"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Eighteen.

— James Albright

Updated:

2017-03-14

We normally associate the concept of risk as dealing with personal safety and the avoidance of danger, but there is more to it than that. We accept a measure of risk when flying airplanes because that is the nature of the business. But what about risks that don’t threaten your life, but threaten your livelihood instead? Career risk is something we all deal with, but in the military, there is an added element. You can plod along without career risk in many professions, but if you are a military officer and never find your career at risk, you are not doing your job correctly.

So, this then is a story that traces an Air Force officer’s arc in four levels of schooling: college, pilot training, “Squadron Officer’s School,” and the “Air Command and Staff College.” It spends three-quarters of the plot waxing poetic about integrity and other high ideals, but then puts all that to the test in the last quarter. Was there career risk? Certainly. Did it all work out in the end? Let’s see . . .

Risk is necessary; the turtle only makes progress when he sticks his neck out

1991

Officership

“. . . Nor Tolerate Among Us Anyone Who Does”

I grew up in a family where honesty was never discussed, it was assumed. When I showed up at Purdue University as an Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) cadet I didn’t expect any long lectures on the subject, I didn’t think they were needed.

For its part, the ROTC program touched on the subject lightly, noting that our counterparts at the Air Force Academy were required to memorize an honor code:

We will not lie, steal, or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does.

Of course that went right along with my upbringing. I would never lie, steal, or cheat. I never thought about the tolerate bit, but it had never come up either. I think our military environment was overpowered by the college environment. Most of us were engineering students and our civilian peers took this integrity issue very seriously. You didn’t want to risk being caught certainly. But even more motivating, perhaps, was the idea that we were all competing for lucrative jobs after graduation. I never saw a single incident of cheating or dishonesty during my four years at Purdue.

Cooperate and Graduate

“Comrades in Battle”

We started Air Force pilot training with 77 officers, most of us second lieutenants. Of these, all but three came from the Air Force Academy. I somehow expected these lieutenants would be cut from a finer bolt of cloth than we ROTC guys. But in our second week I found that wasn’t the case.

We started class on January 2nd, 1979, a Tuesday. We were split into two flights, my flight was called “No Loss” and started the program with 38 "studs." (We were forbidden from using the term "student.") After our Day One physical exams, we had 36 studs left to face the academics. On Friday we got our first written tests and everyone got 100 percent. I had to study very hard but it seemed effortless for many of my peers. “These guys are smart.”

I shared a table with three other second lieutenants, each a product of the Air Force Academy. By the second week, most of the class was getting something less than 100 percent on each exam, but my tablemates were keeping pace with my perfect scores. By the third week, only two of us stayed at that level and we both shared the same instructor pilot.

“And then there were two,” Marke Gibbs said, holding up his flawless exam. “I think you are going to be on your own after the aero test. It isn’t my strongest subject.”

And that is the way it turned out. But it was even worse. Four in our flight busted that test. “We got to do better as a flight,” our flight commander said. He was a captain, a former navigator, and almost 30 years old. He was “the old man.”

“Cooperate and graduate,” he said to us at a rare flight meeting. “We are all in this together and we don’t leave our comrades behind. You guys understand?”

“You bet,” we all said. I was willing to put in extra hours helping our academic stragglers. But that didn’t seem to be the plan.

“What’s seven?” I heard from behind me on our next exam.

“Don’t you CEE the answer,” someone else said.

“Anybody got fifteen?” I heard a little later.

“James,” I heard from my left. “Stop covering your paper. You're just like a school girl.”

It was Marke Gibbs, my tablemate. Marke was a good guy, great pilot, and completely honest. Or so I thought. Now I had an ethical decision to make. I would never cheat. But would I tolerate one who does? We were, after all, comrades in arms. I moved my hand.

