One hundred years ago the effort to fly where no one has flown before, set speed and altitude records, and take risks that were more likely to fail than succeed was pretty much the way things were. If you wanted to expand the horizons of aviation, that's what you did. This is the story of one such effort, the attempt to link London and Cape Town.

— James Albright

Updated:

2020-02-20

100 years later

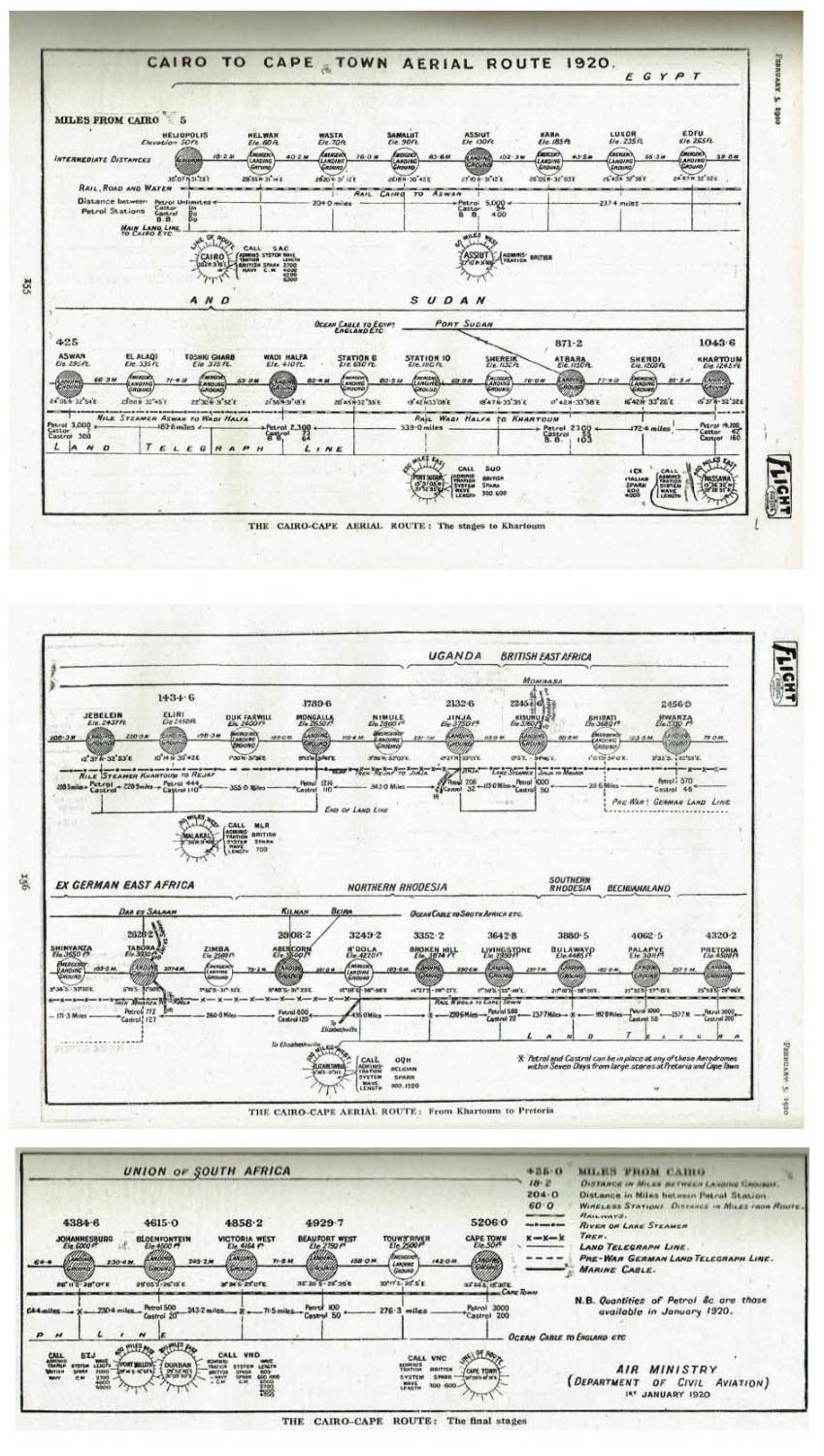

Cairo to Cape Town

Aerial Route 1920, Barraclough, pp. 10-11

I write about this only to discuss that such risks might be necessary at times to expand our horizons or rally the national spirit. The Royal Air Force had a vested interest in this particular record as a way of exercising national power. But that was then and this, as they say, is now. These days the lure of setting records are a bit silly. See Record Setting Intentional Noncompliance for an example. These days, a more methodical approach is called for. With the increased speed and mass of airplanes the probability of walking away from a crash are diminished. As population density worldwide has increased dramatically in the last 100 years, the chances of collateral damage are also increased.

Having said all that, this is part of our history as aviators. It is history worth knowing. (So we can better detect similar efforts in the future.)

