"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Fifteen.

— James Albright

Updated:

2012-02-27

In 1979 there was ample temptation to be pessimistic as a second lieutenant, flying a KC-135A tanker, as a copilot, at what had to be worst base in the Air Force, and while assigned to the Strategic Air Command. Nobody, we were told, respects a second lieutenant. The KC-135A is underpowered and under-equipped. The Air Force wanted desperately to close Loring Air Force Base and cut funding to the minimum. And SAC? SAC was in its death throes.

But, for some strange reason, I was looking forward to the challenges to come.

Noo Klee Ur Combat

1980

Air refueling, from the tanker’s perspective, was not too difficult once the receiver found its way to the “stabilized pre-contact” position. But getting to that point was, now and then, a problem. But that wasn’t my problem. As a fully trained KC-135A copilot, the Strategic Air Command was happy for me to execute three takeoffs and landings every 90 days, fly three instrument approaches, and pull Emergency War Order — EWO — alert. As for air refueling, I had to watch over a fuel panel, turn the pump switches on when the boom operator told me to and turn them off when the receiver disconnected or the pilot yelled at me. I could handle all of that.

Getting qualified as a tanker copilot was easy. Learning the flying mission was easy. But becoming a certified SAC trained killer meant I had to learn the secret mission and then I had to do something called "certify." It sounded ominous. I needed advanced intel.

“Colonel Burkel eats lieutenants for lunch,” I was told, “you might as well know he’s going to make a fool of you. Don’t worry about it, it happens to every second lieutenant copilot.”

I just didn’t see how that was possible. I studied every aspect of my job and thought I had every angle covered. The only new territory was the EWO stuff, the things I was expected to know if we were going to war. The standard list of copilot questions were all easily handled.

“What’s the first thing you do after takeoff?” (Install the thermal radiation curtains.)

“How often do you copy the coded message from headquarters?” (Every fifteen minutes or after a change.)

“How much fuel can you offload?” (All of it, except whatever is left in the pipes from the wing tanks to the engines.)

I had to find the most recent victim and ask. “He asked me if I could take over the navigator's duties,” my compatriot answered in hushed tones, “if he died before the rendezvous with the bomber.”

“Really?”

“Yeah,” he said, as if reliving a bad dream, “if you answer all his standard copilot questions; that’s what he’ll ask you next. You might as well get one of the easy ones wrong. It will all end sooner that way.”

“He has to prove he’s smarter than you?”

“Yeah.”

“I’ve been in SAC for a month,” I said, “this won’t be much sport for him.”

EWO certification was a two day process. The crew spent a full day studying classified manuals and learning about recent changes in world politics, all in an effort to better execute their emergency war orders. The second day was the certification. Each crewmember gave a prepared speech to the certifying official and then answered that officer's questions. The certifying official was at least a lieutenant colonel. I read each manual twice and listened to the rest of the crew predict our fates.

"We are going down in flames," the aircraft commander said. "We're scheduled to certify to the wing commander himself! He's a died in the wool bomber pilot who hates us tanker toads. He makes a point of cutting every tanker officer off at the knees just for sport."

"It's a shame," the navigator agreed, turning to face me. "You being brand new like this. Too bad you are going to fail your first certification."

"Who says we are going to fail?" I asked. "We all know our jobs. All we have to do is convey that to the wing commander."

"Even if you know your job cold," the aircraft commander said, "he'll ask you about someone else's job."

The certification was the next morning. As the copilot I probably had the smallest role in the crew when it came to doing our nuclear mission. If the wing commander asked me about how to do the aircraft commander's job I would be in trouble. The wing commander was a bomber aircraft commander and I would be playing on his turf. If he asked me about the boom operator's job, I would again be in trouble. What about the nav? I couldn’t master what the navigator spent months learning, but I knew I could at least get some of it. I picked up my air refueling manual and began with the basics.

