This could have been the worst aviation accident of all time, not just another case of a wrong surface landing attempt. After reading this case study, you should be convinced of the need to always have some kind of electronic situational awareness tool available for every approach and landing, especially those at night.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-12-21

Air Canada 759, NTSB AIR, figure 2.

The worst aviation accident of all time? If you don't believe me, watch this surveillance video of Air Canada 759's approach: Air Canada 759 SFO approach. Keep in mind there were five airplanes and over 1,000 people at risk.

1

Accident report

- Date: 7 July 2017

- Time: 23:57

- Type: Airbus A320-11

- Operator: Air Canada

- Registration: C-FKCK

- Fatalities: 0 of 5 crew, 0 of 135 passengers

- Aircraft fate: No damage

- Phase: Approach

- Airport (departure): Toronto-Pearson International Airport, ON, Canada (CYYZ)

- Airport (arrival): San Francisco International Airport CA, USA (KSFO)

2

Narrative

Several of my Air Force squadrons were involved with landings on the wrong airport, wrong runway, or wrong surfaces. Most of those were on clear days but a few were at night. We had a rule in most of those squadrons that the first approach into an unfamiliar airport should be off a precision approach.

I've flown into KSFO at night many times and I always had some kind of course guidance in view. A lot has been made about the messed up NOTAMS and they were, as the head of the NTSB said, a bunch of garbage. But the real culprit, I believe, is that the pilots seemed to be in the habit of not looking at course guidance when flying a visual approach.

- On July 7, 2017, about 2356 Pacific daylight time (PDT), Air Canada flight 759 (ACA759), an Airbus A320-211, Canadian registration C-FKCK, was cleared to land on runway 28R at San Francisco International Airport (SFO), San Francisco, California, but instead lined up with parallel taxiway C. Four air carrier airplanes (a Boeing 787, an Airbus A340, another Boeing 787, and a Boeing 737) were on taxiway C awaiting clearance to take off from runway 28R. The incident airplane descended to an altitude of 100 ft above ground level (agl) and overflew the first airplane on the taxiway. The incident flight crew initiated a go-around, and the airplane reached a minimum altitude of about 60 ft and overflew the second airplane on the taxiway before starting to climb. None of the 5 flight crewmembers and 135 passengers aboard the incident airplane were injured, and the incident airplane was not damaged. The incident flight was operated by Air Canada under Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 129 as an international scheduled passenger flight from Toronto/Lester B. Pearson International Airport (YYZ), Toronto, Canada. An instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan had been filed. Night visual meteorological conditions (VMC) prevailed at the time of the incident.

- One of the NOTAMs in the dispatch release indicated that runway 28L would be closed from 2300 that night to 0800 the next morning. During postincident interviews, both flight crewmembers provided different accounts regarding their awareness of the runway closure. During interviews about 1 week after the incident, the captain stated that he saw the NOTAM about the runway 28L closure in the flight release, and the first officer stated that he did a “quick scan” of the NOTAMs in the flight release but could not recall whether he had seen the runway 28L closure NOTAM and whether he and the captain had discussed the closure information at the gate. The first officer also stated that he realized, after the incident flight landed, that runway 28L had been closed. During an interview about 1 month after the incident, the captain stated that he and the first officer had discussed the runway 28L closure while at YYZ but that they did not place much emphasis on that information because, at that time, the flight was scheduled to land at SFO before the runway would be closed. (The National Transportation Safety Board [NTSB] notes that the flight was originally scheduled to land at SFO at 2303, 3 minutes after runway 28L was scheduled to be closed.)

- Before the airplane began its descent into the terminal area, the first officer obtained automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information Quebec via the airplane’s aircraft communication addressing and reporting system (ACARS) and printed the information. (Air Canada records indicated that, about 2321, the airplane was sent the ACARS message with the ATIS information.) Among other things, ATIS information Quebec indicated, “Quiet Bridge visual approach in use,” “landing runway 28R,” and “NOTAMS…runways 28L, 10R closed.” (SFO lighting logs indicated that the lights on runway 28L were turned off about 2312.) ATIS information Quebec also indicated that the runway 28L approach lighting system and the runway 28L/10R centerline lights were out of service. During postincident interviews, the flight crewmembers recalled reviewing ATIS information Quebec but could not recall whether they saw the ATIS-reported information about the runway 28L closure.

- ATIS information Quebec also included weather information. Given this information and the reported landing runway in use, the captain briefed Air Canada’s Flight Management System (FMS) Bridge visual approach procedure to SFO runway 28R. The FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R, coded as the area navigation (RNAV) 28R approach, was a commercial airline overlay chart (a Jeppesen chart customized for Air Canada) based on the Quiet Bridge visual approach procedure to runway 28R.

- Air Canada’s FMS Bridge visual approach procedure to runway 28R required pilots of Airbus A319/A320/A321 airplanes to manually enter (tune) the instrument landing system (ILS) frequency into the airplane’s flight management computer (FMC) to provide backup lateral guidance (via the localizer) to the runway. The FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R was the only approach in Air Canada’s Airbus A320 database that required manual tuning for a navigational aid. As part of his pilot monitoring duties, the first officer would have used the multifunction control and display unit (MCDU) to program required settings, but he did not enter the ILS frequency into the radio/navigation page. The first officer reported, during a postincident interview, that he “must have missed” the radio/navigation page and was unsure how that could have happened. Also, the captain did not verify, during the approach briefing, that the ILS frequency had been entered, and neither flight crewmember noticed that the ILS frequency was not shown on the primary flight displays (PFD). FDR data showed that the ILS frequency was not tuned and that no frequency had been entered.

- As part of the approach briefing, Air Canada’s procedures required the flight crew to discuss any threats associated with the approach. The captain stated that they discussed as threats the nighttime landing, the traffic, and the busy airspace. The captain also reported that he and the first officer discussed that “it was getting late” and that they would need to “keep an eye on each other.” The first officer stated that the threats were the mountainous terrain, the nighttime conditions, and both flight crewmembers’ alertness. The captain and the first officer could not recall whether they discussed the runway 28L closure during the approach briefing.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1

I adopted the threat-based briefing a few years ago but have noticed it has become rote. That is, we tend to say things like "Threats? Oh, it is a night landing into a busy airport" and then we move onto the next item in our briefing checklist. I'm not sure how to best solve this problem. I am toying with the idea of replacing "Threats?" with "What can go wrong?"

