"The Rules" are twenty-six ideas I've collected over the years that seemed relevant enough to life in general that I've written each down with a short story to reinforce each in particular. This is Rule Number Twenty-five.

— James Albright

Updated:

2014-02-01

Being calm under pressure is a valuable skill for a pilot. I say skill because I do believe it can be learned, though some people seem to have the ability innately. I've been accused of that and I suppose it might be true. Almost eight years into my flying career it almost came to an end with cancer. I wrote this a year or so after that. Since then I've had two more visits from cancer. I am starting to think I am invincible. Pilots shouldn't think like that.

So this is a story more about Rule Number Twenty-Five than it is about remaining calm: don't worry about things you cannot control.

Don't worry about things you cannot control

1988

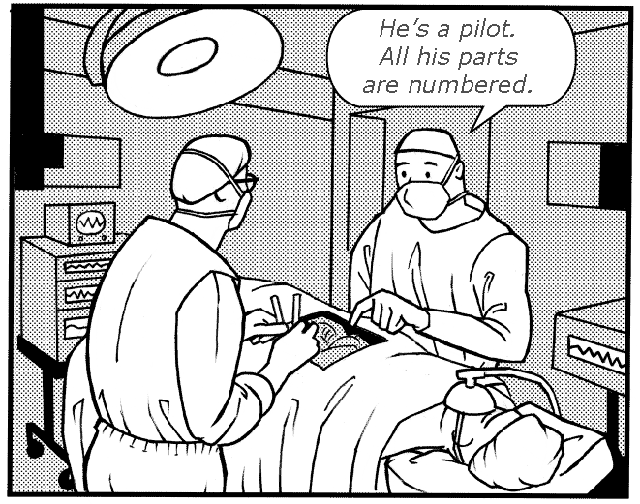

“He’s sleeping, can you believe that?”

I wasn’t sleeping. At least I don’t think I was. They left me alone on the hospital gurney in the hallway for what had to be an hour, so what better to do? Besides, I was tired. Two weeks ago I was in Japan racing through the Ginza district trying to get back to the airplane in time to spare the other backup crew, two days ago I was in the base hospital being told I had cancer, and two hours ago I was in the cancer ward being told they were going to cut my balls off. I deserved a little shuteye. Besides, a good possum can collect excellent intel.

“What’s the delay?”

“We can’t start until the OSI agent gets here.”

“What?”

“The patient has got some kind of super-duper security clearance.”

“I thought he was a pilot.”

“He is.”

At last there was movement. They wheeled me into a cold room that at first seemed eerily dark but eventually I was beneath a sea of light. I opened my eyes to a beehive of activity. There were at least ten people in there, all wearing white gowns and masks. Doctor Frost, the no-nonsense, no-humor man from yesterday, addressed the crowd. “Recorder on?”

“Yes, doctor.”

“Okay then, our patient is a code word officer and as such we have a security agent from the Pentagon here. Major Beterline, you have a briefing for us?”

I looked over and saw one of those typical OSI spooks. He was in a standard blue uniform with a lightweight jacket that did a poor job of hiding the weapon in his shoulder holster.

“The captain doesn’t have a history of speaking in his sleep,” the mysterious figure began, “but as you all know, you never know how somebody reacts under anesthesia. So once he is put under, the room must remain secure, nobody enters or leaves without my permission. If the captain does say anything while sedated, I will evaluate his statement and if security is breached...”

“You’re going to shoot everyone in the room,” I said.

There was a gasp. I thought it was funny. I guess I was the only one.

“No, captain.” He had obviously heard this one before. “We will have to place everyone here under oath, sign a mountain of paperwork, and then I can get on my flight and go home.”

“Okay then,” said the doctor. “Well I guess you’re in good spirits. Any questions before we begin? Allrightee. We’re going to put you out now. Try to count from ten to zero, backwards.”

They lowered a transparent mask over my head and I began and finished in one word: “Ten. . .”

Recorder?”

“It’s on, doctor.”

“Okay. Patient is a thirty-two year old active duty Air Force pilot with a recently discovered left testicular mass. He was referred from his base with a concern for a testicular tumor. He is married, has one child, is lean, and appears to be in good health. Temperature ninety-eight point four, pulse fifty, pressure one-ten over seventy. We performed a left radical orchiectomy and lymphangiogram with no complications. Embryonal carcinoma is indicated.”

“That’s the bad one,” I said.

“Whoa,” the doctor jerked his head toward me, “you’re up! That’s great. The surgery went very well, captain. The bright lights will dim in a few minutes and any grogginess is normal.”

“You said embryonal. . .”

