In 1982, the United States Thunderbirds crashed in a four-ship line abreast formation, on the bottom side of a loop during a practice session. The Thunderbirds have had a total of 18 crashes, three of those during live public airshows. There have been a total of 21 aircrew fatalities. The 1982 crash provided the Air Force with an important wakeup call, but in my opinion, the Air Force learned the wrong lesson and there have been four more incidents since then.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-09-15

Major Norm Lowry (top),

Captain Pete Peterson (left),

Captain Willie Mays (right),

and Captain Mark Melancon (bottom),

from the US Air Force Air Collection

As we will see, Major Norman Lowry made a series of mistakes and led the formation into the ground. The evidence was clear from the start, but the Air Force couldn’t admit their best pilots were flawed, so they invented a cause to deflect the blame. In my opinion, Major Lowry made the mistake, but he was not the cause of the crash. The Air Force was.

It would be tempting to say that any possible lessons only apply to those in the air demonstration business, those who fly with substantially reduced safety margins with the sanction of the organizations they represent. But if you really drill down into the cause and resulting investigation of the 1982 event, you will see the lessons are universal to anyone who flies for a living. So, let’s take a look at what happened, the subsequent investigation, the coverup, and the lessons to be learned for those of us flying airplanes professionally.

Date: 18 January 1982

Type: Four Northrop T-38 Talons, T-38A

Registrations: 68-8156, 68-8175, 68-8176, 68-8184

Fatalities: 4 / 4

Aircraft fate: destroyed

Location: Indian Springs, NV,

1

The four-ship line abreast loop

What happened

The basic maneuver

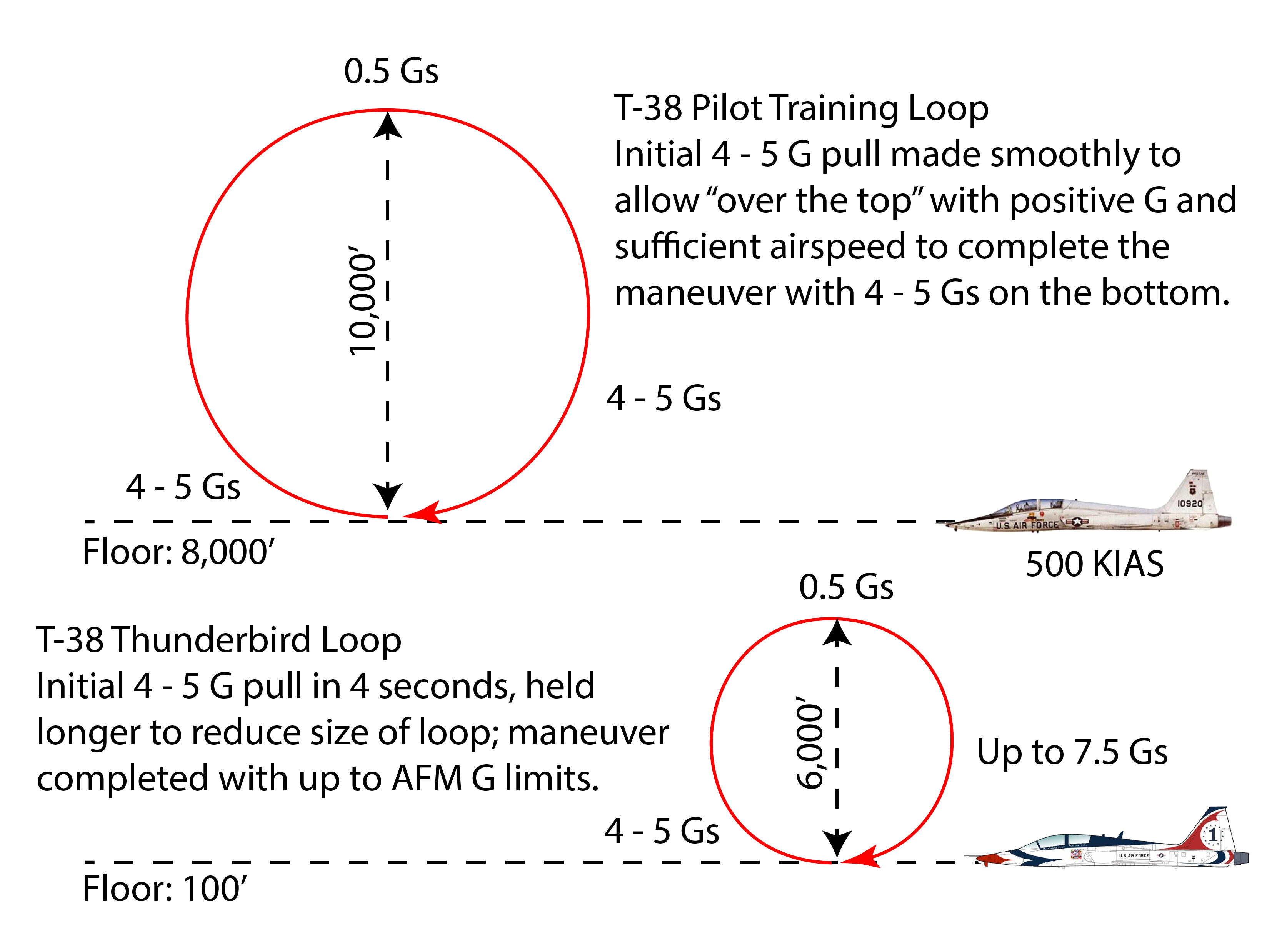

The basic loop is a primary maneuver taught during Air Force pilot training, and I learned to do it as instructed by the Air Training Command Regulation (ATCR) 51-38:

(1) Enter the lop with an entry airspeed of 500 KIAS and power set at military.

(2) The loop is a 360° turn in the vertical plane. Elevator is the basic control; however, aileron and rudder are used to maintain directional control coordination. Attain the preselected entry airspeed with the power set and enter a 4 to 5 G pullup. Use primarily outside references to maintain wings level during the maneuver, permit the aircraft to accelerate while gradually increasing the load factor to 4 to 5 Gs as you complete the loop. You should plan on the maneuver requiring 10,000 feet of altitude from start to the highest point.