Major General W. G. Salmond, KCMG, CB, DSO, Commanding Officer of the Royal Air Force in the Middle East, was a visionary. He and Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, GBE, KCB, CMG, who had the title of Controller General of Civil Aviation, dreamt of Cairo being the hub of the British Empire's air routes, as it already was for the Empire's sea routes which transited the Suez Canal on their way to India, the Far East, Australia and New Zealand, and down the east coast of Africa to Cape Town. . . . Barely three months after the end of the war, Salmond organised three survey parties to create the necessary string of landing grounds. The first party, under Major Long, DSO, was to create the airfields from Cairo to Lake Victoria. The second party, under Major Emmett, was to cover the sector from Lake Victoria to the southern end of Lake Tanganyika, while the third party under Major Court-Treatt, was to be responsible for the remainder of the route to Cape Town. The brief given to these officers was that there must be airfields stocked with fuel not more than 400 miles apart and interspersed with emergency landing grounds every 120 miles.

Source: Barraclough, p. 6

Major General Sykes wrote about the new Imperial air routes: "If an Empire air power, both service and civil, is developed, organised and co-ordinated, our supremacy in the air may in the future be more valuable in assisting to maintain the peace of the world than our supremacy on the sea has been in the past. The Empire is geographically in an unequalled position for establishing air depots, re-fuelling bases and meteorological and wireless stations in every part of the world. Egypt must be the 'hub' of the Indian, Australian and Cape routes and the heart of the whole system." . . . "We have seen the great value of the aeroplane in war; the next war will in all probability open with a fight for the mastery of the air."

Source: Barraclough, p. 9

In the House of Commons, Winston Churchill, one of the greatest proponents of aviation during the First World War, voiced the hope that someone would encourage the opening of the air route to the Cape by offering a reward for the first successful flight. The response was not long in coming. While the aircraft constructors were struggling with the post-war recession it was the megalomaniac Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Daily Mail and The Times, who offered a purse of £10,000 (£427,000) to be awarded to the owners and crew of the aeroplane that made the first successful flight from Cairo to the Cape.

Source: Barraclough, p. 15

1 — Captains S. Cockrell and F.C. Broome, DFC

2 — Major H. G. Brackley, DSO, DSC and Captain F. Tyrnms, MC

3 — Lieutenant Colonel Pierre van Rynevald, DSO, MC and Captain Quintin Brand, DSO, MC, DFC