Integrity

"Legal, Moral, Ethical

Air Force officers have varying levels of officer training schools to attend, either “by correspondence” or “in residence.” Theoretically you could receive credit through either method but since only the top five percent were selected to attend in residence, it became a game towards promotion. Everyone did the correspondence course in hope of being selected to attend in residence. The first tier of these courses was for captains and was called “Squadron Officer School,” or SOS.

Here is where I first really took notice of the officership concept of “Legal, Moral, and Ethical.” In a nutshell, it works like this. An enlisted military member follows orders of his or her officers immediately and without question because, in theory, those orders can be time critical. For example, the lieutenant orders, “Take that hill!” You take the hill, even if it means you could be killed. But for an officer, following orders is a bit more complicated. An officer must evaluate every order with three questions: Is the order legal? Is the order moral? Is the order ethical? If the answer to any of those questions is no, the order must be refused.

But there was no need for any of that at SOS. We spent most of our time in class giving speeches, writing papers, hearing lectures, and taking exams. We also spent a fair amount of time playing sports designed to test our leadership capability and in what were known as leadership labs.

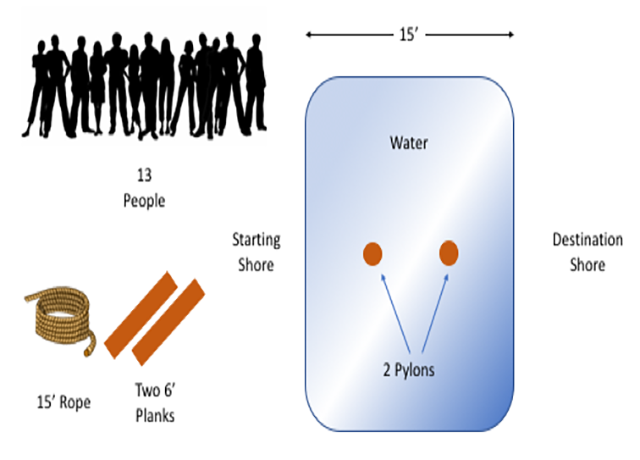

You would spend your entire time at SOS in groups of 12 or 13 students and every few weeks you would be required to show up in fatigues to “the lab” which was divided into several large cells over a pit of sand or pool of water. You could be asked, for example, to cross the sand pit given several wooden planks, rope, and maybe a few other items. The planks were never long enough to cross the obstacle on their own, of course. Each problem was tailor-made for an industrial engineer.

At our first lab we had to cross fifteen feet of water with two six-foot planks, some rope, and somehow take advantage of two vertical pylons standing at the one-third, and two-thirds point of the crossing. The wizards of smart in our group immediately set out to lash the boards together.

“That’s not going to work,” I said. “You aren’t going to be able to get the boards securely tied.”

“We got this, James,” they said.

“There’s an easier way,” I said.

“We got this.”

It was a timed exercise and each attempt of “Plan A” failed, getting several of our students soaked after falling from the poorly lashed boards. The group became dejected. With five minutes to go I had enough. I placed the first board from the shore to the first pylon and crawled to the first pylon. “Hand me the second board,” I said.

“We don’t have enough time,” someone said.

“Humor me,” I said.

“What about the rope?” someone else said.

“Throw it away,” I said. I took the second plank and placed it between the first and second pylon. I crawled to the second pylon. “Somebody take my place on the first pylon.”

A second student did so. “That’s useless,” one of the shore bound students said. “You still need to get to the opposite shore.”

“Move to the middle,” I said to the second student. She did so. “Now someone take her place on the first pylon.” A third student gamely moved. “Now hand me the first plank.” I placed the first plank between the second pylon and the shore and moved to our destination.

“Now take the first plank back to the first pylon and shore and repeat.”

Everyone understood immediately and with almost a minute to spare we were on the destination shore and shared high fives. “We” had solved our first leadership lab.

We had ten such leadership labs to accomplish and repeated the “we got this” followed by an engineer’s perspective saving the day on the next two events. Then I was formerly told to keep my mouth shut because I was inhibiting the leadership potential of my peers. We started failing more labs than passing.