[ATCR 5-38, para. 4-8.h.]

As a student, we began our practice at the prescribed airspeed and power setting. “Military” is the power setting attained with the throttles full forward, short of activating the after burners. As proficiency is gained, the power comes back to 550° EGT. We were not expected to make the loop appear symmetrical, only to keep enough flying speed at the top to keep the aircraft fully controllable, the Gs within the prescribed limits, and to keep the airplane in that 10,000 foot box. This required a great deal of finesse in the initial pull. Instructors trained to the same limitations, but often challenged themselves to loops with lower entry speeds and higher Gs. One thing was absolute: our minimum altitude – “the floor” – was 8,000 feet. If you go below the floor, you are considered a “mort” – a mortality in terms of the regulation.

Note that with the T-38 loop as taught most Air Force pilots of the time, the initial 4 – 5 G pull is made smoothly and gradually reduced so as to arrive “over the top” inverted with positive G on the aircraft and enough flying speed to keep flying and pull the nose down. You learn this through practice. If done correctly, you end up where you started after pulling 4 – 5 Gs on the backside. We normally did this single ship, but doing a loop in a two-ship formation was perfectly okay. I don’t think I’ve ever done this four-ship.

The Thunderbird maneuver, as designed

The loop maneuver as flown by the Thunderbirds have several key differences, most notably the starting and ending altitude: just 100 feet. The maneuver is completed using much less vertical altitude – 6,000’ versus 10,000’ – by making the initial 4-5 Gs more quickly and holding those Gs longer. That gets you vertical with more speed and G available. Once again, you want to end up “over the top” inverted with positive G on the aircraft. Since you are at a lower altitude, you will need more Gs to complete the maneuver.

The line abreast loop is extremely dangerous for the formation since each wingman pilot has to turn their heads 90° to the side during this high G maneuver. Only the leader has the benefit of monitoring airspeed and altitude, the wingmen will have the focus exclusively on lead. If lead makes a mistake, they are unlikely to catch that mistake before it is too late. While it looks spectacular, it is dangerous. As a result of this accident, the Thunderbirds no longer fly their loops in the line abreast formation. I don’t think the Blue Angels ever did.