1

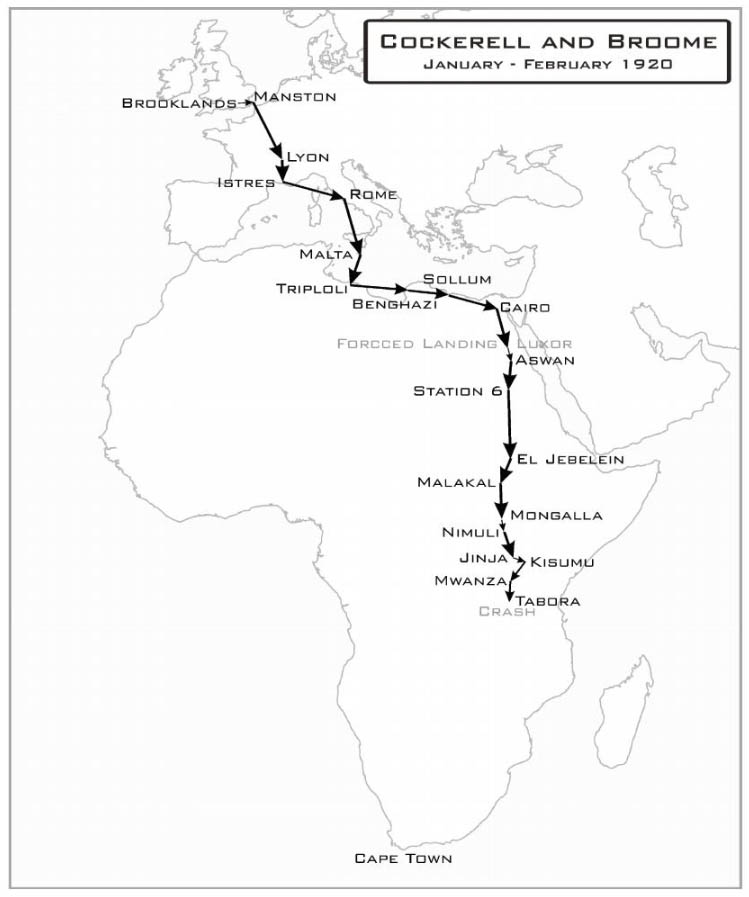

Captains S. Cockrell and F.C. Broome, DFC

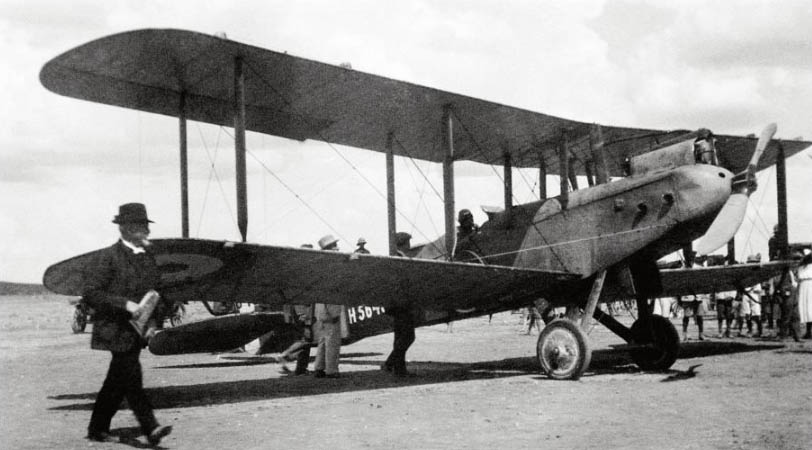

The Vickers-Vimy-Rolls commercial machine charted by The Times, Barraclough, p. 17

- Date: 29 February 1920

- Type: Vickers Vimy Commercial

- Pilots: Captains S. Cockrell and F.C. Broome, DFC

- Registration: G-EAAV

- Airport: (Departure) Brooklands

- Airport: (Destination) Cape Town

- Crashed at Tabora, Tanganyika [today: Tanzania]

- Chosen to fly the aircraft were two pilots who had given a good account of themselves in the war and were now Vickers test pilots. Senior pilot was Captain Stanley Cockerell, born in London, who had joined the RFC as a dispatch rider the day after war was declared; he had become an air mechanic and then a sergeant-pilot. He was commissioned after destroying three Fokkers while flying a DH2 and was then wounded in November 1916, the bullet remaining in his hip. He survived the war with a total of seven enemy aircraft destroyed and became Vickers chief test pilot.

- Second pilot was Captain Frank "Tommy" Broome, DFC, who was born in London in 1892 and educated at Uppingham. He then spent three years working on cattle ranches in Australia before returning to England in 1914 and joining the Middlesex Regiment. Following his commission into the RASC, he transferred to the RFC in 1917 and was posted to 151 Squadron in France where he was in Cockerell's flight. He was awarded the DFC after destroying three German aircraft in one week. He, too, joined Vickers as a test pilot after the war and together with Cockerell had made the first flight of the Vimy Commercial on 13th April 1919. The pair were known as the "Heavenly Twins."

Source: Barraclough, p. 18

The Vimy took off from Brooklands on January 24, 1920 and flew to Ystres, France. Over the next week they stopped in Rome, Malta, Tripoli, and then to Cairo. On February 6th they had to make a precautionary landing near Luxor for a water jacket leak, and then they flew on to Assouan. The next day they made two more forced landings but made it to Khartoum on February 8th.

- By the time the Vimy reached Mongalla however her airframe and engines were in serious need of overhaul and this took five days of steady work. When they eventually took off on 20th February a magneto cut on the starboard engine, resulting in a difficult forced landing for Cockerell and Broome back at Mongalla. The defective magneto replaced, they made a further start and were reported over Rejaf on their way to Jinja in the Protectorate of Uganda.

Source: Barraclough, p. 21

- With the engines running fairly well and with a lighter load the Vimy took off at 06:40 on 26th February for Tabora in Tanganyika, formerly German East Africa, a distance of 366 miles, the route taking them down the eastern shores of Lake Victoria to Mwanza. After an overnight stay at Tabora they were once again airborne at 06:50 on the 27th, but water leaking from an engine caused them to return and land again for yet more repairs. These effected, they took off at 14:00 but just as they reached flying speed the starboard engine failed and the aeroplane crashed on the scrub just off the end of the runway, collided with an anthill and came to rest on its nose, both undercarriages being forced through the lower planes and fuel tanks, fortunately without catching fire. Save for Cockerell spraining his wrist and Wyatt bruising a leg, there were, amazingly, no injuries. Situated high between the wings neither engines nor propellers were damaged and arrangements were later made to remove and store them before the crew headed for Dar es Salaam and England - by sea.

- For their efforts both Cockerell and Broome were awarded the Air Force Cross. Both pilots went back to test flying for Vickers, Cockerel being killed during a German bombing raid in 1940 and Broome dying in 1948.