With a week of SOS to go I met up with two fellow Purdue graduates who had the same tale to tell. “It’s not just a leadership school,” one of my fellow engineers said. “It’s a silly leadership school.”

SOS back then was three months long, which I would have to say was about a month too long. A few years later the Air Force decided more officers should attend so they shortened the course by a month to increase attendance by a third. A few years later they shortened it again to just a month. Now three times as many officers can attend. I hope they got rid of the silly labs.

Risk

“Sticking Your Neck Out”

The next level of schooling for an Air Force officer is called “Air Command and Staff College,” or ACSC. It was designed for majors aiming to become the next generation of leaders, either in the staff or as commanders. The promotion rate to major is between 75 and 80 percent and of those, the top 5 percent are designated to be eligible to attend ACSC in residence. Of those, just over a half attend. The college is one year long and graduation virtually guarantees promotion to lieutenant colonel. The promotion rate, service-wide, is between 60 and 70 percent. But among ACSC graduates, it is just about a sure thing.

Each year’s class is about 600 strong, with 400 from the Air Force. The remaining 200 come from the other U.S. armed services and from those of allied nations. Of the 600 total, fewer than 80 were United States Air Force pilots. The result of a year of ACSC was one of three outcomes: you failed, you graduated, or you graduated in the top 5 percent. Very few would start the course with realistic hopes of being in the 1 out of 20 and have “ACSC Distinguished Graduate” on their official military records. But fear of failure was real and realistic.

The total class of 600 was divided into 40 sections, each section was scientifically designed to ensure there were two Air Force pilots, two foreign exchange officers, a U.S. Army officer, and a U.S. Navy or Marine Corps officer. The balance was filled out with other non-pilot Air Force officers. Oh yes, the wizards at personnel also ensured nobody in any given section had any previous history with anyone else in that section. No former friends to make life easier.

“What are you doing here?” I asked Major Marke Gibbs.

“I was going to ask you the same thing,” he said. We were tablemates in pilot training and now we were section mates at ACSC. We weren’t the only pilots, however. Our foreign exchange student was a pilot from the United Arab Emirates and our Navy officer was a helicopter pilot. The rest of the section included an accountant, a personnel officer, a security officer, and a “Morale, Welfare, and Recreation” officer.

“Just call me ‘Mister MWR,’” Major Tom Taylor said. “Or you can call me ‘Mister T.’ But whatever you call me, your morale is my business!”

Our first block of instruction dealt with military history and the reading list topped 200 pages every night. After the first night, I realized most of the reading was needless background material. Since each lesson included a list of objectives, I skimmed the material and read only the sections that supported the objectives. I condensed the 200 pages into two or three.

“This is ridiculous,” Marke said on the third day. “The reading is tedious and we don’t have enough time to do it and all the other stuff they are expecting from us.” We had a paper to write, a speech to give, and a lesson to teach every two or three weeks. The reading list was obviously the first thing to go.

“Here,” I said while handing over three days of notes. “Why read six-hundred pages when you can read six?”

Our first exam, the history exam, was supposed to be the easiest of the year. Three in our section got perfect scores, but three others failed. Failure meant attending additional lectures and taking the same test over again. Mister MWR was one of the failures, but his spirits remained high. “You know what they call failure in the MWR business?” he asked the section, waving his graded test sheet for all to see. “We call it one more step in the learning process, that’s what we call it!”

We moved from the history section to the “Regional Affairs” section and the reading lists became even more disjointed. I found my skimming, summarizing, and writing routine was helping me learn and Marke was becoming an avid reader of my work. Every morning at 0700 he would whisk away the copy I provided and eagerly read before class started at 0800.

“Bernie Palmer!” I said as I finally made contact with an old squadron mate from Hawaii. “It’s been a whole month and I had no idea you were here. I guess they have you hidden in the opposite side of the building.”