The Thunderbird maneuver, as flown on this date

The lead aircraft had a Velocity-Gs-Height recorder but the tape was unusable. The three remaining aircraft had a type of Flight Data Recorder, but none had the required tapes installed. All four aircraft had Modular Strain Recorders, but none survived impact. A radio recorder used to record radio transmissions was found to be nonfunctional. Because of all this, “It quickly became apparent that the video tape would provide the most meaningful aircraft performance data on the mishap maneuver.” [p. J-1-2]

The accident board used that video tape to determine what happened during the loop:

Entry (0.0 degrees).

(a) Time: 0.0 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 3286 feet MSL; 178 feet AGL.

(c) Airspeed: 390 KIAS.

(d) Entry Gs: 3.7 in four seconds.

(e) Remarks: Airspeed and Gs are below target values, but are not abnormally low.

090 Degrees.

(a) Time: 11.7 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 6500 feet MSL; 3392 feet AGL.

(c) Airspeed: 290 KIAS.

(d) Gs: 2.5.

180 Degrees.

(a) Time: 24.0 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 9750 feet MSL; 6642 feel AGL.

(c) Airspeed: 140 KIAS.

(d) Gs: 0.5.

(e) Remarks: Loop appears normal at this point.

220 Degrees. Gs less than normal at this point. This would result in the 270 degree point being reached in the same time, but at a higher than normal velocity and lower than normal altitude.

270 Degrees.

(a) Time: 34.8 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 6700 feet MSL; 3592 feet AGL.

(c) Airspeed: 310 KIAS.

(d) Gs: 2.6.

(e) Remarks: Although the Gs are slightly higher than normal for the 270 degree point, the airspeed is much greater, and the pilot should be commanding more Gs to successfully recover the aircraft. The maximum G available is 4.2 Gs.

334 Degrees.

(a) Time: 42.1 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 3389 feet MSL; 381 feet AGL.

(c) Airspeed 424 KIAS.

(d) Gs: 7.2.

(e) Remarks: G available is 7.8. High G loading is maintained until impact.

357 Degrees.

(a) Time: 43.4 seconds.

(b) Altitude: 3108 feet MSL; 0 feet AGL.

(c) Airspeed: 416 KIAS.

(d) Gs: 7.0.

(e) Remarks: Ground impact. G available is 7.5.

[pp. J-1-6 – J-1-8]

2

The investigation

The cause was immediately apparent

Investigators quickly determined what happened.

18 Jan 1982, Aircraft Mishap Investigation, Performance Evaluation

The first 180 degrees of the loop appeared normal. At approximately the 220 degree point, lower than normal G load is attained. Consequently, the 270 degree point is reach at a lower than normal altitude and higher than normal airspeed. From the 270 degree to the 310 degree point, the Gs are slightly higher than normal, but still less than required for recovery. From the 334 degree point to impact, 7.0 to 7.2 Gs were maintained. This was still insufficient for successful recovery. An additional ten feet of altitude was required for lead aircraft to clear the terrain with the established turn rate.

[pp. J-1-6 – J-1-8]

The leader flew the formation into the ground. But why? The report was incredibly thorough when examining the wreckage and individual systems. Components, including the stabilizer trim actuators, were identified and any damage correlated with the crash impact or post-impact fire. The report concludes:

THERE IS NO EVIDENCE OF MECHANICAL OR ELECTRICAL FAILURE OR ANY CONDITION THAT WOULD PRECLUDE NORMAL OPERATION OF EXHIBIT ACTUATORS PRIOR TO AIRCRAFT IMPACT.

[pp. I-9 – I-12]

3

The coverup

Good intentions, sure, but still dishonest

The official explanation

The USAF Thunderbirds were a part of the Tactical Air Command, which at the time was led by General Wilbur Creech, a decorated combat pilot with missions in the Korean and Vietnam wars. I imagine it would be a hard pill to swallow if the official explanation of the crash was pilot error, but the report clearly pointed to that direction. The report was written to allow the desired headlines:

Findings.