Source: Barraclough, p. 22

Cockerell and Broome route, Barraclough, p. 23

2

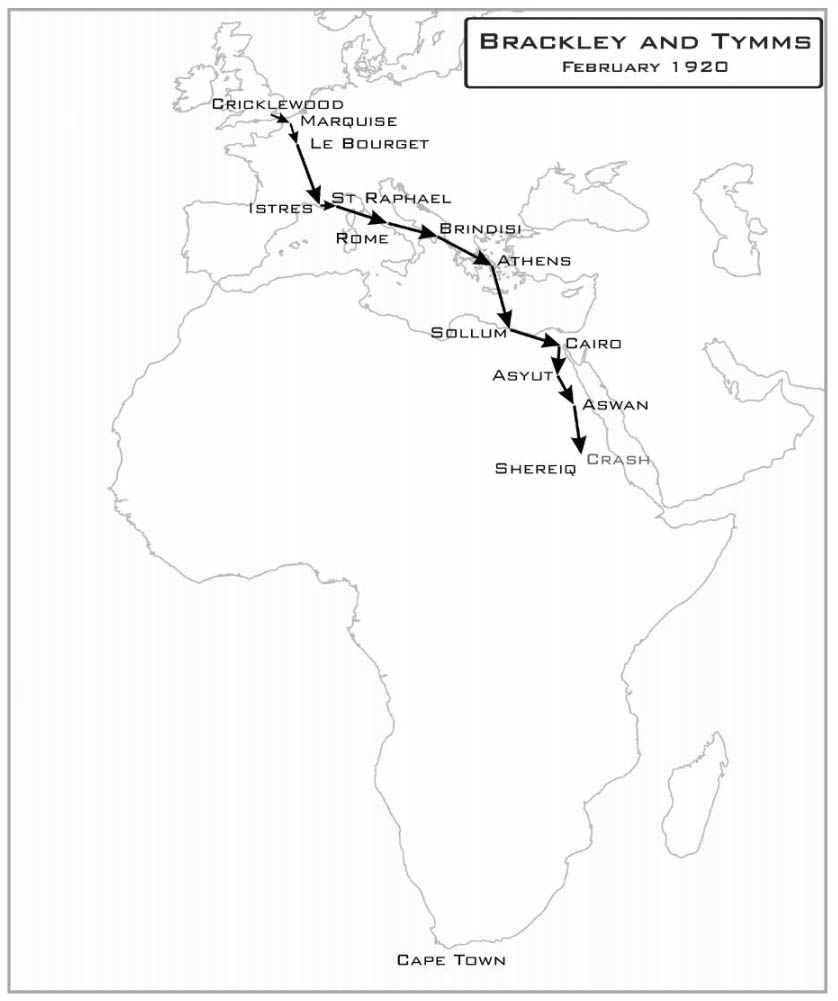

Major H. G. Brackley, DSO, DSC and Captain F. Tyrnms, MC

Brackley's Handley Page O/40 crashed at El Shereik, Sudan, Barraclough, p. 27

- Date: 25 February 1920

- Type: Handley Page 0/400, G-EAMC, 2x350 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs

- Pilots: Major H. G. Brackley, DSO, DSC and Captain F. Tyrnms, MC

- Registration: G-EAMC

- Airport: (Departure) Cricklewood

- Airport: (Destination) Cape Town

- Forced landing and wrecked at Shereik, Sudan

- Herbert George Brackley was born on 4th October 1894 and, after a typical middle-class English upbringing, he joined the Royal Naval Air Service in 1915 and learned to fly with No.4 Wing, RNAS Eastchurch. He was then posted to France where he flew bombers with distinction and ended the war with the DSO and DSC. Determined to pursue a career in civil aviation, he pioneered the civil flying of the Handley Page bombers in which he had achieved such success during the recent war.

- At 08:30 on 25th January, a typically misty January morning, Brackley and his crew took off from Cricklewood aerodrome for Paris's Le Bourget airfield, hoping to make Lyon by the end of the day.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 25 - 27

The weather forced them to land short but they made it the next day. Winds were such that at times their groundspeed was only 40 mph. They made it to Istres the following day and then to Rome. Leaving Rome they had to turn back due to weather and landed at a nearby Naval Air Station.

- It was at Brindisi that disaster struck. Taxiing out to take off on the morning of 1st February the starboard wheel of the O/400 sank into boggy ground at the far end of the aerodrome. Without waiting for the engines to be shut down, Knight [engineer] and Stoten [rigger] jumped down from the aeroplane with spades and started to dig the wheel out. Stoten stepped back suddenly and the starboard propeller struck his head, fracturing it badly in several places and leaving the propeller with two broken blades; Stolen died on the way to hospital. Tymms was deputed to escort Stoten's body from the aerodrome to the town and, hearing that Captain Shakespeare, the Handley Page representative in Athens, had an O/400 there, Brackley sent him on to Athens by ship to collect one of the propellers, Tymms leaving Brindisi that night in the SS Semiramis. Selecting the only serviceable propeller out of the four that were in Athens, Tymms had to wait over a week before he could set sail on the SS Mikali back to Brindisi. He finally arrived back in Brindisi on 11th February only to find that inadequate packing and water in the hold of the ship had so damaged the propeller that it was totally unserviceable. Meanwhile Brackley, having attended Stoten's funeral on February 3rd, then left immediately for Taranto to try to find a propeller there, but it transpired that there were absolutely no spares whatsoever throughout Italy.

- There was nothing else they could do but wait for a replacement propeller to be sent from England. This arrived by sea on the 17th February in the care of Banthorpe who was Stoten's replacement and who escorted the propeller all the way from London.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 25 - 27

On the 18th they left for Athens, the day after that Sollum, then on to Heliopolis and Cairo. The next few days saw more forced landings and stops in Assint (due to a misread of the map along the Nile) and Assyut.

