The VFR traffic pattern can be a dangerous place. The Big Sky Theory never works well, and it especially fails when the "big" sky is narrowed to the confines of an airport traffic area.

— James Albright

Updated:

2016-12-06

It is true that neither aircraft in this mishap were equipped with TCAS or ADS-B and that the tower controller made several crucial mistakes. But it may also be true that the midair could have been avoided had the pilots of either airplane had better situational awareness and used better visual clearing techniques.

We often downplay the complexity of a "simple" VFR traffic pattern because it is one of the very first skills we learn as pilots. If they let a student pilot do it solo, how hard can it be? The NTSB hangs the blame for this midair on the tower controller and the limitations of the "see and avoid" concept. That might be as it should be, but that doesn't do the pilots any good. "Blameless" or not, they are all dead.

I don't mean to be callous, only to illustrate that, as pilots, there are things we can do to stack the odds in our favor. I believe the defining attribute of a fighter pilot is the ability to keep "Good SA" in three dimensions, to be situationally aware of the airplane's environment. That environment includes other aircraft. Had any of the three pilots involved in this midair kept a 3-D map of the pattern and aircraft in mind, this midair could have been avoided.

1

Accident report

First Aircraft:

- Date: 16 August 2015

- Time: 11:03

- Type: Rockwell Sabreliner 60SC

- Operator: BAE Systems Technology Solution & Services

- Registration: N442RM

- Fatalities: 4 of 4 crew, 0 of 0 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airports: (Departure) San Diego Brown Field Municipal Airport, CA (SDM/KSDM), USA; (Destination) San Diego Brown Field Municipal Airport, CA (SDM/KSDM), USA

Second Aircraft:

- Type: Cessna 172M Skyhawk

- Operator: Private Flight

- Registration: N1285U

- Fatalities: 1 of 1 crew, 0 of 0 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: En route

- Airports: (Departure) San Diego Brown Field Municipal Airport, CA (SDM/KSDM), USA; (Destination) San Diego Brown Field Municipal Airport, CA (SDM/KSDM), USA

2

Narrative

- On August 16, 2015, about 1103 Pacific daylight time, a Cessna 172M, N1285U, and an experimental North American Rockwell NA265-60SC Sabreliner, N442RM (call sign Eagle1), collided in midair about 1 mile northeast of Brown Field Municipal Airport (SDM), San Diego, California. The pilot (and sole occupant) of N1285U and the two pilots and two mission specialists aboard Eagle1 died; both airplanes were destroyed. N1285U was registered to a private individual and operated by Plus One Flyers under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 91 as a personal flight. Eagle1 was registered to and operated by BAE Systems Technology Solutions & Services, Inc., for the US Department of Defense as a public aircraft in support of the US Navy. No flight plan was filed for N1285U, which originated from Montgomery-Gibbs Executive Airport, San Diego/El Cajon, California. A mission flight plan was filed for Eagle1, which originated from SDM about 0830 and was returning to SDM. Visual meteorological conditions prevailed at the time of the accident.

- On the morning of the accident, the SDM airport traffic control tower (ATCT) had all control positions (local and ground control) in the tower combined to the local control position. The position was staffed by a qualified local controller (LC)/controller-in-charge (CIC) who was conducting on-the-job training with a developmental controller (LC trainee) on the local control position. The LC trainee was transmitting control instructions for all operations; however, the qualified LC was closely monitoring the LC trainee’s actions and was responsible for all activity at that position.

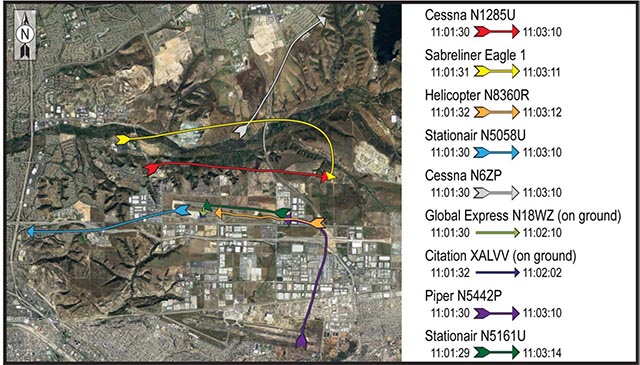

- According to air traffic control (ATC) radar and voice communications data, the pilot of N1285U contacted the SDM ATCT at 1049:44 and requested touch-and-go maneuvers in the visual flight rules (VFR) traffic pattern. N1285U was inbound about 6 miles to the northeast of SDM, at an indicated altitude of 2,600 ft. About that time, another Cessna 172 (N6ZP) and a helicopter (N8360R) were conducting operations in the VFR traffic pattern, and a Cessna 206 Stationair (N5058U) was inbound for landing after carrying parachutists to a local drop zone about 5 nautical miles (nm) east of the field.