Finding 1. After four routine formation practice maneuvers, the flight leader initiated a line abreast loop.

Finding 2. Entry parameters were met, and no significant deviations were noted during the first half of the loop.

Finding 3. For an undetermined reason, the leader did not achieve sufficient turn radius during the last half of the maneuver. (CAUSE)

(a) Most probable cause was a malfunctioning pitch trim system which inhibited normal nose rotation and focused the pilot’s attention.

(b) A foreign object may have lodged in the flight control mechanism to inhibit or preclude sufficient nose rotation.

Finding 4. As a result, all four aircraft impacted the ground and were destroyed.

Finding 5. There were no ejection attempts and all four pilots were fatally injured.

[p. T-15]

The news then became that the crash was caused by an aircraft malfunction in the stabilizer trim system.

The Air Force has concluded that a mechanical failure in one plane, combined with the strict discipline followed by the pilots of three others, led to the deaths of four members of its Thunderbird air demonstration team on Jan18. The mechanical failure involved a jammed stabilizer, the component that keeps a plane steady in flight, on the tail of Thunderbird One, the T-38 training jet being flown by Major Normal L. Lowry 3d, the Air Force said in a report released earlier this month.

[Air Force Times, April 11, 1982]

The problem with the official line

I attended the USAF Aircraft Mishap Investigation Course in 1985 where we were taught how to investigate aircraft accidents and how to write the reports. The 1982 Thunderbirds accident report was one we had to dissect. I read the report carefully and many in my class came to the same conclusion: the investigation found no evidence of a malfunctioning pitch trim system and yet that was cited as the most probable cause. Our instructor emphasized that if the T-38 had a pitch trim system that could cause such a failure, then every T-38 in the inventory needed to be grounded pending inspection. The T-38 at the time was the primary advanced jet trainer and we had over 600 in the inventory. That never happened.

The apparent coverup

There was controversy surrounding the video tape, which the Air Force had refused to release. On April 4, 1984, the families of the pilots and a major news channel filed suit in federal court to have the video tape released. Five days later, General Creech informed his Judge Advocate General that he ordered “the fireball portion” of every copy of the video tape erased.

I suppose you can argue that erasing the fireball portion of the tape makes it less sensational for the news and perhaps the kinder thing to do in respect for the victims and their families. But regardless of motive, it makes it appear the Air Force was attempting to coverup the real cause of the crashes. Even to this day, over forty years later, you are likely to read the crash was caused by a jammed stabilizer. It was not.

I believe the Air Force tried to blame the crash on mechanical failure, rather than tarnish the image of their premier air demonstration team. But the report itself counters that argument. If I were writing the report, my statement of causes would be as follows:

1) The United States Air Force failed to exercise sufficient oversight of the Air Force Air Demonstration Squadron – The Thunderbirds.

2) The Air Force failed to fully investigate and institute corrective actions following the many previous Thunderbirds accidents.

3) The Thunderbirds failed to incorporate sufficient safety margins in the design of many of their air demonstration maneuvers.

4) The Thunderbirds failed to incorporate robust and effective methods to abort maneuvers when beyond design parameters.

5) The Thunderbird Lead pilot failed to properly execute the line abreast loop, resulting in the loss of all four aircraft and pilots.

4

The lessons

Applicable to all aviators, especially professional aviators

On the surface, it may seem that any lessons here only apply to air demonstration teams who fly with very thin safety margins. But there are lessons for all of us aviators.

Lesson: You are not as good as you think you are.

Aviation tends to attract people with strong egos, or perhaps, aviation instills into people strong egos. Either way, we tend to think we can do just about anything. As good as you are, please consider the case of Major Norman Lowry III. By all accounts, he was an outstanding pilot. He flew 264 combat missions in Vietnam and was named to become the new Thunderbird lead pilot in 1981. By January 17, 1982, he had flown 97 practice Thunderbird mission, including over 500 practice loops. And yet he died the next day.

