When I was an Air Staff Officer at the Pentagon, we would say you could always spot the expert in the room, since he or she would be the one with the stack of slides. But I learned even before then the "expert" was the person with the title.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-11-01

You probably know the problem with that intuitively. In the words of Master Yoda, "a title does not an expert make." But knowing that does not prevent you from falling into their traps. Allow me two examples to illustrate how to detect and how to defeat the false expert. The first was from four decades ago. The second was from this week.

1 — An old example: the P&D valve

1

An old example: the P&D valve

My first operational assignment in the Air Force was to fly the KC-135A, which was a Boeing 717 in the days before Boeing reused that number for another aircraft. The KC-135A had straight turbojet engines, Pratt and Whitney J57-P-43Ws with water injection.

The KC-135A engines had something called a "Pressurizing and Dump Valve" (see the bottom left corner of the image) that had to be purged prior to shutdown to avoid a nasty fuel spill on the pavement. You did this by running the engine up for 30 seconds and then going straight to cutoff.

My next assignment was to fly the EC-135J, which was a Boeing 707. It was heavier and had larger turbo fan engines, Pratt and Whitney TF33-P-9s. These engines also had a P&D valve, but they did not need the 30 second run up to avoid fuel dumping onto the ground.

When I first showed up to that squadron, all of the pilots did the 30 second run up except when we were doing a VIP arrival. In those cases, we just shut the engines down. I noticed the engines didn't dump the fuel the way they did in the KC-135A.

I was a copilot at the time so I asked all the "aircraft commanders" who told me it was still needed, pointing to the fuel system diagram that also had a P&D valve. When I pointed out the fuel wasn't dumping, I was referred to others with more important titles, such as "instructor pilot" or "flight examiner." They assured me that it was true.

Years later, when I had one of those important titles, I got a chance to talk to someone at what the Air Force calls a "System Program Office." I found someone who had been on the original design team and he was surprised. He said our engine had a canister which prevented fuel dumping after a normal flight and idle time. He told me no other users of that engine were doing the 30 second run up.

Our fleet of "experts" immediately adopted the new procedure, saying they knew it all along but their hands were tied by "the system."

2

A new example: flight control checks

The topic of flight control checks tends to be a sore subject in the Gulfstream world after the crash of Gulfstream IV N121JM. The crew of that airplane forgot to disengage their gust lock and skipped the flight control check that would have caught their error. Everyone on board died as a result. Years later Gulfstream crews were still neglecting to do the flight control check.

Gulfstream now tracks all this using Flight Operations Quality Assurance (FOQA) data and reported earlier in 2021 that the percentage of crews doing the check was abysmal. Their aim was to use FOQA to fix that, which is admirable. But the experts didn't understand the data and were pushing procedures onto us in the field that didn't make sense.

Gulfstream GVII-G500 on approach to Henderson Executive (KHND), 19 October 2019, (Matt Birch, http://visualapproachimages.com)

A "Senior Production Test Pilot" — our expert — put out a video that told us in the GVII-G500 world that in order to do a flight control check, we needed to:

- SPEED BRAKE . . . Extend

- Stick . . . Input full left, pause 2 seconds

- Stick . . . Input full right, pause 2 seconds

- SPEED BRAKE . . . Retract

- Stick . . . Input full left, pause 2 seconds

- Stick . . . Input full right, pause 2 seconds

- Stick . . . Release

- Stick . . . Input full forward, pause 2 seconds

- Stick . . . Input full aft, pause 2 seconds

- Stick . . . Release

- Rudder Pedal . . . Input full left, pause 2 seconds

- Rudder Pedal . . . Input full right, pause 2 seconds

- Rudder . . . Pedal Release

The 2 second pause is not in the manuals and we've never done that. In the year and a half we've operated the aircraft, we've never been flagged for skipping the flight control check. I contacted the "expert" who did the video and who checked our FOQA data and congratulated us for doing proper flight control checks.

Trap One: Group think

In cases like this, the crowd tends to immediately surrender as if to say, "if the experts say it is so, it must be so." I heard others say that we must have been doing the two-second pause since we were not being flagged. I challenged the "expert," saying we don't do the pause and insisting that we pilots do the pause will only encourage pilots to skip the check altogether. Why do I say that? The "expert" loses credibility when operators discover the two second rule is a lie. If the expert is wrong about the two seconds, perhaps the "expert" is wrong about the need to do the flight control check in the first place.

