Taken in isolation, this accident appears to be a simple case of a pilot giving into spatial disorientation while turning after takeoff into the black sky, over an equally black ocean. Many pilots have succumbed to the same fate. But in this case, they were flying a jet airliner designed for this kind of thing with back up instruments and two other pilots in the cockpit to ensure at least one pilot knew which way was up. There were also complicating factors. But there is reason to believe captains for this airline were allowed to let their skill atrophy and cockpit non-captains were expected to keep quiet about this kind of thing.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-02-01

This was another incident in a series of 13, 11 of which pointed to a problem with the Crew Resource Management Culture at Pan American World Airways at the time. They were able to reverse this culture and became one of the safest airlines in the world.

There isn't much out there on this crash. I have the French report but don't have a translation. A reader who is fluent in French and lived in Tahiti at the time offers his take from the report. I think we can draw enough from the circumstances to add this to a long case history of a problem of the culture at Pan American World Airway before they fixed what was broken. This appeared to be a part of the culture of many Pan American World Airways captains at the time.

1

Accident report

- Date: 22 July 1973

- Time: 22:06

- Type: Boeing 707-321B

- Operator: Pan American World Airways

- Registration: N417PA

- Fatalities: 10 of 10 crew, 68 of 69 passengers

- Aircraft fate: Damaged beyond repair

- Phase: En Route

- Airport (departure): Papeete-Faaa Airport (NTAA), French Polynesia

- Airport (arrival): Los Angeles International Airport, CA (KLAX), USA

2

Narrative

The following narrative is from the excellent book, Sky Gods, by Robert Gandt. It may be one of the best books on Crew Resource Management ever written. The following is about Pan Am 816, which he refers to as Clipper 802.

Papeete, Tahiti, July 22, 1973. A moonless South Pacific night. The heavily laden Pan Am 707 lumbered toward the runway for takeoff. In addition to her sixty-nine passengers and ten crew members, she carried the great store of jet fuel needed for the flight back to Honolulu. The rotating beacon on the belly of the jet cast a red hue on the tropical grass by the taxiway.

The usual crowd-relatives, fellow tourists, airline employees waited in the open lounge, watching the jetliner depart. The Papeete airport had an informal, open-air ambiance, like something from a Somerset Maugham tale. Travelers hated leaving Tahiti. In a short time the place grew on them, and they wanted to stay.

In the cockpit of the 707, Captain Bob Evarts responded to the checklist. Evarts was a senior captain, now in his last year of a career that had begun in the flying boat days. His first officer, Clyde Havens, was the same age-fifty-nine. His career had been nearly as long as Evarts's, but Havens had never been a captain. Years ago he had failed the upgrade training for the left seat and was relegated to the status of permanent copilot. "Clyde's okay," captains said about Havens. "He's just a little slow."