I consider myself an average pilot. I think Lowry was an exceptional pilot. Average or exceptional, none of us are perfect. I think the lesson for all of us is to be more skeptical about our abilities. When presented with a flying task, such as a low altitude loop, we need to ask ourselves a bunch of “what if” questions. Someone on the Thunderbird team, most notably the lead pilot, should have asked, “what if the lead pilot misses an airspeed, G level, or altitude? Is there a way to increase the safety factor or should we remove the maneuver from our play list?”

You probably don’t have such narrow safety margins in your day-to-day flying, but you do have work to do here. You probably haven’t flown over 500 loops in a high performance jet, but there are things you do routinely where complacency can get the best of you. Even if you’ve flown 500 instrument approaches down to minimums without a problem, for example, you need to approach number 501 with the understanding it could be your last.

Lesson: You are not as good as the organization tells you.

I can imagine that putting on the Thunderbirds flight suit provides quite an ego boost and maybe necessary for what is required during an air show. After a while, you believe. You don’t have to be a Thunderbird or Blue Angel to have this attitude instilled in you. One of my Air Force squadrons routinely violated aircraft limitations based on the pilot’s judgment. The squadron and the wing above it condoned this, saying we were better than the lowly civilians on the outside. Once I became a civilian, I discovered that unfounded snobbery is not solely a military quality. There are countless examples; here are some of my favorites.

- A simulator instructor thinks he or she is the best there is, because he or she has the type rating, the instructor rating, and teaches. The fact he or she may not have any airplane hours as the pilot in command will not temper their attitude. We hired one with this attitude and he ended up being my worst hiring decision ever.

- I’ve known pilots who just checked out in the newest model of a manufacturer’s lineup, and believe that makes them better pilots than anyone flying something older. “Oh, you fly a GIII? Someday you will work up to at GIV, then you’ll really know what you are talking about.”

- I once had to fly in the right seat of a Challenger 604 after its tail was replaced. Bombardier provided a test pilot to fly the aircraft, and I was there as a safety pilot. The pilot introduced himself as a senior test pilot and that he had flown many 604s straight out of the factory. Our company director of maintenance, who would sit in the jump seat, rolled his eyes at that. I suppose the senior test pilot was trying to assure us that he had everything under control. One of the maneuvers was to put a sustained 2 G pull on the aircraft. “That’s one of those silly maneuvers,” he explained, “that nobody does because we don’t have a G meter.” When I suggested we fly a 360° turn at 60° of bank, he said, “I guess that might work.” One of the test maneuvers was an approach to stall warning. He tried to milk the recovery with minimum loss of altitude and got us into a stall. I took the airplane from him and flew us home.

You would have to be a very disciplined (and humble) pilot to resist the temptation to think you are, “the best of the best,” when your job title and your boss keep telling you that. If you are tempted by the notion, keep in mind that the NTSB accident docket is filled with the names of pilots who were the best of the best.

5

Postscript

Are things any better today?

In the forty-plus years since the line abreast formation crash, things have gotten better for the Thunderbirds by way of technology. As a result of the crash, the T-38s were replaced by F-16s, which I am told is easier to fly. Another great benefit of the F-16 is in the Head Up Display. Wingmen now have more easier access to flight information while flying in formation.

Things are also better in that the Thunderbirds no longer fly the line abreast loop. I worry, however, that they think they’ve fixed the problem by deleting one maneuver from the lineup. But are there other things they do that should be deleted or improved?

I mentioned at the outset that Major Lowry flew the formation into the ground, but that wasn’t the cause of the crash. The Air Force was. One of the problems with an organization that chooses to cover up mistakes rather than admit its operators are not perfect, is they turn a blind eye to the more systemic problems. I think had the Air Force taken any of the previous Thunderbird accidents more seriously and looked for systemic problems, the line abreast loop would have been abandoned long ago and the crash at Indian Springs may not have ever happened.

Can anyone in today’s Air Force safety system raise a red flag about the premier air demonstration team and expect to be taken seriously? I hope so.

References

(Source material)

“Air Force finds mechanical failure led to crashes of flying team,” Air Force Times, April 11, 1982.

USAF Mishap Report, T-38A 68-8156, 68-8175, 68-8176, 68-8184, Indian Springs, NV, 18 January 1982, dated 4 Mar 1982