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

This was a fairly complicated situation, given there were so many airplanes in the same pattern. The Sabreliner (Radio call: "Eagle1") pilots would have been listening to reports of two Cessnas 172's (Radio calls: "Cessna 1285U" and "Cessna N6ZP"), a Cessna 206 (Radio call: "Stationair 5058U") and a helicopter (Radio call: "Helicopter 8360R").

- At 1057:22, the LC trainee cleared the pilot of N1285U for a touch-and-go on runway 26L, and at 1057:27, the pilot acknowledged the clearance.

- At 1059:04, when Eagle1 was 9 miles west of SDM, the flight crew contacted the SDM ATCT and requested a full-stop landing. Throughout Eagle1’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recording, the pilot, seated in the left seat, was communicating on the radio and responding to checklists, consistent with that pilot acting as the pilot monitoring and the copilot, seated in the right seat, acting as the pilot flying. The LC trainee instructed the Eagle1 flight crew to enter a right downwind for runway 26R at or above an altitude of 2,000 ft mean sea level (msl).

- At 1059:33, the qualified LC terminated the LC trainee’s training and took over control of communications due to increased traffic. The LC trainee signed off the position but remained in the tower to observe operations. From this time until the collision occurred (about 1103), the LC was controlling nine aircraft.

- During the next 2 minutes, the LC made several errors that were either corrected by him or by the pilots under his control. At 1059:44, after the pilot of N6ZP completed a touch-and-go on runway 26R, he requested a right downwind departure from the area. The LC did not respond. At 1100:23, the LC instructed, “stationair five eight uniform two six right cleared for I’m sorry two six left cleared for takeoff.” At 1100:29, the pilot of N5058U stated, “uh I’m sorry was that for five eight uniform?” The LC then cleared the pilot of N5058U for takeoff from runway 26L. At 1100:36, the LC transmitted, “helicopter six zero romeo there is a ces ah cen ah correction stationair just ahead they are going to the right runway base leg for two six left.” At 1100:46, the pilot of N6ZP repeated his request for departure; the LC then approved N6ZP’s departure request, and N6ZP departed the traffic pattern in a northeasterly direction. At 1100:53, the LC instructed the helicopter pilot, “helicopter six zero romeo listen up turn crosswind” before correcting the instruction 4 seconds later to “turn base.” At 1101:15, the Eagle1 CVR recorded the copilot state, “got one on the runway,” and at 1101:19, the Eagle1 CVR recorded the pilot comment, “wowww. he’s like panicking” (with an emphasis on panicking).

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

Hearing the controller in a panic could be a clue that everyone on frequency needs to be extra cautious.

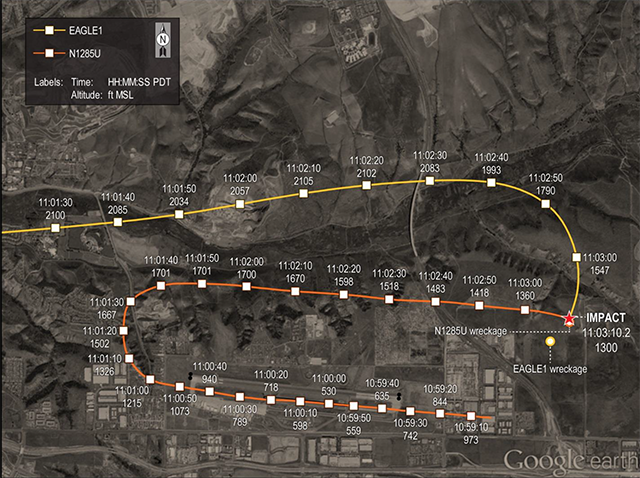

Aircraft in the SDM traffic pattern from about 1101 until the time of the accident, (NTSB Accident Docket, WPR15MA243A

- At 1101:49, the Eagle1 CVR recorded one of the mission specialists seated outside the cockpit ask “see him right there?” At 1102:14, while on the right downwind leg (and, according to radar data, while overtaking N1285U from behind and to the left) and abeam the tower, the Eagle1 flight crew reported to the ATCT that they had traffic in sight to the left and the right of their position. Radar data indicated that N6ZP was to the left of Eagle1 and heading to the northeast, and N1285U was between Eagle1 and SDM, on a closer-in right downwind leg.

