I've flown a similar aircraft, the Boeing 707, where 7,000 lbs of fuel meant it was time to land. With that much fuel, the captain delayed leaving the holding pattern several times, despite very polite warnings from the crew that the fuel was running low. He asked for fuel reports and got them. The crew's warnings about fuel were delivered calmly and usually acknowledged. The captain finally agreed to begin the approach 48 minutes after entering the holding pattern, with only 3,000 lbs of fuel indicated on the gauges.

— James Albright

Updated:

2016-08-03

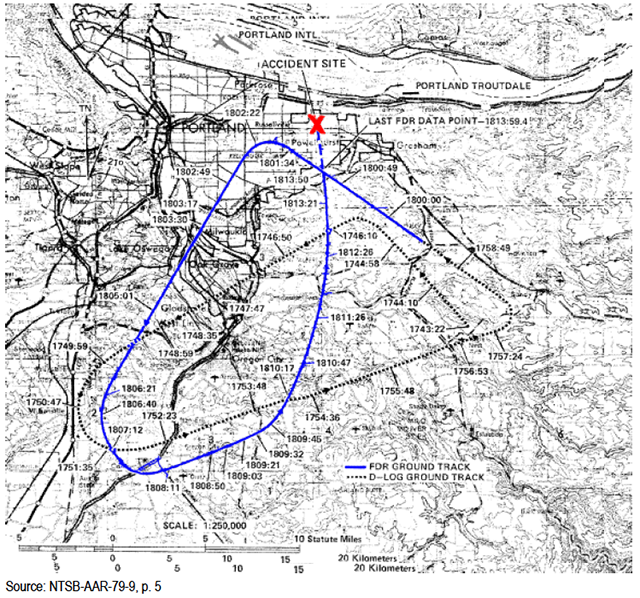

Flight track,

NTSB Report, Figure 1

Once on final approach they started flaming out engines. The airplane impacted six miles southeast of the airport. There was no fire on impact and the airplane was evacuated in 2 minutes. Eight passengers died along with a flight attendant and the flight engineer. The gear was found to be fully extended and locked.

The NTSB blamed the captain for not paying enough attention to the fuel and the flight crew for not communicating their concerns adequately to the captain. United Airlines instituted the industry's first Crew Resource Management program a little more than a year later in 1980. Six years later I was trained by United Airline to fly the Boeing 747 for the United States Air Force. Their CRM course was a mandatory part of their 747's Captain's course. It has changed everything about the way I fly.

1

Accident report

- Date: 28 DEC 1978

- Time: 18:15

- Type: McDonnell Douglas DC-8-61

- Operator: United Airlines

- Registration: N8082U

- Fatalities: 2 of 8 crew, 10 of 189 passengers

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airport: (Departure) Denver-Stapleton International Airport, CO (DEN/KDEN), United States of America

- Airport: (Destination) Portland International Airport, OR (PDX/KPDX), United States of America

2

Narrative

- Flight 173 departed from Denver about 1447 [ . . . ] cleared to Portland on an instrument flight rules (IFR) flight plan. The planned time en route was 2 hrs 26 min. The planned arrival time at Portland was 1713.

- According to the automatic flight plan and monitoring system the total amount of fuel required for the flight to Portland was 31,900 lbs. There was 46,700 lbs of fuel on board the aircraft when it departed the gate at Denver. This fuel included the Federal Aviation Regulation requirement for fuel to destination plus 45 min and the company contingency fuel of about 20 min. During a postaccident interview, the captain stated that he was very close to his predicted fuel for the entire flight to Portland "... or there would have been some discussion of it.” The captain also explained that his flight from Denver to Portland was normal.

- During [the] post accident interview, the captain stated that, when Flight 173 was descending through about 8,000 ft, the first officer, who was flying the aircraft, requested the wing flaps be extended to 15°, then asked that the landing gear be lowered. The captain stated that he complied with both requests. However, he further-stated that, as the landing gear extended, "... it was noticeably unusual and (I) feel it seemed to go down more rapidly. As (it is) my recollection, it was a thump, thump in sound [and] feel. I don’t recall getting the red and transient gear door light. The thump was much out of the ordinary for this airplane. It was noticeably different and we got the nose gear green light but no other lights.” The captain also said the first officer remarked that the aircraft “yawed to the right..." Flight attendant and passenger statements also indicate that there was a loud noise and a severe jolt when the landing gear was lowered.

