Updated:

2013-07-18

"Controlled Flight Into Terrain" is just the end result of this mishap. The circumstances that led to the CFIT serve as lessons to all pilots on multiple issues:

- Instrument Procedures — The captain briefed the glide slope was out of service and yet throughout the approach kept asking if it was indeed out and then rationalizing that is was okay. He stated at one point "no flags" so what he could have been seeing is a "false glide slope" or, as happened to a GIII could have misread another pointer as the glide slope. The flight data recorder shows that they flew a fairly constant rate of descent into a point several miles short of the runway.

- Equipment Out-of-Service — Though the NTSB ruled out the possibility of a false glide slope guiding the airplane into the ground a lesson is clear. The pilot thought he saw the glide slope flag clear and then decided to fly the indication. He may have seen the flag flicker and then fixated on another needle. In any case, he knew the glide slope was called out of service and should have stuck to glide slope out procedures.

- Situational Awareness — The crew impacted the ground at 660' MSL, 3.3 nm from the runway which was at 238' MSL. Using basic 60 to 1 they should have been at 990' above the runway elevation, or 1228' MSL. Even without these math skills, the pilots should have realized they were too low given their distance from the runway. The NTSB found that Korean Air pilots were not trained that the DME isn't always coincident with the runway end; at this airport they were three miles apart. I find that hard to believe, the captain had decades of experience flying around the world and indeed had flown into this airport six times previous. But it could explain why they didn't think it unusual to be so low at this point on approach.

- Stabilized Approach — After their GPWS alerted them to a high sink rate of 1,400 feet per minute, the copilot said "Sink rate okay." While the concept of Stabilized Approach maximum deviation parameters may not have existed back then, pilots should have an instinctive understanding of how much sink rate is okay. (A 747's sink rate should be around 700 feet per minute at most weights.)

- Crew Resource Management —Five seconds prior to impact the first officer said, let's make a missed approach." The captain didn't react until four seconds later when the flight engineer said, "go around." There are a few things in the cockpit that aren't done slowly and smoothly and one of those is the execution of a go around. Good Crew Resource Management also dictates that the go around call be made assertively.

1

Accident report

- Date: 6 AUG 1997

- Time: 01:42

- Type: Boeing 747-3B5

- Operator: Korean Air

- Registration: HL7468

- Fatalities: 22 of 23 crew, 228 of 254 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airports: (Departure) Seoul-Gimpo International Airport (SEL/RKSS), South Korea, (Arrival) Guam Won Pat International Airport (GUM/PGUM), Guam

2

Narrative

According to Korean Air company records, the flight crew arrived at the dispatch center in the Korean Air headquarters building in Seoul about 2 hours before the scheduled departure time of 2105 (2005 Seoul local time) on August 5, 1997. The original flight plan for flight 801 listed a different captain’s name. The captain aboard the accident flight had initially been scheduled to fly to Dubai, United Arab Emirates; however, because the accident captain did not have adequate rest for that trip, he was reassigned the shorter trip to Guam.

According to the cockpit voice recorder (CVR), the captain was performing the pilot flying (PF) duties, and the first officer was performing the pilot-not-flying (PNF) duties.

About 0113:33, the CVR recorded the captain saying, “we better start descent;” shortly thereafter, the first officer advised the controller that flight 801 was “leaving four one zero for two thousand six hundred.” The controller acknowledged the transmission.

The CVR recorded the captain making several remarks related to crew scheduling and rest issues. About 0120:01, the captain stated, “if this round trip is more than a nine hour trip, we might get a little something…with eight hours, we get nothing . . . eight hours

About 0120:28, the captain further stated, “probably this way [unintelligible words], hotel expenses will be saved for cabin crews, and maximize the flight hours. Anyway, they make us [747] classic guys work to maximum.” About 0121:13, the captain stated, “eh . . . really . . . sleepy.”

Source: NTSB Report, ¶1.1

The captain spoke more than a few times during the descent about crew rest issues.