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

At this point, the Sabreliner crew appeared to have a good awareness of the two light aircraft in their area. It may have been helpful to articulate the call sign of the aircraft that was a threat because it too was in the landing pattern.

- At 1102:32, the LC instructed the pilot of N6ZP, which he thought was the Cessna on right downwind, to make a right 360 ̊ turn over the airport and rejoin the downwind. Despite the fact that, at that time, N6ZP was 2.3 nm northeast of the airport and was departing the area, the pilot of N6ZP acknowledged the instruction and initiated a right turn. At the same time, Eagle1’s CVR recorded the pilot asking, “you still got the guy on the right side?”

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

There is no doubt the controller made a mistake, but the pilot of N6ZP could have helped things a bit by reminding the controller that he was the departing aircraft and doing a 360° turn didn't make sense. The pilots of the other two aircraft could have also spoken up had they recalled which airplanes were in the landing pattern.

- At 1102:42, the LC instructed the Eagle1 flight crew to turn base and cleared the flight to land on runway 26R. The LC stated in the postaccident interview that after he cleared the Eagle1 flight crew to land, he looked up to ensure that Eagle1 was turning base and noticed that the Cessna on downwind (which he still thought was N6ZP) was continuing on its downwind track and had not begun the turn that he had issued. At 1102:56, the LC contacted the pilot of N6ZP, and the N6ZP pilot replied by stating that he was turning. At 1102:59, Eagle1’s CVR recorded the pilot comment “I see the shadow but I don’t see him.”

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

Jet aircraft typically use a 1,500' AGL traffic pattern, while light aircraft will use a 1,000' AGL traffic pattern. The light aircraft pattern tends to be inside the jet pattern, which means the light aircraft can be vulnerable to the jet descending on top of them on final. Jet aircraft can compound the problem by flying tight patterns that can turn on top of the light aircraft, obscuring the view of both for both.

- At 1103:04, the LC transmitted “November eight five uniform”; this was the first ATC transmission with N1285U in almost 6 minutes and the first communication between the LC and N1285U. At 1103:07, the pilot of N1285U acknowledged the transmission, “eight five uniform.” At 1103:08, the LC asked the pilot of N1285U if he was still on the right downwind leg. The pilot of N1285U did not respond. The LC and the LC trainee then witnessed Eagle1 and N1285U collide.

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

3

Analysis

- The white- and yellow-colored Cessna 172M was a high-wing, four-seat airplane manufactured in 1976 and [ . . . ] was equipped with a rotating beacon light, anticollision strobe lights, navigation position lights, a landing light, and a taxi light. The operational status of each lighting system at the time of the accident could not be determined. N1285U was not equipped with a traffic advisory system (TAS), traffic alert and collision avoidance system (TCAS), or automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast (ADS-B) equipment or displays.

- The white-colored North American Rockwell NA265-60SC Sabreliner was a low-wing, five-seat airplane [ . . . ] was equipped with anticollision lights on the vertical tail and under the fuselage just forward of the main wheel well, wing ice inspection lights, strobe and position lights on the tail cone and each wing tip, and landing-taxi lights forward of the nose landing gear. The operational status of each lighting system at the time of the accident could not be determined. The Sabreliner was not equipped with a TAS, TCAS, or ADS-B equipment or displays.

- The 1053 SDM automated weather observation included wind from 310o at 6 knots, visibility 10 statute miles, clear skies, temperature 33o C, dew point 19o C, and an altimeter setting of 29.87 inches of mercury.

- The NTSB’s investigation examined the ability of the N1285U and Eagle1 pilots to see and avoid the other aircraft. To determine approximately how each aircraft would appear in the pilots’ fields of view, the position of the “target” aircraft in a reference frame attached to the “viewing” aircraft must be calculated. This calculation depends on the positions and orientation (pitch, roll, and yaw angles) of each aircraft, as well as the location of the pilots’ eyes relative to the cockpit windows. Position and orientation information for both airplanes was estimated based on an analysis of the radar data, combined with models of each airplane’s aerodynamic performance.

- For this study, the relative positions of the two aircraft were calculated beginning at 1100:06.0 and then at 0.05-second intervals up to the collision, which occurred at 1103:10.2. The time, location, and altitude of the collision were determined based on extrapolation of the radar data, the wreckage locations of both aircraft, and the time of the end of Eagle1’s CVR recording.