- At 1712:20, Portland Approach requested, “United one seven three heavy, contact the tower (Portland), one one eight point seven.” The flight responded, “negative, [we'll] stay with you. [We'll] stay at five. [We'll] maintain about a hundred and seventy knots. We got a gear problem. [We'll] let you know.” This was the first indication to anyone on the ground that Flight 173 had a problem.

- For the next 23 min, while Portland Approach was vectoring the aircraft in a holding pattern south and east of the airport, the flightcrew discussed and accomplished all of the emergency and precautionary actions available to them to assure the locked in the full down position. The second officer checked the visual indicators on top of both wings, which extend above the wing surface when the landing gear is down-and-locked.

- The captain stated that during this same time period, the first flight attendant came forward and he discussed the situation with her. He told her that after they ran a few more checks, he would let her know what he intended to do.

- About 1738, Flight 173 contacted the United Airlines Systems Line Maintenance Control Center in San Francisco, California, through Aeronautical Radio, Inc. According to recordings, at 1740:47 the captain explained to company dispatch and maintenance personnel the landing gear problem and what the flightcrew had done to assure that the landing gear was fully extended. He reported about 7,000 lbs of fuel on board and stated his intention to hold for another 15 or 20 minutes. He stated that he was going to have the flight attendants prepare the passengers for emergency evacuation.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

Contacting the company about a maintenance malfunction is one of those steps in the 14 CFR 121 world that cuts two ways: it is a distraction but it does avail the crew of a much deeper bench of experience and knowledge. But with a three person flightcrew, this step could have been accomplished earlier.

- At 1744:03, United San Francisco asked, “okay, United one seventy three . . . You estimate that you’ll make a landing about five minutes past the hour. Is that okay?” The captain responded, “Ya, that’s good ball park. I’m not gonna hurry the girls. We got about a hundred sixty five people on board and we . . . want to . . . take our time and get everybody ready and then we’ll go. It’s clear as a bell and no problem.”

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

While there were a lot of obvious warning signs being ignored so far this one is worth noting. In a four engine airplane each fuel flow meter can be thought of as a "15 minute consumption check." That is, whatever fuel flow you see on one of the four fuel flow meters indicates how much gas the airplane will consume in 15 minutes. Each of their engines was probably indicating around 7,000 PPH at this point and that's all the gas they had. So assuming the gauges were completely accurate, they didn't have enough gas to fly from 1744 to "about five minutes past the hour."

- At 1746:52, the first officer asked the flight engineer, “How much fuel we got . . . ?” The flight engineer responded, “Five thousand.” The first officer acknowledged the response.

- At 1748:54, the first officer asked the captain, “. . .what’s the fuel show now . . . ?" The captain replied, “Five.” The first officer repeated, “Five.” At 1749, after a partially unintelligible comment by the flight engineer concerning fuel pump lights, the captain stated, “That’s about right, the feed pumps are starting to blink.” According lo data received from the manufacturer, the total usable fuel remaining when the inboard feed pump lights illuminate is 5,000 Ibs. At this time, according to flight data recorder (FDR) and air traffic control data, the aircraft was about 13 nmi south of the airport on a west southwesterly heading.

- About 1750:20, the captain asked the flight engineer to “Give us a current card on weight. Figure about another fifteen minutes.” The first officer responded, “Fifteen minutes?” To which the captain replied, “Yeah, give us three or four thousand pounds on top of zero fuel weight.” The flight engineer then said, “Not enough. Fifteen minutes is gonna- really run us low on fuel here.” At 1750:47, the flight engineer gave the following information for the landing data card: “...Okay. Take three thousands pounds, two hundred and four.” At this time the aircraft was about 18 nmi south of the airport in a turn to the northeast.