- They took off for Wadi Halfa at 10:40 on 24th February. Now their troubles really began. Soon after take-off the port fuel system gave more trouble, requiring Knight's constant attention. Then, for the first time, they encountered the hot arid conditions of desert flying. Cruising at 6,000 feet without coats was at first a pleasant change to earlier winter conditions, but soon they found that the south-westerly wind was bringing in hot air from the desert and flying conditions became very bumpy with the aircraft losing height rapidly despite application of power. By noon they were losing height even with the engines running at full power and Brackley decided to land at Assouan (Aswan) in order to save his engines and thereafter only fly early in the morning. Their delay was made tolerable by the luxurious conditions of the Cataract Hotel, only spoilt by having to get up at 03:30 next morning, not just to start flying early, but because the only method of transport at that time of day involved an hour's ride to the landing ground on a donkey while Major Turner followed later with the baggage on a light railway engine. This early start was necessary so that they could get airborne in the colder air of the early morning, the aerodrome being surrounded by black rocky hills over which the heavily-laden O/400 would probably have failed to climb later in the day.

- Tymm' s account of this last flight graphically describes the end of their adventure:

- Thus ended Handley-Pages', the Daily Telegraph's and Brackley's flight, but it carried a tragic sequel to it. After the engines were salvaged with the help of the Sudan Railways the Royal Air Force offered Brackley a Khartoum-based 0/400 with which to complete his journey. The aeroplane had lain three months in the open and Brackley decided it was unfit to fly, so declined the offer. The RAF then decided to fly it back to Cairo themselves but two hundred miles north of Khartoum the aeroplane broke up in mid-air and the entire crew was killed.

- Brackley himself went on to make a distinguished career in civil aviation, flying for Handley Page, Imperial Airways and BOAC, and planning many of the Imperial routes. He rose to the rank of Air Commodore during WWII and later was CEO of British South American Airways. Tragically he was drowned when swimming in Rio de Janeiro in 1948 at the age of 54.

Progress was good with a ground speed of 65 mph, steadily improving to over 90 as we climbed into a more northerly wind. At 6,000 feet, after climbing for an hour, we seemed to be at our ceiling. Engines were running full out, but the air was cooler and after another half hour we were at 7,000 feet. Then, with engines still running flat out, we lost height. Brackley's aim was to gain as much height as possible before the heat of the day in the hope of maintaining it with the reduced load of the aircraft. Conditions improved. We reached 7,800 feet and maintained it. Ground speed increased to 90 mph and all looked fair for our goal (Khartoum), 1,200 miles from Cairo. We began to plan our next flight to start before dawn in the hope of beating the bogey of the route - low density heated air. Our course lay along the Nile to Korosko - where is the most fascinating desert of black rocks set in golden brown sand - thence across the desert to Station 4 on Kitchener's railway from Wadi Haifa to Abu Hamed - the railway a thin pencil line on a flat featureless desert; and eventually following the Nile again via Atbara to Khartoum. We reached Abu Hamed after four hours' flying.

Twenty minutes later fate ordained the end of the flight. A violent oscillation and vibration of the machine set in, which seemed to threaten a break-up; the biplane tail twisted and rocked in the most alarming manner. Later we recognised the symptoms as tail flutter, but the knowledge would not have been much comfort to us then. No one expected the airframe to last more than a minute. Two of the crew had to hold down a large box of spares and tools which was screwed down on the rear gunner's compartment, and which came adrift. Brackley shut down the engines and put the machine into a slow straight glide. There followed the longest quarter of an hour any of us had experienced, and none wished to repeat. The rudders were jammed by the oscillating elevators. At 2,000 feet we began to think it worth while to look for a forced landing place. We were over the railway and the river and Brackley selected a suitable looking area ahead. He had only partial control by using ailerons and was unable to complete his turn into wind. The north wind which had generously helped our ground speed, now proved too strong for our undercarriage, and G-EAMC ploughed her nose into the desert sand. Most of the crew were thrown clear. Brackley was somewhat shaken - no one else was hurt. So, on 25th February the attempt failed 6 miles north of El Shereik, Sudan some two hundred miles north of Khartoum.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 25 - 27