About 0121:59, the first officer stated, “captain, Guam condition is no good.” About 0122:06, the CERAP controller informed the flight crew that the automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information Uniform was current and that the altimeter setting was 29.86 inches of mercury (Hg). About 0122:11, the first officer responded, “Korean eight zero one is checked uniform;” his response did not acknowledge the altimeter setting.

About 0138:49, the CERAP controller instructed flight 801 to “. . . turn left heading zero nine zero join localizer;” the first officer acknowledged this transmission. At that time, flight 801 was descending through 2,800 feet msl with the flaps extended 10° and the landing gear up. About 0139:30, the first officer said, “glideslope [several unintelligible words]...localizer capture [several unintelligible words]...glideslope...did.” About 0139:44, the controller stated, “Korean Air eight zero one cleared for ILS runway six left approach . . . glideslope unusable.” The first officer responded, “Korean eight zero one roger . . . cleared ILS runway six left;” his response did not acknowledge that the glideslope was unusable.

According to the CVR, about 0139:55 the flight engineer asked, “is the glideslope working? glideslope? yeh?” One second later, the captain responded, “yes, yes, it’s working.” About 0139:58, an unidentified voice in the cockpit stated, “check the glideslope if working?” This statement was followed 1 second later by an unidentified voice in the cockpit asking, “why is it working?” About 0140:00, the first officer responded, “not useable.”

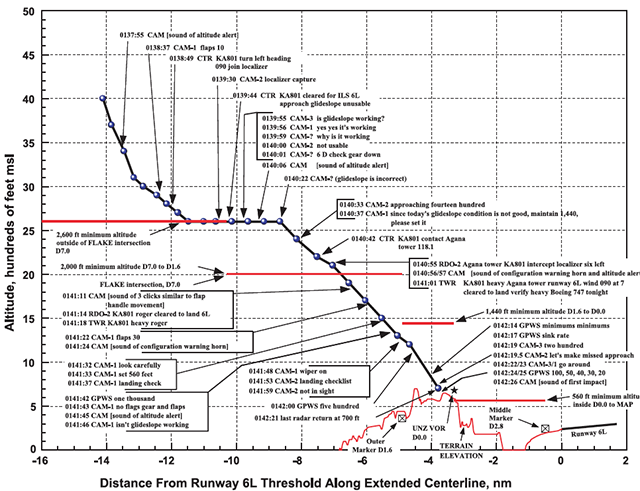

About 0140:06, the CVR recorded the sound of the altitude alert system chime. According to information from the flight data recorder (FDR), the airplane began to descend about 0140:13 from an altitude of 2,640 feet msl at a point approximately 9 nm from the runway 6L threshold (5.7 nm from the NIMITZ VOR). About 0140:22, an unidentified voice in the cockpit said, “glideslope is incorrect.” About 0140:33, as the airplane was descending through 2,400 feet msl, the first officer stated, “approaching fourteen hundred [feet].” About 4 seconds later, when the airplane was about 8 nm from the runway 6L threshold, the captain stated, “since today’s glideslope condition is not good, we need to maintain one thousand four hundred forty [feet]. please set it.” An unidentified voice in the cockpit then responded, “yes.” About 0140:42, the CERAP controller instructed flight 801 to contact the Agana control tower; the first officer acknowledged the frequency change. The first officer contacted the Agana tower about 0140:55 and stated, “Korean air eight zero one intercept the localizer six left.” Shortly after this transmission, the CVR again recorded the sound of the altitude alert chime, and the FDR data indicated that the airplane was descending below 2,000 feet msl at a point 6.8 nm from the runway threshold (3.5 nm from the VOR).

About 0141:01, the Agana tower controller cleared flight 801 to land. About 0141:14, as the airplane was descending through 1,800 feet msl, the first officer acknowledged the landing clearance, and the captain requested 30° of flaps. No further communications were recorded between flight 801 and the Agana control tower.

