The NTSB Report blames the crew for failing to manage their fuel and failure to communicate their low fuel state with the specific word "emergency." The Federal Aviation Administration was cited for inadequate traffic flow management and a lack of "standardized understandable terminology for pilots and controllers for minimum and emergency fuel states." The crew was also cited for mishandling the first approach under windshear conditions.

— James Albright

Updated:

2016-08-03

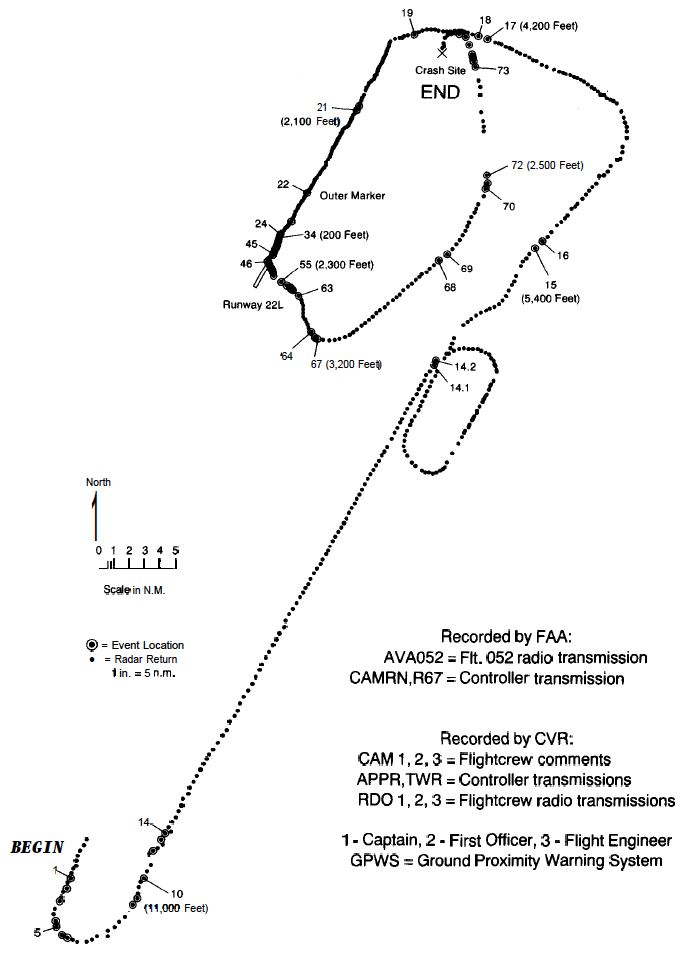

AVA052 Flight Reconstruction,

from NTSB AAR-91/04, Figure 1.

There is much to cover here but I'll not cover the windshear issue. It is true that had they managed to land on the first approach the accident would never have happened. But there is much more to learn here about communications between aircraft and aircraft control. I do believe the pilots could have managed their situation better and should have declared an emergency using that specific word, "emergency." The first officer misunderstood the difference between "priority" and "emergency," English was not his first language. The captain wasn't paying close enough attention to communications between the first officer and ATC and accepted the first officer's assurances that an emergency had been declared.

So where does that leave us, as pilots? Flow control in this country is much better and air traffic controllers do seem to be in better tune with even the hint of an emergency status of their aircraft. But as pilots we can learn to communicate better too. See Declaring an Emergency for more about this.

1

Accident report

- Date: 25 January 1990

- Time: 21:34 EST

- Type: Boeing 707-321B

- Operator: Avianca

- Registration: HK-2016

- Fatalities: 8 of 9 crew, 65 of 149 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airport: (Departure) Rionegro/Medellin-Jose Cordova Airport (MDE/SKRG)

- Airport: (Destination) New York-John F. Kennedy International Airport, NY (JFK/KJFK), United States of America

2

Narrative

- AVA052 entered the airspace of Miami Air Route Traffic Control Center (ARTCC) at approximately 1728 at FL 350. [ . . . ] As the flight proceeded northward, it was placed in holding three times by ATC. AVA052 was instructed to enter holding first over ORF. This period of holding was from 1904 to 1923 (19 minutes). The flight was placed in holding a second time at BOTON intersection, near Atlantic City, New Jersey. This period of holding was from 1943 to 2012 (29 minutes). The flight was placed in holding a third time at CAMRN intersection. CAMRN intersection is 39 nautical miles south of JFK. This third period of holding was from 2018 to 2047 (29 minutes).