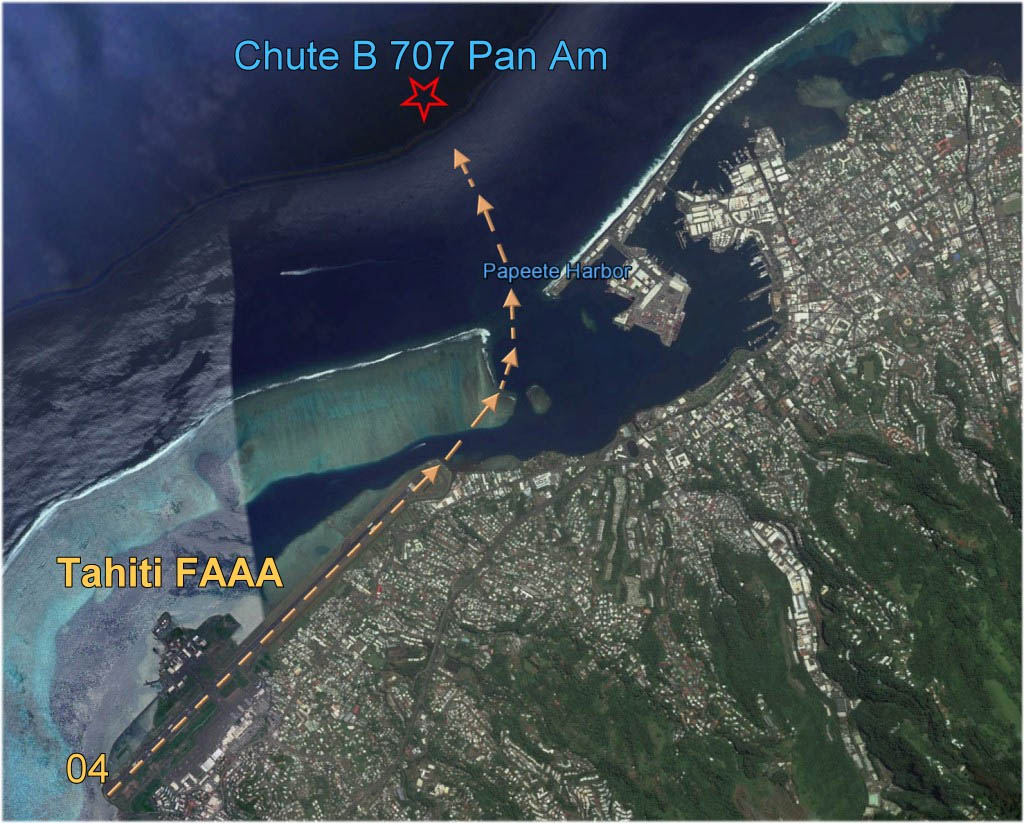

Following the instructions from the tower, they taxied onto the active runway. Beyond the twin rows of white runway lights that stretched for nearly two miles in front of them was the end of the runway. Then an inky blackness. There was no horizon. The sea and the sky melded together in a featureless black void.

"Clipper eight-oh-two," said the Papeete control tower operator, "the wind is two-four-zero at eight knots. You're cleared for takeoff." Havens acknowledged the clearance. The jet began its takeoff roll.

From the airport terminal they watched the 707 trundle down the runway. The noise of the four fan-jets swelled in a crescendo. The jetliner gathered speed, rushing to the distant end of the runway. It lifted and climbed into the blackness beyond the shore. From the terminal there was no way to tell if the jet was climbing, descending, or turning. The lights of the departing 707 twinkled in the black void beyond the shore.

And then, an orange flash.

Seconds later, nothing. The lights were gone. Clipper 802 had vanished from sight.

In the terminal, disbelief. "What happened?"

"Where did it go?"

"Do you think. .. ?"

Airmen hate mysteries. For every accident, they want to know the probable cause.

No probable cause was determined for the loss of Flight 802. Most of the wreckage of the Boeing 707, including the vital flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder-crashproof "black boxes" that capsulized the moments of the jet's last flight-sank to the floor of the Pacific. They were never recovered.

Investigators combed the scant evidence, looking for clues. In the maintenance history of the airplane was a recent wing flap discrepancy. Had the flaps retracted asymmetrically? If so, might it have caused an uncontrollable roll, making the jet plummet downward to the ocean? Another discrepancy involved the windshield heat. Could a windshield have shattered, distracting or blinding or incapacitating the pilots?

Maybe. Or was it something else? Something nonmechanical? One inescapable statistic about aviation accidents was that most were caused by human factors. Since the first flight of the Wright brothers, aviation was a plethora of mistakes waiting to be made-landing short of the runway, forgetting to lower the landing gear or the wing flaps, running out of fuel, misjudging things like altitude, airspeed, distance. Such lapses were always branded with the most searing of aviation indictments: pilot error.

By an extrapolation of logic, investigators could conclude that every accident was somehow the result of human error. Someone should have caught the discrepancy, the circumstances, the procedural omission that permitted an accident to occur. In the final analysis. of aviation mishaps, it always came down to the pilots. Pilots were almost always in the loop of blame, because they had the last vote in every impending calamity.

But that view was simplistic. In the accident equation, it still missed the all-important Why?

A more significant fact was that most fatal airline accidents-more than two-thirds-happened during the takeoff or landing phase. And a disturbingly high proportion of those accidents occurred at night, or in low visibility, and at airports that lacked an ILS-an instrument landing system, an electronic approach path transmitter that guided airplanes precisely down a glide path to the touchdown point on the runway.