- According to air traffic control (ATC) voice recordings, at 2330:42, the flight crew checked in with the Northern California terminal radar approach control (NCT) approach controller on the DYAMD 3 (RNAV) standard terminal arrival route to SFO. At that time, the airplane was descending from an altitude of 27,000 ft msl.

- After the flight crew’s initial contact with NCT, the controller issued instructions to join the FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R after reaching the final waypoint on the standard terminal arrival route. FDR data showed that, as the airplane descended through an altitude of about 14,500 ft msl at 2336:30, the altitude selected parameter changed to 10,944 ft msl. At 2338:01, the autopilot lateral navigation mode changed from “NAV” to “HDG [heading]” with no recorded corresponding change in the vertical navigation mode. According to Airbus, this configuration and the change in selected altitude were consistent with the autopilot operating in an open descent profile. The flight crewmembers did not discuss the descent mode during the approach briefing, but the first officer reported, during a postincident interview, that he perceived that the descent mode had switched from a managed to an open descent. The first officer also stated that he was uncomfortable with the approach being flown in the open descent mode and that he did not say anything to the captain because the procedure was allowed.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1

Proponents of more hand-flying will tell you that sometimes you need to lower the level of automation to make things safe. I think that sometimes we lower the level of automation because it is easier than managing a non-standard FMS procedure. It is also more comfortable for the pilot, in that once hand-flying you have an excuse to stop thinking strategically. I will fire the autopilot now and then, but when I do, I often think it was a failure in my part because I put the airplane into a situation it couldn't cope with. In this particular situation, keeping the autopilot in control of lateral course guidance frees the PF to think ahead of the airplane and frees the PM to monitor other things than keeping a watchful eye on the PF's stick and rudder skills.

- At 2346:08, the controller instructed ACA759 to turn right direct to the TRDOW waypoint and join the FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R, and the flight crew acknowledged this instruction. At 2346:19, the controller asked the crewmembers if they had the airport or bridges in sight; the flight crew replied that the bridges were in sight. At 2346:30, the controller cleared the airplane for the approach and, at 2350:48, instructed the flight crew to contact the SFO air traffic control tower (ATCT).

- At 2351:07, the flight crew contacted the SFO ATCT and advised that the airplane was on the FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R. Four seconds later, the tower controller issued a landing clearance for runway 28R. The flight crew acknowledged the landing clearance at 2351:18. FDR data showed that the landing gear was selected to the down position at 2352:46.

- Air Canada’s FMS Bridge visual approach procedure to runway 28R indicated that pilots of Airbus A319/A320/A321 airplanes were to do the following: “at or before F101D [the final waypoint on the approach], disengage autopilot and continue as per Visual Approaches [standard operating procedures].” FDR data showed that the autopilot was disconnected at 2353:28 when the airplane was at an altitude of 1,300 ft and that the flight directors were disengaged at 2354:02 when the airplane was at an altitude of 1,200 ft. The airplane passed F101D at 2354:28, when the airplane was at an altitude of about 1,100 ft, and the captain made the required 14° right turn to align the airplane with runway 28R but instead aligned the airplane with taxiway C.

- During a postincident interview, the first officer reported that, during the approach, he was looking inside the cockpit to accomplish his tasks as the pilot monitoring. For example, after the autopilot was disconnected, the first officer set the missed approach altitude and heading in case a missed approach was necessary; the first officer stated that he had to look at the approach chart to obtain that information. Also, the first officer reported that the captain had asked him to set the heading bug (indicator) to the runway heading. The first officer stated that he had difficulty finding the heading information on the approach chart, so he had to reference the airport chart. The captain reported that he saw lights across what he thought was the runway 28R surface. The captain asked the first officer to find out whether the runway was clear, at which time the first officer looked outside the cockpit. The first officer stated that the captain’s request occurred between the time that the airplane passed F101D (at an altitude of about 1,100 ft) and the time that the airplane descended to an altitude of 600 ft.

- The ATC voice recording indicated that, at 2355:45, the flight crew made the following transmission to the controller: “Just want to confirm, this is Air Canada seven five nine, we see some lights on the runway there, across the runway. Can you confirm we’re cleared to land?” At that time, the airplane was passing through an altitude of 300 ft. During a postincident interview, the controller stated that, just before the query about the status of runway 28R, he had visually scanned the runways from the departure to approach ends. The controller also stated that, in response to the query, he checked the radar display and the airport surface surveillance capability (ASSC) display and then rescanned runway 28R. Regarding the ASSC display, the controller reported that he saw the ACA759 data symbol just to the right of the runway centerline, which he stated was normal for the FMS Bridge visual approach to runway 28R.

