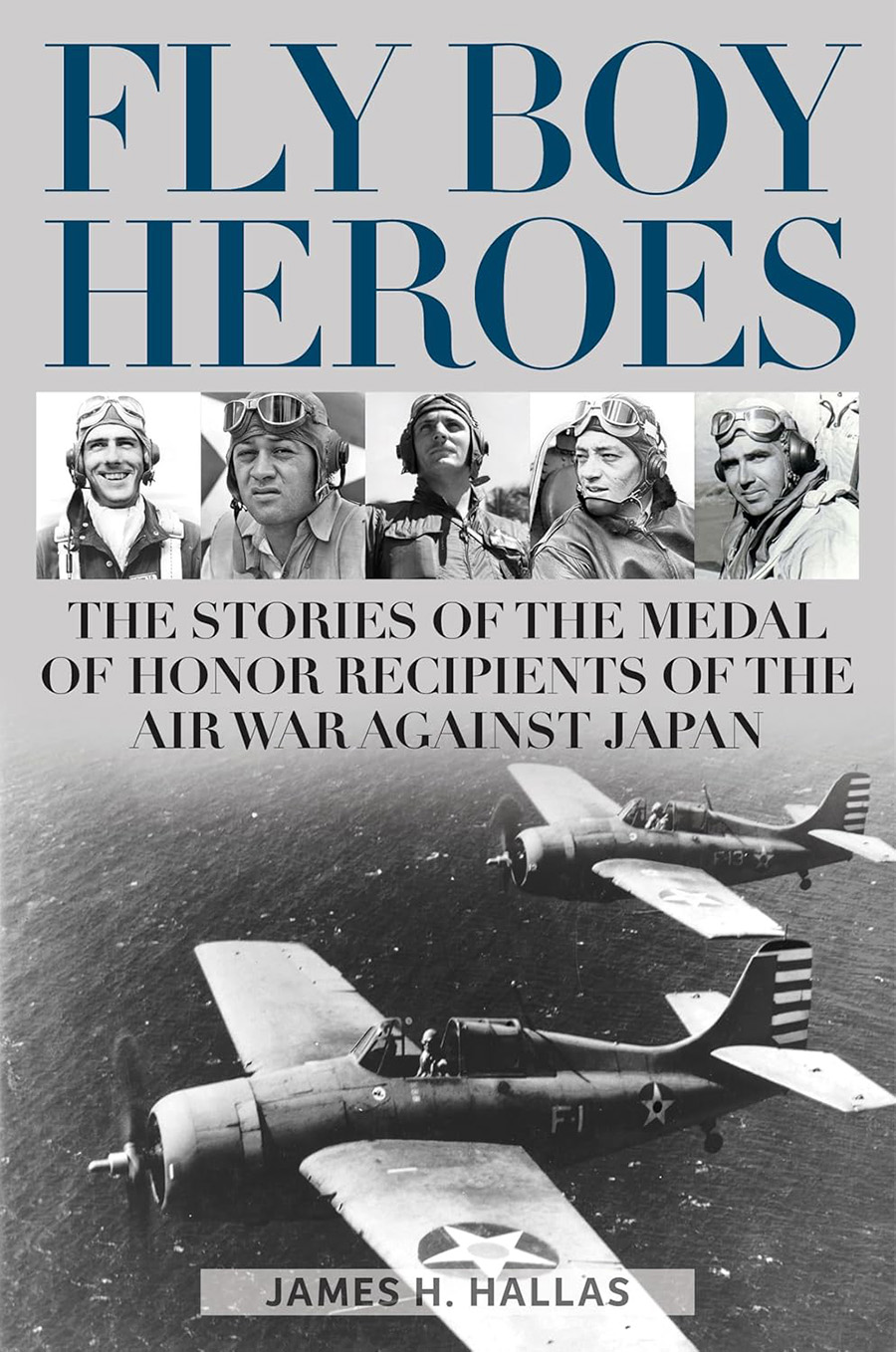

Fly Boy Heroes by James H. Hallas is more than just “the stories of the Medal of Honor Recipients of the Air War Against Japan,” as stated in the book’s subtitle. It is a study of the character of a generation of men who placed duty over self and pushed themselves beyond what even they thought possible. Hallas tells the account of 26 of the “Fly Boys” with a narrative that places you on scene, often with a flashback of life leading to that point and for those who survived, a short story of where they ended up after the war. Not all the fly boys were pilots, and many survived ordeals you probably never heard before.