Brackley and Tymms route, Barraclough, p. 30

3

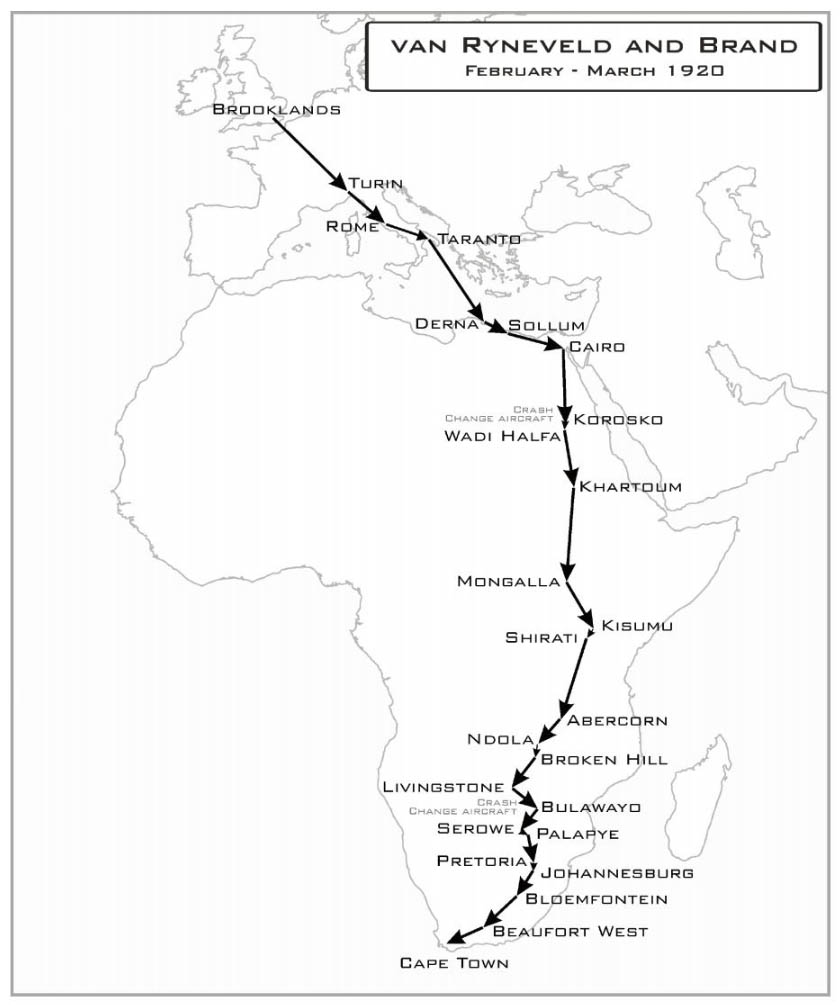

Lieutenant Colonel Pierre van Rynevald, DSO, MC and Captain Quintin Brand, DSO, MC, DFC

Matching the enterprise of Lord Northcliffe was the patriotism of Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, by then President of the Union of South Africa. Smuts was a strong supporter of air power and he was determined that South African pilots should have the honour of conquering the new Imperial route. To this end he ordered, at a cost of £4,500 (£192,000), the purchase by the South African Government of a second Vickers Vimy, registered G-UABA and christened Silver Queen, but still in the configuration of the World War I bomber.

Pilots: Lieutenant Colonel Pierre van Rynevald, DSO, MC and Captain Quintin Brand, DSO, MC, DFC

Source: Barraclough, pp. 15 - 16

Aircraft 1

The crash of Silver Queen at Korosko, Barraclough, p. 35

- Date: 11 February 1920

- Type: Vickers Vimy, G-UABA, Silver Queen, 2x350 hp Rolls Royce Eagle Vllls

- Registration: G-UABA

- Airport: (Departure) Brooklands

- Airport: (Destination) Youngsfield

- Result: Forced landing at Korosko, aircraft destroyed

- The Vickers Vimy IV bomber that Smuts ordered for the South African entry was still in front-line service with the Royal Air Force. It had already proved its worth in long distance flying by being the first aircraft to fly the Atlantic and to make the long voyage from England to Australia. To fly the machine Smuts selected a highly-decorated South African pilot still serving in the Royal Air Force, 28-year-old Lieutenant-Colonel Hesperus Andrias "Pierre" van Ryneveld, DSO, MC. Van Ryneveld chose as his co-pilot 26-year-old Captain Christopher Joseph Quintin "Flossie" Brand, DSO, MC, DFC. Smuts had already chosen van Ryneveld to head up the new South African Air Force which was to come into being on 1st February 1920. So what better way for the young airman to return to South Africa than by making the very first flight, not just from Cairo, but all the way from England.

- With Van Ryneveld and Brand at the controls and Rolls Royce mechanics Sheratt and Burton in the cabin, Silver Queen left Brooklands at 07:30 on 4th February 1920, heading directly for Turin in Northern Italy. After climbing through the overcast of the English Channel they then flew for four hours in thick cloud and, being unsure of their position, landed on the race course of Mellisant in central France to check their whereabouts. They were only 15 minutes on the ground before they took off again and crossed the Alps at 12,500 feet, close to Mont Blanc, landing in Turin 8 hours and 50 minutes after leaving Brooklands - a cracking start. But engine trouble had already started and both pilots and mechanics stayed up all night repairing a leak in the radiator of the port engine, the repairs taking until mid-morning. They eventually took off at 11:30 for Rome. Arriving overhead the capital van Ryneveld decided to carry on to Foggia, but an hour later he was back landing at Rome's Centocello airfield, having encountered strong headwinds which would have prevented him landing at Foggia before dark.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 31 - 346

From there they made it to Taranto and decided they would cross the Mediterranean at night.

- Half an hour after leaving Italy they ran into headwinds that increased to gale force strength, creating appallingly-bumpy conditions so that by the time they were abeam the Greek island of Zante they were flying into the teeth of a full gale, in pitch blackness and making hardly any headway. After two hours the gale abated sufficiently for them to make progress, but Crete passed by unseen in the cloud and darkness. To add to their discomfort and anxiety the instrument lighting in the open cockpit failed and they had to conduct their navigation by the light of an electric torch. Dogged tiredness soon added to their problems, van Ryneveld keeping himself awake by slapping his face with his gloves while trying to stop Brand falling asleep by repeatedly shining the torch into his eyes. Nor did the mechanics escape the discomfort, sitting in the dark strapped to their seats in the body of the aircraft, bruised and aching from the constant buffeting.