Which described the world of Pan American.

Pan Am's planet-wide route system covered the typhoon-scoured atolls of the Pacific, the equatorial republics of South America, the backwaters of Central Africa. Pan Am had the highest exposure to primitive airports of any major airline in the western world. Unlike the domestic carriers that operated exclusively in the comfortable, radar controlled airway system of the United States, Pan Am's jets made daily-and nightly-transits of the world's most backward facilities.

So what happened in Tahiti? No one would ever know for sure. Rob Martinside blamed the "black hole" syndrome. Since aviators first flew at night, there had been a problem with spatial disorientation in the blackness. For the first few seconds after liftoff, as pilots made the transition from gazing outside at runway lights to looking inside at their instruments, they didn't always believe what they saw. It was particularly difficult over an empty, horizonless ocean. A common accident off aircraft carriers was the phenomenon of airmen launching into the black night off the bow of the ship, then inexplicably flying into the water. The cause was visual disorientation-the pilot's flawed senses overruling what he read on his instruments.

But such speculation was blasphemy in Skygod country, particularly when spoken by new-hire know-nothings. You didn't second-guess the actions of a lost crew, particularly when there was no hard evidence in the form of a cockpit voice recorder or flight data recorder. Every trace of evidence from Flight 802, black boxes included, lay 18,000 feet beneath the waves.

The older Pan Am pilots closed ranks around their peers. Give the deceased the benefit of the doubt. Maybe it was a split flap, or a windshield problem. Better to accept such an explanation than to impugn the reputation of a Pan Am captain.

"Bullshit," said Jim Wood, who saw no reason to be charitable. He had seen the Skygods in action. It angered him that no one wanted to confront the real problem. "How many airliners have had accidents because of a split flap- day or night? Virtually none. Or a shattered windshield?"

None.

Wood had his own theory: "It was dark. They took off in a 707 that was heavily loaded and didn't climb fast. They got disoriented and let it fly into the water."

It was a private theory. He had the good sense to keep it to himself.

Source: Gandt, pp. 109-112

3

Analysis

Many on the Internet have speculated about this crash and in most cases the same words are used. A reader who was there and has read the accident report submits the following.

Hi James,

I read with interest your clip on this accident. I was in Tahiti when this accident occurred and it really shook the population of Tahiti. Although I was very young then (5 years old), I still remember it to this day. My mom used to work for UTA (Union des Transport Aerien) and I grew up in the aviation world. The bug got a hold of me early on and never let go. We left Tahiti in 1977 but I return every now and then to visit old friends and show my family how beautiful French Polynesia is. I, recently, decided to dig up what I could find about this accident and as you mentioned, there is limited information on it.

I also retrieved the Final report from the BEA and read it cover to cover (9 pages) since French is my native tongue. Although the speculation of possible instrument failure or spatial disorientation is totally legitimate, it seem that maybe the slats may not have extended for Takeoff as they should have.

A couple of points that are different from your statement verses the final report, which you may find of value.

- Its destination was LAX, not HNL.

- Rest time in Papeete, just over 16 hours after having flown 9 hours on the back side of the clock. Got to the hotel at 6:15, the 4 flight crewmembers got together at 14:00 to have lunch then went to the beach or town. They met back at 18:30 for the van to the airport for a 20:30 departure. The rest (less than 8 hours of quality sleep) they got was inadequate from my point of view.

- The captain was reluctant to take the aircraft with L3 window written up and got into a heated debate with MTX according to witnesses. Maintenance told him, it was an Melleable item as long as the window heat was removed. They sent messages to NYC to confirm that it was okay.

- Captain ordered the maximum fuel to fly at FL 230 to LAX instead of FL 330 in case the window broke apart. He was granted the additional fuel and wound up with a ramp weight of 316,150 lb and a TOW of 315,150 lbs. MTOW for 04 that day was 331,000 lbs. He also requested a clearance to FL 230 from tower. Took an hour and half delay to put on additional fuel and query MTX in New York.

- They did autopsies on two flight crewmembers; the first officer and the Flight engineer. Both bodies had insignificant levels of Carbon Monoxide or alcohol.

- The captain and first officer were both on high blood pressure medication but it did not play a role in this accident.