“We’ll talk more about that in a few hours, you need to rest.”

Somehow I slept. I woke up in a fifteen by fifteen room in the only bed seated opposite an open window. The walls were pale yellow, about ten years overdue a coat of paint. Other than the hospital bed, the furniture was standard Air Force, the result of a good deal contract some wholesaler in North Carolina secured with a friend in Congress. The door was open and I could see medical gowned people scurrying about. My head was propped up by the bed’s incline and other than feeling tired, I was comfortable.

Just as boredom started to set in a young, female orderly came in. She placed a clipboard at the foot of the bed and with one hand clamped the ears of her stethoscope into position. The cold end of the instrument went to my forearm as she held my wrist with the equally cold end of her fingers. I watched intently as she concentrated on her count. She gripped my wrist tightly.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“You don’t have a pulse.”

I looked into her blue eyes. “I do.”

“You don’t.”

She dropped my wrist and hit a button on the wall above my head. The flash of a red light illuminated the hallway and I heard an army of feet rushing towards us. The first head in the doorway was another orderly followed by a nurse or two and then by a doctor I’ve never seen before. “What’s going on?”

“Doctor,” she said almost teary eyed, “he has no pulse.”

I smiled at the doctor and shrugged my shoulders. “I’m no cardiologist, but I am pretty sure I got a pulse.”

That commotion ended, the medical brigade left and my doctor, an Air Force major, entered. “Ed,” he said while shaking my pulse-less hand, “I’m Doctor Frost, the operating surgeon.”

“You said embryonal carcinoma was indicated.”

“Yes it is,” he said without a change to a single facial muscle, “I’m sorry.”

“Isn’t that kind of rare?”

“Oh no. It isn’t the most common type, but we do see our share of these. I guess you know that if you are going to get testicular cancer, this is the one to avoid.” I let his words sink in and tried to remember the details from the glossy pamphlet he had given me when we first met. “So You’ve Been Diagnosed with Testicular Cancer” certainly wasn’t the best reading I’ve done lately, but given the circumstances I read it twice.

“Are you sure?”

“Well we can never be sure,” he said, “not until we get the path results. But I’ve done a lot of these and I can recognize embryonal when I see it.”

Embryonal carcinoma, while not common, was the deadliest of the three types of testicular cancer and cures were hit and miss. I was placing my hopes on seminal carcinoma, seminoma it was often called. While it was once also death warrant, in recent years the survival rate had gone from ten, to thirty, and now to nearly eighty percent. But that was only a distant hope.

“So what does that mean for my future?”

“Well that’s hard to say,” he said with just a mild head shake, “I know you are probably looking for a percentage.”

“That would be nice.” A percentage is exactly what I wanted.

“Well we don’t do percentages,” he answered, “they only do that on TV. We can say, however, that the likelihood of surviving the first year after a diagnosis of embryonal carcinoma is less than one in ten.”

“So fractions are okay,” I said, “percentages are not.”

He ignored my stab at humor and detailed the next two months of my life. It would be in the hospital in that very bed. The first two weeks were for me to learn to walk again after they cut through my left hip muscles. That would be followed by massive doses of radiation to my chest and smaller doses of chemicals for the rest of me. This type of cancer travels north to the liver, the lungs, and eventually to the brain. The treatment would prolong my life, to be sure, and perhaps offer me a shot at one of those coveted one in ten odds.

“You need to update your will,” he said, “and let your loved ones know exactly how terminal this is.”

“Why?”

“It is only fair,” he said as if repeating a rehearsed script, “your death will be a tremendous shock and they need to be prepared. If you feel uncomfortable about this, I can call your wife and your parents.”

“No. Let’s wait for the pathology results.”

“I told you . . .”

“Don’t call anybody. I want to wait.”

When I began this ordeal the base hospital referred me to a civilian doctor who confirmed I had cancer. He set me up for the surgery at a hospital in Omaha and that all sounded fine. The Air Force turned that down because the base’s budget was stretched thin and said I would have to go to a military hospital, the cancer ward in San Antonio. Now these military quacks are telling me I’m going to die. That can’t be right.

Learning to walk again wasn’t nearly the ordeal they said it would be and I spent most of each day wandering the hospital between CAT scans, X-rays, blood work, and the cafeteria. Once the radiation started, however, I was in bed most of the day refusing meals and asking for beer. After two weeks, I was granted a single beer each day in exchange for the promise to eat at least one meal a day. It was a good exchange. The beer made the peanut butter sandwich palatable.