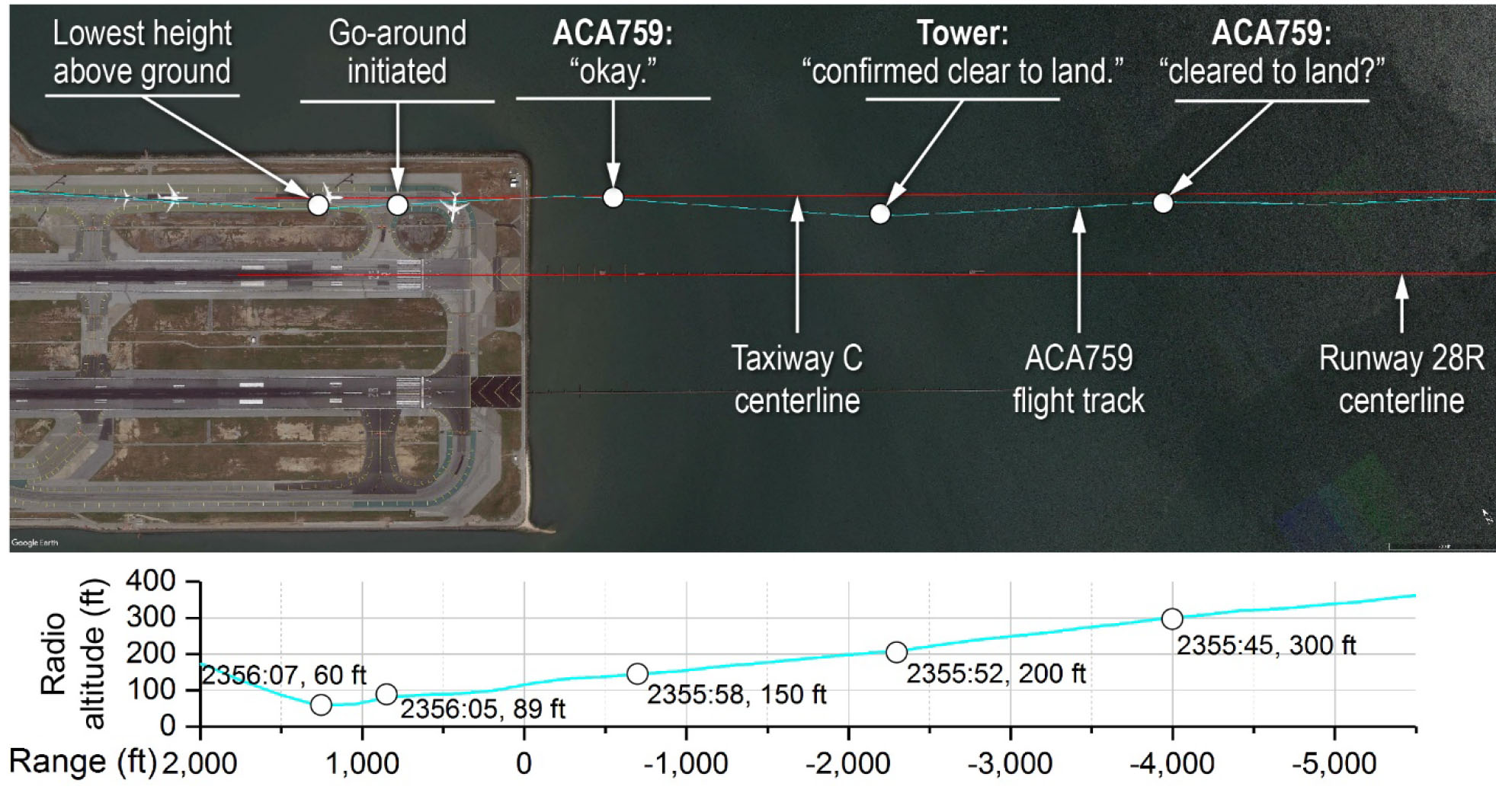

- At 2355:52, 1 second after the flight crew completed its transmission, the controller replied, “Air Canada seven five nine confirmed cleared to land runway two eight right. There’s no one on runway two eight right but you.” About that time, the airplane was passing through an altitude of 200 ft and was 2,300 ft (0.38 nautical mile [nm]) from the seawall that protected the airfield from San Francisco Bay. At 2355:58, the flight crew acknowledged the transmission; about that time, the airplane was 500 ft (0.08 nm) from the seawall. Figure 1 shows ACA759’s track before reaching the seawall along with the extended centerlines for runway 28R and taxiway C.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1

Air Canada 759 track over SFO, NTSB AIR, figure 1.

- The ATC voice recording also indicated that, at 2355:59, another pilot stated on the tower frequency, “where is that guy going?” The voice on the transmission was later identified as that of the captain from the first airplane on taxiway C, United Airlines flight 1 (UAL1). About that time, ACA759 was still 500 ft (0.08 nm) from the airport seawall and at an altitude of 150 ft while lined up with taxiway C. At 2356:03 (after ACA759 crossed the seawall), ACA759 overflew UAL1 at an altitude of 100 ft; about the same time, the UAL1 captain stated, over the tower frequency, “he’s on the taxiway.” About the same time as the UAL1 captain’s second transmission, the flight crew from the second airplane on taxiway C, Philippine Airlines flight 115 (PAL115), turned on that airplane’s landing gear and nose lights, illuminating a portion of the taxiway and the UAL1 airplane.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1

