Just over forty years ago, August of 1984, I was an Air Force captain flying EC-135Js (Boeing 707s) between California and Hawaii, over and over again, usually a 5.5 hour sortie to California and a 6.5 hour return trip. That was also the month I got called into wing headquarters and was volunteered to take over the base’s flight safety office. The news of the month was that a young pilot had ditched somewhere between California and Hawaii. The bigger news was that she was flying a Cessna 182. Since it was a civilian aircraft and didn’t involve our airport, it wasn’t my concern. My first reaction: how long a flight is that? Answer: 17 to 18 hours. My second reaction: flying a Cessna 182 over that 2,500 mile stretch of ocean is nuts. Since then, I’ve learned it is a highly specialized skill for specialized pilots with a specialized tolerance for nuts.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-01-13

Last month I got an email out of the blue, which read in part:

Hello James,

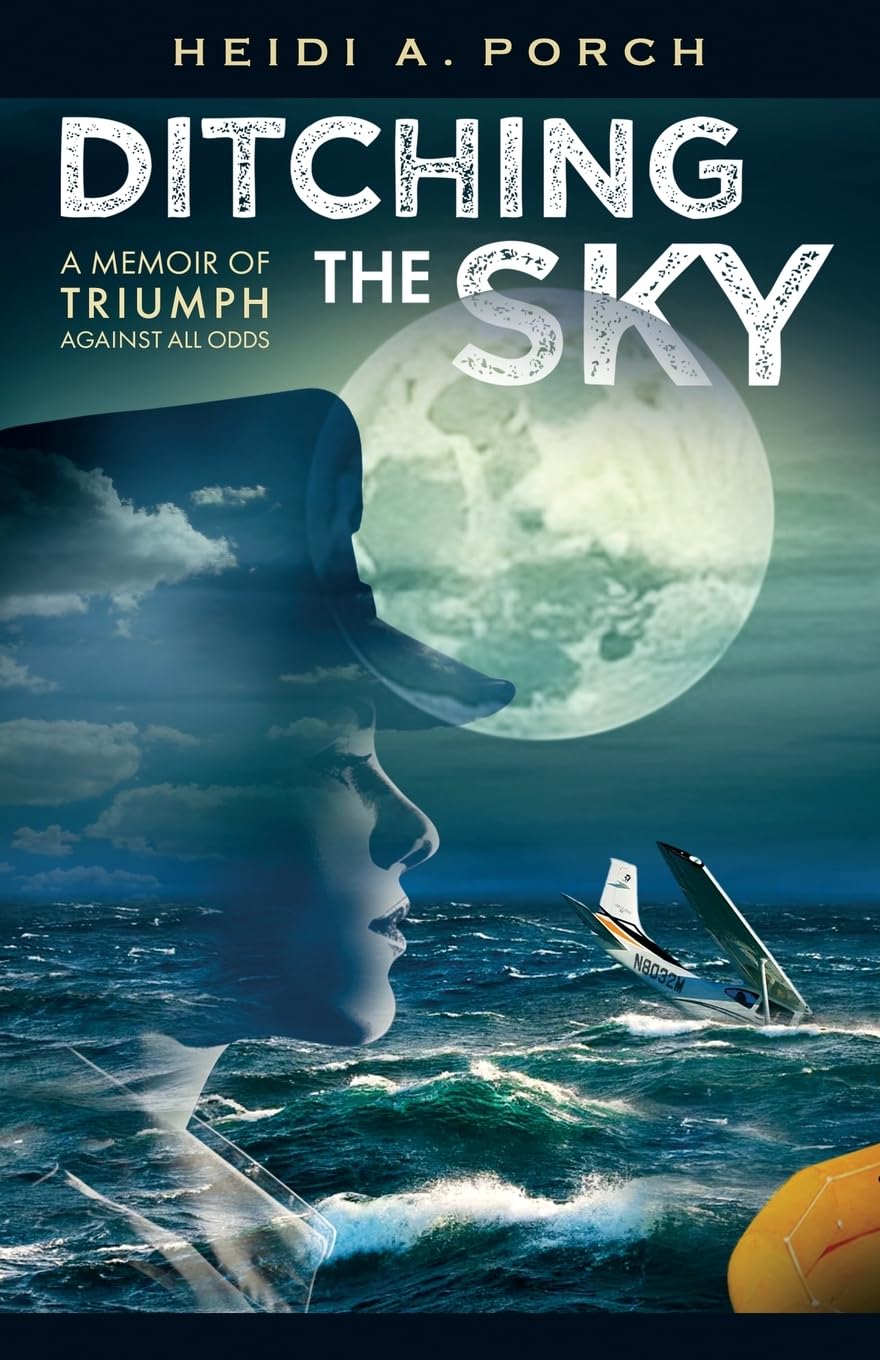

I am retired from flying now, which allowed me the time I needed to finally write a memoir about my experiences ferrying single-engine Cessnas from the United States throughout the Pacific Ocean, to destinations of Australia and New Zealand. On one of these flights, I was delivering a Cessna 182, fixed-gear, from California to New Zealand. On the first leg to Honolulu, the engine was starved of oil, and eventually failed. I was over 500 miles off the coast of Hawaii. I ditched successfully, spent over nine hours in a life raft, and was eventually rescued by a Soviet refrigeration vessel. This all happened during the Cold War; 1984.

Would you be interested, or willing, to read my book, Ditching the Sky? I would be happy to send you a copy if you could provide me with your mailing address. I hope you have a wonderful holiday season, and I look forward to hearing from you.

Heidi Porch

Captain - retired, Delta Air Lines

I get these kinds of requests all the time and usually say thanks, but I just don’t have the time. I’ve found that most pilot-written autobiographies suffer from several problems, top of which is they are usually quite dull. We pilots tend to think we have exciting lives. We defy gravity for a living! But how exciting can flying an airliner from Point A to Point B really be, when thousands of other pilots are doing the same thing routinely? Captain Porch’s story, however, is something completely alien to most of us professional pilots. I quickly agreed.