About 0141:31, the first officer called for the landing checklist. About 0141:33, the captain said, “look carefully” and “set five hundred sixty feet” (the published MDA). The first officer replied “set,” the captain called for the landing checklist, and the flight engineer began reading the landing checklist. About 0141:42, as the airplane descended through 1,400 feet msl, the CVR recorded the sound of the ground proximity warning system (GPWS)19 radio altitude callout “one thousand [feet].” One second later, the captain stated, “no flags gear and flaps,” to which the flight engineer responded, “no flags gear and flaps.” About 0141:46, the captain asked, “isn’t glideslope working?” There was no indication on the CVR that the first officer and flight engineer responded to the this question. About 0141:48, the captain stated, “wiper on.” About 0141:53, the CVR recorded the sound of the windshield wipers starting. The windshield wipers remained on throughout the remainder of the flight.

About 0141:53, the first officer again called for the landing checklist, and the flight engineer resumed reading the checklist items. About 0141:59, when the airplane was descending through 1,100 feet msl at a point about 4.6 nm from the runway 6L threshold (approximately 1.3 nm from the VOR), the first officer stated “not in sight?” One second later, the CVR recorded the GPWS radio altitude callout of “five hundred [feet].” According to the CVR, about 2 seconds later the flight engineer stated “eh?” in an astonished tone of voice

About 0142:05, the captain and flight engineer continued the landing checklist. About 0142:14, as the airplane was descending through 840 feet msl and the flight crew was performing the landing checklist, the GPWS issued a “minimums minimums” annunciation followed by a “sink rate” alert about 3 seconds later. The first officer responded, “sink rate okay” about 0142:18; FDR data indicated that the airplane was descending 1,400 feet per minute at that time.

About 0142:19, as the airplane descended through 730 feet msl, the flight engineer stated, “two hundred [feet],” and the first officer said, “let’s make a missed approach.” About 1 second later, the flight engineer stated, “not in sight,” and the first officer said, “not in sight, missed approach.” About 0142:22, as the airplane descended through approximately 680 feet msl, the FDR showed that the control column position began increasing (nose up) at a rate of about 1° per second, and the CVR indicated that the flight engineer stated, “go around.” When the captain stated “go around” about 1 second later, the airplane’s engine pressure ratios and airspeed began to increase. However, the rate of nose-up control column deflection remained about 1° per second. At 0142:23.77, as the airplane descended through 670 feet msl, the CVR recorded the sound of the autopilot disconnect warning. At 0142:24.05, the CVR began recording sequential GPWS radio altitude callouts of “one hundred . . . fifty . . . forty . . . thirty . . . twenty [feet].” About 0142:26, the airplane impacted hilly terrain at Nimitz Hill, Guam, about 660 feet msl and about 3.3 nm from the runway 6L threshold. FDR data indicated that, at the time of initial ground impact, the pitch attitude of the airplane was increasing through 3°. The accident occurred at 13° 27.35 minutes north latitude and 144° 43.92 minutes east longitude during the hours of darkness. The CVR stopped recording about 0142:32.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶1.1

"Let's make a missed approach" certainly isn't very assertive. If it seemed the crew was reluctant to direct the captain to go around, that is a trend seen often in airlines of Korea.

3

Analysis

The Crew

The captain, age 42, was hired by Korean Air on November 2, 1987. He was previously a pilot in the Republic of Korea Air Force. He held an Airline Transport Pilot (ATP) certificate issued by the Korean Ministry of Construction and Transport (MOCT) on April 19, 1992, with type ratings in the Boeing 727 and 747. The captain qualified as a 727 first officer on December 19, 1988, and as a 747 first officer on February 13, 1991. He upgraded to 727 captain on December 27, 1992, and 747 captain on August 20, 1995.

The first officer, age 40, was hired by Korean Air on January 10, 1994. He was previously a pilot in the Republic of Korea Air Force. He held an ATP certificate issued by the FAA on July 10, 1994, and a Korean ATP certificate issued by the MOCT on March 28, 1997. He received a 747 type rating on March 11, 1995, and qualified as a 747 first officer on July 23, 1995.