Trap Two: Invent metrics

The expert referred me to his video which spoke of the "Flight Control Incomplete Metric." He showed a chart that shows the metric started at over 14% and is now down to below 5% so it has been very successful. You don't want to argue with success, do you?

The expert told us that FOQA looks for full control deflection in each axis sometime between engine start and before takeoff rotation. We were never flagged, therefore we must have been doing the two second pause.

Trap Three: Produce a table or chart about "something"

The video presentation includes a table of "FCC Sampling Rates" for various aircraft. The Flight Control Computer sampling rate for the G500 was listed as 2 seconds. This might be true, I don't know. But the table includes at least four aircraft that don't have FCCs: the GIV, GV, G450, and G550. Where is FOQA getting the data for these aircraft? Could it be that the FOQA data doesn't come from the FCC at all and that the FCC sampling rate doesn't matter?

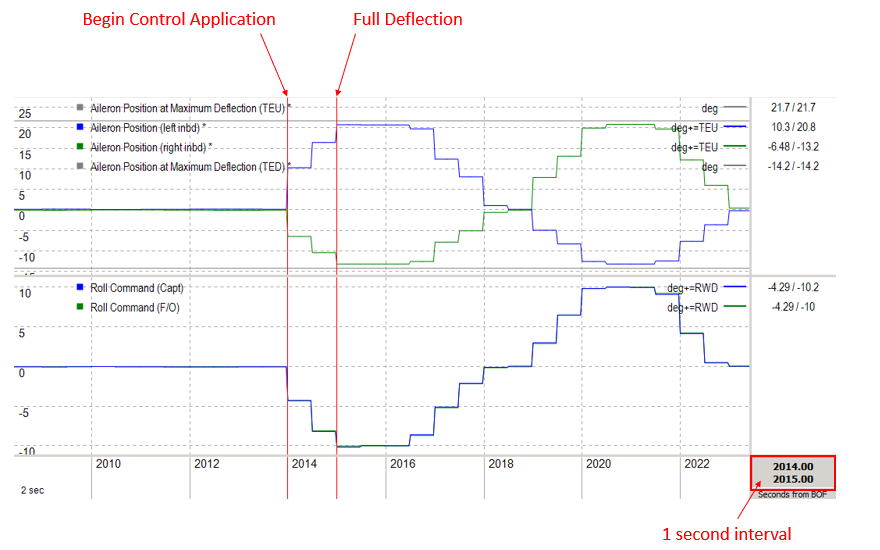

I asked the "expert" directly about this and was told the sampling rate was reduced and he provided me with the chart shown. But he didn't tell me what the rate was reduced to. The chart, I think, was designed to convince me I was fighting science.

Trap Four: Throw in some jargon

When I pressed the "expert" for how long we need to be holding each axis, he said, "Engineering has developed a solution to increase the sampling rate from 1 Hz (2 seconds) to 4 Hz (0.5 seconds) and will be cut-in the production line for G500 and G600 but it is currently not available to the fleet." Further, he said our aircraft "has software requiring a 2 second (1 Hz) dwell time to register a complete flight control check in all axis."

When I pointed out that the definition of Hz (hertz) was cycles per second and 1 Hz is actually 1 cycle per second (not 2) AND 4 Hz is 4 cycles per second not 0.5), he agreed. He said, "Sorry for the confusion converting Hz to seconds on the email below." I guess I was confused.

Trap Five: Misdirection

The "expert" still insisted we must have been holding each axis for the full two seconds because otherwise FOQA would have flagged us. I sent him this video: Flight Control Check. There is a time code on the video that reads hours:minutes:seconds:frames and the video is shot at 24 frames/second. The aileron check takes longer than the others since we have to wait for the spoilers to react. But you can see the pilot takes less than 2 seconds at each aileron full deflection and less than 1 second for the elevator and rudder.

The "expert" was undaunted, saying "For the G500 fleet, we have less than a 0.5 per 100 sorties event rate for incomplete flight control checks. Still not 0 but we will keep targeting the 0 metric for this event." Which of course doesn't address the question at all.

