I used to give four or five speeches a year but stopped doing that a few years ago when I retired from actively flying and writing for various magazines. Last month I made an exception for a friend and thought maybe it might be of interest.

— James Albright

I'm often asked to provide a bio for the purposes of writing an introduction. So, in today’s age of Artificial Intelligence, I gave ChatGPT my bio but didn't like the result. So I just asked it to draw a photo of an old pilot next to an airplane. See the problem with the photo? If you are worried about AI taking over the world soon, don't be.

My objective today is to pass along five lessons I’ve learned that you may not have heard expressed in the same way: Don’t be an ape. Don’t get smart. Don’t get busy. Don’t panic. Do things for a reason. I remember them this way to keep them fresh in my mind. I hope they do the same for you.

Don't be an ape

I’ve been guilty of flying like an ape. I’ve known pilots who are apes. In fact, I’ve known mechanics and flight attendants who behave like apes. But the liability for those who are apes is greatest for us pilots. Thankfully, we can rely on mechanics and flight attendants to bring this to our attention. For me, the realization came early.

This is the mighty Northrop T-38, what the Air Force calls the Talon, but we called it the White Rocket. This was back in 1979, the same year it was flown by the Air Force Thunderbirds. That’s me in the front seat of lead. Number four moved out of position to take this photo.

The T-38, back then, could pull 7.33 Gs. I have a low tolerance for Gs. The problem is that when you pull Gs, the blood leaves your brain and rushes to your torso and legs. But we wore G-suits which clamped down on our legs and torso, forcing the blood back. This wasn’t enough for me, so I learned early a breathing exercise to help, and from that point I had no problems.

And that, in itself was a problem. If the maneuver called for 5-1/2 Gs, as a loop did, I would just pile on the Gs. One second we were doing 1 G – straight and level – the next I was doing 5-1/2. As a student, we started doing loops at full military power, which means all the power we have except the afterburners. So I would pile on the Gs, fly the loop, and press on. I was always graded satisfactory. After we got good at this and passed our first checkride, we were required to do our loops using less thrust. I think it was 95%. I would go into the maneuver, as always, pile on the Gs, but then I would run out of airspeed before I got to the top of the loop, inverted, and would have to abort. I became very frustrated. My instructor became very frustrated too and scheduled me to fly with another IP to see if they could fix what was broken.

The second IP identified the problem immediately: “You fly like an ape.” I learned that when you go from 1 to 5-1/2 Gs immediately, you burn off more energy than if you bring on the Gs more gradually, say in two or three seconds. That was the day I learned what finesse means, and stopped flying like an ape.

Saying you have no finesse, or you fly like an ape, is a huge insult in the pilot world. It rarely gets the message across. Sometimes the message is best delivered by someone who is highly respected, and not a pilot.

And that leads me to my first job as a civilian pilot, flying these Challengers for Compaq Computer, right here in Houston. We were parked overnight at Hanscom Field, with our tail hanging over the grass near Taxiway Sierra. We came to our aircraft that morning and found a long gash along the horizontal stabilizer, parallel to the taxiway. That morning, a brand-new Netjets BBJ taxied by and its winglet sliced our stab. The BBJ took off, landed in Hawaii with much of its right winglet missing. They’ve since moved that ramp further away from Taxiway Sierra.

The good folks at Bombardier replaced our horizontal stabilizer and provided a test pilot to do the test flight, but required we provide the other pilot. I got the call. So there we were, the Bombardier pilot in the left seat, me in the right, and our Director of Maintenance on the jumpseat. Everything started to go wrong during the takeoff rotation. The test pilot pulled back too hard on the yoke, I thought we might have a tail strike. I pushed forward on the yoke and said, “don’t be an ape.”

Our mechanic was furious. He told the test pilot, rightly, that the manual says rotation had to be done 3 degrees per second. He said test pilots were allowed to be quicker.

He was one the roughest pilots I’ve ever flown with. Maneuver after maneuver. But we got the test card completed until the last item: a sustained 2 G pull. The Bombardier test pilot said they always skipped this maneuver because the airplane didn’t have a G-meter and there was no way to ensure we only had 2 Gs on the airplane.

Any private pilots in the audience? How do you know you have 2 Gs on the airplane in level flight? That’s right, a 60° bank turn in level flight. Our test pilot said, “I guess that will work.” He rolled the airplane so quickly the wings shuddered. I took the airplane again.

Our Director of Maintenance said to the test pilot while pointing to me, “he’s flying the airplane home. If you touch the controls again, the next thing you are going to feel is a crash axe in the back of your skull.” Our mechanic understood the difference between dynamic/impact and static loads. Structures can take a higher load without deforming, or breaking, if the force is applied gradually. He knew that you shouldn’t fly airplanes like an ape.

We bought this aircraft, a GVII-G500, before the type was certified. This was its first flight after getting its paint job, but before it got our tail number. An interesting thing about flying an airplane that has just been certified, is that you the crew are learning it even as the manufacturer is. I was in class number nine, and my sim partner was a Gulfstream test pilot, learning to fly it just as I was.

We pilots tend to think we’re something special, we all know that. But when the airplane is brand-new, our egos get the better of us. Our instructors had shirts that said, “G500 Initial Cadre.” Because they were special. They told us we were only the ninth class. Because we were special.

And there is something to it. Not every pilot has the chops to fly a Gulfstream. But something to keep in mind is that sometimes, you might just be there because you had a pulse and it was cheaper to send you than hire someone new.

What I’m saying here is that don’t be surprised to find out there are apes flying the same aircraft as you.

We found that out in the first year of operations, a G500 had a very hard landing that was hard enough to bottom out the struts and damage the gear doors. And it happened twice. I had written about the fly-by-wire system for Aviation Week and a friend of one of the hard landing pilots wanted me to write that it was the fault of the fly-by-wire system. His friend, he said, was an excellent pilot.

I waited for the preliminaries and am glad I did. In both cases, the pilots did not apply any wind gust additive. In both cases, the pilots had gone from stick full forward to full aft repeatedly in a matter of seconds just prior to the flare. Because of the rapid fore and aft stick, the fly-by-wire system limited the amount of alpha available. When the pilots asked for full aft stick in the flare, they didn’t get it because of alpha limiting.