The flight engineer, age 57, was hired by Korean Air on May 7, 1979. He was previously a navigator in the Republic of Korea Air Force. He obtained his flight engineer’s certificate on December 29, 1979, and was qualified on the Boeing 727 and 747 and Airbus A300 airplanes.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶1.5

This was fairly typical for Korean Air to have former Republic of Korea Air Force pilots in the cockpit. Listening to the cockpit voice recorder of this and other Airlines of Korea accidents, you detect a definite command hierarchy reminiscent of pre-CRM cockpits in the rest of the world. The crew rarely challenged the captain's authority.

The Approach

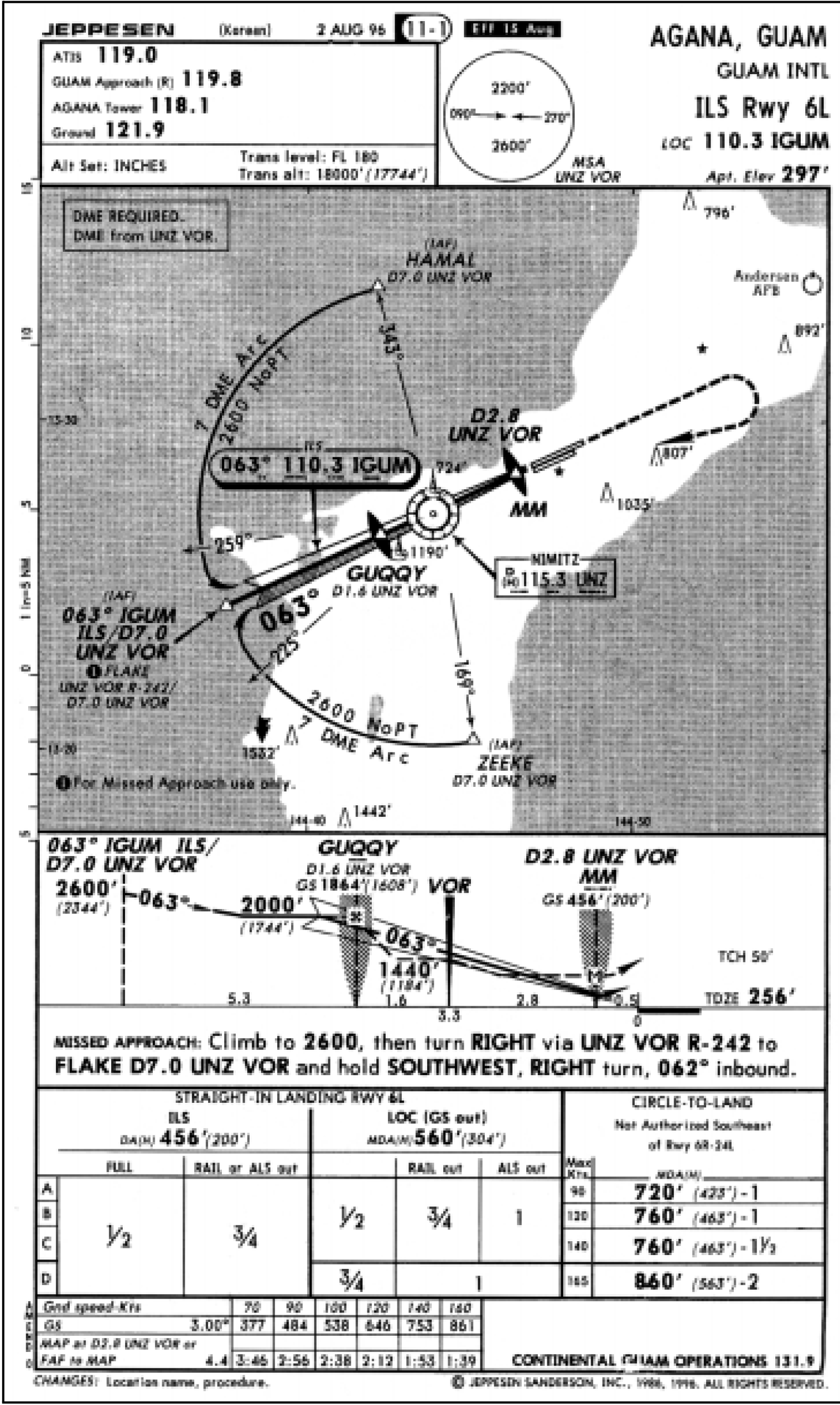

Instrument approaches available for runway 6L at the time of the accident were the ILS (localizer only, glideslope out of service), the VOR/DME, and the VOR.