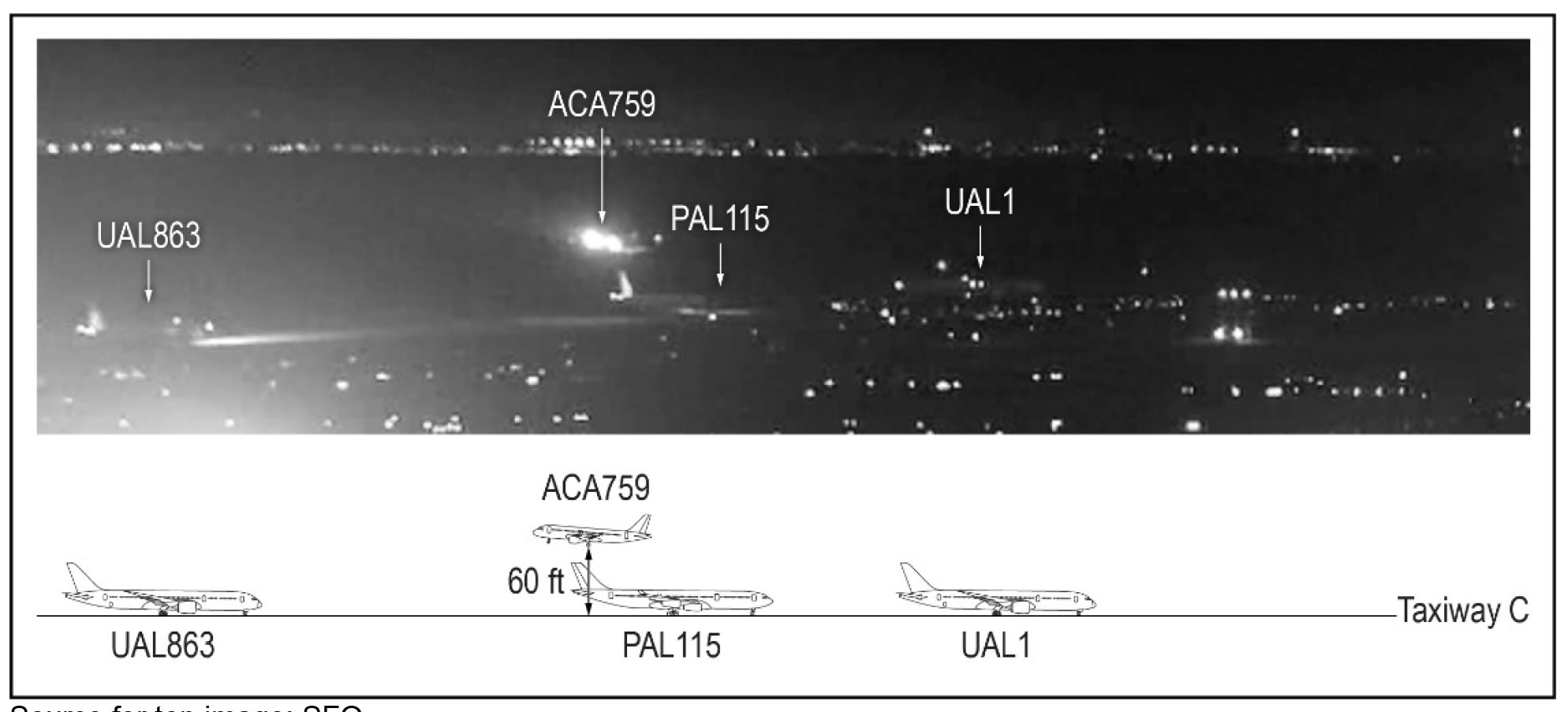

The actions of the pilots on UAL 1 and PAL115 saved hundreds of lives.

- FDR data showed that, at 2356:05, the throttles on ACA759 were advanced, and the airplane’s engine power and pitch increased. At that time, the airplane was at an altitude of about 89 ft. During a postincident interview, the captain stated that, as the airplane was getting ready to land, “things were not adding up” and it “did not look good,” so he initiated a go-around. The captain reported that he thought that he saw runway lights for runway 28L and believed that runway 28R was runway 28L and that taxiway C was runway 28R. During a postincident interview, the first officer reported that he thought that he saw runway edge lights but that, after the tower controller confirmed that the runway was clear, he then thought that “something was not right”; as a result, the first officer called for a go-around because he could not resolve what he was seeing. The captain further reported that the first officer’s callout occurred simultaneously with the captain’s initiation of the go-around maneuver.

- The airplane continued descending, reaching a minimum altitude of about 60 ft at 2356:07 as the airplane overflew PAL115. One second later, once the engines and elevators had fully transitioned to their go-around position, the airplane began to climb. During the 3 seconds between the time that the flight crew initiated the go-around and the airplane began climbing, ACA759 had flown about 700 ft (0.12 nm) from the location over the taxiway where the go-around was initiated.

- At 2356:09, the controller instructed the ACA759 flight crew to go around. The ACA759 flight crew acknowledged this instruction 2 seconds later as the airplane overflew the third airplane on the taxiway, United Airlines flight 863 (UAL863), at an altitude of 200 ft. Immediately afterward, ACA759 overflew the fourth airplane on the taxiway, United Airlines flight 1118 (UAL1118) at an altitude of 250 ft. Both incident pilots reported (during postincident interviews) that they did not see any airplanes on the taxiway.

- At 2356:12, the controller advised the ACA759 flight crew, “it looks like you were lined up for [taxiway] Charlie,” and instructed ACA759 to fly a heading of 280° and climb to 3,000 ft msl. The flight crew acknowledged the heading and altitude instructions at 2356:18. At 2356:23, ACA759’s landing gear was raised; 5 seconds later, the autopilot was engaged. At 2356:44 and 2356:55, the controller instructed the flight crew to contact NCT, and the crew acknowledged the instruction at 2357:00. During the downwind leg for ACA759’s second approach, the first officer asked the captain if they should set the ILS frequency, and the captain agreed. The second approach to SFO was uneventful, and ACA759 made a successful landing on runway 28R about 0011 on July 8. The captain and first officer completed their duty periods at 0032.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1

The NOTAMS

A lot has been made of the fact the NOTAMS included the runway closure. Here is what the NOTAMS said that night:

!SFO 11/095 SFO RWY 28R DECLARED DIST: TORA 11870FT TODA 11870FT ASDA 11870FT LDA 11236FT. 1611220012-PERM

!SFO 11/094 SFO RWY 28L DECLARED DIST: TORA 11381FT TODA 11381FT ASDA 10981FT LDA10275FT. 1611220012-PERM

!SFO 04/189 SFO TWY S2 BTN TWY Z AND TWY S3 CLSD TO ACFT WINGSPAN MORE THAN 215FT1604291657-PERM

!SFO 05/248 SFO TWY N CL LGT BTN TWY F AND RWY 10L/28R OUT OF SERVICE 1705291227-PERM

!SFO 11/011 SFO APRON TAXILANE H1 CLSD 1611040934-PERM

!FDC 5/7988 SFO CANCELLED BY FDC 6/0989 ON 10/16/16 00:00

!FDC 7/6636 SFO IAP SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. RNAV (GPS) Z RWY 28R, AMDT 5A...LPV DA VISIBILITY RVR 1800 ALL CATS. THIS IS RNAV (GPS) Z RWY 28R, AMDT 5B. 1706212031-PERM

!FDC 7/6632 SFO IAP SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. RNAV (GPS) RWY 28L, AMDT 5A...CHART NOTE: ASTERISK, ASTERISK RVR 1800 AUTHORIZED WITH USE OF FD OR AP OR HUD TO DA. CHANGE LPV DA TO LPV DA ASTERISK, ASTERISK. THIS IS RNAV (GPS) RWY 28L, AMDT 5B. 1706212029-PERM

!SFO 02/024 SFO OBST CRANE 2016-AWP-3215-NRA 373656N1222304W (1500FT W APCH END RWY 01L) 133FT (125FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1702031340-2208031340

!SFO 02/023 SFO OBST CRANE 2016-AWP-3080-NRA 373654N1222303W (1500FT W APCH END RWY 01L) 133FT (125FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1702031340-2208031340

!SFO 02/025 SFO OBST CRANE 2016-AWP-3216-NRA 373650N1222318W (1500FT W APCH END RWY 01L) 133FT (125FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1702031340-2208031340