“They can’t have us two in the same section,” he said. “That would just be too much fun. Speaking of which, I recognized your writing style and wanted to see if it was really you.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

Bernie pulled out a three-ring binder filled with what appeared to be almost a hundred pages of typed notes. He showed me the top page. It was what I had written the night before. I flipped through the binder and found the complete set. “Wow,” I said. “How did you get these?”

“One copy magically appears in each section’s mailbox every morning about thirty minutes before class starts. We make a copy for everyone. I think every student in the school has a copy by eight in the morning. And the only student who didn’t know that was the guy who wrote the notes in the first place.”

“That’s pretty funny,” I said.

“You haven’t changed, James.”

Marke admitted his part in the scheme and apologized for the subterfuge. “These notes are better than the reading. I thought I would spread the wealth without you knowing. That gives you plausible deniability.”

“Makes sense,” I said. “Let’s press on as before.”

On the one hand, we were cheating the ACSC curriculum designers. They concocted a system forcing us to read 200 disparate pages every night. Of the many pages, clearly only a third were germane. But was that the intent? On the other hand, we were doing as you would do in the real world. You find someone who can cut through the chaff and produce the wheat everyone really needs. I dismissed any thought of wrong doing.

The second set of exams saw our section do much better with six perfect scores and only one failure. It was another step in the learning process for Mister MWR.

Each exam was preceded by two weeks of reading (2,000 pages or 20 pages, depending on your source), classroom sessions taught by fellow students, and five speeches, also given by fellow students. While it was the speeches that most students feared the most, it was the classroom sessions where we really learned to get to measure our fellow students. Anyone could fumble a speech; public speaking is not something many like to do. But teaching an hour-long class was sure to reveal an officer who fell short on any subject.

“I feel I know less now than I did an hour ago,” Marke said as we headed for lunch after a class taught by Mister MWR. “Tom’s a good guy at a party and he’s a helluva shortstop, but he doesn’t know the first thing about nuclear warfare.”

“I’m not sure he knows the first thing about anything,” I said. “I’m amazed he hasn’t busted any exams in the last month.”

“Busted?” Marke said with a laugh. “He’s aced the last three in a row. I don’t know how he does it.”

A week later, Mister MWR aced the nuclear warfare exam. Half our class failed it. When one of the failing students asked for an explanation about one of the questions, Mister MWR couldn’t answer. “That’s last week’s news,” he said. “I have to clear the old brain for new knowledge.”

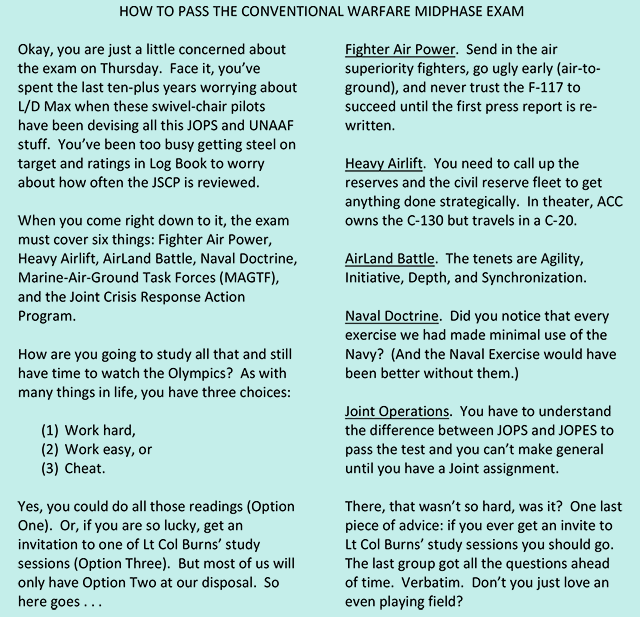

Our next block of instruction was supposed to be the toughest of the year: conventional warfare. The instructors said it had the highest bust rate of them all and we would have to double our efforts just to pass. The exam was a midterm and was expected to cover six broad topics, each of which was worthy of its own exam. Since my notes had a school-wide audience, I thought a summary page would be in order. But wouldn’t that be crossing a line from note taker to exam tutor? It was the longest block of instruction yet, so I had a few weeks to consider my notes-or-tutor role.