The first chapter starts with, “Okay Heidi. Master Switch off. Good luck.” It ends with one word: “Impact.” The second chapter begins, “I was five years old.” Oh no, I thought. We are doing a life story here. And it started so well. But as I continued, I realized her approach to this story was as it has to be. Time for a “but, I digress” interlude.

There have been a few times over the years flying across vast expanses of ocean where I answered the call of a light aircraft looking for a navigation fix in the days before GPS, and lately to simply relay a position report. I imagine that flying a single-engine prop with an extended-range fuel tank belted to the right pilot’s seat takes some nerve. In 1984, you might have a LORAN signal for part of the way, but most of your navigation would be by dead reckoning. What kind of pilot is willing to do that?

“Ditching the Sky” introduces you to that five-year-old girl and answers the “what kind of pilot” question. You get to know the single-minded focus that drove Heidi to find a way to an airline cockpit, even if that meant becoming a ferry pilot initially. And her name bears mentioning here. I try to treat people with earned respect and that includes earned titles. As a retired airline captain, she is Captain Porch. But you can’t last more than the first two chapters of this book without thinking of her as Heidi. You feel a friendship growing.

Along the way you learn a thing or two about the art of dead reckoning over thousands of miles and the value of solid planning and preparation. If you’ve logged enough hours as a pilot that you think of yourself as an aviator, you’ll appreciate that Heidi survived the ditching not only because of the hours of planning and preparation, but because of a pragmatic mindset captured in Tom Wolf’s “The Right Stuff.” “I’ve tried A, I’ve tried B, now what do I do?”

I once led a squadron into combat and was astounded how some pilots rose to the challenge while others withered. How will you react when the missiles fly or when the engine, your only engine, quits? Heidi takes you into her head as she faces the moment that she had trained for, but hoped would never happen. If you fly for a living, you need to “chair fly” the ditching with her. The exercise will make you a better pilot.

It should be obvious that I very much liked this book and highly recommend it. Get it at Amazon.

Even if you don’t fly light aircraft thousands of miles from land for a living, there is risk in all parts of aviation. The book will help you to inventory what you need to do to prepare your loved ones if something tragic happens. And if you survive, how will you calm your family that feared the worst? Here’s how Heidi did it.

“Hi Mom. A funny thing happened on the way to Hawaii.”

Heidi in the raft next to her Cessna 182, taken by her wingman.