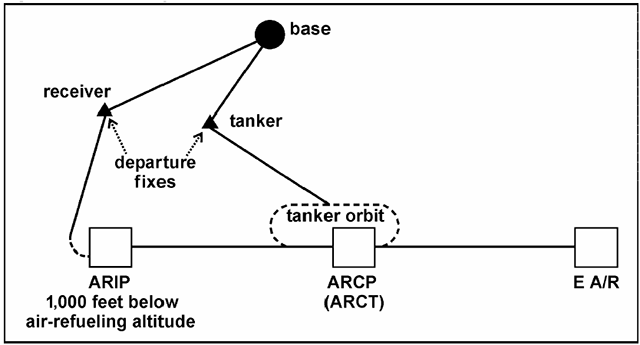

The point parallel rendezvous was the standard means of flying our KC-135 over the Air Refueling Control Point (ARCP) while waiting for the B-52 to arrive at the Air Refueling Initial Point (ARIP). Once he reported there, usually at the Air Refueling Control Time (ARCT), we would turn towards him and establish the required offset distance from his inbound track. I didn’t know the required offset, but I knew it changed with winds. Once we were at the required range, we would turn 180 degrees and roll out 3 miles ahead of him. Once again, I didn’t know what the range was, but it too could change with winds. What else? We usually flew this at 275 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS), at 25,000’ altitude, and the turns were made at 25 degrees of bank.

It seemed I had the mechanics of the process down, just not the two magic numbers: offset and turn range. It was simple aero, how hard could it be?

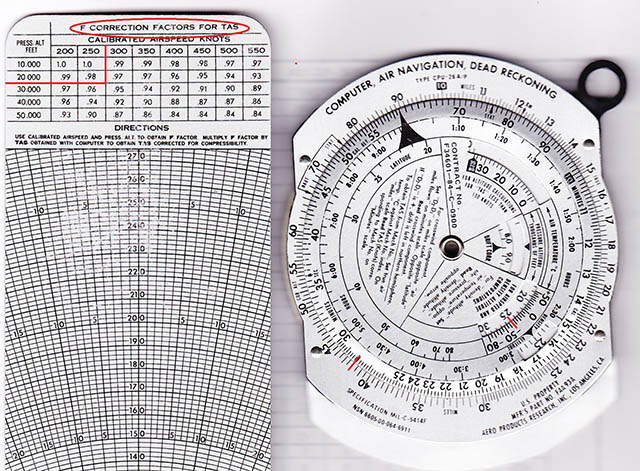

I pulled out my favorite Aero text book, by Charles Dole, and found the equation for turn radius. First I was going to need the True Airspeed (TAS) but all I had was Indicated Airspeed (IAS). Pulling out my hand dead reckoning computer — really a circular slide rule issued to all Air Force pilots back then — I knew I could convert IAS to CAS by dividing it by the appropriate F-Factor.

CAS = IAS / F = 275 / .98 = 280

Then the computer needs the temperature at 25,000 to figure the TAS. If it were a standard day, the temperature would be 15°C minus 2°C per thousand feet. So the temperature at 25,000’ would be:

T = 15 — (2)(25,000) = -35°C

Setting -35°C opposite 25,000’ in the appropriate window places the outer scale in the correct orientation to read TAS opposite CAS. Answer: 420 KTAS.

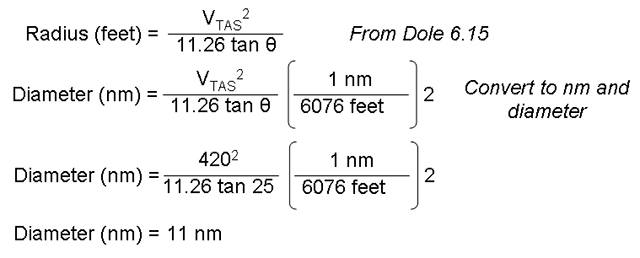

Now the turn radius equation had all it needed:

That was easy enough. But what about the turn range? The tanker and bomber had a closure rate of 840 knots! And for the tanker’s turn the closure rate wasn’t constant. No wonder the navigator was needed!

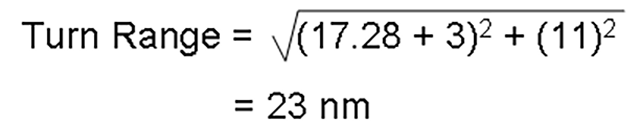

If I assumed the tanker rolls out exactly abeam where he initiated the turn, I no longer needed to consider the closure rate, only the bomber’s speed. To find out how much territory the bomber covered while the tanker was in the turn, I needed only to find out how much territory the tanker covered in his half turn, their speeds were equal. The circumference of a circle is 2πr and 2r is diameter but I only wanted half the circle. So the distance of the half circle would be πr/2, or π(11)2 = 17.28 nm.