After it was all said and done, the "expert" said our aircraft "is running the AHTMS 3.6 software which has aileron, elevator, and rudder sampling at the 2 Hz rate which equates to the AHTMU recording flight control position twice per second." It appears to me he produced the original video thinking 2 Hz means once every two seconds, nobody questioned that until we came along, and he insisted his original statement in the video was correct until he just couldn't fight the evidence any more.

3

Dealing with experts

So I've provided two examples where the "experts" didn't know what they were talking about but tried to convince me otherwise. It is more than an academic question, because they are using their claimed expertise to impact how I will fly my airplane. What is to be done about this?

- Start with an open mind

- Apply common sense

- Beware of the "everyone says" answer

- Don't accept their assumptions or definitions

- Make sure their answer addresses your question

- Keep records

Many "experts" earn the title through hard work and genuine expertise. You shouldn't discount an unknown expert because that expert may be giving you just the solution you need.

There are things in aviation that don't make common sense because aviation itself doesn't make common sense. We are, after all, in the business of defying gravity. But for the most part, if an answer appears silly on the face, it probably is.

Conventional wisdom has a finite shelf life and needs to be re-examined now and then. The "everyone" includes written source material from highly trusted sources. For just one example, think of all the trusted sources that encouraged you to dive and drive on a non-precision approach.

We don't have to assume a flight must be made or that a successful outcome depends on a feather-soft touchdown on any runway. We need to decide for ourselves what the question is so that we can evaluate the answer.

When faced with the realization their expertise is false, many "experts" will resort to the art of Sophistry. You need to keep focus on what your problem is if you hope to find a solution.

We can't know everything and that means we are often at the mercy of others who wear the title "expert." You probably have a subconscious list of "experts" who have let you down and those that have proven invaluable. Make it a conscious list by keeping records.

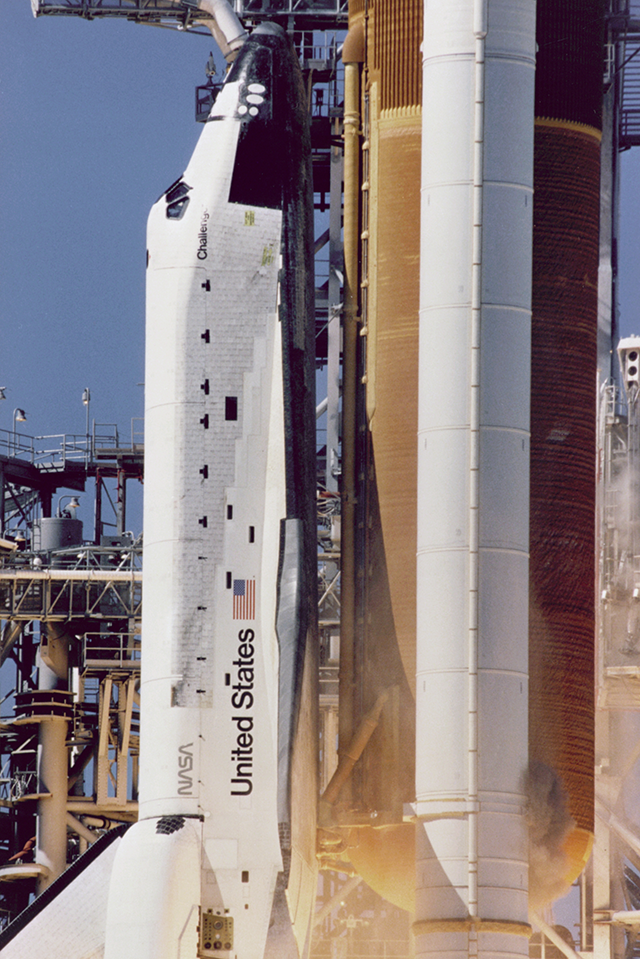

A good case study for how listening to experts can cloud your decision making is the flawed Space Shuttle Challenger launch decision in 1986. There were a lot of top notch experts who were blind to what in hindsight was obvious. These experts at NASA were victims to the normalization of deviance. It is a battle for us in the lower atmosphere as well. What we do for a living is so complicated that we must deal with experts. We need to make sure we can tell the real experts from those who are experts in name only.

a-1_p_1-9.jpg)