- Handing control from one to the other, at 4 o'clock in the morning the two pilots struggled on; a second storm battered them and they climbed to 9,000 feet, skimming the towering cloud tops, desperately hoping that their course was good but scarcely able to check their heading in the failing light of the torch. Eventually dawn broke; van Ryneveld was to say later that it was the most beautiful dawn they had ever experienced. Having had no landmarks by which to judge the distance they had traveled, and not knowing what their groundspeed was throughout the long night, they descended to 1,000 feet, peering into the gloom for a sight of land, but all they saw for miles around was the heaving sea. On and on they flew, holding their southerly course, becoming desperately worried that their fuel would run out, the minutes crawling by like hours. At last, one and a half hours after dawn had broken they caught their first glimpse of the north African coastline; immediately their spirits rose and they set course for Derna, the most northern airfield on the Libyan coast where they landed at 08:30, eleven hours after leaving Taranto.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 31 - 346

They flew on to Sollum and then to Cairo.

- Their arrival in Cairo was greeted with great excitement in South Africa. Now the race to Cape Town was really on. Cockerell and Broome were well down the Nile at Station 6, some 640 miles - but no more than a day's flying - ahead, while Brackley and Tymms were still stuck in Brindisi awaiting their replacement propeller from England. Wasting no time, and with Burton's place on the Vimy taken by Flight Sergeant Newman, an RAF mechanic, van Ryneveld took the Silver Queen off almost at midnight on the 10th February, intending to make a non-stop flight to Khartoum. With a good tail-wind they made excellent progress down the Nile in the cool night air, reaching Korosko at about 05:00 next morning, having covered the 530 miles at a ground speed of over 100 mph, and with The Times Vimy at Jebelein only 680 miles ahead. Then disaster struck! The temperature on the starboard engine had risen above the danger point of 100 degrees and by the light of their torches the pilots could see that the radiator cock was open and what remained of the water was spurting out of the rapidly overheating engine. There was nothing for it but to make an immediate precautionary landing before the engine seized. In the half-light of dawn van Ryneveld brought the Vimy in to a perfect touch-down on the only open patch of sand among the hills. All seemed well but unseen by the pilots as they rolled forward in the half-light was a heap of boulders directly ahead of them and with a great crash the Vimy smashed into them. None of the crew was hurt but the aircraft was destroyed beyond repair leaving, amazingly, both engines intact.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 31 - 346

Aircraft 2

Crash of the Silver Queen II at Bulaway, Barraclough, p. 36

- Date: 3 March 1920

- Type: Vickers Vimy, F8615, Silver Queen II, 2x350 hp Rolls Royce Eagle Vllls

- Registration: F8615

- Airport: (Departure) Cairo

- Airport: (Destination) Youngsfield

- Result: Crashed on take-off from Bulawayo. aircraft destroyed

- Sensing keen disappointment throughout South Africa, Smuts immediately arranged for the RAF in Cairo to place another Vimy at the disposal of van Ryneveld and Brand, who were undeterred by their crash. The engines (which had been specially modified for the Africa trip), the long range tanks and other special fittings from Silver Queen, were all dismantled from the wreckage, sent to Assouan and railed up to Cairo. There RAF mechanics worked day and night installing them into a standard Vimy which was then named Silver Queen II and was ready to fly by 22nd February, eleven days after the crash at Korosko. At 08:10 on 22nd February, Van Ryneveld and Brand, with Sheratt and Flight Sergeant Newman, took off from Cairo for Khartoum.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 34 - 36

They landed in Wadi Halfa when faced with strong headwinds and then on to Khartoum. They found their cylinder water jackets were leaking and had each replaced with spares provided by the RAF.

- They finally made Mongalla in the mid-afternoon, making their customary low pass over the airfield to check the runway for obstructions. To their horror, when they opened the throttles to go round for a landing the engines failed to respond, only half the cylinders firing in the extreme heat, and they staggered along at tree top height finally collapsing into a heavy landing during which, fortunately, no damage was done, but it was a close call!

Source: Barraclough, pp. 34 - 36

They pressed on a discovered dust devils up to 8,000 feet on their way to Kisimu. The next flight saw more engine problems and a forced landing on the shores of Lake Victoria, 3,680 feet above sea level and the highest landing field they had yet encountered. van Ryneveld decided to discard all non-essential equipment to lighten the aircraft. Their next airport was Abercorn (5,500 feet above sea level) and then on to Ndola with fuel blockage to three cylinders.