!SFO 02/026 SFO OBST CRANE 2016-AWP-3217-NRA 373643N1222311W (1500FT W APCH END RWY 01L) 133FT (125FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1702031340-2208031340

!SFO 02/027 SFO OBST CRANE 2016-AWP-3218-NRA 373648N1222258W (1500FT W APCH END RWY 01L) 133FT (125FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1702031340-2208031340

!SFO 10/047 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2427-OE) 373536N1222306W (1.6NM SSW SFO) 100FT (61FT AGL) LGTD 1610112035-1804112300

!SFO 03/212 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2987-NRA) 373724N1222352W (1.1NM WNW SFO) 251FT (245FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1703242254-1712161200

!SFO 03/213 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2988-NRA) 373724N1222353W (1.1NM WNW SFO) 251FT (245FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1703242255-1712161200

!SFO 03/214 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2989-NRA) 373723N1222353W (1.1NM WNW SFO) 251FT (245FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1703242300-1712161200

!SFO 03/215 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2990-NRA) 373723N1222355W (1.1NM WNW SFO) 251FT (245FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1703242308-1712161200

!SFO 03/216 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2991-NRA) 373722N1222356W (1.1NM WNW SFO) 251FT (245FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1703242308-1712161200

!FDC 6/7354 SFO STAR SAN FRANCISCO INTL., SAN FRANCISCO, CA. BIG SUR THREE ARRIVAL...FROM OVER ANJEE INT CHANGE MINIMUM HOLDINGALTITUDE TO READ: 11000FT. 1612061900-1712052359EST

!FDC 6/7361 SFO STAR SAN FRANCISCO INTL., SAN FRANCISCO, CA. BIG SUR THREE ARRIVAL...FROM OVER BSR VORTAC TO CARME, THENCE FROM OVER CARME TO ANJEE INT REVISE MINIMUM EN ROUTE ALTITUDE TO READ: 11000FT. 1612061900-1712052359EST

!SFO 04/069 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-2357-NRA) 373703N1222260W (0.4NM WSW SFO) 251FT (240FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1704100700-1711301200

!FDC 6/9114 SFO STAR SAN FRANCISCO INTL, SAN FRANCISCO, RISTI FOUR ARRIVAL ADD NOTE TO READ: PROPS AND TURBO PROPS ONLY. 1611162030-1711152359

!FDC 6/9115 SFO STAR SAN FRANCISCO INTL., SAN FRANCISCO, CA. POINT REYES TWO ARRIVAL SAC VORTAC TO POPES INT, MEA 5100. 1611162030-1711152359EST

!FDC 7/5661 SFO SID SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. SSTIK THREE DEPARTURE (RNAV)... WESLA THREE DEPARTURE (RNAV)...YYUNG TRANSITION NA. ALL OTHER DATA REMAINS AS PUBLISHED. 1704051317-1711151317EST

!SFO 07/029 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-1309-OE) 373960N1222356W (3.1NM NNW SFO) 372FT (298FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1607071857-1711100100

!FDC 7/2076 SFO ODP SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. TAKEOFF MINIMUMS AND (OBSTACLE) DEPARTURE PROCEDURES AMDT 9...TAKEOFF MINIMUMS: RWY 28L, 28R, STANDARD WITH A MINIMUM CLIMB OF 415FT PER NM TO 1300. ADD NOTE: RWY 19R, TEMPORARY CRANE 935FT FROM DER, 609FT RIGHT OF CENTERLINE, 125FT AGL/135FT MSL (2016-AWP-2003-NRA). RWY 28L, TEMPORARY CRANE 1.39 NM FROM DER, 2831FT LEFT OF CENTERLINE, 350FT AGL/ 448FT MSL (2016-AWP-10862-OE). RWY 28R, TEMPORARY CRANES BEGINNING 3043FT FROM DER, 762FT RIGHT OF CENTERLINE, UP TO 120FT AGL/ 131FT MSL (2015-AWP-1790-NRA, 2015-AWP-1839 THROUGH 1842-NRA). TEMPORARY CRANE 1.31 NM FROM DER, 3581FT LEFT OF CENTERLINE, 350FT AGL/ 448FT MSL (2016-AWP-10862-OE). ALL OTHER DATA REMAINS AS PUBLISHED. 1703291326-1711081326EST

!FDC 7/2077 SFO SID SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. GAP SEVEN DEPARTURE... MOLEN EIGHT DEPARTURE... OFFSHORE ONE DEPARTURE... SAN FRANCISCO FOUR DEPARTURE... TAKEOFF MINIMUMS: RWY 28L, 28R, STANDARD WITH A MINIMUM CLIMB OF 415FT PER NM TO 1300. ADD TAKEOFF OBSTACLE NOTE: RWY 19R, TEMPORARY CRANE 935FT FROM DER, 609FT RIGHT OF CENTERLINE, 125FT AGL/ 135FT MSL (2016-AWP-2003-NRA). RWY 28L, TEMPORARY CRANE 1.39 NM FROM DER, 2831FT LEFT OF CENTERLINE, 350FT AGL/ 448FT MSL (2016-AWP-10862-OE). RWY 28R, TEMPORARY CRANES BEGINNING 3043FT FROM DER, 762FT RIGHT OF CENTERLINE, UP TO 120FT AGL/ 131FT MSL (2015-AWP-1790-NRA, 2015-AWP-1839 THROUGH 1842-NRA). TEMPORARY CRANE 1.31 NM FROM DER, 3581FT LEFT OF CENTERLINE, 350FT AGL/ 448FT MSL (2016-AWP-10862-OE). ALL OTHER DATA REMAINS AS PUBLISHED. 1703291326-1711081326EST

!FDC 7/9012 SFO IAP SAN FRANCISCO INTL, SAN FRANCISCO, CA. ILS OR LOC RWY 28L, AMDT 25A ... ILS RWY 28L (SA CAT II), AMDT 25A ... TERMINAL ROUTE ARCHI (IAF) TO PONKE/I-SFO 21.6 DME MINIMUM ALTITUDE 6000 1702282122-1710102119EST