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.1

Not many airplanes have an hour an 17 minutes of holding fuel to spare.

- Between the ORF and CAMRN intersections, AVA052 was cleared to descend to several lower altitudes. The flight entered the holding pattern at CAMRN, at 14,000 feet mean sea level (msl). The flight was subsequently descended to 11,000 feet while in the holding pattern. Figure 1 depicts the track of AVA052 beginning at 2042:59.

- At 2044:43, while holding at CAMRN, the New York (NY) ARTCC radar controller advised AVA052 to expect further clearance (EFC) at 2105. The flight had previously been issued EFC times of 2030 and 2039. The first officer responded, "...ah well I think we need priority we're passing [unintelligible]."

- The radar controller inquired, "...roger how long can you hold and what is your alternate?" [The] first officer responded, "Yes sir ah we'll be able to hold about five minutes that's all we can do. "The controller replied, "...roger what is your alternate?" The first officer responded, "ah we said Boston but ah it is ah full of traffic I think." The controller said, "...say again your alternate airport?" The first officer responded, "it was Boston but we can't do it now we, we, don't, we run out of fuel now."

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.1

That should have been a signal to both the controller and the pilots; they had exhausted their alternate fuel in the holding patterns and now were proceeding to their destination without a viable alternate.

- At 2046:27, the handoff controller advised the NY TRACON controller, "Avianca zero five two just coming on CAMRN can only do 5 more minutes in the hold think you'll be able to take him or I'll set him up for his alternate." [ . . . the ] NY TRACON controller said, "slow him to one eight zero knots and I'll take him he's radar three southwest of CAMRN." The handoff controller replied, "one eighty on the speed, radar contact and I'll put him on a forty [040 degree] heading." The New York TRACON controller responded, "that's good."

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.1

While this was a step in the right direction, the sense of urgency was not transmitted to NY ARTCC.

- After being advised by the handoff controller that the NY TRACON would be able to accept AVA052, the NY ARTCC radar controller relayed, "Avianca zero five two heavy cleared to the Kennedy Airport via heading zero four zero maintain one one thousand speed one eight zero." After the first officer acknowledged the clearance, AVA052 was instructed to contact the NY TRACON. Recorded air traffic control radar data indicates that AVA052 departed the holding pattern at CAMRN intersection at 2047:OO.

- At 2047:21, the first officer contacted the NY TRACON feeder controller, " . ..we have ATIS information YANKEE with you one one thousand." [The] feeder controller replied, "Avianca zero five two heavy New York approach thank you reduce speed to one eight zero if you're not already doing it you can expect an ILS two two left altimeter two niner six niner proceed direct Deer Park."

- At 2056:16, the feeder controller advised, "Avianca zero five two I have a windshear for you ah at fifteen ah increase of ten knots at fifteen hundred feet and then an increase of ten knots at five hundred feet reported by seven twenty seven." At 2056:25, the first officer acknowledged receipt of the windshear advisory.

- At 2103:46, the flightcrew began to discuss the procedure for go-around, with 1,000 pounds or less of fuel in any tank. [The] second officer stated, in Spanish, "then the go-around procedure is stating that the power be applied slowly and to avoid rapid accelerations and to have a minimum of nose up attitude."

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.1

Their airline did not have a specified number for what constitutes minimum fuel. Their aircraft flight manual used 1,000 pounds or less in any main tank or 7,000 pounds or less total.

- At 2111:07, the final controller stated, "...you are one five miles from the outer marker maintain two thousand until established on the localizer cleared ILS two two left."

- At 2121:41, the captain said, "localizer glideslope one thousand feet stand by for lights." At 2121:59, the first officer said, "slightly below glideslope." At 2122:05, AVA052 was about 3.2 miles from the approach end of runway 22L. At 2122:07, the first officer said, "one thousand feet above field."

- At 2122:57, the first officer said, "this is the windshear." At 2123:08, the second officer said, "glideslope." At 2123:08, the first officer said, "glideslope;" at 2123:09, "sink rate; and at 2123:10, "five hundred feet."

- Between 2123:08 and 2123:23, there were 11 "whoop pull up" voice alerts from the airplane's ground proximity warning system (GPWS). Between 2123:25 and 2123:29, there were four "glideslope" deviation alerts from the GPWS. At 2123:23, the captain asked "the runway where is it?" At this time, AVA052 was 1.3 miles from the approach end of runway 22 left at an altitude of 200 feet. At 2123:27 (CVR), the first officer said, “I don't see it I don't see it." At 2123:28, the captain said, "give me the landing gear up landing gear up."

