conversion factor. At the time, the conversion factor was called specific gravity. The term, as used to describe the conversion factor of 1.77 lbs per liter is a misnomer. The term, however, has been used in the aircraft industry throughout the world for a long time. Unfortunately, the conversion factor or specific gravity as it was mistakenly called, supplied to those making the calculations in Montreal and Ottawa was 1.77. This is the figure to convert litres to pounds. The conversion factor to convert litres to kilograms is typically around .8.

Source: Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident, Part II

The ground crew dipped the tanks and determined there was 7,682 liters of fuel on the airplane. The crew then used the incorrect conversion factor of 1.77 kilograms per liter to determine the airplane had (7682)(1.77) = 13,597 kg of fuel on board. Since they needed 22,300 kg to fly the trip, they ordered (22,300 - 13,597) = 8,703 kg of fuel. They used the same factor to compute 8,703 / 1.77 = 4,916 liters of fuel to fly the trip.

The correct factor was 0.80 kg/liter, which meant they only had (7682)(0.803) = 6,669 kg of fuel on board. They needed 22,300 - 6,6169 - 16,121 kg to fly the trip and should have ordered 16,131 / 0.803 = 20,088 liters of fuel to fly the trip. They uploaded about a quarter of the fuel needed. Instead of having 22,300 kilograms of fuel, they had 22,300 pounds (10,100 kilograms). They had half the fuel they needed.

The first signs of trouble appeared shortly after 8:00 p.m. Central Daylight Time when instruments in the cockpit warned of low fuel pressure in the left fuel pump. The Captain at once decided to divert the flight to Winnipeg, then 120 miles away, and commenced a descent from 41,000 feet. Within seconds, warning lights appeared indicating loss of pressure in the right main fuel tank. Within minutes, the left engine failed, followed by failure of the right engine. The aircraft was then at 35,000 feet, 65 miles from Winnipeg and 45 miles from Gimli.

Fortunately for all concerned, one of [the captain's] skills is gliding. He proved his skill as a glider pilot by using gliding techniques to fly the large aircraft to a safe landing.

Source: Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident, Part II

4

Cause

- The responsibility for the miscalculation of the fuel load on Flight 143 on July 23, 1983 has to be borne both by the flight crew and the maintenance personnel involved, particularly those in Montreal.

- The fact that Flight 143 took off from Montreal on July 23, 1983 with blank fuel gauges was a significant cause of the accident. It was an illegal dispatch contrary to the provisions of the Minimum Equipment List.

Source: [Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident, Part III]

5

Postscript

The lessons here are obvious:

- Be paranoid about fuel, especially when unfamiliar with the units being used.

- Do not accept an MEL deferral at face value, research it yourself and come to fully understand the implications.

- Do not accept a "higher authority" decision about what you can and cannot accept when assuming the responsibility for the safe conduct of a flight. (It appears the captain's claim of a higher authority directive may have been made up, the but the lesson is still a good one.)

An interesting side note. I like watching the U.K. television series Mayday for recreations of these mishaps. The captain and first officer granted the series interviews and were treated very kindly, with only a one sentence note that they "were partly blamed for their roles in the incident." In fact, the captain was demoted for six months and the first officer was suspended for two weeks. The Canadian Transportation Safety Board cited Air Canada for failing to train the pilots to make the proper fuel calculations while praising the crew for overcoming the problems caused by "corporate and equipment deficiencies. Two years later both were awarded the first ever Fédération Aéronautique Internationale Diploma for Outstanding Airmanship.

Outstanding airmanship? I would give them an award for outstanding stick and rudder skills but then I would take away their licenses for very poor airmanship. The primary ingredient in airmanship, after all, is judgement.

References

(Source material)

Final Report of the Board of Inquiry into Air Canada Boeing 767 C-GAUN Accident - Gimli, Manitoba, July 23, 1983, Government of Canada

Flight Safety Australia, The 156-tonne Gimli Glider, July-August 2003

Mayday: Gimli Glider, Cineflix, Episode 37, Season 5, 14 May 2002 (Air Canada 143)