The execution of the Guam ILS runway 6L localizer-only (glideslope out) approach requires the use of the NIMITZ VOR as a step-down fix between the final approach fix (FAF) and the runway and DME to identify the step-down points. The DME is not colocated or frequency paired with the localizer transmitter (which is physically located at the airport); rather, it is colocated and frequency paired with the NIMITZ VOR.

The nonprecision localizer-only approach requires the use of the localizer to obtain lateral guidance to the runway, the DME to identify the step-down points, and the VOR to identify the final step-down fix to the MDA.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶1.10.3

CVR information indicated that the captain was flying the airplane on autopilot during the approach. As flight 801 descended on the approach, the captain twice commanded the entry of lower altitudes into the airplane’s altitude selector before the airplane had reached the associated step-down fix. After the captain heard the first officer callout “approaching fourteen hundred [feet]” about 0140:33, as the airplane was passing 5 DME at 2,400 feet msl, the captain directed the first officer to reset the altitude selector to 1,440 feet, replacing the step-down altitude of 2,000 feet before the autopilot had captured that altitude or reached the GUQQY outer marker/1.6 DME fix. Further, about 0141:33, with the flight neither having leveled off at 1,440 feet msl nor reached the UNZ VOR step-down fix, the captain instructed the first officer to set 560 feet, the MDA, in the altitude selector.

The altitude selector provides the basis for the altitude alert’s aural annunciations and the autopilot’s altitude capture functions. The captain’s premature orders to reset the altitude selector indicated that he had lost awareness of the airplane’s position along the final approach course. Therefore, as a result of the captain’s commanded input to the altitude selector, the autopilot continued to descend the airplane prematurely through the 2,000- and 1,440-foot intermediate altitude constraints of the approach procedure. The CVR comments indicated no awareness by the captain that the airplane was descending prematurely below the required intermediate altitudes.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶2.3

This can be surprising the first time you see it, provided you see it. Without an intelligent Vertical Navigation system, you must allow the autopilot to capture a new altitude before you give it the next altitude.

CVR information indicated that the captain briefed a visual approach in his approach briefing, which he referred to as a “short briefing.” However, the captain also briefed some elements of the localizer-only instrument approach, indicating that he intended to follow that approach as a supplement or backup to the visual approach. Specifically, the captain’s briefing included a reminder that the glideslope was inoperative, some details of the radio setup, the localizer-only MDA, the missed approach procedure, and the visibility at Guam (stated by the captain to be 6 miles). However, the captain did not brief other information about the localizer-only approach, including the definitions of the FAF and step-down fixes and their associated crossing altitude restrictions or the title, issue, and effective dates of the approach charts to be used. The Safety Board notes that the landing briefing checklist did not specifically require the captain to brief the fix definitions, crossing altitudes, or approach chart title and dates, although it would have been good practice to do so.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶2.4.1

We often brief a visual approach with an instrument approach back up, and then we provide an abbreviated instrument approach briefing or not instrument approach briefing at all. When you are forced to go to the instrument approach, you are tempted to say the briefing is done. A better technique is to fully brief the instrument approach, even if it is a back up.

As the approach progressed without encountering the visual conditions the captain had anticipated, the captain likely experienced increased stress because of his inadequate preparation for the nonprecision approach, which made the approach increasingly challenging. CVR and FDR data indicated that, shortly after the captain appeared to become preoccupied with the status of the glideslope, he allowed the airplane to descend prematurely below the required intermediate altitudes of the approach. Thus, the captain may have failed to track the airplane’s position on the approach because he believed that he would regain visual conditions, the airplane was receiving a valid glideslope signal, and/or the airplane was closer to the airport than its actual position.