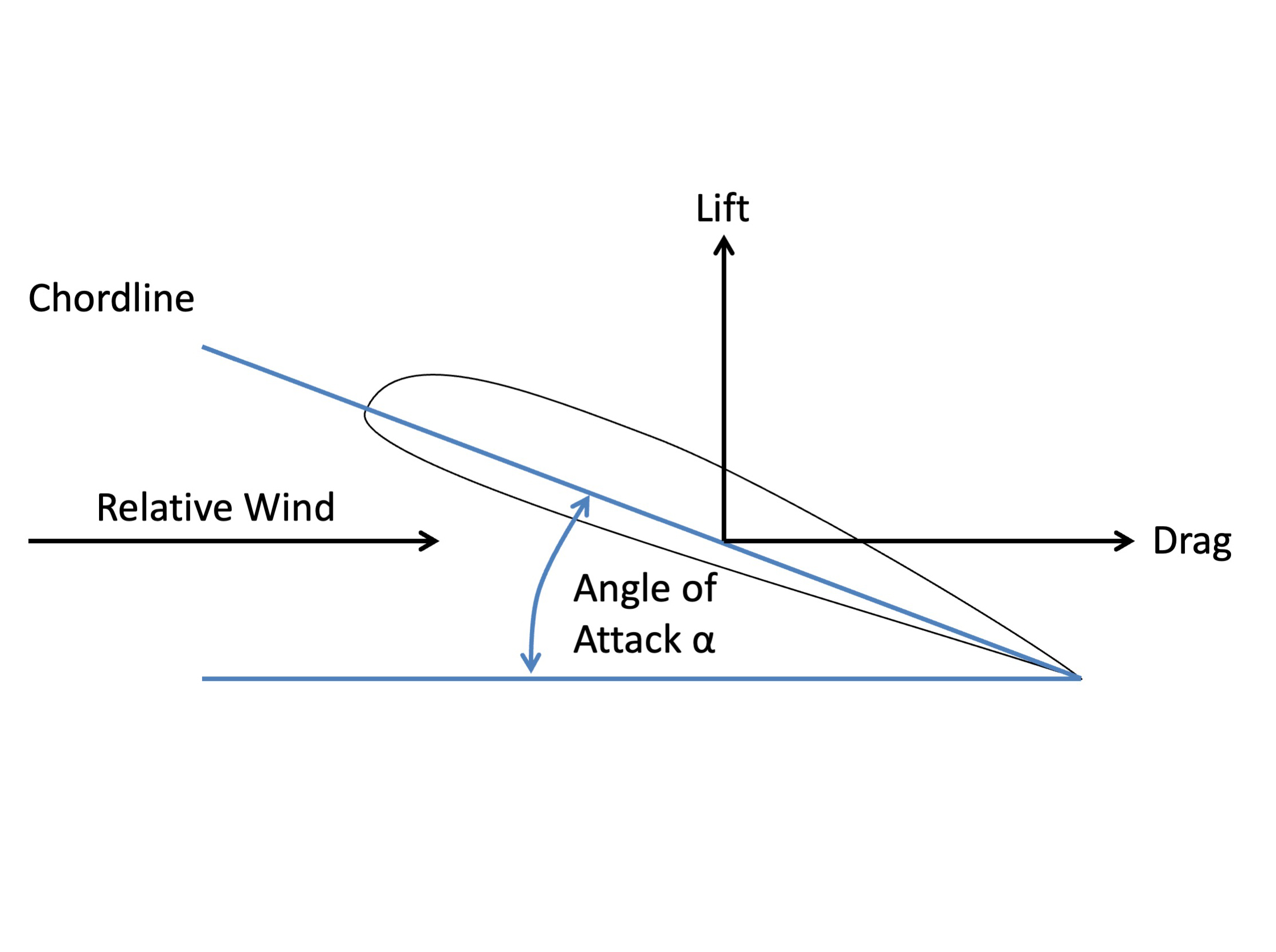

Question: in your GVII’s fly-by-wire system, what is it that “Alpha Limiting” limits?

Yes, AOA, spelled out Angle of Attack.

If Alpha means AOA to an engineer, what would the next letter in the alphabet be called? It isn’t Bravo. Alpha, Bravo, Charlie is what some called the ICAO alphabet, but it is actually from NATO. Engineers, for some reason, speak Latin and the next letter is Beta.

So here is question two. So if Alpha Protection guards AOA, what does Beta mean and what does Beta Protection protect us from?

Beta means sideslip, and we also have Beta protection.

Alpha protection and beta protection. What are they protecting us from?

I know this is a gross simplification, but you can think of alpha protection as protecting the airplane from a stall and beta protection as protecting us from losing control of the aircraft. You may have known that. But did you know that beta affects alpha? The more beta (sideslip) you have, the less alpha (AOA) you have available.

Most of us know you shouldn’t do rapid rudder reversals, as the pilots of the American Airlines Airbus found out back in 2001 out of JFK, they twisted the tail right off the airplane. But the same warning applies to each axis: no rapid control reversals in ailerons or elevator. It says so right in your manual.

You might argue that landing at Teterboro on a gusty day sometimes requires extraordinary control inputs. I think you should restrain yourself from doing that. If you find yourself going to the stops forward or aft, or if you just find yourself pumping the stick, try this. Just freeze the stick, slightly aft, for two seconds. You might be surprised to see how everything settles down. If you are too low to the ground to do this, go around.

And as far as pumping the stick, don’t be an ape.

Don't get smart

So that was rule one: don’t be an ape.

Now for rule two: don’t get smart.

Let’s face it, if you are operating or maintaining an airplane of the caliber of a Gulfstream or a Praetor, you must be pretty smart. And you make this journey to becoming smart with each new airplane. On day one at initial, you were a dummy. And before you know it, you’re an expert. And the longer you’ve been in aviation, the faster you make the jump from dummy to expert.

So, you must be smart. The problem with your expertise, however, is you may become tempted to think you are smarter than the airplane and those who designed it.

They say you know you are an old aviator when aircraft you’ve flown show up in museums. I flew this airplane for the 89th Airlift Wing at Andrews, now it is at the National Museum of the Air Force.

I was flying this airplane into Madrid after the flaps had failed in the up position. We didn’t know they had failed until about five minutes before landing. We completed the checklists and landed. The flight attendant said she noticed things were whizzing by quickly on short final, but had no comments later.