Our classes started every morning at 0800 sharp, but the day wasn’t done until the person teaching the last lesson said it was. It was considered bad form to end much later than 1700, but that’s where we found ourselves on a Friday, almost one week from our dreaded conventional warfare exam. We finally ended about 1720 and everyone bolted from the class, rushing to get the weekend started. I filed out of the class, last in line, only to be greeted by my Hawaii squadron mate.

“James you need to see this,” Bernie said while handing me a folded sheet of paper. “Only you didn’t get this from me.” Bernie’s voice rarely carried, even if he wanted it to. But he was almost speaking in a whisper. I unfolded the paper and recognized a summary of various nuclear warfare topics, our previous block of instruction.

“Noo-clee-ur combat,” I said. “Toe to toe with the Rooskies. So what?”

“Read it,” he said. “It is a list of twenty-five topics. Does that ring a bell?”

I scanned the twenty-five items. Then I read the first few verbatim. It was unmistakable. “This looks like the exam we just took. A bit of old news, I think.”

“I got invited to a study session a day before the exam,” he said. “The study session covered twenty-five things. I saw each item, word-for-word, on the test. The study session taught the test.”

“Who taught the class and how did you get the invite?” I asked.

“One of the instructors taught it,” he said. “It was Lieutenant Colonel Steve Burns. And I heard about these study sessions a few months ago, this was the first one I attended.”

“But how did you get the invite in the first place?” I asked.

“Only select students are invited,” he said. “Only students who look like me.”

By this time I had known Bernie for more than ten years. We had flown together in T-37s, KC-135s, and the Boeing 707. In all that time, he never mentioned his race (African-American) or mine (Japanese-American). Bernie had a good sense of humor, but this was a subject that never came up, not even in humor.

“I don’t understand,” I said.

“Sure you do,” he said.

“How long?” I asked.

“Our section had a pretty bad bust rate for our first month,” he said. “Lots of guys were having to take retests and we even had a few fail those and washed out. They said we were about to set a record. I didn’t bust any, thanks to your notes. But everyone has your notes. I guess those select officers busting exams got the invite. The only reason I showed up was someone asked me why I didn’t. So I did. And now I know.”

“And now I know too,” I said.

“You can’t let this stand,” he said. “It puts a cloud over all of us who passed the tests for real. This is wrong.”

“It is that,” I said.

Bernie smiled, telling me he was confident I would handle it. I didn’t have the slightest idea how. I usually tried to read ahead during the weekend and get a head start on the many notes to follow. I was leaning against any kind of exam tutoring in my notes, but Bernie’s news reversed that inclination. In the end, I decided on a direct, frontal assault.

“It’s a risk,” The Lovely Mrs. said. “If you jab the faculty in the ribs, the faculty is going to be unhappy.”

“The faculty is accountable to somebody,” I said.

I added the jab to the last page of my Monday notes. By noon I started to notice some kind of impact. When I returned from lunch I spotted an extra layer of faculty in our hallway, all looking my way. As I neared, they scattered like cockroaches caught in a midnight kitchen cupboard raid. My instructor didn’t reveal anything other than avoiding my glance. During the next break I caught a few “thumbs up” from some of my fellow students and a diverted stare from others.

The next day our instructor began the 0800 hour with a special announcement. “Ladies and gentlemen, I have a letter from one of our faculty that will be read to every student this morning, by order of the commandant. So, without further ado.”

The commandant was a three-star general who was only seen escorting special guests to our lecture hall and never heard from during our six months so far at ACSC. Our instructor read from the letter.

