This midair collision changed everything about air traffic control and the concept of "see and avoid" for high altitude operations. The Civil Aeronautics Board missed the actual cause in the "Probable Cause" section of their report but got it right in the narrative: ". . . Seeing other aircraft in flight is difficult."

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-07-20

As is the case with many of these reports, don't look for the listed cause but look for what is done as a result. After this mishap, a five-year plan to modernize air traffic control was begun and the weak Civil Aeronautics Administration was replaced by the Federal Aviation Administration. The FAA was given total authority over airspace in the United States.

So what can we learn from this as pilots? If two relatively slow moving aircraft possibly followed by dirty exhaust trails fail to see and avoid, what are your odds moving in faster, relatively invisible aircraft? The lessons of this mishap and of the Big Sky Theory is that see and avoid is a last line of defense. Anything you can do to keep your aircraft in a predictable position and on an IFR flight plan will improve your odds.

1

Accident report

Lockheed

- Date: 30 June 1956

- Time: 1031 PST

- Type: Lockheed 1049A

- Operator: Trans World Airlines, Inc.

- Registration: N6902C

- Fatalities: 70 of 70 total

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: En route

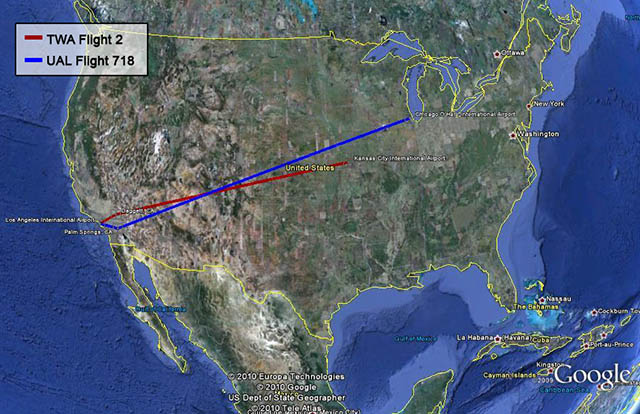

- Airport (Departure): Los Angeles International Airport

- Airport (Destination): Kansas City, MO

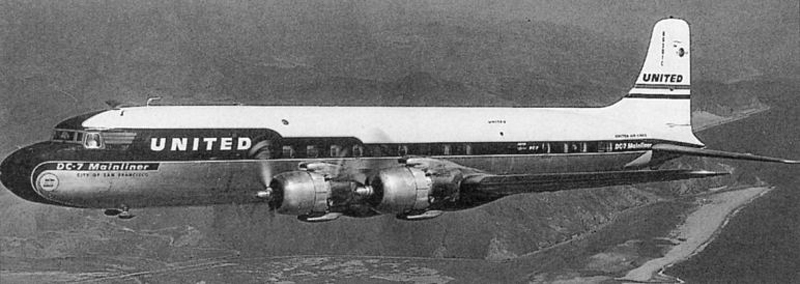

Douglas

- Date: 30 June 1956

- Time: 1031 PST

- Type: Douglas DC-7

- Operator: United Air Lines, Inc.

- Registration: N63234C

- Fatalities: 58 of 58 total

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: En route

- Airport (Departure): Los Angeles International Airport

- Airport (Destination): Chicago, IL

Note: "United Air Lines" was later rebranded "United Airlines." The 1956 CAB report mixes this up a few times, as can be seen in the cited material, which follows.

2

Narrative

- As requested, the flight, after takeoff, contacted the Los Angeles tower radar departure controller, and was vectored through an overcast which existed in the Los Angeles area. After reporting "on top" (2,400 feet) the flight switched to Los Angeles Air Route Traffic Control Center.

- At 0921, through company radio communications, Flight 2 reported that it was approaching Daggett and requested a change in flight plan altitude assignment from 19,000 to 21,000 feet. ARTC (Los Angeles Center) advised they were unable to approve the requested altitude because of traffic (United Air Lines Flight 718). Flight 2 requested a clearance of 1,000 feet on top. Ascertaining from the radio operator that the flight was then at least 1,000 on top, ARTC cleared the flight.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, ¶1

There wasn't a lot of air traffic back then but this crew was made aware that United Flight 718 was in the area at 21,000 feet. The "On Top" clearance allowed them to fly any altitude of their choice, so long as they were at least 1,000 feet above clouds.

