How does a 28-year-old pilot approach crew leadership for the first time? I was based in Hawaii flying for a VIP unit tasked with supporting the U.S. Navy at several of its bases spread throughout the Pacific. In our EC-135J, the crew consisted of a flight crew of 4, a communications team of 4, a security team of 3, a crew chief and two assistants, and 1 flight attendant. That’s where I found myself in 1984, scheduled to fly off to Japan and other parts of Asia with a crew of 15 and a load of passengers. It would be one of many trips to follow. But this was the first.

— James Albright

Updated:

2018-04-20

I did have an unfair advantage on my road to learning crew leadership; I had the world’s best sensei. No, he wasn’t Japanese (like me). But he was prone to speaking to me in Japanese terms and as my sensei, my teacher, he was always willing to instruct. Captain Nicholas “Call me The Nick” Davenport knew more about how to treat a crew than anyone I knew. You can read about the flying part of that mentorship in Chapter Five of Flight Lessons 2: Advanced Flight, “Lefty.” That chapter ends with this:

“Young James-san is now samurai.”

But that was just the flying part. Here comes the part about leading. The Nick gave me a four-step process for growth as a leader. These steps appear similar (but different) than John Maxwell’s “The 5 Levels of Leadership,” which was first published in 2011, nearly 30 years after I met The Nick. I’ll quote from that book liberally in the end notes, which should make clear that The Nick was ahead of his time . . .

Our story

Prelude — The Nick’s four steps to becoming a true leader

Step 1 — Job title (because they have to)

Step 2 — Operational advantage (because you get it done)

Step 3 — Personal growth (because they see you as a mentor)

Step 4 — Loyalty (because they want to)

Also

Prelude

The Nick’s four steps to becoming a true leader

1984

The Nick sat back in his chair, thinking those The Nick thoughts that only The Nick would have. I waited patiently, knowing the time spent would be worth it. “You are now an aircraft commander,” he said. “You are the big cheese, the man in charge, the leader of the pack.” He let that settle. “But, grasshopper, what is leadership?”

I formed my answer but he stopped me. “Give me the definition without using the word ‘leader.’”

I sat and thought some more. I would have many formal leadership schools in my future, but at this point I was a novice, limited in experience. “It is the act of compelling, motivating, and influencing others to accomplish your goals,” I said.

“Very good,” he said. “Do you have the tools you need to do that?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “I am about to find out.”

“Indeed you are,” he said. “I see in young James-san the capability to be a great leader. But you are in a vulnerable period. One wrong turn and my efforts will be wasted. So let’s do this the right way. There are four steps, there is a hidden secret with each step, and you have to realize everything on your own. The only hint I can give you is about step one. Ready?”

“Or you could just tell me everything right now,” I said. “That would make life so much easier.”

“Patience,” he said. “As you assume command of Crew Five, why should members of that crew listen to you at all?”

“Because they have to,” I said.

“Yes, grasshopper.” The Nick appeared pleased with me at this, the very beginning of my leadership trek. “Step one has to do with the title the organization has bestowed upon your scrawny little shoulders and that means everyone under your command has to do what you say. But there are limits to this and there are disadvantages. But these are things you must find out on your own. Teach more, I shall not. Off with you, young grasshopper.”

Step 1

Job title (because they have to)

Stepping into the squadron ready room as the aircraft commander on a West Pacific trip for the first time induced a gaggle of butterflies into my stomach that was only made worse as the 14 faces all turned to look at me enter. A hush fell over the room. I sat at the head of the table and pulled out the pre-mission checklist. “This is trip 1984 dash 31 with Crew Five,” I read. “We are doing the standard Pacific run with a slight change in order, Tokyo first, then Osan, then Okinawa. The Philippines stop has been canceled.”

There was a collective groan and the three mechanics made the standard lewd mechanic jokes. I gave them a few seconds and continued. “Navigator, please give us the routing information and any State Department warnings you know about.”

As the navigator spoke a sense of routine started to settle. I’ve been through this before. As I had heard sometime before, butterflies in your stomach are to be expected. You need only to have those butterflies fly in formation.