- At 1751:35, the captain instructed the flight engineer to contact the company representative at Portland and apprise him of the situation and tell him that Flight 173 would land with about 4,000 lbs of fuel. From 1752:17 until about 1753:30, the flight engineer talked to Portland and discussed the aircraft’s fuel state, the number of persons on board the aircraft, and the emergency landing preparations at the airport. At 1753:30, because of an inquiry from the company representative at Portland, the flight engineer told the captain, “He wants to know if we’ll be landing about five after.” The captain replied, "Yes." The flight engineer relayed the captain’s reply to the company representative. At this time the aircraft was about 17 nmi south of the airport heading northeast.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

This was an unnecessary call that (1) may have preoccupied the flight engineer and (2) should have alerted ground personnel that the flightcrew was ignoring a critical fuel state.

- At 1755:04, the flight engineer reported the “...approach descent check is complete.” At 1756:53, the first officer asked, “How much fuel you got now?” The flight engineer responded that 3,000 lbs remained, 1,000 lbs in each tank.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

According to the company's maintenance manual, these gauges were accurate ± 400 pounds, but it is unknown if the crew had this knowledge. They should have been alarmed, however, because it is doubtful any of them had seen so little fuel on a DC-8 before. Had the first officer or flight engineer had this revelation and at this point brought the captain's focus back to where it needed to be, they might have made it back to the runway.

- At 1757:21, the captain sent the flight engineer to the cabin to “...kinda see how things are going. . . .” From 1757:30 until 1800:50, the captain and the first officer engaged in a conversation which included discussions of giving..the flight attendants ample time to prepare for the emergency, cockpit procedures in the event of an evacuation after landing, whether the brakes would have antiskid protection after landing, and the procedures the captain would be using during the approach and landing.

- At 1801:34, the flight engineer returned to the cockpit and reported that the cabin would be ready in “another two or three minutes.” The aircraft was about 5 nmi southeast of the airport turning to a southwesterly heading. Until about 1802:10, the captain and the flight engineer discussed the passengers and their attitudes toward the emergency.

- At 1802:22, the flight engineer advised, "We got about three on the fuel and that's it."

- At 1803:14 Portland Approach asked that Flight 173 advise them when the approach would begin. The captain responded, ". . . They’ve about finished in the cabin. I’d guess about another three, four, five minutes.” At this time the aircraft was about 8 nmi south of the airport on a southwesterly heading.

- At 1806:19, the first flight attendant entered the cockpit. The captain asked, “How you doing?” She responded, “Well, I think we’re ready.” At this time the aircraft was about 17 nmi south of the airport on a southwesterly heading. The conversation between the first flight attendant and the captain continued until about 1806:40 when the captain said, “Okay. We’re going to go in now. We should be landing in about five minutes.” Almost simultaneous with this comment, the first officer said, “I think you just lost number four . . . ,” followed immediately by advice to the flight engineer, “. . . better get some crossfeeds open there or something.”

- At 1806:46, the first officer told the captain, “We’re going to lose an engine. . . ." The captain replied, “Why?” At 1806:49, the first officer again stated, “We’re losing an engine.” Again the captain asked, "Why?" The first officer responded, “Fuel.”

- At 1807:12, the captain called Portland Approach and requested, ". . . would like clearance for an approach into two eight left, now.” The aircraft was about 19 nmi south southwest of the airport and-turning left. This was the first request for an approach clearance from Flight 173 since the landing gear problem began. Portland Approach immediately gave the flight vectors for a visual approach to runway 28L. The flight turned toward the vector heading of 010°.

- From 1807:27 until 1809:16, the following intracockpit conversation took place:

- 1807:27 - Flight Engineer: “We’re going to lose number three in a minute, too.”

- 1807:31 - Flight Engineer: “It’s showing zero.”

Captain: “You got a thousand pounds. You got to.”

Flight Engineer: “Five thousand in there . . .but we lost it.”

Captain: “Alright.” - 1807:38 - Flight Engineer: “Are you getting it back?”

- 1807:40 - First Officer: “No number four. You got that crossfeed open?”

- 1807:41 - Flight Engineer: “No, I haven’t got it open. Which one?”

- 1807:42 - Captain: “Open ‘em both--get some fuel in there. Got some fuel pressure?”

Flight Engineer: “Yes, sir.” - 1807:48 - Captain: “Rotation. Now she’s coming.”