- At 0959 Trans World 2 reported its position through company radio at Las Vegas. It reported that it had passed Lake Mohave at 0955, was 1,000 on top at 21,000 feet, and estimated it would reach the 321-degree radial of the Winslow omni range station (Painted Desert) at 1031 with Farmington next. This was the last radio communication with the flight.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, ¶1

- After takeoff the flight contacted the Los Angeles tower radar controller who vectored it through the overcast over the same departure course as TWA 2. United 718 reported "on top" and changed to Los Angeles Center frequency for its en route clearance.

- Flight 718 made position reports to Aeronautical Radio, Inc., which serves under contract as United company radio. It reported passing over Riverside and later over Palm Springs intersection. The latter report indicated that United 718 was still climbing to 21,000 and estimated it would reach Needles at 1000 and Painted Desert at 1034.

- At approximately 0958 United 718 made a position report to the CAA communications station located at Needles. This report stated that the flight was over Needles at 0958, at 21,000 feet, and estimated the Painted Desert at 1031, with Durango next.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, ¶2

The United crew was not informed about the TWA flight. Air traffic control was aware of both flights, but assumed TWA was operating visually because they had a "on top" clearance.

- At 1031 an unidentified radio transmission was heard by Aeronautical Radio communicators at Salt Lake City and San Francisco. They were not able to understand the message when it was received but it was later determined by playing back the recorded transmission that the message was from United 718. Context was interpreted as: "Salt Lake, United 718 . . . ah . . . we're going in."

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, ¶2

- The L-1049 Constellation crashed in a draw on the northeast slope of Temple butte, which is on the west bank of the Colorado River within the Grand Canyon. . . . It was possible, however, to identify a sufficient number of parts to show that with the exception of the L-1049 empennage, portions of the aft fuselage, and light pieces of aft cabin interior, all of the aircraft was at the main wreckage area. Here several pieces of the DC-7 were located. All of these were identified as being parts of the DC-7 left outer wing structure.

- The main wreckage area of the DC-7 was located 1.2 statute miles northwest of the L-1049 area.

- Results of [the investigation] disclosed several areas of damage which conclusively establish that [collision] did occur. . . . One of the significant areas involved in the inflight contact was the left outer wing panel of the DC-7. Pieces found represented the wing panel from its tip inboard to station 453, a length of about 20 feet. Much of this structure bore evidence of inflight collision. . . . The final area of important damage was also in the aft fuselage of the L-1049. It was a series of three propeller cuts in the lower and bottom fuselage in the vicinity of the rear baggage compartment.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, pg. 3

3

Analysis

- Both flights were planned as high-altitude operations (above 14,500 feet west of the 100-degree Meridian) which under current regulations and operating specifications permitted them to be planned and flown off airways over direct courses to take advantage of the most favorable weather and wind factors as well as the shortest distance between origin and destination of the long-range nonstop flights.

- United Airlines' operational policy permitted a high-altitude flight to be conducted on an IFR or VFR flight plan but the company did not permit its flights to be flown in instrument weather conditions, regardless of the flight plan, during that portion of the flight off airways. In this regard Trans World Airlines' policy, at the time of the accident, permitted off airways flights in instrument conditions but only on an IFR flight plan with an assigned altitude. When operating 1,000 on top the company required adherence to visual flight rules.