The routine continued throughout the briefing, the bus ride to the airplane, the preflight, and even the flight to Tokyo. Everything, in fact, was perfectly normal. Even the flight engineer, Technical Sergeant Barlow, played his part by getting into a fist fight in the Non-Commissioned Officer’s bar. The base police allowed me to sign for him and I restricted him to his quarters at each base for the remainder of the trip.

“That’s not fair,” he said.

“The alternative is to leave you in jail here, call back to the squadron for a replacement engineer, and then talk about taking a few of your stripes.” He looked at me, speechless. “Your choice,” I said.

“Okay,” he said. “Sir.”

The rest of the trip was a blur. “Barlow is bad mouthing you big time,” the copilot reported. “He says he’s going to get off the crew as soon as we get back.”

“Good,” I said.

We got back to Hawaii and the reports from our passengers were filled with praise and we even got an “atta boy” letter from our senior passenger for a trip without any of the usual hysterics. Barlow pleaded for a crew change but none of the other crew commanders would have him. Two months later he got another drunk and disorderly arrest at our home base. I left him in his jail cell for the night and took two of his stripes. He was furious. I am sure the loss in pay hurt; maybe that would mean less beer and maybe that would mean fewer episodes of drunk and disorderly.

Barlow finally settled down and I managed a few trips without any added drama at all. Now whenever a decision was to be made, all eyes turned naturally to me. I was starting to think of myself as the crew’s leader and realized nobody remembered me as a copilot.

Six months after my upgrade to the left seat, I got a visit from my sensei. “What have you learned about the first step?” The Nick asked.

“Followers tend to follow, because they have to,” I said. “But it isn’t immediately apparent to all who the leader is and you have to convey that with your actions.”

“Why can’t you just announce, ‘I am the leader, follow me?’” he asked.

“I suppose you could,” I said. “But actions speak louder than words.”

“Very good,” The Nick said. “I shall watch your continued progress with great interest.”

Step 2

Operational advantage (because you get it done)