Years later, I was in the same situation going into Washington National, flying a Challenger 604. I reacted the same as I had done in the Air Force, ten years earlier. After the passengers were on their way, the flight attendant asked why we were so fast on final, so I told her. She was furious. “It’s an emergency procedure and you didn’t tell me? What if we had to do a ground egress? What if the brakes caught fire? What if, what if, what if?”

Of course she was right. Thanks to her, I now include the flight attendant in all these decisions. I thought I was so smart, I could consider everything. I hadn’t considered the ground evacuation complication. I have to remind myself all the time: don’t get smart.

My first Gulfstreams were three different models of Air Force GIIIs, then the GV, then the GIV. I was hired to be the third line pilot in a flight department of three pilots. In other words, I was the low man on the totem pole. As part of my indoc, I was required to fly three takeoffs and landings at our home airport. The aircraft was light and my first landing was in the touchdown zone, I used full reverse, and I never touched the brakes until 70 knots. The brake temps were over 200 degrees. The boss said that was normal for a GIV. I left the gear down for the next two patterns and the results were the same. I asked the mechanic who told me that’s the way GIVs are.

Our first trip away from home was a weeklong affair and I noticed the brakes didn’t get as hot, but were still hotter than they should have been. With each passing day, they got better. After we came home, I told the mechanic the brakes were fine. The next trip, the brakes reached 200 degrees again. Once again, the mechanic said that was normal.

After that flight, I noticed the mechanic spraying MEK, Methyl Ethyl Ketone, on each brake puck. I asked him why he did that, he told me he was using MEK on brakes since his first job as an A&P. I told him that I was told the only thing you clean brakes with is compressed air or water. And if you use water, you have to give them time to dry. He told me to mind my own business.

An hour later I saw him hosing down the brakes with water. He told me that he finally asked Gulfstream and they told him the same thing I did. Then he read the label on the bottle of MEK. As you mechanics know, MEK is highly flammable.

The lesson is obvious: don’t think you have a better way than all who came before you without evidence. Don’t get smart.

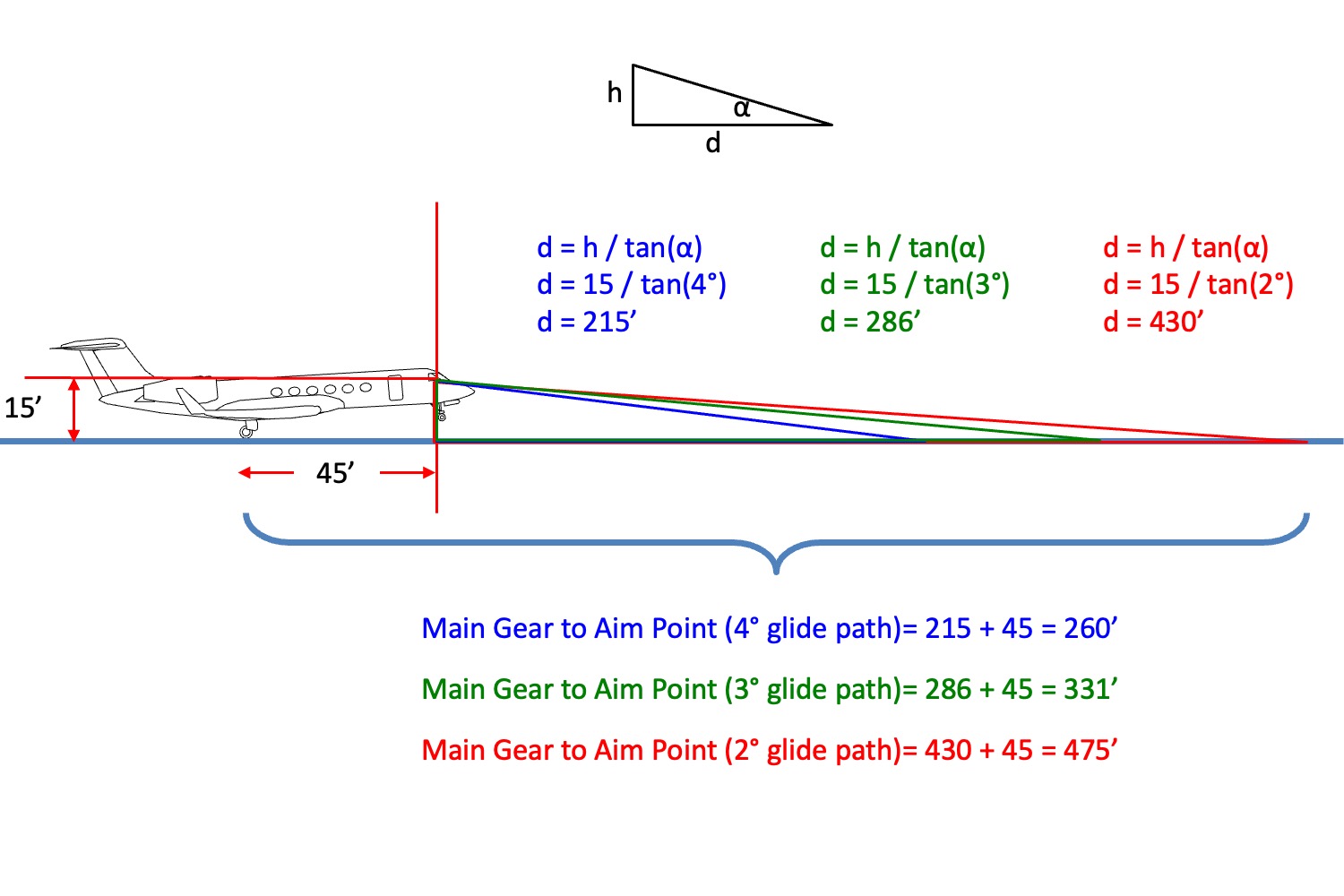

Like our mechanic moving from a GIV to a G450, we pilots are often guilty of assuming that a new aircraft to us flies just like the aircraft we’ve flown before. So here’s a question for you in the G600. Let’s say your technique for landing on a short runway is to aim for the first touchdown zone marking, 500 feet down the runway. Your plan is to flare, after all, and that should take the wheels to the touchdown zone, 1,000 feet down the runway. I was actually taught this technique in the Air Force. During my time in the Boeing 747, there were 18 wheel prints in the overrun at Andrews that could have only been made by one kind of airplane.