- At 2124:00 (CVR), the captain said, “I don't know what happened with the runway I didn't see it." Also, the second officer said, “‘I didn't see it," and the first officer said, “I didn't see it."

- At 2124:04, JFK tower controller stated, "Avianca zero five two you're making the left turn correct sir." At 2124:06, the captain said, "tell them we are in emergency." The second officer said, (CVR), "two thousand feet." [The] first officer replied to JFK tower, "that's right to one eight zero on the heading and ah we'll try once again we're running out of fuel." At 2124:15, JFK tower stated, "okay." At 2124:22 (CVR), the captain said, "advise him we are emergency." [The] captain said, "did you tell him." The first officer replied, 'yes sir, I already advised him."

- At 2125:08, the captain said, "advise him we don't have fuel." [The] first officer made the radio call, "Climb and maintain three thousand and ah we're running out of fuel sir." At 2125:28, the captain said, "did you already advise that we don't have fuel." The first officer replied, "Yes sir. I already advise him hundred and eighty on the heading we are going to maintain three thousand feet and he's going to get us back." The captain replied, "okay."

- At 2129:11, the first officer asked, "Ah can you give us a final now...?" The NY TRACON final controller responded, "...affirmative sir turn left heading zero four zero." At 2130:32, the final controller stated, "Avianca fifty two climb and maintain three thousand." At 2130:36, the first officer replied, "ah negative sir we just running out of fuel we okay three thousand now okay." The controller responded, "Okay turn left heading three one zero sir."

- At 2132:14, the first officer said, "three three zero the heading." At 2132:39, the second officer said, "flame out flame out on engine number four." At 2132:42, the captain said, "flame out on it." The second officer then said, "flame out on engine number three essential on number two or number one." At 2132:49, the captain said, "show me the runway."

- At 2132:49 the first officer radioed, "...we just ah lost two engines and ah we need priority please." The final controller then instructed AVA052 to turn to a heading of two five zero degrees, advised the flight that it was fifteen miles from the outer marker and cleared for the ILS approach to runway 22 left.

- At 2133:07, the final controller informed the flight, "...you're one five miles from outer marker maintain two thousand until established on the localizer cleared for ILS two two left."

- At 2133:23, the first officer replied, "it is ready on two." This radio transmission was the last clearance acknowledged by AVA052.

- At 2134:00, the NY TRACON final controller asked AVA052, "You have ah you have enough fuel to make it to the airport?" There was no response from the airplane.

- At about this time, AVA052 impacted on a hillside in a wooded residential area on the north shore of Long Island. The starboard side of the forward fuselage impacted and fractured the wooden deck of a residential home. There was no fire.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.1

- As of January 25, 1990, the captain had accrued a total flight time of 16,787 hours, 1,534 of which were in the B-707. The captain was also a pilot in the Colombian Air Force Reserve and a member of the Colombian Air Line Pilots Association. He had no record of previous accidents.

- The first officer/copilot [ . . . ] possessed a U.S. FAA commercial pilot's license, with a latest date of issuance of April 7, 1983. He possessed FAA license ratings of "airplane, single and multiengine land, and instrument, airplane." During October 1989, the first officer transitioned from the B-727 to the B-707. The transition period included 14 hours of simulated flight and 135 hours of ground instruction. The airline states that, in accordance with the requirements of the Colombian Civil Aviation Administration (Departamento Administrativo de Aeronautical Civil - DAAC), the first officer flew 30 hours as an observer in the jump seat of the B-707. The first officer's initial line check in a B-707 was on a flight from Bogota to JFK in December 1989, the month prior to the accident.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.5

- The B-707 uses a capacitance-type fuel quantity gauging system. The system's components include fuel indicators and tank probes. The fuel quantity indicator is a sealed, self-balancing, motor-driven instrument containing a motor, pointer assembly, amplifier, bridge, circuit, and adjustment potentiometer. A change in the fuel quantity of a tank causes a change in the capacitance of the tank probe. The tank probe is one arm of a capacitance bridge circuit. The voltage signal resulting from the unbalanced bridge is amplified by a phase winding of a two-phase induction motor in the indicator. The induction motor drives the wiper or a rebalancing potentiometer in the proper direction to balance the bridge and, at the same time, positions an indicator pointer to show the quantity of fuel remaining in the tank.

- Fuel is contained in seven tanks located within the wing and wing center section. The reserve tanks and tanks No. 1, No. 2, No. 3, and No. 4 are integral to the wing structure. The center tank consists of seven removable bladder cells within the wing center section, interconnected to two integral wing root section tanks.