!SFO 03/277 SFO OBST RIG (ASN UNKNOWN) 373723N1222353W (1.16NM WNW SFO) 96FT (86FT AGL) FLAGGED 1703311400-1710020001

!SFO 06/142 SFO APRON TXL M1, M2 CLSD 1706261717-1709010700

!SFO 05/132 SFO RWY 10R/28L NOT GROOVED 1705172226-1709010500

!FDC 7/0273 SFO CA..SPECIAL NOTICE..SAN FRANCISCO INTERNATIONAL, CALIFORNIA, RWY STATUS LGTS ARE IN AN OPR TEST ON RWY 10L/28R, RWY 10R/28L, RWY 01L/19R, RWY 01R/19L AND MUST BE COMPLIED WITH. RWY STATUS LGT ARRAYS MAY BE OFFLINE INTERMITTENTLY THROUGHOUT THE TEST PHASE. RWY STATUS LGTS ARE RED IN-PAVEMENT LGTS THAT SERVE AS WARNING LGTS ON RWYS AND TWYS INDICATING THAT IT IS UNSAFE TO ENTER, CROSS, OR BEGIN TKOF ON A RWY. NOTE: RWY STATUS LGTS INDICATE RWY STATUS ONLY. THEY DO NOT INDICATE CLEARANCE. PILOTS AND VEHICLE OPRS MUST STILL RECEIVE A CLEARANCE FROM AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL BEFORE PROCEEDING. FOR ADDITIONAL INFORMATION VISIT: HTTP://WWW.FAA.GOV/AIR_TRAFFIC/TECHNOLOGY/RWSL 1705231700-1708302359

!SFO 04/166 SFO TWY J CLSD 1704140651-1708012359

!SFO 02/057 SFO OBST CRANE (ASN 2016-AWP-74-NRA) 373644N1222308W (0.6NM SW SFO) 158FT (150FT AGL) FLAGGED AND LGTD 1602111446-1708012300

!SFO 04/167 SFO TWY J CL LGT OUT OF SERVICE 1704140651-1708011200

!SFO 03/164 SFO APRON TAXILANE M CL LGT OUT OF SERVICE 1703211939-1707311300

!FDC 7/5705 SFO IAP SAN FRANCISCO INTL, San Francisco, CA. RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 10R, AMDT 2A... RNP 0.20 DA 409/ HAT 399 ALL CATS. TEMPORARY CRANES UP TO 131 MSL BEGINNING 3980FT NORTHWEST OF RWY 10R (2015-AWP-1790-NRA, 2015-AWP-1839 THROUGH 1842-NRA). 1704051332-1707301332EST

!FDC 7/5704 SFO SID SAN FRANCISCO INTL, SAN FRANCISCO, CA. AFIVA ONE DEPARTURE (RNAV)... GNNRR TWO DEPARTURE (RNAV)... NIITE THREE DEPARTURE (RNAV)... OFFSHORE ONE DEPARTURE... SAN FRANCISCO FOUR DEPARTURE... SNTNA TWO DEPARTURE (RNAV)... TRUKN TWO DEPARTURE (RNAV)... WESLA THREE DEPARTURE (RNAV)... ADD TAKEOFF OBSTACLE NOTE: RWY 28R, TEMPORARY CRANES BEGINNING 3043FT FROM DER, 762FT RIGHT OF CENTERLINE, UP TO 120FT AGL/ 131FT MSL (2015-AWP-1790-NRA, 2015-AWP-1839 THROUGH 1842-NRA). ALL OTHER DATA REMAINS AS PUBLISHED. 1704051331-1707301331EST

!SFO 06/018 SFO NAV ILS RWY 28L CAT II NA 1706021405-1707211500

!SFO 06/017 SFO RWY 28L ALS OUT OF SERVICE 1706021357-1707211500

!SFO 07/032 SFO OBST TOWER LGT (ASR 1205149) 374114.40N1222605.30W (5.1NM NW SFO) 1566.9FT (311.0FT AGL) OUT OF SERVICE 1707072337-1708072337