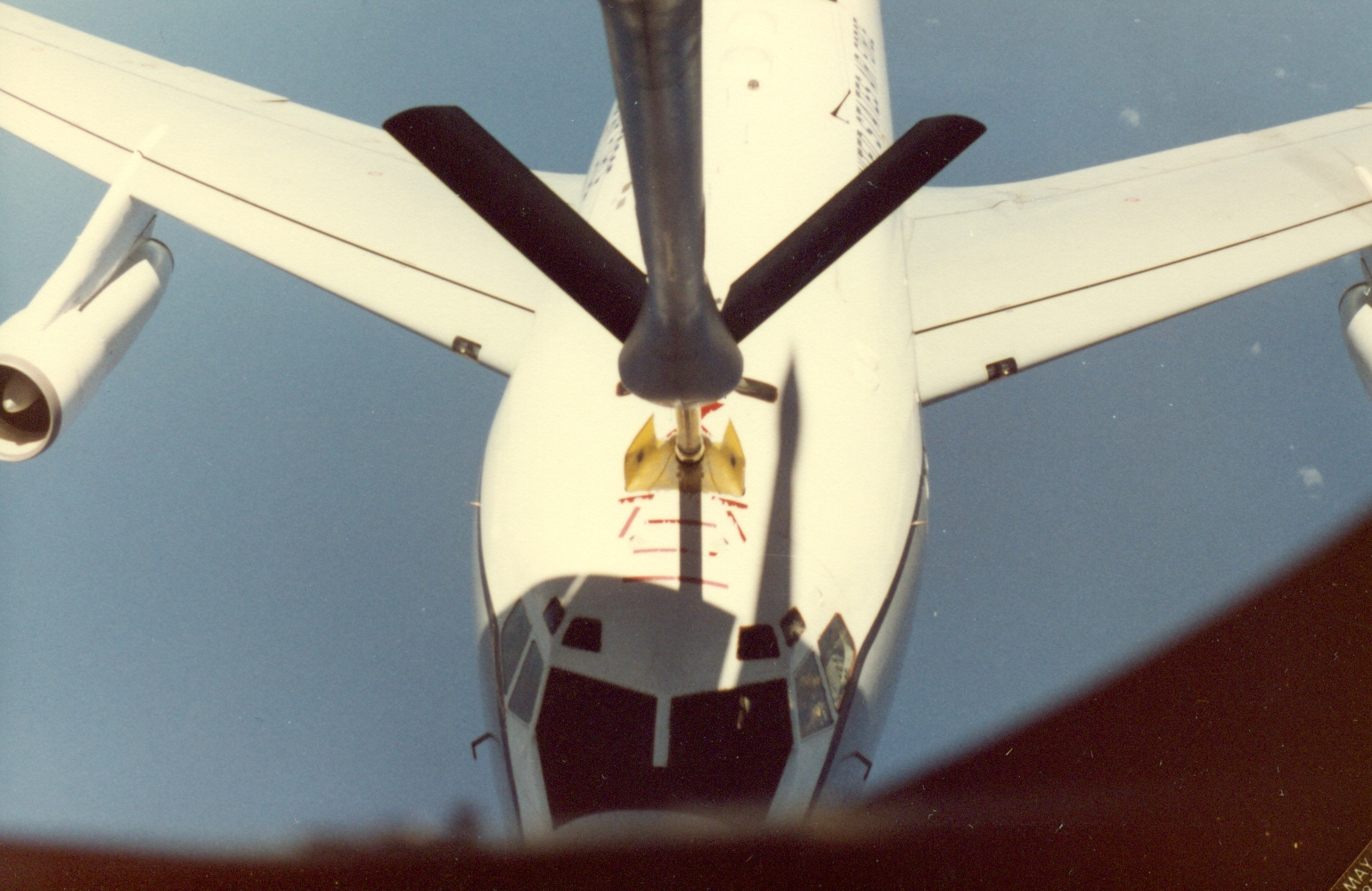

As the months raced on and trips accumulated in my thin logbook, the routine became routine. My next leadership revelation came not from my crew, but as the guest aircraft commander on another. Captain Bernie Palmer was on leave and I had his crew on a trip to the West Coast of the United States. We sat in the chocks as the crew chief gave us the bad news.

“The number four generator is shot,” he said while holding the minimum equipment list. “We don’t have any on base and the book says you are only allowed one flight to the point of first repair.” The chief of maintenance, a major, stood by his side, nodding his head. My cockpit crew, three captains and a sergeant, stood opposite. All eyes were on me.

“We are headed for Travis Air Force Base,” I said. “They have C-141s there with the same model engine. Call ahead to see if they have the needed generator. If so, we’ll call this the one flight to the point of first repair.”

“Can you do that?” The major asked.

“If they have the part I can,” I said.

The major talked into his walkie-talkie and five minutes later we had our flight release. We took off an hour later.

The squadron was evenly divided on my decision and the meaning of “flight to the point of first repair.” Most of the pilots thought it a brilliant idea, well within the letter of the regulation. The squadron commander, behind closed doors, said it was a reckless act and said he would have to consider removing me from the crew. The next day the Navy Admiral in charge of our operational tasking sent him a letter saying my resourcefulness was to be commended. The squadron commander added his signature to the letter and I inserted the letters of commendation in each crewmember’s file.

Three months later, the highest profile VIP our squadron had ever flown was scheduled on what had to be the most demanding trip. It would be two weeks on the road through parts of Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore; no one in the squadron had ever been to even one of the destinations. Many of our aircraft commanders starting politicking for the trip but I stayed out of the fray, realizing the squadron commander would never pick Crew Five. The day before his decision was due it was made moot. The Navy Admiral requested me by name.

The trip went well. Even the flight engineer managed to stay out of trouble in the temptation-rich Bangkok environment and Crew Five earned yet another commendation letter from our Navy passengers. It was to be my last trip as the crew’s commander, however. I was sent to the Air Force Flight Safety Officer Course and three months later was moved from the squadron to the wing as the base flight safety officer.