- 1807:52 - Captain: “Okay, watch one and two. We’re showing down to zero or a thousand.”

Flight Engineer: “Yeah”

Captain: “On number one?”

Flight Engineer: “Right.” - 1808:08 - First Officer: “Still not getting it.”

- 1808:11 - Captain: “Well, open all four crossfeeds.”

Flight Engineer: “All four?”

Captain: “Yeah.” - 1808:14 - First Officer: “Alright, now it’s coming.”

- 1808:19 - First Officer: “It’s going to be--on approach though.”

Unknown Voice: “Yeah.” - 1808:42 - Captain: “You gotta keep ‘em running. . . .”

Flight Engineer: “Yes, sir.” - 1808:45 - First Officer: “Get this. . .on the ground.”

Flight Engineer: “Yeah. It’s showing not very much more fuel.” - 1809:16 - Flight Engineer: “We’re down to one on the totalizer. Number two is empty.”

- At 1809:21, the captain advised Portland Approach, “United, seven three is going to turn toward the airport and come on in.” After confirming Flight 173’s intentions, Portland Approach cleared the flight for the visual approach to runway 28L.

- At 1810:17, the captain requested that the flight engineer “reset that circuit breaker momentarily. See if we get gear lights.” The flight engineer complied with the request.

- At 1810:47, the captain requested the flight’s distance from the airport. Portland approach responded, “I’d calI it eighteen flying miles.” At 1812:42, the captain made another request for distance. Portland Approach responded, “Twelve flying miles.” The flight was then cleared to contact Portland tower.

- At 1813:21, the flight engineer stated, “We’ve lost two engines, guys.” At 1813:25, he stated, “We just lost two engines - one and two.”

- At 1813:38, the captain said, “They’re all going. We can’t make Troutdale.” The first officer said, “We can’t make anything.”

- At 1813:46, the captain told the first officer, “Okay. Declare a mayday.” At 1813:50, the first officer called Portland International Airport tower and declared, “Portland tower, United one seventy three heavy, Mayday. We’re--the engines are flaming out. We’re going down. We’re not going to be able to make the airport.” This was the last radio transmission from Flight 173.

- About 1815, the aircraft crashed into a wooded section of a populated area of suburban Portland about 6 nmi east southeast of the airport. There was no fire. The wreckage path was about 1,554 ft long and about 130 ft wide.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

3

Analysis

- Throughout the landing delay, flight 173 remained at 5,000 ft with landing gear down and flaps set at 15°. Under these conditions, the Safety Board estimated that the flight would have been burning fuel at the rate of about 13,209 lbs per hour--220 lbs per min. At the beginning of the landing delay, there were about 13,332 lbs of fuel on board.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.1

- Upon request, United Airlines provided the Safety Board with an error analysis of the fuel quantity indicating system for the accident aircraft. Analyses were prepared for three different assumptions The first analysis assumed that all errors were at their limits and in the same direction. The second analysis assumed that all errors were at their limits but were distributed randomly with respect to sign (rootsum-square analysis). The third analysis was a probable error analysis. All errors in this analysis were those associated with empty or near empty tanks.

- These analyses indicated the following:

| Sum of Indicators | Totalizer | |||

| Analysis Method | High Error | Low Error | High Error | Low Error |

| Worst-Case Error (lbs) | 2,283 High | 1,482 Low | 3,961 High | 3,606 Low |

| Root-Square-Sum Error (lbs) | 828 High | 28 Low | 1,312 High | 957 Low |

| Probable Error (lbs) | 685 High | 185 Low | 1,239 High | 885 Low |

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.16

- Excerpt from United Airlines Flight Operations Manual, paragraph 6.2, June 30, 1978: “Except as otherwise specifically directed by the captain, all crew members noting a departure from prescribed procedures and safe practices should immediately advise the captain so that he is aware of and understands the particular situation and may take appropriate action.”

- Excerpts From United Airlines DC-8 Flight Manual Landing Gear Lever Down and Gear Unsafe Light On: "If the visual down-lock indicators indicate the gear is down then a landing can be made at the captain’s discretion.” (Dated January 1, 1974, pg. I-44.)"