!SFO 07/031 SFO TWY D BTN RWY 10R/28L AND TWY B CLSD 1707101330-1707101800

!SFO 07/030 SFO RWY 10L/28R CLSD 1707100700-1707101430

!SFO 07/027 SFO RWY 10L/28R CLSD 1707090300-1707091500

!SFO 07/028 SFO RWY 01R/19L CLSD 1707090300-1707091500

!SFO 07/025 SFO RWY 01R/19L CLSD 1707080600-1707081500

!SFO 07/026 SFO RWY 10R/28L CLSD 1707080600-1707081500

!SFO 07/033 SFO NAV ILS RWY 28L OUT OF SERVICE 1707080600-1707081500

3

Analysis

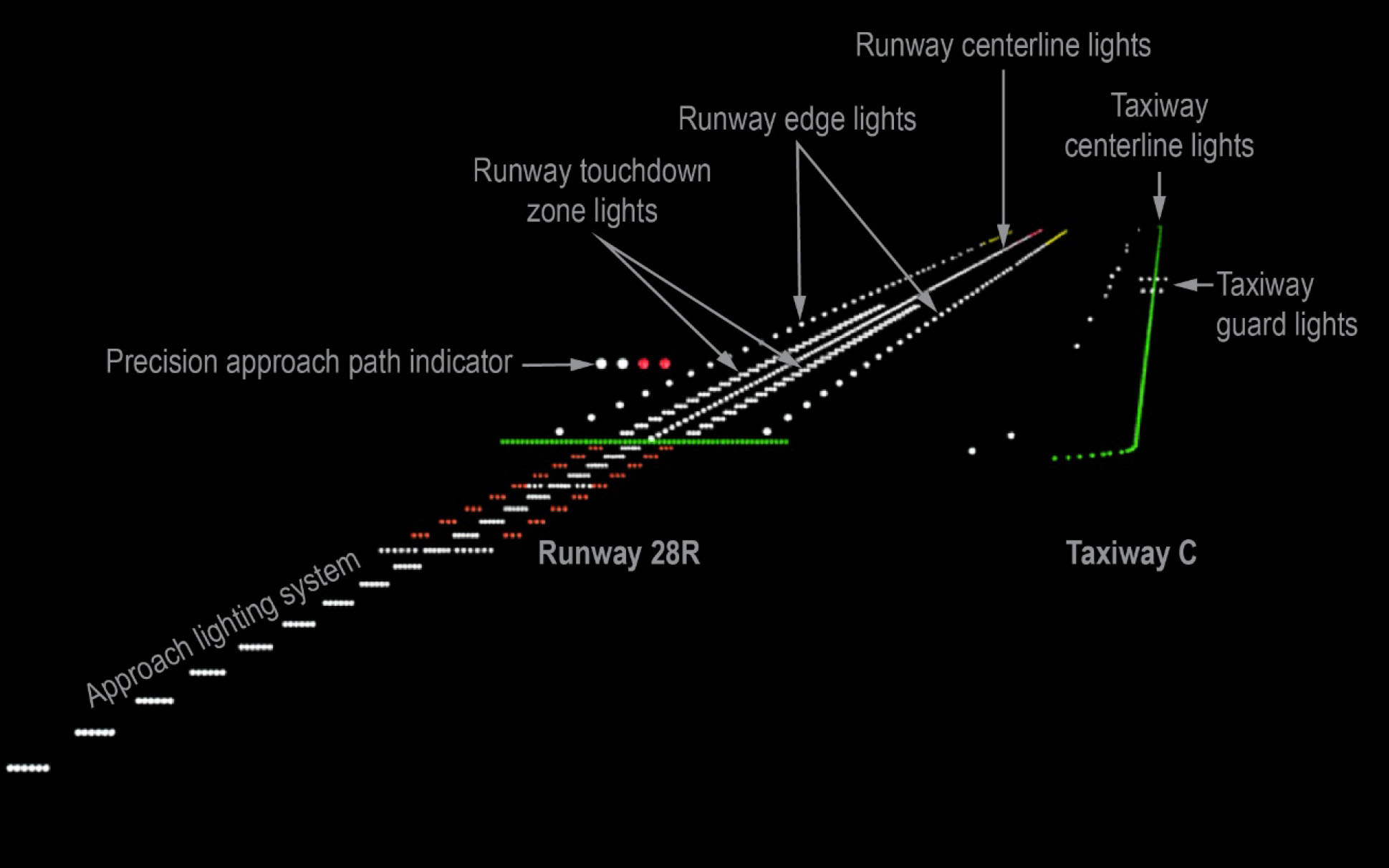

The incident pilots screwed up, no doubt about it. But it isn't as cut and dried as that. Landing at night on either of the Runways 28 at San Francisco can be a visual challenge. You are descending over San Francisco Bay which becomes a black hole at night. On a clear night, the tower will likely have the approach lighting system somewhat dim. The photo illustration (figure 4, shown) isn't what the pilots saw. What they saw would have been the opposite, a bright set of lights on the taxiway and a dim set on the runway.

The report makes a big deal of the fact the PM forgot to set the ILS frequency and the PF didn't catch that. It appears to me these pilots were not in the habit of referencing their instruments on a visual approach since neither noticed the needles were not giving course guidance. Therein lies the problem: the pilots routinely flew visual approaches without taking advantage of all situational awareness tools.

Air Canada 759 on final approach, NTSB AIR, figure 6

- The airplane that preceded the incident airplane into SFO, a Boeing 737 operated as Delta Air Lines flight 521 (DAL521), landed on runway 28R about 4 minutes before the incident occurred. During postincident interviews, both DAL521 flight crewmembers reported that, after visually acquiring the runway environment, they questioned whether their airplane was lined up for runway 28R. The DAL521 captain stated that he could see lights (but no airplanes) on taxiway C and that those lights gave the impression that the surface could have been a runway. The DAL521 first officer reported seeing a set of lights to the right of runway 28R but that he “could not register” what those lights were. The DAL521 first officer also reported that there were “really bright” white lights on the left side of runway 28R (similar to the type used during construction), but both he and the captain knew that runway 28L was closed.

- The DAL521 flight crewmembers were able to determine that their airplane was lined up for runway 28R after cross-checking the lateral navigation (LNAV) guidance. The DAL521 captain stated that, without lateral guidance, he could understand how the runway 28R and taxiway C surfaces could have been confused because the lights observed on the taxiway were in a straight line and could have been perceived as a centerline. The DAL521 crewmembers confirmed that their airplane was lined up correctly when they visually acquired the painted “28R” marking on the paved surface of the runway; they estimated that their airplane was at an altitude of 300 ft at that time.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.1.1

Illustration of SFO (Runway 28R) lighting configuration, NTSB AIR, figure 4.

The airport light status (on/off) and intensity were controlled from the ATCT. Runway 28R was equipped with white runway edge lights, white centerline lights, white touchdown zone lights, and an approach lighting system with white centerline sequenced flashing lights (ALSF-2). Runway 28R was also equipped with a four-light precision approach path indicator with a 3° glidepath that was located on the left side of the runway. Taxiway C was equipped with green centerline lights that were spaced at 50-ft intervals (± 5 ft), blue taxiway edge lights located at the intersections with runway 28R to highlight the edge of the intersections, and flashing yellow in-pavement guard lights located where taxiway C intersected runway 1R/19L (which ran perpendicularly to runways 28L and 28R and taxiway C). Figure 4 shows an illustration of the lighting on runway 28R and taxiway C. On the night of the incident flight, the runway and taxiway centerline lights were set at step 1 (out of 5).

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.4

Air Canada 759 crossing over United AL 1 and Philippines AL 115, NTSB AIR, figure 6.

The lowest adjusted radio altitude, which occurred when ACA759 passed over PAL115, was determined to be 60 ft, which was the height of the bottom of the landing gear above the ground. To confirm this altitude, the NTSB examined the image from the security camera video that showed ACA759 passing over PAL115 (figure 8). In that image, the vertical stabilizer of the PAL115 airplane (an A340) was well illuminated. The NTSB used known dimensions of an A340 vertical stabilizer to scale the image, measured the closest point between the two airplanes, and determined that measurement to be 13.5 ft. Because the security camera image of the airplanes was relatively small and pixilated, this measurement was estimated to be between 10 and 20 ft to account for the inherent uncertainty. In addition, this measurement assumed that ACA759 was directly above PAL115; the lateral separation could not be determined from the image of ACA759 passing over PAL115. The A340 airplane (including the vertical stabilizer) was reported to be 55 ft tall, so the altitude of the ACA759 fuselage as it passed over PAL115 would have been between 65 and 75 ft, which was consistent with the 60-ft adjusted radio altitude plus the 5-ft distance between the bottom of the landing gear and the bottom of the fuselage.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶1.5.1

- Air Canada standard operating procedures stated that descent preparation should be completed before the top of the descent and listed the tasks that needed to be completed. The pilot monitoring (in this case, the first officer) was to use the MCDU to reference the radio/navigation page and set navigational aids into the FMC and then check that the ILS identifier shown on the PFDs was correct. The pilot flying (in this case, the captain) was to review the approach programming in the MCDU and complete an approach briefing, which included verifying that the primary approach aid (ILS) identifier and frequency were properly set.