On Day One in the new office my favorite sensei dropped by to pay a visit. “I got to fly as the guest aircraft commander on your old crew,” he said. “I spent an entire month with them, in fact. They speak very highly of you.”

“That’s good,” I said. “They are a good bunch of men and women.”

“They were happy about your job promotion,” The Nick continued. “But they were sorry to see you go. Can you guess why?”

“My good looks?” I guessed.

“No,” he said. “They aren’t blind. No, it was because you always got the job done. Under their new aircraft commander they’ve already blown two trips. Your flight attendant was saying you always kept the passengers happy and happy passengers make for happy trips.”

“I suppose that’s true,” I said.

“So you have lesson two now,” The Nick said. “Your leadership abilities are improved when you can deliver operationally. What is the hidden secret of that lesson?”

I thought for a minute. When I first took command as a leader, followers followed because they had no choice. Because I said so. It would seem that when the crew understood their leader could deliver the goods, they started to follow for other reasons.

“As a leader, your words are important,” I said. “But a good reputation speaks even louder.”

“James-san has mastered Lesson Two,” The Nick said. “Two more to go.”

Step 3

Personal growth (because they see you as a mentor)

As the wing’s flight safety officer I was in charge of a program, not people. I thought perhaps my journey through The Nick’s four-step leadership program would be on hold for a while. But I still managed to fly a trip every month and eventually upgraded to instructor pilot. We didn’t have any simulators and all of our training was done in the aircraft.

I was in the squadron ready room preparing for a training sortie when the aircraft commander for the weekly West Pacific trip entered the room and headed right for me. Captain Lee Mildenhall was older and more experienced than me, but suffered from an inability to make decisions. He often looked to other pilots for reassurance.

“James, can you come look at something with me?” He asked. I followed him out the door onto the flight line. “I’ve got the smell of fuel under the airplane,” he said. “The squadron commander says that’s normal because that’s where the center fuel tank is. But I’ve never smelled fuel from that area before.”

Our aircraft had a trailing wire antenna that was little more than a quarter-inch copper cable on a reel that was pulled out by a large drogue and retracted by a hydraulic motor. The antenna assembly did indeed sit right underneath the center fuel tank. I wiped my hand on the antenna drogue and felt JP-4 aviation jet fuel.

“This is wrong,” I said. “They power up this antenna and the airplane will cease to exist.”

“That’s what Jon said,” he said.

“Who’s Jon?” I asked.

“My copilot,” he said.

“He sounds like a smart guy,” I said. “You should listen to him.”

“But the squadron commander says I have to take it because the passengers are due in about an hour.”

“Do you want to die?” I asked.

“No,” he said. “But he’s the squadron commander and he gave me an order.”

I looked at Mildenhall and wondered if he could really be that dumb. “Walk away,” I said. “I’ll take care of it.”

He returned to the squadron and I found the airplane’s crew chief. “I’m the wing flight safety officer,” I said. “I need you to open up the trailing wire antenna assembly.”

The crew chief looked at me, the two silver bars on each of my shoulders, and shrugged his own shoulders. He pulled a flat-head screwdriver from his pocket and knelt down to open the five fasteners on the antenna assembly. As he popped the last fastener the assembly cover fell open and the crew chief was immersed in fuel, several gallons of it.

“Son of a!” he yelled, running away.

I ran to the nearest maintenance van. “Get the fire department here!” I yelled.

In a few minutes fire trucks and a hazardous spill team surrounded the airplane. The crew chief was okay. The trip, of course, was canceled. That afternoon I returned to my office to find a visitor.”

“I’m Jon Patrick,” he said. “Can we talk for a few minutes?”

Captain Patrick was worried he was stagnating as Mildenhall’s copilot and was frustrated at the routine of his life in the squadron. “I don’t see how I can get ahead, doing the same thing over and over again. I don’t mind all the time off for the beach and golf. But there has to be more to life as an Air Force pilot.”

“There is,” I said. “What interests you?”

Jon explained he was an “airplane nut” from an early age but really didn’t have a mechanical or aeronautical background. “Art major,” he explained. But he would like to learn his airplane better and to eventually upgrade to the left seat.