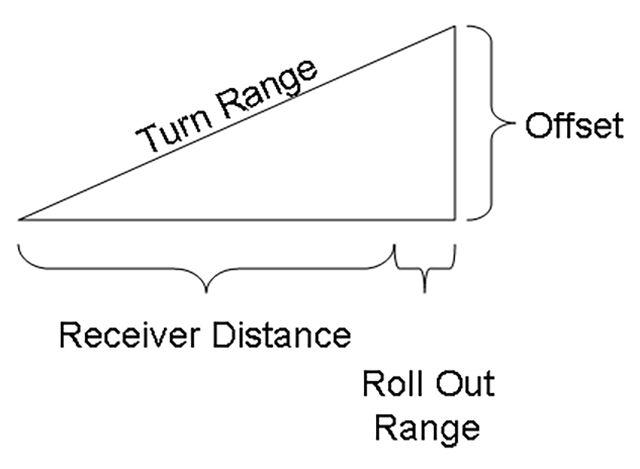

Of course this was the distance the bomber covered getting to the 3 nm roll out range. The offset range was the hypotenuse of this triangle, a larger number.

With a little help by Pythagoras, I had my answer:

So now I knew I could bluff my way through the navigator's toughest job, but what if the wing commander didn't ask me a navigator question? I had to steer him there. But how?

The next day I waited my turn. Colonel Burkel was in rare form and he had already humiliated the pilot and navigator. The pilot missed a bit of breaking news about the Soviets on the Polish border.

“You have command of one of my crews,” Burkel said, “they are looking to you to have all the answers. I am looking to you to at least have a God Damned clue about geopolitics! Do I make myself clear?”

“Yes sir,” the pilot said. I didn’t know about the Soviet-Russian geopolitical thing either.

He asked the navigator about aircraft endurance once refueling was complete. Those questions should have been sent my way.

“I’d ask the copilot,” the nav said.

“You would ask a butter bar about something you should know?”

The nav stood at attention, in silence. Our crew was going down in flames. The cost of total failure would be having to do all this fun over again next week. That after an appropriate annotation to our permanent records: “failed nuclear certification.” Nobody wanted that.

It was my turn. The pilot introduced me as “our new superstar fresh out of copilot school, a distinguished graduate!” He was doing a good job of lowering expectations until that last bit. Burkel gave me the standard copilot questions and I gave him the standard copilot answers. This was going to be easy.

“Loo ten ant,” he said while giving me a sideways glance, not bothering to pay complete attention to me standing at attention in front of a map of the Soviet Union, “lets say you get the thermal nuclear curtains installed, just the way you say you would. You pull out your standard issue flashlight to check your work and it doesn’t work. Now what?”

“The curtains don’t work?” I stammered.

“No, the flashlight!” He was yelling at me for some reason. “The thing Uncle Sam gave you on day one of pilot training and you’ve been using ever since. You click on and there’s nothing.”

Now I knew where he was headed and I obliged him, disguising my joy at what was to come.

“Sir, I would borrow the navigator’s.”

“Very good,” he said changing from anger to happiness in nothing-flat. “You look over and he’s face down on his charts in a pool of blood.”

“I would administer first aid, sir.”

“He’s dead.”

“That’s unfortunate, sir.”

“It may be unfortunate for you, but he’s dead.”

I stared into the wing commander’s eyes and said nothing, setting the trap.

“The war effort means you are going to have to take over his duties, son.” He let his words sink in. “You still have a point parallel rendezvous to perform or those bombers aren’t going to get their gas and if they don’t get their gas, my boys are going swimming and not bombing the way we promised Mother SAC they would. We can’t have that, now can we? What is the purpose of our existence here?”

“Nuclear combat,” I said, “toe-to-toe with the Rooskies.” Every B-52 pilot loves that movie.

He smiled. “Yes, so how we going to war if your navigator is dead.”

“I will move his corpse aft and I will execute his duties.”

“How the hell are you going to do that, son? You wouldn’t know how to set up a point parallel if your life depended on it.”

“I’ve seen a few,” I said, still standing at attention. “I believe I can pull one off.”

Burkel chortled with glee. “Talk me through it, boy.” Then, almost sotto voce, “this ought to be good!”

“Sir,” I began, “first I will convert our indicated airspeed to true using the indicated temperature and my CPU-26 Alpha circular slide rule. The speed tends to range from 400 to 440. With a little geometry, I can compute the required offset distance which in a no wind situation will probably be around 11 nautical miles.”

I talked for about ten minutes. He just sat there and listened. He started to look a bit dejected. When I was done talking he almost didn’t react. But then he recovered.

“Loo ten ant,” he said, “sit down. We are done here.” With that, he got up and left.

The rest of the crew just stared at me. Silently, we gathered our things, checked in our secrets, and we too left. The next day the squadron was buzzing with the play-by-play. The next week we were on alert. One year later, when I had to certify the SAC EWO mission for my second and last time, I didn’t get any questions at all.