Now let’s say that for some reason you get distracted and don’t flare? Your eyes are aiming for 500 feet. Where will your wheels touch?

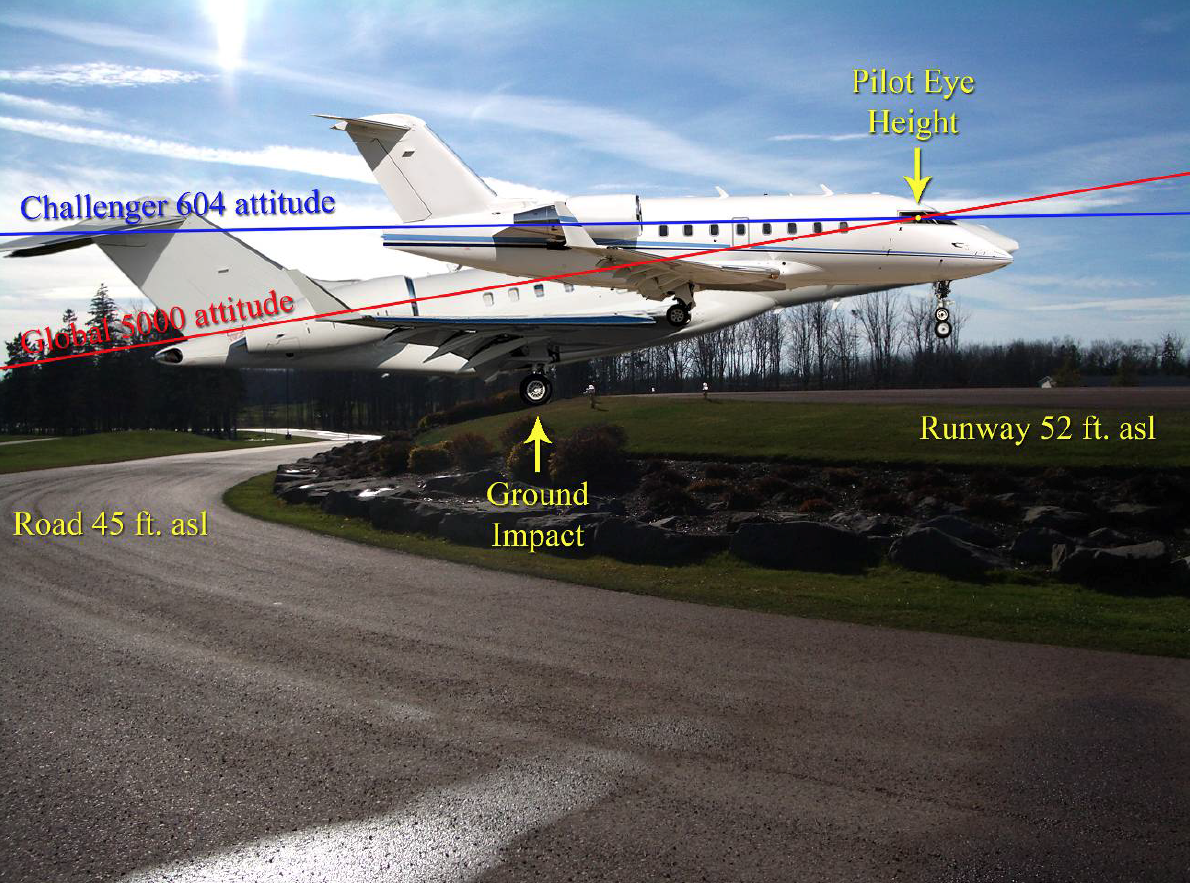

This photo is the aftermath of two highly qualified Challenger pilots landing on a 4,885 foot runway in a brand new Global 5000. The pilot said he was planning to touchdown in the first 500 feet of runway. His main gear contacted a lip 8 feet short of the runway and the aircraft was totaled.

So let’s ask that question in terms of the G600. If you are aiming for 500 feet, don’t flare, where will your wheels touch?

Hint: the distance between where you are sitting in the cockpit and your main landing gear is about 45 feet.

If you said 45 feet, your answer is low, way low. Here’s another hint, the distance has a lot to do with trigonometry and is made even more complicated by the positive deck angle prior to the flare, as well as the height difference of your eyes over the wheels.

I’ve done the math for the G600:

If for some reason you don’t flare, on a 3° glidepath, your main wheels will touchdown 331’ short of your aimpoint. In this case, 169’ down the runway.

Now let’s say your short field landing technique includes a shallow approach angle, let’s say 2° -- I’ve known lots of pilots who do this too. As you can see, it makes things worse.

If you say 169’ down the runway is good enough, let’s throw in some wind gusts.

Now you may say that you won’t forget to flare. Okay, that’s your decision if you think you are smarter than the guys who wrote the certification regulations and the guys who designed the aircraft.

Here, by the way, is a look at what these pilots would see the identical point over that runway. In this photo, their eyes are in the same position. Notice the Challenger has a flatter approach angle and is much shorter. The pilots probably knew this, but they didn’t know it well enough.

My advice to you: don’t get smart.

Don't get busy

So that was “Don’t get smart” – meaning don’t think you know it all based on past experiences or can come up with a new and improved way to do things that nobody has thought of before.

Dovetailing that idea is “don’t get busy”

“Don’t get busy” deals with two problems

First, we can fail to prioritize what is really important because it is easier to be comfortable with what you know. That is why so many accidents happen when the captain decides to fly the airplane when the better idea is often to have the first officer do that while tackling the emergency. We know how to fly. Sometimes tackling the unknown can seem daunting.

Second, we often feel we have to do something, anything, when the better plan might be to delay a few seconds, or minutes, and to think.

Either way, the idea is “don’t get busy.

Here’s one for you mechanics. How often do you do a post-flight inspection and come upon a blood stain and other evidence that a bird met its end flying into your aircraft? What do you do? I think the procedure for a bird strike on a radome involves looking for cracks, delamination, or other evidence of damage. I think checking the inside of the radome is optional. Does that sound right?

Sometimes the damage isn’t obvious, and we are all busy, and the temptation is to sign it off as inspected and a-okay.

That’s what happened to an Air France A350 on April 24, 2023, taking off out of Lagos. The radome was inspected, including the inside, and signed off. Would that be worth a formal write up?