- Fuel quantity indicators display usable fuel only. Maximum error for each indicator is ± 3 percent of full-scale reading. The quantity indicators should read zero when all usable fuel has been consumed.

- On August 1, 1980, the Boeing Company published a revised version of Bulletin No. 80-l. The revision contained much of the original language but also stated the following:

Minimum fuel for landing can best be determined by each operator due to differences in weather conditions, air traffic control delays, airline policy, etc. However, operators should consider the possible fuel quantity indicator error shown... (plus or minus 3 percent of tank full scale reading) when determining the minimum indicated fuel for landing. For example, if the actual total of fuel in the four main tanks for landing is 4,000 lbs. (1,814 kgs.) the total indicated fuel could be as low as 1,300 lbs. (590 kgs.) or as high as 6,700 lbs. (3,039 kgs.). If any delay is anticipated due to extended radar vectoring, etc., or if a go-around is likely, then additional fuel for these contingencies should be added to the planned fuel quantity for landing. During an operation with very low fuel quantity, priority handling from ATC should be requested.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.6

In other words, with the four main tanks reading 1,000 lbs. each, you could have as little as 400 lbs. in any of the tanks.

- FAA order 7110.65F, "Air Traffic Control," Chapter 9, provides guidelines to air traffic controllers on assisting aircraft in an emergency. An emergency can be either a "distress" or an "urgency" condition, as defined in the "Pilot/Controller Glossary." A pilot who encounters a distress condition would declare an emergency by beginning the initial communication with the word "MAYDAY," preferably repeated three times. For an urgency condition, the word "PAN-PAN" should be used in the same manner.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.17

FAA Order 7110.65 is up to version "V" now and there is a significant change since version "F" that says:

If the words “Mayday” or “Pan-Pan” are not used and you are in doubt that a situation constitutes an emergency or potential emergency, handle it as though it were an emergency.

- After the controller has determined the extent of the emergency, he is required to obtain enough information to handle the emergency intelligently. The controller is required to base his decisions regarding the type of assistance on the pilot's determination because the pilot is authorized by FAR 91 to determine a course of action. When an emergency has been declared by a pilot, or when an air traffic controller has determined that an emergency exists, the controller is required to provide maximum assistance. The controller is expected to select and pursue a course of action that appears to be most appropriate under the circumstances and that most nearly conforms to the instructions in the ATC Handbook. responsibility of the controller to forward to pertinent facilities and agencies any information concerning the emergency aircraft.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶1.17

3

Analysis

- The evidence confirmed that this accident occurred when the airplane's engines lost power from fuel exhaustion while the flight was maneuvering for a second instrument approach to JFK. Significant evidence was information contained on the CVR and examination of the airplane's wreckage. There was an absence of fuel odor at the accident site, and no fire erupted during the impact. The only fuel found in the airplane was residual unusable fuel. There was no rotational damage to any of the four engines from impact forces, indicating that they had ceased operation before ground impact. In addition, the investigation found no engine or fuel system componentmal functions, including any that could have caused a premature exhaustion of fuel or a loss of fuel supply to the engine.

- One possibility for the flightcrew's delay in expressing its concerns may have been a misconception of the significance of the EFC's issued by ATC. The first EFC was for 2030, issued about 8 minutes before the flight entered holding at CAMRN, and the second EFC was for 2039 as the flight entered holding at CAMRN. The flightcrew may have assumed that the previous EFC's were valid times for which they would receive clearance to depart holding and begin the approach to JFK before the fuel state became more critical. In fact, EFC's are merely estimates by the controllers based on a dynamic traffic and weather situation and are issued to provide a time to commence the approach should the flight lose radio contact. When ATC issued a third EFC of 2105, the flightcrew apparently finally realized that they had to commence an approach and therefore requested priority handling.

- However, the Safety Board concludes that the flightcrew had already exhausted its reserve fuel to reach its alternate by the time it asked for priority handling. When asked a second time for its alternate, the first officer responded, at 2046:24, "It was Boston, but we can't do it now, we, we, don't, we run out of fuel now." Although the first officer had radioed at 2046:03, "Yes sir, ah, we'll be able to hold about five minutes, that's all we can do," the airplane did not have sufficient fuel to fly to its alternate.