“Why don’t you apply your artistic talents in a way that can benefit the rest of us,” I said. “We have a really lousy flight manual and if you could redraw some of the schematics with plain English explanations, our instructors would have another tool in the arsenal. In fact, you don’t need to be an instructor to instruct. You could be our squadron systems guru.”

Jon took off with a new purpose in life and we soon had beautiful diagrams to replace the laughable stick diagrams in our Air Force technical orders. While Jon remained reluctant to get up in front of a class to teach, he often led informal training sessions attended by most of our pilots. He was becoming an instructor without knowing it.

By this time, The Nick had moved over to the wing standardization and evaluation branch and spent less and less time in the squadron. He did manage to make one of Jon Patrick’s training classes. Before the class he cornered me about the now infamous fuel spill incident.

“I am hearing more about your exploits as a leader now than when you were actually a crew commander,” he said. “Why is that, James-san? Why do some people seem to want to follow you, even though you are not their formal leader?”

“I suppose some people are natural followers, and others aren’t,” I said. “Mildenhall seems to have a decision-deficit disorder.”

The Nick laughed. “There is more to it than that,” he said. “But we have a class to attend. I am pretty impressed that a squadron copilot has the nerve to teach us old farts.”

“Me too,” I agreed.

The class was great. Jon Patrick’s drawings helped explain things we didn’t know and the discussions that followed got us all thinking. When he was done, The Nick assumed the role as the senior pilot and heaped buckets of praise on our young instructor.

“I owe it all to James,” Patrick said. “If it wasn’t for him pushing me, I would be on the golf course right now knowing less about the airplane and wondering about my place in the squadron.”

The Nick invited me to the golf course snack bar for a burrito and more sensei talk. “Lesson Three, grasshopper,” he said. “You no longer have a leadership title, and yet you lead. I hear this from many people in the squadron; and not just pilots. What is this part of leadership you have discovered?”

I knew the term he was looking for, but I had never connected it with leadership. But it fit. “Mentorship,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “You are providing them an opportunity for personal growth. And when you do that, you enhance your own. But now that you have achieved Step Three on our journey to becoming a true leader, why didn’t that work with our problem aircraft commander? Why were you unable to inspire Mildenhall to act and instead had to push your weight around as the chief of flight safety? That’s all the way back to Step One, after all.”

“Patrick was open to mentorship,” I said. “He had the motivation and I suppose he was willing to look to me as a mentor. But to Mildenhall I was just another aircraft commander, a peer. I had to revert to Step One with him.”

“Ah so,” The Nick said. “You have truly achieved Step Three. Always remember that with each relationship, you have to reevaluate your leadership techniques. There are times your reputation, young James-san, will precede you and you can jump to whatever level you desire. But you may need to fall back to lower levels depending the follower or the situation.”

Step 4

Loyalty (because they want to)

Northwest Airlines soon snapped The Nick away from us and I found myself without my most valued mentor. Just as I was becoming comfortable as an instructor pilot I was stunned to find myself in The Nick’s former position, as the wing’s chief of standardization and evaluation.

At first, most of my time was taken administering check rides to squadron pilots and overseeing the efforts of our many evaluators in other crew positions. We had the lead crewmember in each position in our EC-135J (Boeing 707) squadron as well as the T-33 single engine jet used as a training bird and for dissimilar combat training for the local Air National Guard unit. These were becoming suddenly contentious as the experience level in both squadrons was falling and our check results betrayed a lack of proper training.

“Two angry phone calls,” my secretary said as I walked in after a week on the road. “Colonel Spindler says we overstepped our bounds by busting his favorite navigator and Major Compton wants Sergeant Lombard’s head on a pike for busting three radio operators in a row.”

“Let me see Giffords and Lombard as soon as possible,” I said. “And let me see those flight evaluations too.”

The flight evaluations were iron clad as were the conduct of all four checks. Major Carl Giffords outranked me, but as my navigator he worked for me. I had asked him to tone down one of his evaluations early on after he admitted to being overzealous. But that was over a year ago.