Over the next month, three flights were made with radar faults written up. The Air France procedure was to confirm the faults on the ground and only if confirmed, an inspection is carried out. The faults were not confirmed.

On May 27th, after another write up, an inspection of the inner radome was requested but not carried out. The technician inspected only the exterior. Here is what happened the next day:

On the 28th of May, 2023, the airplane took off out of Osaka, Japan and the weather faults returned. The crew elected to turn around and during descent through FL 300, the radome collapsed on itself.

The crew did a good job getting the airplane on the ground, despite unreliable airspeed indications. The weather was good. The outcome could have been different otherwise.

We are often called to go above and beyond what the book tells us when troubleshooting. I once landed in our G450 when I felt the brakes chattering at my feet. Kind of like an older antiskid system. I wrote it up, the mechanic did all the steps in the maintenance manual and told me it checked good. Was I sure about it? I told him I was.

Our mechanic then took the hubs off the wheels to look at the speed sensors. He came to my desk and presented me ten bits of speed sensor when there should have only been one. He wasn’t too busy to fully troubleshoot and investigate.

Let me ask you pilots this: when must you act immediately? No time for checklists, no time for a crew vote, but you have to act immediately, or bad things will happen.

This is, of course, a personal decision. But for me, the list is rather short: an engine failure at V1, a missed approach at minimums, a CFIT warning, and maybe a Rapid-D. That’s it. You could make an argument for a windshear and a TCAS RA, but I would argue you need to take a few seconds to make a decision. A Rapid-D? Get your mask on, then you have a few seconds to think.

For the rest: the decision is instantaneous. An engine failure at V1? Go. A missed approach at minimums? Go around. A CFIT warning? Escape maneuver? We practice these in the sim and your reactions should be automatic.

We practice engine failures at V1, but pilots mess these up all the time. So it will be worthwhile to dive in a little deeper.

Let’s say it’s one of those days where you are using all of the runway and you are the pilot monitoring. When do you call V1? Many pilots will tell you the call is made at V1 because V1 is “Decision Speed” and they will even tell you that FAR 25 gives you 2 seconds at V1. Is that true?