— James Albright

Updated:

2025-03-10

Take, for example, the case of AOCM John W. Finn, stationed at Kaneohe Naval Air Station, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941. An AOCM is an Aviation Ordnanceman Master Chief. Finn was assigned to Patrol Squadron 14 (VP-14), responsible for the weapons on twin engine PBY amphibious flying boats. He woke to the sound of aircraft not flying where they normally flew. Driving to the Air Station, he spotted a Japanese aircraft, with the characteristic red “meat ball” symbol. The story then takes us back to Finn’s childhood, where he “had a mechanical bent, but he hated school.” He joined the Navy and knew he made the right decision after his first meal at boot camp: roast beef and gravy. Fifteen years later, he was arriving at Kaneohe where several of his PBYs were burning. He found a .30 caliber machine gun mounted on a tripod. “All I did was shoot at every one I could. You don’t knock ‘em down out of the air. That plane is going close to 200 knots, just a flick and he’s gone. You might not get fifteen or twenty seconds – that’s a long blast.” He ran between guns and helped his squadron mates clear jams, fix more guns to whatever they could find as mounts, and continued to fire with whatever machine gun he could find. When the last Type 0 fighter had finally left, he discovered that his chest was covered in shrapnel, he had been shot in the left arm and left foot. He thought the battle had lasted only fifteen minutes. He had been at it for more than two hours. His squadron suffered nine killed and four wounded. As Finn was being treated at the medical dispensary, he noticed more seriously wounded men were arriving. Finn left untreated and went home to have his wife patch him up. “It wasn’t my day to die.” The next year, Admiral Chester Nimitz presented Finn and fourteen others the Medal of Honor for their actions that day. Finn died at the age of 100 in 2010, the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from the attack on Pearl Harbor. “Personally, I did no more than my shipmates,” he insisted. ‘That damned hero stuff is a bunch of crap, I guess. . . . You gotta understand that there’s all kinds of heroes, but they never get a chance to be in a hero’s position.”

Most of the stories, as you would expect, are about pilots. Many of these, like that of Captain Joe Foss of Guadalcanal fame, are of fighter pilots you’ve heard of. Foss was awarded the Medal of Honor in recognition of his “cumulative achievement” after downing 26 enemy aircraft. You may not have known that Foss’s career was nearly ended when a new commanding general, believing airfield defense no longer necessary, ordered all aircraft be sent away on offensive operations. Foss withheld eight aircraft, causing the general to “hit the roof.” Foss’s decision was vindicated the next day when a large fleet of Japanese aircraft attacked but were stopped by the reserved aircraft.

There are many other compelling stories of aviators of all kinds. Major Gregory Boyington, of “Black Sheep” fame, said famously, “Just name a hero and I’ll prove he’s a bum.” Perhaps there was at least one bum in the mix. Boyington served as the technical advisor to the television series about his exploits. His squadron mates condemned the series as complete fiction. Boyington explained himself by saying, “I only did it for the money.” He had a troubled past, during, and after. But he was a superb pilot in a dogfight.

One of my favorite Medal of Honor stories in the book was the penultimate, that of Captain William A. Shomo. Shomo was a mortician before the war and was sent to the Philippines to fly P-39 Aircobras on photographic reconnaissance missions. The older aircraft was replaced by long-range P-51 Mustangs equipped with cameras and guns. He was sent out in a Mustang to photograph Japanese-held Tuguegarao, Atarri and Loag airstrips on Luzon, five-hundred miles from their base at Henderson Field. Flying low, “right on the deck, which was our normal method of operation,” he spotted a formation of Japanese aircraft. He pulled behind them to find twelve Ki-61 Tonys (fighters) and a single Nakajima Ki-44 Tojo (bomber). Though outnumbered six to one, he and his wingman approached quickly. To their surprise, some of the fighters waggled their wings, the sign to join the formation. The P-51s were new to the Pacific and from a distance presented a profile similar to the Tonys. Shomo sent seven of the Tonys to the water and his wingman added three more. He was awarded the Medal of Honor and became a public relations hero. He was too valuable to risk in combat and was reassigned. Years later, he told his son that the Medal of Honor was “like a millstone around his neck” because “they wouldn’t let him fly.”

Many of the stories have surprises and none disappoint. Fly Boy Heroes is an easy book to pick up, read a story, put down for a while, then pick up again. The Medal of Honor was sometimes awarded for a singular act or sometimes for many acts. Recipients quite often showed uncommon bravery against impossible odds. Or sometimes as many of them claimed, they were just doing their jobs, and the military or civilian leadership needed a morale boost for those back home. Whatever the reason, each story is worth reading.