- Excerpts From United Airlines Maintenance/Overhaul manual “Fuel Quantity Indicator System - Tolerance:

- All tanks at empty, + 150 pounds.

- Tank at full

#1 & #4 Main + 400 pounds

#1 & #4 Alt ± 225 pounds

#2 & #3 Main ± 400 pounds

#2 & #3 Alt ± 250 pounds”

(Dated January 19, 1976, page 201.)

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶1.17

- The first problem which faced the captain of Flight 173 was the unsafe landing gear indication during the initial approach to Portland international Airport. This unsafe indication followed a loud thump, an abnormal vibration, and an abnormal aircraft yaw as the landing gear was lowered. The Safety Board’s investigation revealed that the landing gear problem was caused by severe corrosion in the mating threads where the right main landing gear retract cylinder assembly actuator piston rod was connected to the rod end. The corrosion allowed the two parts to pull apart and the right main landing gear to free fall when the flightcrew lowered the landing gear. This rapid fall disabled the microswitch for the right main landing gear which completes an electrical circuit to the gear position indicators in the cockpit. The difference between the time it took for the right main landing gear to free fall and the time it took for the the left main landing gear to extend normally, probably created a difference in aerodynamic drag for a short time. This difference in drag produced a transient yaw as the landing gear dropped.

- Although the landing gear malfunction precipitated a series of events which culminated in the accident, the established company procedures for dealing with landing gear system failure(s) on the DC-8-61 are adequate to permit the safest possible operation and landing of the aircraft. Training procedures, including ground school, flight training, and proficiency and recurrent training, direct the flightcrew to the Irregular Procedures section of the DC-8 Flight Manual, which must be in the possession of crewmembers while in flight. The Irregular Procedures section instructed the crew to determine the position of both the main and nose landing gear visual indicators. “If the visual indicators indicate the gear is down, then a landing can be made at the captain’s discretion.” The flight engineer’s check of the visual indicators for both main landing gear showed that they were down and locked.

- From the time the captain informed Portland Approach of the gear problem until contact with company dispatch and line maintenance, about 28 min had elapsed. The irregular gear check procedures contained in their manual were brief, the weather was good, the area was void of heavy traffic, and there were no additional problems experienced by the flight that would have delayed-the captain’s communicating with the company. The company maintenance staff verified that everything possible had been done to assure the integrity of the landing gear. Therefore, upon termination of communications with company dispatch and maintenance personnel, which was about 30 minutes before the crash, the captain could have made a landing attempt. The Safety Board believes that Flight 173 could have landed safely within 30 or 40 min after the landing gear malfunction.

- [ . . . ] the crew should have known and should have been concerned that fuel could become critical after holding. Proper crew management includes constant awareness of fuel remaining as it relates to time. In fact, the Safety Board believes that proper planning would provide for enough fuel on landing for a go-around should it become necessary. Such planning should also consider possible fuel-quantity indication inaccuracies.

- On the contrary, the cockpit conversation indicates insufficient attention and a lack of awareness on the part of the captain about the aircraft's fuel state after entering and even after a prolonged period of holding. The other two flight crewmembers, although they made several comments regarding the aircraft's fuel state, did not express direct concern regarding the amount of time remaining to total fuel exhaustion.

- The Safety Board believes that this accident exemplifies a recurring problem--a breakdown in cockpit management and teamwork during a situation involving malfunctions of aircraft systems in flight. To combat this problem, responsibilities must be divided among members of the flightcrew while a malfunction is being resolved. In this case, apparently no one was specifically delegated the responsibility of monitoring fuel state.

4

Cause

- The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable cause of the accident was the failure of the captain to monitor properly the aircraft’s fuel state and to properly respond to the low fuel state and the crewmember’s advisories regarding fuel state. This resulted in fuel exhaustion to all engine‘s. His inattention resulted from preoccupation with a landing gear malfunction and preparations for a possible landing emergency.

- Contributing to the accident was the failure of the other two flight crewmembers either to fully comprehend the criticality of the fuel state or to successfully communicate their concern to the captain.

Source: NTSB AAR-79-7, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-79-7, United Airlines, Inc., McDonnell-Douglas, DC-8-61, N8082U, Portland, Oregon, December 28, 1978