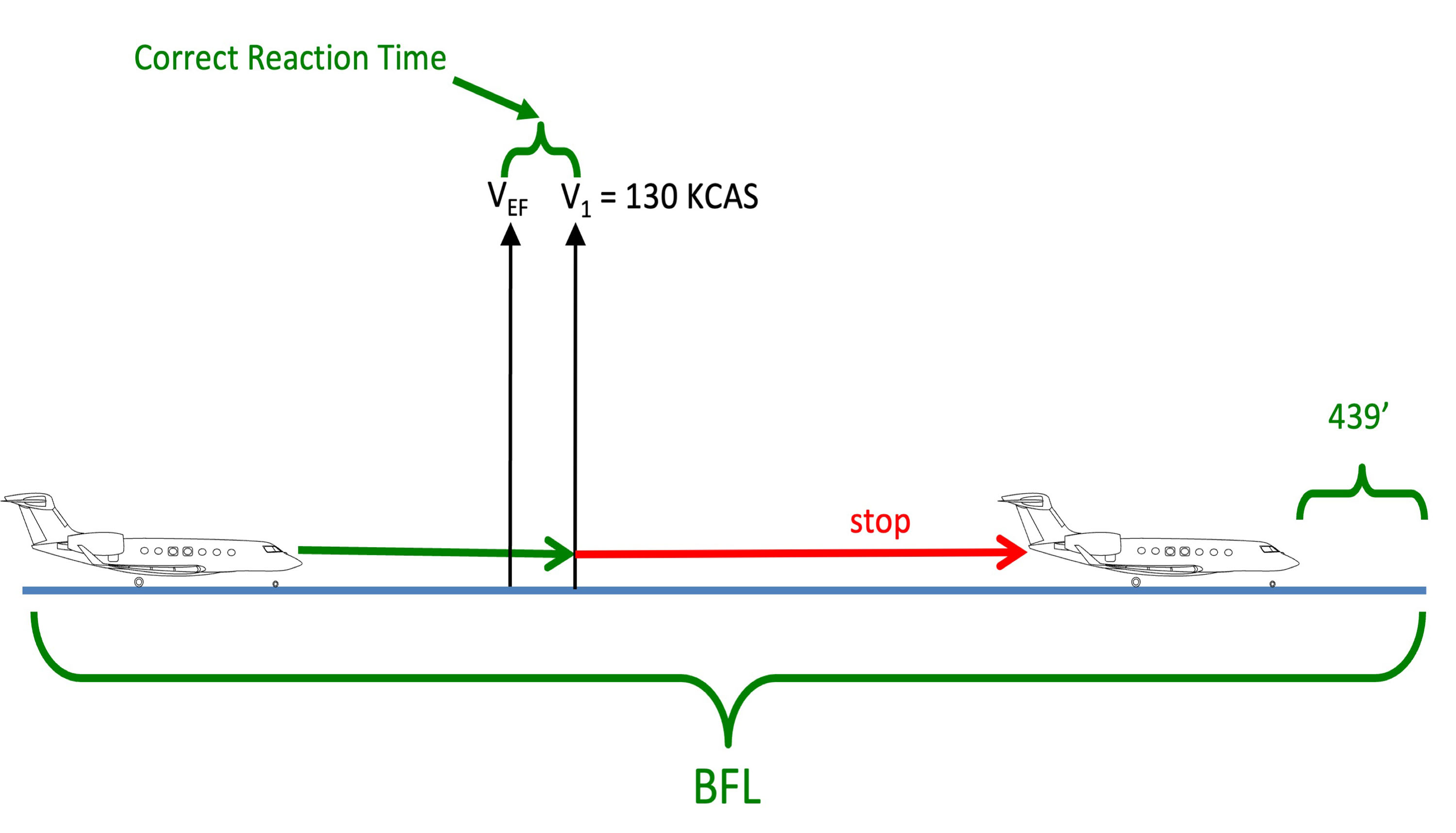

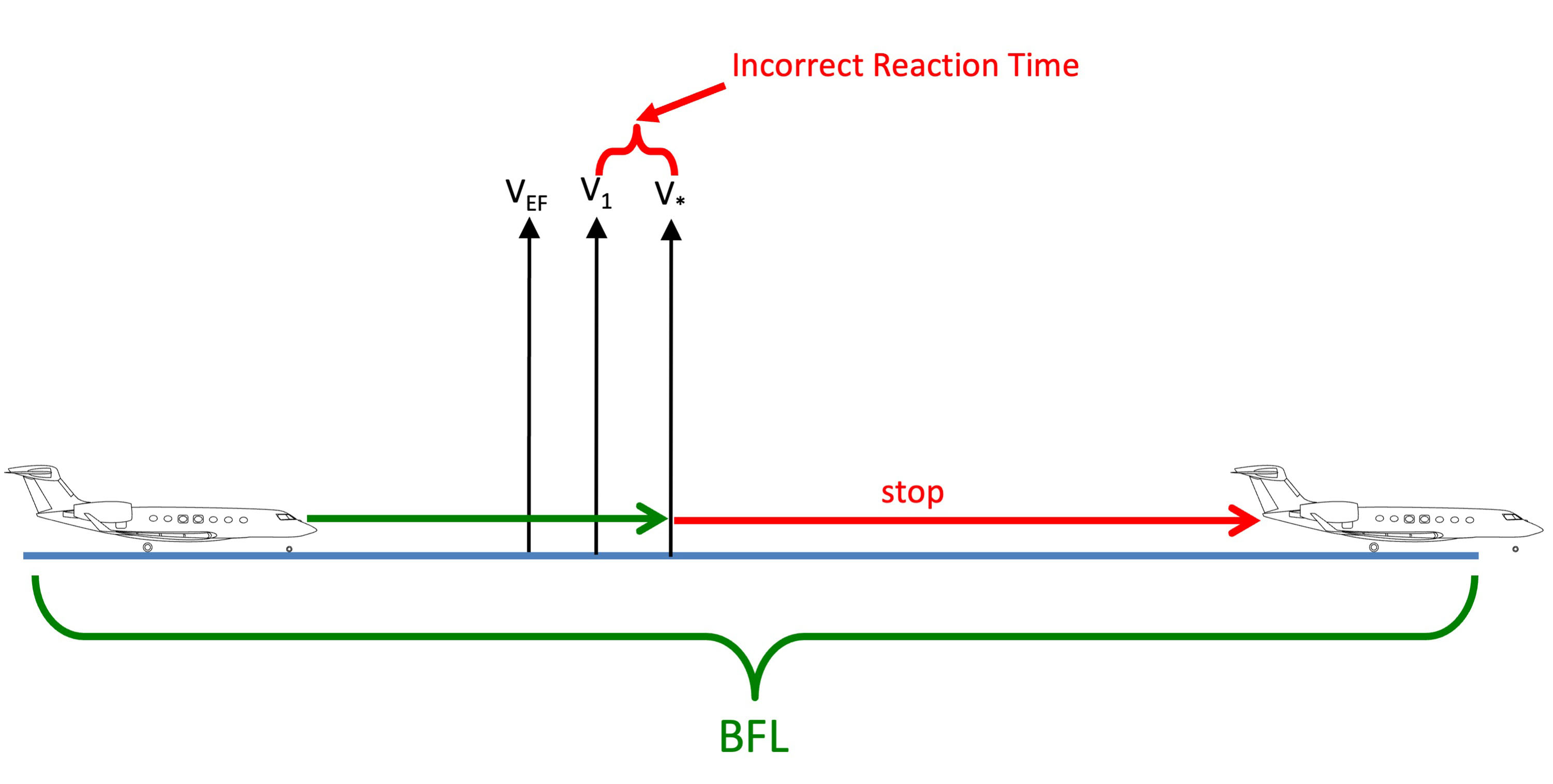

What the regulation actually says is V1 the maximum speed at which the pilot must take the first action to either abort or continue. Action. What about that 2 second reaction time? FAR 25 does mention 2 seconds, but it isn’t a reaction time. It is a safety buffer. You take the speed you are doing at V1, convert that into a distance, and that is how much runway you will have left over as a safety pad. I did the numbers for this example for a V1 of 130 knots, and found you will have 439 feet of runway in front of you when you come to a stop. That’s all.

Here’s what happens if you don’t take that first action until 2 seconds later. You will be amazed at how much faster you are going after 2 seconds with even just one engine pushing. In this case, you will consume an extra 500 feet, meaning you depart the runway’s paved surface.

That’s why this is a situation where you cannot hesitate and the call must be made before V1. How much sooner? They say it takes a typical pilot a second to react, which tells me you must finish saying “V1” about a second before you see V1. In the G600 you have an advantage because you can see V1 in the HUD. Even if the first officer hasn’t said it yet, if you see V1 in the HUD, you are at V1.

So before V1 you’ve rejected the takeoff. After V1 you continue. Now what?

There is an old saying in aviation you may have heard, it starts with two questions. “What is the first thing you need to do when faced with a catastrophic emergency and when should you do that?”

The answer is: “Do nothing, and do that immediately.”

We preach that we’ll do nothing until 400’ or, even better, 1,500’. But why do so many pilots shut down the wrong engine when stressed? I think a main culprit is our inner desire to do something, anything, and to do that right away. This photo, by the way, was taken by a taxi’s dash cam. It was a Transasia ATR 72 in 2015. The right engine flamed out at 1,300 ft . Yes, the right engine. They are rolled to the left because they shut down the left engine and then stalled the airplane.

My technique as the PM is to talk calmly, giving the PF enough data to assure him or her things are not catastrophic and to avoid distracting him or her from flying the aircraft. “Gear is up, climbing nicely. Looks like the left engine has seized.”

My technique as the PF is to fly the airplane and give the PM the information I have to add to his or her situational awareness. “Positive rate, gear up. Wings are level, I have full right rudder and no adverse yaw, continuing the climb on course.”

The pilot flying concentrates on flying, the pilot monitoring does just that. But don’t even think about shutting an engine down until your minimum altitude.

Don't panic

So we don’t fly like apes, we don’t get smart, and we don’t get busy. Related to that last point, it is important that we don’t panic.

I think we pilots as individuals are just as likely to panic as non-pilots, except that we spend so much time being desensitized to it. If you take the simulator seriously, and you should, you get beaten into the idea that when the world falls apart, you need to focus on the task at hand.

My experience in the simulator is that the more time you spend flying at our level of professionalism, the less likely you are to panic.