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

Fighter pilots often talk about "SA" in air-to-air combat as a deal breaker. If you lose situational awareness in the three-dimensional arena of air combat, you can lose it all. They also talk about the unique challenge of "DACT," dissimilar air combat training. When mixing aircraft types the dissimilar speeds and maneuverability can turn training into lethal situations. The VFR traffic pattern can be just as deadly. The Saberliner's copilot would have been hard pressed to see the Cessa seconds before impact. But had he kept "good SA" he would have realized the airplane was on a converging course. At this point another staple of "DACT" would have been useful, and that is a "knock it off" call. If you are about to turn and descend for you base turn, you should be certain the airspace is yours.

Most aircraft that are not built for air combat will have vision obscurations making "target acquisition" difficult. Many jets have small windows, further complicating the problem. High wing aircraft, like the Cessna 172, have a unique challenge when sharing the traffic pattern with jets, typically flying 500' above them. Conflicting traffic can be obscured by the wing. There are two solutions. First, you need to keep a three-dimensional view of the pattern and any conflicting traffic. You may lose sight of an aircraft but you should visualize where that airplane will be as time progresses. Second, you need to move your head. The fighter pilot reminds us to "keep your head on a swivel" when looking for your "bogie." Do that, but don't forget to look around those posts too.

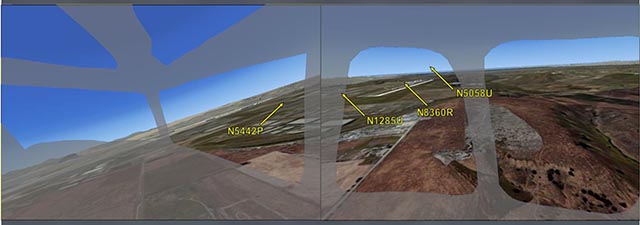

- At 1101:43.1, N1285U would have been located just to the left of the window post separating Eagle1’s R2 and R3 windows, and N5058U would have been just to the right of this post (see figure 7a). Eagle1 would have appeared in the left window of N1285U, just below the wingtip (see figure 7b). Eagle1 and N1285U were both on the right downwind leg for runway 26R, with Eagle1 about 0.4 nm north of N1285U.

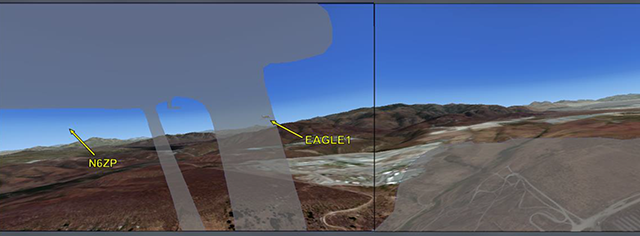

- At 1102:14.0, when the Eagle1 flight crew reported “...right downwind abeam. traffic to the left and right in sight,” Eagle1 was at about 2,110 ft, 1.3 nm north and 0.4 nm west of the runway 26R threshold. N6ZP would have appeared in Eagle1’s L1 window and was the only aircraft to Eagle1’s left. N1285U would have appeared in Eagle1’s R3 window. N1285U was descending through 1,650 ft, about 0.7 nm north and 0.5 nm west of the runway 26R threshold. Eagle1 would have remained obscured from the N1285U pilot’s view by the left wing.

- At 1103:08.0, when the controller asked the N1285U pilot if he was still on downwind, Eagle1 and N1285U were about 0.1 nm apart. N1285U may have been obscured by the post between Eagle1’s R1 and R2 windows, and Eagle1 may have been obscured by N1285U’s window post (see figures 10a and 10b).

Source: NTSB Factual Report, WPR15MA243A

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be: The local controller's (LC) failure to properly identify the aircraft in the pattern and to ensure control instructions provided to the intended Cessna on downwind were being performed before turning Eagle1 into its path for landing. Contributing to the LC's actions was his incomplete situational awareness when he took over communications from the LC trainee due to the high workload at the time of the accident. Contributing to the accident were the inherent limitations of the see-and-avoid concept, resulting in the inability of the pilots involved to take evasive action in time to avert the collision.

Source: NTSB Accident Final Report

References

(Source material)

NTSB Accident Docket, WPR15MA243A/B, Accident Final Report, Factual Report, Pilot/Operator Aircraft Accident/Incident Report, and others, Dated on or about August 16-17, 2015