- ATIS information Quebec indicated that the Quiet Bridge visual approach was in use and that arriving airplanes would be landing on runway 28R. The flight crew used Air Canada’s FMS Bridge visual approach procedure, which was based on the Quiet Bridge visual approach procedure, for the approach to runway 28R. Air Canada’s FMS Bridge visual approach chart consisted of two pages. The first page showed the approach procedure and included the ILS frequency for runway 28R in the plan view. The second page of the approach chart was in text format and indicated that Airbus A319/A320/A321 pilots should tune the ILS for runway 28R, which would provide flight crews with backup lateral guidance (via the localizer aligned with the runway heading) during the approach. This lateral guidance would supplement the visual approach procedures.

- The first officer stated that, when he set up the approach in the FMC, he missed the step in the procedure to manually tune the ILS frequency, and FDR data showed that no ILS frequency had been entered for the approach. According to Air Canada personnel, the FMS Bridge visual approach was the only approach in the company’s Airbus A320 database that required manual tuning of an ILS frequency, which might have contributed to the first officer’s failure to input the frequency (as discussed below). However, the first officer’s error should have been caught by the captain as part of his verification of the approach setup during the approach briefing. If cockpit voice recorder (CVR) information had been available for this incident (as discussed further in section 2.4), the NTSB might have been better able to determine whether distraction, workload, and/or other factors contributed to the first officer’s failure to manually tune the ILS frequency and the captain’s failure to verify that the ILS frequency was tuned. The NTSB concludes that the first officer did not comply with Air Canada’s procedures to tune the ILS frequency for the visual approach, and the captain did not comply with company procedures to verify the ILS frequency and identifier for the approach, so the crewmembers could not take advantage of the ILS’s lateral guidance capability to help ensure proper surface alignment.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶2.2.2

The cockpit voice recorder on this airplane had a 2-hour continuous loop that had overwritten the flight by the time Air Canada became aware of the severity of the incident.

- The NTSB concludes that the flight crew’s failure to manually tune the ILS frequency for the approach occurred because (1) the FMS Bridge visual approach was the only approach in Air Canada’s Airbus A320 database that required manual tuning of a navigation frequency, so the manual tuning of the ILS frequency was not a usual procedure for the crew, and (2) the instruction on the approach chart to manually tune the ILS frequency was not conspicuous during the crew’s review of the chart. Although the incident flight was operating under 14 CFR Part 129, the approach chart that the flight crew used was originally developed by an air carrier operating under 14 CFR Part 121. Therefore, the NTSB recommends that the FAA work with air carriers conducting operations under 14 CFR Part 121 to (1) assess all charted visual approaches with a required backup frequency to determine the FMS autotuning capability within an air carrier’s fleet, (2) identify those approaches that require an unusual or abnormal manual frequency input, and (3) either develop an autotune solution or ensure that the manual tune entry has sufficient salience on approach charts. The NTSB notes that, after the incident, Air Canada revised its procedures so that the FMS Bridge approach to runway 28R would be flown as an instrument approach.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶2.2.2

- The flight crew had opportunities before the approach to learn about the runway 28L closure. The first opportunity occurred before the flight when the crewmembers received the flight release. Both crewmembers stated that they reviewed NOTAMs in the flight release. However, the first officer stated that he could not recall reviewing the specific NOTAM that addressed the runway 28L closure. Also, even though the captain stated that he saw the runway closure information, his actions in misaligning the airplane demonstrated that he did not recall that information when it was needed, and he thought that runway 28R was runway 28L. The second opportunity occurred in flight during the crewmembers’ preparations for the approach to runway 28R. Both crewmembers recalled reviewing ATIS information Quebec, which they received via an ACARS message in the cockpit, but neither crewmember recalled reviewing the specific NOTAM in the ATIS information that described the runway 28L closure.

- Because the flight crewmembers either did not review or could not recall the information about the runway 28L closure, they expected to see two parallel runways while on approach to SFO and further expected that they would need to fly the approach to the right-side surface. The flight crew’s recent experience flying into SFO would have reinforced these expectations. For example, when the first officer flew into SFO 2 nights before the incident, the airplane used for that flight landed on runway 28R at 2305, which was about 18 minutes before runway 28L was closed. Also, the captain stated that he had never seen runway 28L “dark” and that none of his previous landings at SFO occurred when a runway was closed.

- The NTSB concludes that, although the NOTAM about the runway 28L closure appeared in the flight release and the ACARS message that were provided to the flight crew, the presentation of the information did not effectively convey the importance of the runway closure information and promote flight crew review and retention.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶2.3.1

4

Cause

The NTSB list of causes is more about what and not why. In my opinion, the why of the incident was that the pilots were in the habit of flying visual approaches without using all of the situational awareness tools available to them and the airline didn't instill upon them the need to do so.

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this incident was the flight crew’s misidentification of taxiway C as the intended landing runway, which resulted from the crewmembers’ lack of awareness of the parallel runway closure due to their ineffective review of notice to airmen (NOTAM) information before the flight and during the approach briefing. Contributing to the incident were (1) the flight crew’s failure to tune the instrument landing system frequency for backup lateral guidance, expectation bias, fatigue due to circadian disruption and length of continued wakefulness, and breakdowns in crew resource management and (2) Air Canada’s ineffective presentation of approach procedure and NOTAM information.

Source: NTSB AIR, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Incident Report, NTSB/AIR-18/01, Taxiway Overflight, Air Canada Flight 759, Airbus A320-211, C-FKCK, San Francisco, California, July 7, 2017