- The only survivor (witness 19) felt the aircraft vibrating violently shortly after takeoff 2 to 3 times before it banked to the left. (bottom right of page 1151, that was his first testimony 30 July 1973, eight days after the accident). On his second testimony, August 7th 1973, he said the aircraft “tried for his height” right after the runway. Shortly after, it felt as if someone had pulled on the tail and then it lurched forward violently for 2 seconds. That is when he reached for the pillow next to him and assumed a fetal position. He said the vibrations was “ playing havoc with such a big machine”.

- When taking off on runway 04 you are facing the Port of Papeete. There is plenty of lights in front and to the right (up in the hills). The testimonies of the witnesses all mention a weak pitch setting (less than 15 degrees) upon rotation which puts doubt in my mind about disorientation.

- The entire nose gear was found in the retracted position. The left tire was deflated (0 psi) but not the right (75 psi). This leads me to believe the crew may have taken off at an airspeed past the tire limit. No mention whether the left tire was shredded.

- They found the trailing edge flaps, or sections of, in the 14 degree position (Takeoff).

- They used the entire runway to liftoff according to witnesses. The lone survivor (witness 19) said he saw the green lights at the end of the runway (must have been the runway end lights for 22). He said the takeoff roll was excessively long.

The report did not provide any calculations as to what airspeed would have been required to lift off w/o any slats. The facts the lone survivor provide regarding vibrations leads me to believe the airplane barely hanged on flying straight out. The noise abatement procedure for this runway was to turn left at 500 ft or V2+30 to a heading of 360. Normal bank and climb at optimum speed to join assigned route. If the crew was already past V2 + 30, that may explained this way early turn. If the slats were indeed not extended, that turn could have cause the wing to stall if the airspeed was insufficient and could possibly explain the vibrations in the cabin that the lone survivor described.

The human factors in this accident seem like a huge threat to me:

- lack of proper rest (leadership, workload management)

- captain having a heated discussion with MTX. (flight discipline)

- Language barrier with local help possibly. (communication)

- The captain could have felt pressured because he delayed the flight to add fuel that Pan Am dispatch/MTX did not see as justifiable but went along to keep the operation going.(Leadership)

- The report also states both captain and first officer had issues on their last proficiency checks. (flight discipline)

Other threat: L3 MEL, Thrust reverser on #4 had failed in the open position after landing from Auckland, although it had been reset by the maintenance personnel.

I am trying to enhance my understanding of this accident, learn from the facts and by no means want to disrespect the memory of the Pan Am crew . Any constructive inputs you may have and if you could answer my two questions above, I would be very grateful.

A reader from Tahiti

The reader brings up some very good points, there are a lot of ways this flight could have gone wrong. From my experience flying a military version of this airplane (EC-135J), it is easy to get disoriented at night and if you do that, the airplane is quite willing to roll itself on a wing and lose pitch. It is critically important that the airplane be flown on instruments at night, especially over the water. This was not an isolated case for the airline; Pan Am lost several other Boeing 707s due to poor instrument skills and spatial disorientation:

I think it is plausible that Pan Am 816 was lost due to poor flying skills and inadequate crew resource management.

4

Cause

We don't have an official list of causes but must remember that our aim in building case studies isn't to arrive at conclusive proof (as in a court of law), but to derive lessons to prevent recurrence. In that spirit, I would offer the following as causal: the culture of Pan American World Airways at the time of this accident allowed captains to perform at a substandard level without supervision while discouraging subordinate crewmembers from offering meaningful critique.

In absence of sufficient indices, the Commission had to confine itself to exposing the hypotheses mentioned above and was unable to determine with certainty the causes of the accident.

Source: Journal Officiel, Rapport FInal, ¶5.2

References

(Source material)

Gandt, Robert, Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am, 2012, Wm. Morrow Company, Inc., New York

Journal Officiel, De La Republique Française, Repport Final, de la Commissiond'enquête sur l'accident du Beoing 707 N 417 PA de la Comagnie Pan American World Airways, à Tahiti, le 22 juillet 1973.

NTSB Aircraft Accident Summary,DCA72RZ001, Pan American World Airways 6005, N461PA, July 25, 1971