“If I hadn’t intervened, he would have blown the rendezvous and we would have lost the tanker,” he said while pointing to the busted navigator’s log.

“That’s about as clear as a bust can be,” I said.

Master Sergeant Billy Lombard’s busts were even tighter but he seemed more willing to give. “If you want me to change them, I will, sir.”

“Were these radio operators up to the training standard set by the squadron?” I asked.

“No, sir,” he said.

“If the squadron sent them on the road without instructors, could they do the job?”

“No, sir,” he said.

“The bust stands,” I said.

“The squadron says they are going to replace me and you both, sir.”

“I would rather be replaced than turn someone loose on the world who isn’t ready,” I said. “How about you, Billy?”

“I’m good with that, sir,” he said. “Thanks for having my back, sir.”

The squadron was unhappy; but the blowback wasn’t nearly as bad as Lombard predicted. Lieutenant Colonel Spindler, the squadron commander, had a reputation for histrionics. But he could calm down after a day. All four busted crewmembers were retrained and managed to pass their rechecks.

We tended to issue passing grades on a vast majority of all administered check rides; the rate hovered right around ninety percent. Of the busts, fully half became contested and required a visit to the offended training office. But I never changed a single check ride result. After a few months, the squadron stopped contesting busts.

But as the year drew to a close, our focus shifted. The entire wing became consumed with preparation for a biennial command headquarters inspection. Half of that grade would depend on how well my office did and half of our grade depended on our paperwork.

“They will focus on flight evaluation forms,” Master Sergeant Billy Lombard said. “We did this two years ago and the inspectors were in here every day reading every flight evaluation form we had written in the last two years. We should each reread every flight evaluation form in our specialties.”

“We’ve been doing that throughout,” Major Carl Giffords said. “I think we should focus on the quality of our written tests.”

“And don’t forget the quarterly progress reports and publications,” another voice offered.

“What about personnel reports?” our secretary asked.

“None of that matters,” Sergeant Lombard said. “Those are a very small part of the inspection. We have to focus on flight evaluation forms!”

I listened to all the suggestions, the protests, and the counter-suggestions. “We have two months to prepare,” I said. “Here’s my view.” I explained that reading a flight evaluation form over and over again was unlikely to yield anything new; I would assign each member of our staff to inspect the flight evaluation forms written by another person. We would all spend the next week in the effort. “The navigator will evaluate pilot forms, the pilot will inspect radio operator forms, and so on. That puts fresh eyes on old paperwork. But that’s not all.”

I went on to say Giffords and I would spend two weeks studying the regulations and come up with our own inspection checklists while each program administrator would prepare for our pre-inspection. Then, in a week, we would inspect the written tests, quarterly reports, and publications programs with the idea of being hypercritical. That would give the owner of each program a month to address our mock findings before the real inspection.

“That’s a lot of work!” Lombard said. “But I think we can do it.” The rest of the crew agreed and we got to it.

The fresh eyes on the flight evaluation forms yielded multiple hits on everyone’s paperwork, including my own. “You got the training dates wrong on this one,” Lombard explained. “It was an easy mistake to make, since adding ninety days in January gets fouled up with the odd number of days in February.”

“Nice catch, Billy!” I said. “You can bet the headquarters inspector would have fried my behind with that. I owe you!”

The two weeks going over the regulations used by the inspectors taught me more about the inspection process than I knew before and helped Giffords and me to be ruthless in our mock inspection. As quick as we found discrepancies the office got to work making fixes. “The guys are putting in a lot of late nights,” Giffords said. “I noticed you never asked for that, but they are doing it.”

“They want to do well,” I said. “We all do.”

Finally the two-week visit from headquarters came. Their inspection seemed tame by comparison, but the inspectors held their results close to their vests. We were left to guess our fates.

The wing gathered in the base theater, the only venue large enough for every squadron and wing section. The inspectors revealed mostly passing grades for each squadron and subordinate unit. They saved our standardization and evaluation office results for last. The wing commander looked at me anxiously, knowing his wing’s only chance of an “exceptional” result depended on my office getting an unprecedented “exceptional” grade.