Boredom. That was what would eventually kill me. The lovely Mrs. got my laptop computer onto a military flight and with just a few phone calls I found it sitting outside my hospital room on the floor. Late that night I visited every empty room on the floor and ended up with a very nice table that could suspend my laptop right over my bed, several extension cords, and ten or fifteen notebooks with the right kind of graph paper. I identified several printers that would do the trick, but decided that kind of theft would have to wait.

I had a list of programming requests in a generic text file on the desk top. My real plan was to keep the list in its pristine, never looked at, condition. But that was then and this was now. I started on item one.

Every day began and ended with an orderly taking my vitals, my blood, and a little bit of my patience. In the morning we were treated with pressure one-ten over seventy, pulse at fifty, respiration between twelve and fifteen. In the evening all those numbers were higher. Being in the hospital wasn’t so bad. It was having to deal with the doctors, nurses, and orderlies.

At first the doctor would visit every morning. At each meeting I would ask about the pathology results and he would answer with the same words each time. “Not yet, but don’t worry. These things take time.” After a week the visits became less frequent and by the third week he didn’t come in at all.

My list of programming projects was shrinking and a few days passed to where my only tether to my real world situation was the twice-daily vitals ritual.

Month two began with daily visits from First Lieutenant Liz, the hospital psychologist. I hated her from the start, that Lieutenant Liz. Half Lieutenant, I thought. She was half the size of a normal lieutenant, had half a smile always pasted on her face to go with half eyebrows that may or may not have been painted on. On day two I suspected she had half a brain.

“You are angry,” she said, half-heartedly.

“I’m not angry.”

“It is only normal to be angry when you find out you only have a few months to live. Normal.”

“I’m not angry.”

“How can you not be angry?”

“I have no control over the situation, nobody is to blame, there is nothing to be angry about.”

“You may not know that you are angry.”

“How can one be angry and not know it?”

“You sound angry.”

“I’m not angry,” I repeated, “I’m not denying that I am angry, I’m not bargaining with you, I’m certainly not depressed, and I’m not even hopeless about it. Perhaps I can jump a few steps and tell you’ve I accepted it and we can bypass all these five stages of grief, or whatever your textbooks call it.”

“There is no reason to be angry with me.”

“I thought you said it was normal.”

“Well,” she said with half her enthusiasm, “I can see we’ve covered a lot of ground today. I’ll see you again on Monday.” And with that, she was gone.

The bloodletting was becoming routine.

“Just a little stick,” said the orderly du jour while aiming her dagger at the bend of my left arm.

“Felt more like a tree,” I said. “You done this before?”

“You’re my first.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, when words about the size of your veins got around, the hospital started sending all the trainees up here.”

Terrific.

“Why can’t I come down for a visit?” The lovely Mrs. was upset.

“Because we can’t afford it. I’ll be home in a few weeks. The radiation treatments are almost done and as soon as my white blood cell count recovers, they’ll release me.”

“James, I’m worried.”

“I’m not and you shouldn’t be either.”

“It’s cancer, James. The odds...” Her voice trailed off.

“The odds are good,” I lied. “I’m not worried. I’ll be home before you know it.”

“Is there anything I can do,” Half Lieutenant Liz asked at the start of session five, “anything at all?”

“Get my pathology results.”

“That’s up to the cancer ward.”

“Then stop coming here.”

“Oh you don’t mean that,” she protested, “we are doing good work at these sessions.”

“No, you are depressing me. I feel fine every day until I see you. Just the thought of you fills me with dread. Don’t ever come here again.”

“But it’s my job.”

“You are an Air Force lieutenant and I am an Air Force captain. I am ordering you to never be within my line of sight ever again. Is that clear?”

“Yes, sir.”

That actually felt half good.

The blood work was reduced to every other day and the vitals to once a day. Without the hospital shrink bothering me, I got to the last item on the programming list, wondering what I would do next. As I started on Item Last, my missing in action doctor appeared.

“The scar is healing nicely,” Doctor Frost said while giving my groin one of those clinical thumps, “your white blood cells are still low but no longer dangerously so, I think we can release you tomorrow.”

“What about the pathology results?”

“Oh those came in a month ago,” he said with the first bit of expression I had ever seen in his pock-marked face, “didn’t we tell you?”

“No.”

“Oh, that is unfortunate.”

“So you gonna still keep it a secret or do I have to beat it out of you?”

“Oh, sorry. It’s seminal carcinoma.”

“So about fifty percent survival odds?”

“We don’t do percentages.”

“Five in ten probability of surviving beyond a year?”

“Five years, actually. In fact, we are returning you to flying status.”

This was great news; it appeared the next item on the list was: "aviation, resume."