There is a problem, however, in that we all realize that no matter what happens, we aren’t going to end our simulator session in an ambulance or a body bag.

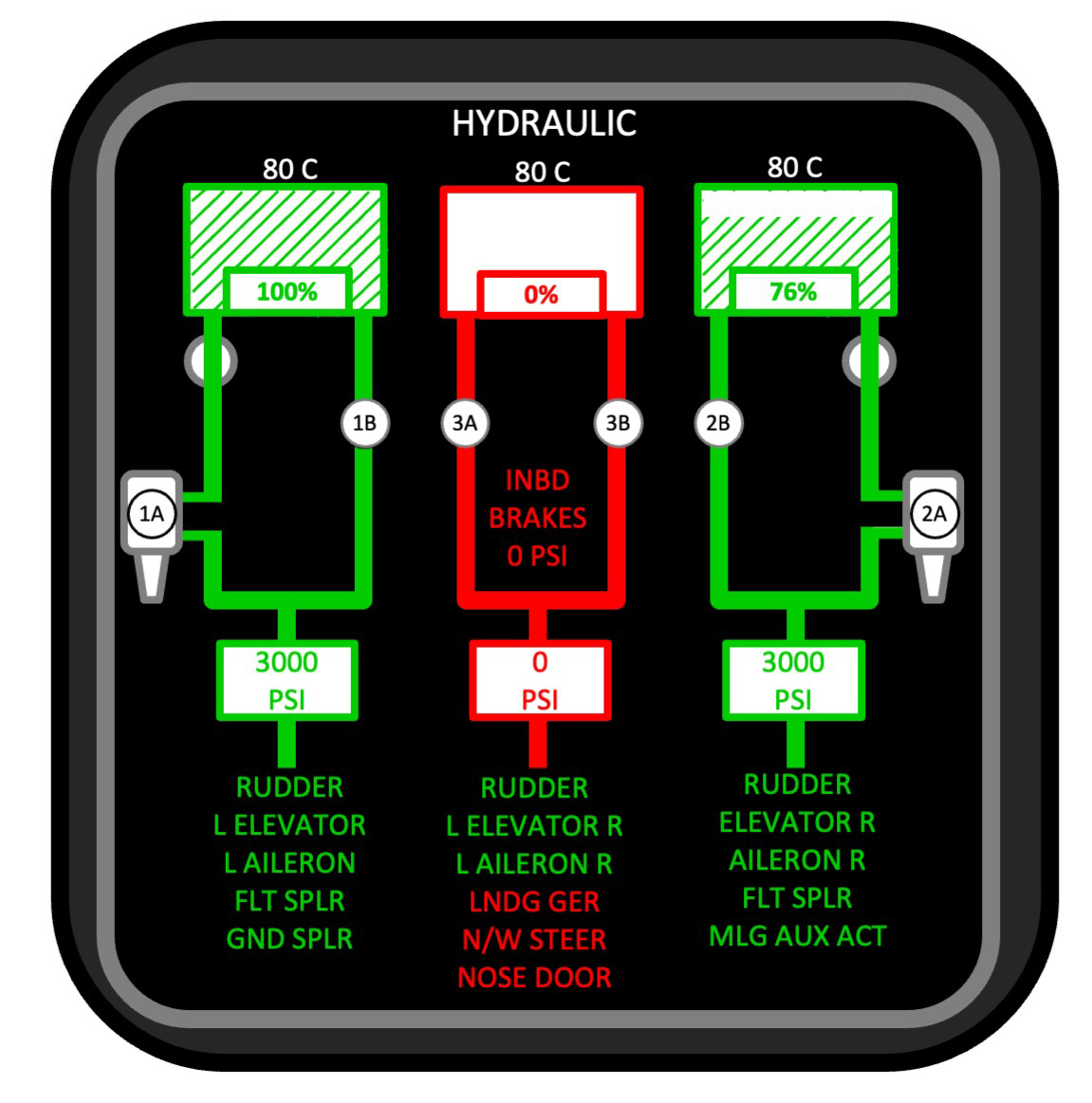

Like with anything else, practice helps. I once lost a hydraulic system after leveling off, en route from Sarasota to Bedford. Not a big deal, this was a Challenger 604 with three hydraulic systems, but we would have to perform an alternate gear extension. I was flying with the flight department’s chief pilot, a man with twice my hours and years flying, but no military pilot experience. I told him to declare an emergency and get clearance to divert into Charleston. To say he panicked would be an understatement. He was hyperventilating, couldn’t run a simple checklist, and the pitch of his voice increased a few octaves. The alternate gear extension handle was between the seats and I had to talk him through the procedure, even though he had practiced it countless times in the simulator.

It wasn’t until we landed that he finally calmed down. That night I asked him why he reacted that way. He said he realized for the first time lives were at stake. He asked me why I didn’t panic. I told him I had lots of practice dealing with these things with lives at stake.

You might be wondering how I got all this practice. I spent many years flying poorly maintained aircraft that tended to fall apart and catch fire, with engines that did the same. Many of you have the same experience, even as civilians.

What if you don’t have that experience? What if your profession doesn’t include simulators or you know deep inside you are walking away from that experience unscathed?

Take for example the flight attendants on Delta Connection Flight 4819 after landing in Toronto last February? There’s little doubt their pilots really screwed up and the airplane ended up inverted on the ground. This photo is of one of the flight attendants standing on the ceiling, calmly guiding the passengers out. If there could be a right stuff award for flight attendants, I think she deserves it.

Some people are just naturally calm under pressure. But what if that doesn’t describe you? I think you can learn the skill. I have two ideas to help you do just that.

I’ve lost engines at V1 three times over the years, all in the Air Force.

The first time was with just a few weeks before graduation from Air Force pilot training, I was taking off from Point Mugu Naval Air Station in the White Rocket, the T-38, when at V1 a bird flew into my left engine and a fire ball spit out the front and back of the engine. I rotated, raised the gear with the windmilling hydraulics, and climbed to pattern altitude. I accomplished checklists, let tower know what I was doing, and came up with an ejection plan away from populated areas if the other engine quit. I landed the airplane and called it a day. The entire flight took six minutes. There was no time to panic, only to follow Standard Operating Procedures. So that is technique one, follow SOPs. It gives your brain something to do, other than panic.