- Heavy rains waterlogged the airfield at Ndola, causing a two-day delay, and they only reached Broken Hill on the morning of 2nd March and Livingstone later that afternoon. Hundreds of Africans flocked to the aerodrome to see the "bird-machine" arrive and excitedly helped to extricate Silver Queen II when she became bogged down in the muddy airfield. They helped further by tramping down the grass on the waterlogged runway in order to allow the aeroplane to take off for Bulawayo where she arrived just after midday on 5th March. Now the great Limpopo river and the South African border lay just 170 miles to the south; for the next few days they would be making a triumphant series of flights across their home country to Cape Town. All the South African cities with landing grounds on the remaining route prepared excitedly for their arrival. But fate would have it otherwise ...

- Taking off from Bulawayo racecourse on the morning of Saturday 6th March, a height of 4,485 feet above sea level, Silver Queen II laboured into the thin air and, failing to climb when in the lee of a low line of hills, sank into the bush and was completely wrecked. Suffering only scratches and bruises the crew emerged from the wreckage with their hopes in ruins.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 34 - 36

Aircraft 3

Voortrekker landing at Beaufort West, last stop before Cape Town, Barraclough, p. 37

- Date: 16 March 1920

- Type: de Havilland DH9, H5648, Voortrekker

- Registration: G-UABA

- Airport: (Departure) Bulawayo

- Airport: (Destination) Youngsfield

- Result: First ever flight from England to Cape Town (45 days)

- General Smuts, however, had other ideas. He was still determined that his pilots should achieve the distinction of being the first airmen to have flown from London to Cape Town, so he sent a signal to the disconsolate pilots that another aircraft would be sent from Pretoria to Bulawayo to allow them to finish the course.

- Not wishing to be further delayed, the two South Africans left Bulawayo on 17th March for Pretoria, landing en route at Serowe and Palapye in Bechuanaland to thank Chief Khama and the Bamangwato people for all their work in constructing those aerodromes. They then flew to Pretoria where they received a heroes' welcome and next day to Johannesburg for a similar reception. Finally they flew to van Ryneveld's home town of Bloemfontein and then on to Beaufort West before finally landing at Youngsfield in Wynberg, Cape Town's aerodrome, where they arrived at 1600 on 20th March, to a tumultuous welcome from General Smuts himself, Lord Buxton, the Governor General, and a large gathering of military and civic officials.

- Forty-five days after leaving Brooklands, of which 109 hours and 30 minutes was flying time, Pierre van Rynveld and Quintin Brand had finally reached Cape Town, the first aviators to fly to the Cape from England. Despite this achievement, they were disqualified from collecting Lord Northcliffe's £10,000 purse, as they failed to arrive in the same aeroplane in which they started, leaving two crashed machines on the way. Their courageous flight was rightly hailed as a triumph by the world's popular press and they were each justly rewarded with £2,500 (£71,000 today) by an appreciative South African government. But with a trail of wrecked aircraft strewn down the African continent it was hardly a convincing way of persuading Britain and South Africa that their capitals could now be joined by aerial travel.

Source: Barraclough, pp. 36 - 38

van Ryneveld and Brand route, Barraclough, p. 40

4

Comments and predictions

It’s incredible to think that in less than 25 years from the Race to the Cape the B-29 was produced...25 more years and we’re on the moon!

— Steven Foltz

It’s only been 100 years since those and similar attempts and yet look how far we’ve come. As much as we have advanced in such a short time I can only imagine what the next 100 years in aviation will be like.

— Ivan Luciani

Autoland was in its infancy when I started and the idea of navigating to less that 0.01 nautical miles accuracy would have been laughable. And that was just 42 years ago. I can't begin to hypothesize about the next 100 years but I can take a crack at the next 10. I do think we will be seeing single pilot airliners by then and I rue the day. Last year “Robo Pilot,” a drop in device that held the yoke and throttle as well as pushed the rudder pedals of a Cessna 172, passed its practical test with the FAA watching. Of course it also crashed a few flights later. But no matter, we are getting there. The FAA is also on a verge of approving single pilot cargo flights on very large airplanes. The idea is that if the only pilot on the aircraft is incapacitated, a standby pilot on the ground will guide the airplane to a large runway capable of supporting auto land and will do just that.

RoboPilot, New Scientist, 9 Jan 2019

Unlike a traditional autopilot, the ROBOpilot Unmanned Aircraft Conversion System literally takes the controls, pressing on foot pedals and handling the yoke using robotic arms. It reads the dials and meters with a computer vision system.

Most of we human pilots who have been around for a while are prone to rejoicing the fact the long awaited pilot shortage is here. Not me. As I near the age where most of my flying will be in back with two youngsters up front, I fear the day it will be one youngster up front and I am certain I will be around for that to happen. What really scares me, however, is the day it becomes no youngsters up front.

I read a study a while back that asked members of the flying public if they would give up the second pilot on an airline flight they are aboard if it meant the would save five dollars on the ticket. The results were predictable: an overwhelming majority said no. But buried in the study was this: a majority of the millennials asked said yes.

So that leads me to the 100 year prediction: Beam me up, Scotty.

— James Albright

References

(Source material)

Barraclough, Martin, The Race for the Cape: A History of the Record-Breaking Flights Between London and Cape Town, 1920 - 2010, Words by Design, U.K., 2016

Hambling, David, New Scientist, 9 September 2019,