“And finally, we come to wing stan/eval,” the inspector on stage said. The first slide showed the results of the check rides the headquarters staff had administered to three crews: my Boeing 707 flight crew and two T-33 crews. Since we had four crewmembers to the single pilot T-33, there were six grades. “Four exceptional, two satisfactory,” the speaker said. The four exceptional grades belonged to us in the big bird. “Overall grade,” he continued, “exceptional.” The audience cheered.

“Wing standardization and evaluation administration is next,” the speaker continued. A single slide appeared with a sheet of paper covering the bottom. The slide operator pulled the paper lower with each announced grade. “Flight evaluations: exceptional.” The audience murmured, my staff smiled. “Written examinations: exceptional.” The murmurs became excited. “Publications: exceptional.” A muffled cheer; there was one more grade for standardization and evaluation to come. “And finally, personnel reports were also exceptional.”

Now there was applause but that quickly subsided as the final slide of the day appeared; once again the bottom result was covered. “The overall grade for the Hickam Air Force Base Wing is,” the lead inspector said with a pause for flourish. “Exceptional.”

Now the cheers were uncontained. The wing commander walked over to shake my hand and that of everyone on our staff. It was a nice way to end my tour in Hawaii; I had just received orders to report to the Air Force’s only Boeing 747 squadron. My farewell party was a “must attend” event for much of the wing.

I was happy to see visiting airline pilot, Mister The Nick for the big event. “Grasshopper did good,” he said.

“The entire standardization and evaluation office did good,” I said.

“I heard everyone put in a lot of hours,” he said. “I was surprised to hear you even got Billy Lombard to chip in.”

“I think he put in the most overtime,” I said.

“I get the feeling there isn't anything your guys wouldn't do for you. And that leads us up to the fourth and final step in your journey to true leadership,” he said. “Why did your followers follow your leadership?” he asked.

“Because they wanted to,” I said.

“Yes,” The Nick said. “Loyalty is rare. But once you earn it, it is a powerful ally.”

“That is a good lesson,” I said.

“But there is a final hidden secret,” he said. “You have mastered the four steps of true leadership. You can lead by virtue of the job title the organization bestows on you. You can lead because you know how to get the job done and that generates followers. You can lead because you are a natural born mentor. And now you can lead because you generate loyal followers. So how will that transfer to the next job, grasshopper?”

“I suspect it won’t,” I said. “I will have to start all over again. But now that I know how, it will happen faster and more easily.”

“You have learned all that I can teach you on this subject,” The Nick said. “It is time we part ways. Good luck to you, grasshopper.”

End notes

From John Maxwell

From Step 1 - Job 1itle

Position is the lowest level of leadership — the entry level. The only influence a positional leader has is that which comes with the job title. People follow because they have to. Positional leadership is based on the rights granted by position and title. Nothing is wrong with having a leadership position. Everything is wrong with using position to get people to follow.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 7

You can have a leadership position; but that doesn't make you a leader.

There's nothing wrong with having a position of leadership. When a person receives a leadership position, it's usually because someone in authority saw talent and potential in that person. And with that title and position come some rights and a degree of authority to lead others.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 39

But even more importantly, with that title comes the opportunity to grow as a leader.

From Step 2 Operational advantage

"If you think you're leading but no one is following then you are only taking a walk."

Source: C.W. Perry. Maxwell, pg. 18

It is easy to spot a leader who relies on position and nothing else . . .

People who rely on position for their leadership almost always place a very high value on holding on to their position—often above everything else they do. Their position is more important than the work they do, the value they add to their subordinates, or their contribution to the organization.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 52

When leaders value position over ability to influence others, the environment of the organization usually becomes very political.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 53

Positional leaders receive people's least, not their best. [ . . . ] Clock watchers. [ . . . ] Just-enough employees. [ . . . ] The mentally absent.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 63

On the production level leaders gain influence and credibility, and people begin to follow them because of what they have done for the organization.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 8

People intrinsically want to get the job done and know that leaders with a track record of satisfying organizational needs will make life easier for everyone. An organization with a track record of success makes everyone's job easier, not just the leader's.