Regardless of the reason for failing to track the airplane’s position, the captain conducted the approach without properly cross-referencing the positional fixes defined by the VOR and DME with the airplane’s altitude. Therefore, the Safety Board concludes that, as a result of his confusion and preoccupation with the status of the glideslope, failure to properly cross-check the airplane’s position and altitude with the information on the approach chart, and continuing expectation of a visual approach, the captain lost awareness of flight 801’s position on the ILS localizer-only approach to runway 6L at Guam International Airport and improperly descended below the intermediate approach altitudes of 2,000 and 1,440 feet, which was causal to the accident.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶2.4.1.4

I've noticed a trend with many accidents of the Airlines of Korea: their pilots seem to rely on an ILS glide slope so heavily that they fear a visual approach.

Crew Resource Management

CVR evidence indicated that the flight crew seemed confused about, and did not react to, a series of audible ground proximity warning system (GPWS) alerts during the final approach. The first audible GPWS callout occurred about 0141:42, with the “one thousand [feet]” altitude call. A second GPWS callout of “five hundred [feet]” occurred about 0142:00 (when the airplane was descending through about 1,200 feet msl), to which the flight engineer responded in astonishment, “eh?” However, FDR data indicated that no change in the airplane’s descent profile followed, and the CVR indicated that the flight engineer continued to complete the landing checklist. Similarly, no flight crew discussion followed the GPWS callout of “minimums” about 0142:14, and the first officer dismissed a GPWS “sink rate” alert 3 seconds later by stating “sink rate okay.” About 0142:19, the flight engineer called “two hundred [feet],” followed immediately by the first officer saying “let’s make a missed approach.” The flight engineer immediately responded “not in sight,” followed by the first officer repeating “not in sight missed approach.” According to the CVR, a rapid succession of GPWS altitude callouts down to 20 feet followed, as the flight crew attempted to execute the missed approach.

Although the first officer properly called for a missed approach 6 seconds before impact, he failed to challenge the errors made by the captain (as required by Korean Air procedures) earlier in the approach, when the captain would have had more time to respond. Significantly, the first officer did not challenge the captain’s premature descents below 2,000 and 1,440 feet.

The Safety Board was unable to identify whether the absence of challenges earlier in the approach stemmed from the first officer’s and the flight engineer’s inadequate preparation during the approach briefing to actively monitor the captain’s performance on the localizer approach, their failure to identify the errors made by the captain (including the possibility that they shared the same misconceptions as the captain about the glideslope status/FD mode or the airplane’s proximity to the airport), and/or their unwillingness to confront the captain about errors that they did perceive.

Problems associated with subordinate officers challenging a captain are well known. For example, in its study of flight crew-involved major air carrier accidents in the United States, the Safety Board found that more than 80 percent of the accidents studied occurred when the captain was the flying pilot and the first officer was the nonflying pilot (responsible for monitoring). Only 20 percent of the accidents occurred when the first officer was flying and the captain was monitoring. This finding is consistent with testimony at the Safety Board’s public hearing, indicating that CFIT accidents are more likely to occur (on a worldwide basis) when the captain is the flying pilot.

The Safety Board is concerned that the use of the nonflying pilot in a passive role, while the flying pilot is responsible for the approach procedure, programming the autopilot/FD controls, and monitoring the aircraft flightpath, places an inordinately high work load on the flying pilot and under-tasks the nonflying pilot. The Board is also concerned that, when the nonflying pilot has a passive role in the approach, the flying pilot may erroneously consider the lack of input from the nonflying pilot as confirmation that approach procedures are being properly performed.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶2.4.2

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the captain’s failure to adequately brief and execute the nonprecision approach and the first officer’s and flight engineer’s failure to effectively monitor and cross-check the captain’s execution of the approach. Contributing to these failures were the captain’s fatigue and Korean Air’s inadequate flight crew training.

Source: NTSB Report, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-00/01, Korean Air Flight 801, Boeing 747-300, HL7468, Controlled Flight Into Terrain, Nimitz Hill, Guam, August 6, 1997