That same year Tom Wolfe’s excellent book, “The Right Stuff” came out and I read it the next year. Something that struck me was a scene in the book where a pilot was wrestling with an airplane to his death saying “I’ve tried A, I’ve tried B, I’ve tried C. What do I do now?” That last bit wasn’t the pilot giving up, it was him coming up with the next plan.

Right after I read the book, I flew to Anderson Air Base in Guam for a month of what was called a “tanker task force.” I took this photo during our first arrival and I got to know the runways well. Where it appears the runway disappears into the Pacific Ocean is a 600 foot cliff. There is a B-52 underwater at the end of that cliff.

I lost my second engine at V1, with most of the runway behind me. V1? No decision to be made, of course I never considered aborting. But with a thousand feet remaining, we were nowhere near rotate speed. I rotated anyway.

So there we were, staggered into the air, all the rudder I had, some aileron, just enough airspeed to stay airborne, but nothing else. “What do I do now?” I traded airspeed for altitude. After we landed the wing commander came to shake the aircraft commander’s hand for saving the airplane. To his credit, he pointed to his second lieutenant copilot and said, “it was him.”

Four years later I lost another engine on another aircraft at Dallas Love Field. Once again, my first thought after I got the airplane climbing was “What do I do now?”

I’ve done this ever since but never really thought about it as a technique until I met Ross Bentley when we shared the stage at an event much like this one.

Ross is a Canadian racecar driver who is now a performance coach.

Ross coaches his racecar drivers to have what he calls a “Pre-Planned Thought,” or PPT. Before coming on a situation that requires concentration and the need to avoid distracting thoughts, he says you should have a short phrase ready to knock yourself into the moment. One that he uses before the starter’s pistol: “Smooth and confident.”

For me, when things go wrong, when I’m done with SOPs, my PPT is “What do I do now?” It gives my mind someplace to go and reminds me that I’ve handled much worse before. That’s my PPT, you should have one that makes sense to you. That’s a good way to avoid panic.

I know I’ve made it sound like we pilots have ice water in our veins and that might be true for some, but the NTSB contains many cases showing pilots who were anything but calm. I’m sure you’ve heard about Air France 447, the Airbus A330 that crashed over the Atlantic. You may have heard the cause was ice crystals in the pitot tubes, or the fact one pilot was pushing the stick down as the other was pulling back, or a number of other explanations. But those aren’t the real cause. The real cause was panic. When the airspeed information went out, the autopilot disengaged and the pilot pulled the stick back to about 16 degrees of pitch. Five minutes later they were dead. Had the pilot simply maintained the pitch he had for a minute, they would have lived.

Let me ask any pilot here. If you are at or near your maximum weight at a normal en route cruise altitude, and you lose all altitude and airspeed information, what’s a good thrust and pitch setting to hold while you troubleshoot?

Knowing the answer can save your aircraft and the lives of everyone on board. It would have saved 228 lives on Air France 447.

Okay, now let’s say you just took off over the ocean at night, with no discernible horizon but you have a good attitude indicator. Now you lose your altitude and airspeed information. What thrust setting and pitch setting? Having that answer would have saved a total of 259 lives in 1996 on two Boeing 757 crashes.

For most of the Gulfstreams that I’ve flown with a FADEC, full thrust and 15 degrees of pitch when low to the ground will keep you climbing. Full thrust and 3 degrees of pitch will keep you from stalling at cruise altitude.

For you pilots, I recommend you repeat the following phrase whenever you have uncertain airspeed and altitude information: “Known thrust and pitch settings.” If it ever happens in the airplane, this PPT can be a game changer.

.jpeg)

Of course, none of this will help if your first inclination in a stressful situation is to erupt in anger, frustration, confusion, or despair. If that describes you, please allow me to offer one final PPT: “A practiced calm serves me well.”

Yes, you can practice being calm.

The next time someone cuts you off in traffic, the next time someone drops a dish, the next time your child spills his grape juice over your white carpet, repeat after me: “A practiced calm serves me well.” It really does. You will be surprised how this can change your behavior. With each passing event, I think you will notice you react with a little less anger, frustration, or whatever else that vexed you. Before you know it, your friends will think of you as the one with ice water in your veins.

Do things for a reason

So we’ve covered a lot of don’ts – don’t be an ape, don’t get smart, don’t get busy, and don’t panic.

Our training is designed to train the ape out of us.

Our Standard Operating Procedures are designed to help us avoid getting smart.

Our experience should help us avoid getting busy.

And I’ve given a few pointers on how to train the panic out of you.

In a way, those are all negatives. Don’ts. How about a positive do?

Do things for a reason.

Any mechanics here with experience on the GIV and the GV series? Forgive me if I get some of the details here wrong, this happened over ten years ago. We had one of the first GIVs and our mechanic had been with the airplane since day one. You may have heard that one of the test GIVs got a wing strike during V2 tests; that was our airplane. This mechanic was very good and had that GIV memorized from nose to tail. It used to unnerve me how he would do things without looking at the manual first, but he never made mistakes.

When we traded that airplane in for a G450, things went on as before, but his troubleshooting wasn’t as quick. Early on we had a problem with the hydraulic quantity on the left system going down by a lot after takeoff, then slowly coming back to normal over the course of three or four hours. “Air in the system!” he said. That jived with my experience. He bled the system, but the problem persisted. So he did it again, and again it didn’t help. Back then he was solo, we didn’t have a second mechanic. So I volunteered to be his assistant, told him I wanted to be a Gulfstream mechanic when I grow up. So I followed him out to the airplane for try number three. I noticed right away he didn’t have any manuals. He said he had the procedure memorized. I asked him if it would be okay if I followed along with the maintenance manual and he told me that would be fine.

I followed along and immediately noticed a problem. The procedure said the landing gear doors need to be down, and they were up instead. I pointed this out and he told me the hydraulic system on the G450 was identical to the GIV. We both knew that wasn’t true. So he agreed to do the bleed with the doors open. And that fixed our problem.

He was an excellent mechanic, but maybe a little lazy. I say do things for a reason, make it a good reason. Just because you’ve always done it a certain way is a reason. But there might be better ways out there. Do things for a reason, and make it a good reason.

So there you have it, 48 years of flying wisdom, or what I hope is wisdom.

Don’t be an ape.

Don’t get smart.

Don’t get busy.

Don’t panic.

Do things for a reason.