- Moreover, AVA052's fuel state at the time it was cleared from holding at CAMRN to commence its approach to JFK was already critical for its destination. To help ensure sufficient fuel to complete a safe landing, an emergency should have been declared in order to receive expedited handling. The airplane exhausted its fuel supply and crashed 47 minutes after the flightcrew stated that there was not sufficient fuel to make it to the alternate. This occurred after the flight was vectored for an ILS approach to the destination, missed the first approach, and was unable to complete a second approach.

- The airline's only written procedure for minimum fuel operation was published in its B-707 Operations Manual. The procedure was based upon an indicated fuel quantity in any main tank of 1,000 pounds or less. The procedure did not address a minimum fuel quantity for which a flight should be at the outer marker, inbound to the runway.

- The Boeing Company, on February 15, 1980, as a result of some low fuel operations and incidents, issued Operations Manual Bulletin 80-l to all B-707 operators. The bulletin provided information regarding flight operations with low fuel indications. Boeing recommended that 7,000 pounds be used as the minimum indicated amount of fuel for landing. Boeing assumed the worst case main tank fuel quantity indicating error of 2,700 pounds, and a minimum of 1,000 pounds in each of the airplane's four main fuel tanks.

- Because the CVR retained only 40 minutes of intracockpit conversations, the Safety Board could not determine whether the crew discussed, prior to their departure from CAMRN, the minimum fuel level that they should have onboard when commencing the approach. However, it is apparent from air-to-ground transmissions while holding at CAMRN (first, the expressed need for "priority" at about 2045 and second, the observations that they could hold only 5 minutes and that they could not reach Boston only minutes later) that the crew were aware of and concerned about the fuel problem. Whether the captain, or first officer, or both, believed that these transmissions to ATC conveyed the urgency for emergency handling is unknown. However, at 2054:40, when AVA052 was given a 360 turn for sequencing and spacing with other arrival traffic, the flightcrew should have known that they were being treated routinely and that this situation should have prompted them to question the clearance and reiterate the criticality of their fuel condition. At that time, they could have declared an emergency, or at least requested direct routing to the final approach in order to arrive with an acceptable approach minimum fuel level.

- These intracockpit conversations indicate a total breakdown in communications by the flightcrew in its attempts to relay the situation to ATC. The accident may have been inevitable at that point, because the engines began to flame out only about 7 minutes later. However, it is obvious that the first officer failed to convey the message that the captain intended.

- All clearances issued were in compliance with ATC directives; however, it is possible that the flightcrew was misled by the clearances. That is, they may have interpreted the EFC's as actual times that they would be cleared to continue to the destination without further delay and they elected to use the reserve fuel necessary to reach the alternate airport.

- None of the controllers involved in the handling of AVA052 considered the request for "priority," or the comments about running out of fuel, to be significant or an emergency request by AVA052.

- In public hearing testimony, one foreign airline captain referred to non-U.S. airline pilots with "200-word vocabularies" flying into the United States. He may have been exaggerating for emphasis, but his point is well taken. If a pilot, or flightcrew, has a limited English language vocabulary, he has to rely heavily on the meaning of the words he does know. If those words have a vague meaning, such as the word "priority," or if a clear set of terms and words are not used by pilots and controllers, confusion can occur as it did in this accident.

- The word "priority" was used in procedures' manuals provided by the Boeing Company to the airlines. A captain from Avianca Airlines testified that the use by the first officer of the word "priority," rather than "emergency," may have resulted from training at Boeing. The captain also testified that airline personnel, who provided flight and ground instruction to the first officer of AVA052, were trained by Boeing. He stated that these personnel received the impression from the training that the words priority and emergency conveyed the same meaning to air traffic control. Boeing Bulletins 80-l and 80-l (Revised), addressing operations with low fuel quantity indications, state that, "during any operation with very low fuel quantity, priority handling from ATC should be requested."

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶2

4

Cause

- The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the failure of the flightcrew to adequately manage the airplane's fuel load, and their failure to communicate an emergency fuel situation to air traffic control before fuel exhaustion occurred. Contributing to the accident was the flightcrew's failure to use an airline operational control dispatch system to assist them during the international flight into a high-density airport in poor weather. Also contributing to the accident was inadequate traffic flow management by the FAA and the lack of standardized understandable terminology for pilots and controllers for minimum and emergency fuel states.

- The Safety Board also determines that windshear, crew fatigue and stress were factors that led to the unsuccessful completion of the first approach and thus contributed to the accident.

Source: NTSB AAR-91/04, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-91/04, Avianca, The Airline of Columbia, Boeing 707-321B, HK-2016, Fuel Exhaustion, Cove Neck, New York, January 25, 1990