- Approaching Daggett the TWA flight asked for a change in flight altitude from 19,000 feet to 21,000 feet on its IFR clearance, and if unable, 1,000 on top. The TWA radio operator who received this request from the flight called Los Angeles ARTC and at 0921 advised, "TWA 2 is coming up on Daggett requesting 21,000 feet." The Los Angeles controller then contacted the Salt Lake ARTC controller and said, "TWA 2 is requesting two one thousand, how does it look? I see he is Daggett direct Trinidad, I see you have United 718 crossing his altitude - in his way at two one thousand." According to the recording of this conversation the Salt Lake controller replied, "Yes, their courses cross and they are right together." The Los Angeles controller then called the TWA radio operator and said, "Advisory, TWA 2, unable approve two one thousand." At this time the radio operator interrupted and said, "Just a minute. I think he wants a thousand on top, yes a thousand on top until he can get it." After determining from the flight, through the TWA radio operator, that it was then 1,000 on top the Los Angeles controller issued the following amended clearance, "ATC clears TWA 2, maintain at least 1,000 on top. Advise TWA 2 his traffic is United 718, direct Durango, estimating Needles at 0957." The TWA ground radio operator stated that his clearance was given to TWA 2 and it was repeated back to him verbatim by the flight."

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, pg. 7 - 19

A part of "see and avoid" that we understand much better today is it involves "hear and avoid" too. In some parts of the world you are required to broadcast in the blind so that others will know where you are and aircraft can negotiate avoidance. It is a fundamental part of situational awareness.

- The clearance to TWA 2 was to maintain 1,000 feet on top while it was in a control area. . . . the flight was not restricted to any specific altitude in control areas except that it be at least 1,000 feet above the general cloud layer.

- Civil Air Regulations do not provide a definition for 1,000 on-top operation either within or outside controlled airspace; however, with respect to on-top operations in control areas the Flight Information Manual states, "At least 1000 feet on top may be filed in an IFR flight plan, or assigned by ATC in an IFR clearance, in lieu of a cruising altitude. Even though this type of operation places the responsibility for avoidance of collision with other aircraft on the pilot, the flight is an IFR operation and must obtain an amended clearance for a specific altitude before proceeding into IFR weather conditions.

- The present concept for separation of aircraft and avoidance of collision in VFR weather conditions, regardless of flight plan or clearance, depends on the flight crews' ability to visually provide separation between aircraft. Civil Air Regulations expressly place this responsibility on the pilots.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, pg. 7 - 19

- This accident, as nearly all other midair collisions, apparently occurred in visual flight weather conditions and there is no reason to believe the aircraft were not being operated in accordance with cloud separation criteria of visual flight rules.

- Extensive study of most collision accidents has shown that there was an opportunity, of varying degree, for the pilot or pilots to see the conflicting aircraft in sufficient time for them to take evasive maneuvers to avoid the accident.

- Collision studies, including controlled flight tests, have pointed out that seeing other aircraft in flight is difficult. The degree of difficulty is variable with numerous tangible [such as angular limits of cockpit vision or visual range that an object can be seen] and intangible [physiological conditions such as fatigue and training] factors affecting it.

- From the display it is apparent that the L-1049 was within the angular limits of the DC-7 window from the captain's seat during all the flight path situations. . . . The time opportunity with no clouds was 50 to 120 seconds according to the situation being considered. The worst cloud situation could reduce the time opportunity to as low as 12 seconds.

- With respect to the DC-7 first officer's position, the L-1049 was within the angular limits of the DC-7 window during two of the limit considerations and during the early part of the other two. [120 seconds under the first two conditions and 12 to 50 seconds for the other two.]

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, pg. 20 - 23

4

Cause

The Board determines that the probably cause of this mid-air collision was that the pilots did not see each other in time to avoid the collision. It is not possible to determine why the pilots did not see each other but the evidence suggests that it resulted from any one or a combination of the following factors: Intervening clouds reducing time for visual separation, visual limitations due to cockpit visibility, and preoccupation with normal cockpit duties, preoccupation with matters unrelated to cockpit duties such as attempting to provide the passengers with a more scenic view of the Grand Canyon area, physiological limits to human vision reducing the time opportunity to see and avoid other aircraft, or insufficiency of en route air traffic advisory information due to inadequacy of facilities and lack of personnel in air traffic control.

Source: CAA Accident Report SA-320, pg. 24 - 25] Probable Cause

References

(Source material)

Aircraft Crashes Record Office, Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives, (B3A), Geneva, Switzerland

CAA Accident Investigation Report, SA-320, Trans World Airlines, Lockheed 1049A, N6902C, and United Air Lines, Douglas DC-7, N6324C, Grand Canyon, Arizona, June 30, 1956