Production qualifies and separates true leaders from people who merely occupy leadership positions. Good leaders always make things happen. They get results.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 133

It is hard to fake results. In the military we sometimes had inept leaders carried along by very efficient staffs but that rarely lasted very long. These fakers are eventually caught.

"There are two types of people in the business community: those who produce results and those that give you reasons why they didn't." —Peter Drucker

Source: Maxwell, pg. 135

The primary side effect of results is credibility. And that gets noticed both up and down the chain.

From Step 3 - Personal growth

Leaders become great, not because of their power, but because of their ability to empower others. [ . . . ] They use their position, relationships, and productivity to invest in their followers and develop them until those followers become leaders in their own right..

Source: Maxwell, pg. 9

Good leaders encourage their followers to become good leaders. The result can be infectious because the troops know which commanders have a track record of fostering the next generation of commanders.

Most of what an organization possesses goes down in value. What asset had the greatest potential for actually going up in value? People! But only if they are valued, challenged, and developed by someone capable of investing in them and helping them grow.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 172

When faced with high workloads and seemingly impossible odds, it is tempting to just put everyone to work with little thought given to training and mentoring. But this is nothing more than treading water. You should always find a way to develop subordinates into the next generation of leaders. Even if they cannot come up fast enough to help with the task at hand, knowledge that you believe that strongly in them may motivate them to work even harder.

Good leaders do not lead everyone the same way. Why? Because every person is different, and you're not on the same level of leadership with every person.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 19

From Step 4 - Loyalty

On the Permission level, people follow because they want to. When you like people and treat them like individuals who have value, you begin to develop influence with them. You develop trust. The environment becomes much more positive.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 8

Maxwell identifies this level as the second along the way to his five levels of leadership. The Nick would say this level requires a few more prerequisite steps and is the final step. I tend to agree with The Nick.

Leaders [at this level] develop relationships and win people over with interaction instead of using the power of their position. That shift in attitude creates a positive shift in the working environment. The workplace becomes more friendly. People begin to like each other. Chemistry starts to develop on the team. People no longer possess a "have to" mind-set. Instead it turns to "want to."

Source: Maxwell, pg. 87

Permission level leaders listen to their people, and their people listen to them.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 8

Building relationships takes time. It can be very slow work.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 98

But once that relationship is built, it tends to be more enduring.

What's the key to being productive? Prioritizing. To be an effective leader, you must learn to not only get a lot done, but to get a lot of the right things done. That means understanding how to prioritize time, tasks, resources, and even people. [ . . . ] Effective prioritizing begins with eliminating the things you shouldn't be doing.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 161

An easy way to spot faulty prioritizing is when you hear the phrase, "we've always done it that way." Chances are you shouldn't be doing it that way for much longer.

Another time waster is completing a "to do" list. Yes, you should write a "to do" list to get an idea of what you are facing. And you should definitely attack the top one, two, or three items. But once those critical items are done, what should you do next? You should come up with a new list.

Author and pastor Rick Warren observes, "You can impress people from a distance, but you must get close to influence them." When you do that, they can see your flaws. However, Warren notes, "The most essential quality for leadership is not perfection but credibility. People must be able to trust you.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 100

Every time you lead different people you start the process over again.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 17

Other gems . . .

Thank the people who invited you into leadership.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 78

Dedicate yourself to leadership growth.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 78

Define your leadership. Who am I? What are my values? What leadership practices do I want to put in place?

Source: Maxwell, pg. 79

Focus on the vision: One of the ways to reduce an emphasis on title or position is to focus more on the vision of the organization and to think of yourself more as someone who helps clear the way for your people to fulfill that vision.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 79

Shift from rules to relationships.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 79

Initiate contact with your team members.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 80

Don't mention your title or position.

Source: Maxwell, pg. 80

Even when introducing yourself. The impact of the title will be greater once inferred or mentioned by others.

References

(Source material)

Maxwell, John C., The 5 Levels of Leadership, 2011 © John C. Maxwell, Center Street Hachette Book Group