“There is a false rumor going around the ACSC campus about study sessions that (a) teach the exams, and (b) are only open to certain invited students. Both items are false. I have been holding these study sessions in hopes of providing a broad-brush approach to each block of instruction. These have been by invitation because of the limited space at my base house. The rumors do bring up the need to widen the audience, so the next study session will be held in the ACSC main conference room on Wednesday at 1800. All ACSC students are invited. Signed, Lieutenant Colonel Steve Burns.”

“So,” our instructor said while putting the letter away, “I hope that clears that up. Now we can begin our scheduled lesson.” All but two of my section mates gave me nervous smiles. Mister MWR gave me an angry scowl. Marke Gibbs gave me a broad smile and two thumbs up.

I didn’t attend the newly publicized study session but later that night I got a call from Bernie. “You should have been there,” he said. “It was pretty funny. Colonel Burns welcomed the large audience and then gave the most worthless summary of the last six months you can imagine. You could tell the regulars were getting upset. When Burns finally ended it, nobody was happy. It was a waste of a couple of hours. It’s going to be a blood bath tomorrow.”

And it was. Our class set a new ACSC record for failures on an exam. Bernie scored in the high nineties as did most of my section. Our only exception was Mister MWR, who failed miserably.

I pushed thoughts of the special study sessions aside and busied myself with finishing the program in the top 5 percent of the class. Class standings were dependent on our test scores, written reports, speeches, and lab work. I had aced every test and done pretty well on just about everything else. But, as I had feared, not well enough. Or so I thought. I did the math and figured that I was the guy just below the bottom guy on the top 5 percent list. That guy.

On our final day at ACSC we all sat in the auditorium to hear the results of the year. The commandant came to the podium and said it was his honor to read the list of the top 5 percent. “Each of you should stand as I call your name and remain standing until all 30 names have been called. Please hold your applause until then.”

He then started off on the alphabetical list. “Major Sean Adams,” he began. One by one each major rose. In one case it was a civilian “Mister” and in another it was a Navy lieutenant commander. It happened halfway through the list. “Major James Albright,” he called. The audience broke its vow of silence and applauded and my section mates pushed me out of my seat. “That’s you James!,” they said. “Stand up!”

I rose and remained standing until, “Major Calvin Zeno.” More applause.

As we filed out of the auditorium our instructor shook our hands and wished us well. As he shook mine he said, “hang around a bit, James. I have something for you.”

After the last of our section had been wished well I followed my former instructor to his office. He was a major, just like me. I would probably never see him again.

"General Boyson wants you to know you were going to end up on top of the distinguished graduate list no matter how the scores worked out," he said, pausing to let that sink in. "The entire faculty knew about your notes and that brought home the fact the curriculum had gotten out of control. Before the cheating scandal there was unanimous faculty support for you."

"And after?" I asked.

"Well, that's interesting," he said. "I think there was a faction that wanted to hang you for insubordination. But I think the fact you are a distinguished graduate tells you who won that argument. To be honest with you, James, I am surprised how it turned out. You risked your graduation just to make a point. I'm not sure I would have done that. But it paid off for you. Congratulations."

I thanked him for his support and walked off the ACSC campus, never to return. I was nominated to attend the next level of officer school but retired before that came up in the assignment rotation. I don’t know what happened to Lieutenant Colonel Burns or Major MWR. But Bernie and I went on to be lieutenant colonels and both became squadron commanders. Marke Gibbs bested us both. He became a two-star general.

Thinking back to my days as an Air Force ROTC cadet, I remember my first year instructor was an Air Force captain, intelligence officer. My first memory of him was whenever a cadet would say, "you know . . ." he would say, "No, I don't know." My second memory of him was the way he taught the class as if he had personally written the lesson plan. He never used notes and everything seemed to come from his heart. When we talked about integrity we of course discussed right versus wrong, good versus evil. There was no argument there. But he also talked about "stake." "What is your stake in the game?" But more importantly, he said, "What are you willing to put on the line for the sake of your integrity?" There is risk there. When the time comes, what are you willing to risk?