In his excellent book, “On Combat: The Psychology and Physiology of Deadly Conflict in War and Peace,” Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman says that “Whatever is drilled in during training comes out the other end in combat - no more, no less.” He quotes a wise Gunny Sergeant:

“In combat you do not rise to the occasion, you sink to the level of your training."

Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus put it another way around 100 AD:

“Whatever you would make habitual, practice it; and if you would not make a thing habitual, do not practice it. but habituate yourself to something else.”

If you've been a professional pilot for more than a few years, you can probably see where I am going with this.

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-10-15

Grossman gives us a real-world example of how practicing the wrong thing can kill you:

“One example of this can be observed in the way police officers conducted range training with revolvers for almost a century. Because they wanted to avoid having to pick up all the spent brass afterwards, the officers would fire six shots, stop, dump their empty brass from their revolvers into their hands, place the brass in their pockets, reload, and then continue shooting. Everyone assumed that officers would never do that in a real gunfight. Can you imagine this in a real situation? ‘Kings X! Time out! Stop shooting so I can save my brass.’ Well, it happened. After the smoke had settled in many real gunfights, officers were shocked to discover empty brass in their pockets with no memory of how it got there. On several occasions, dead cops were found with brass in their hands, dying in the middle of an administrative procedure that had been drilled into them.”

So, how does this relate to us in the business of flying airplanes? Consider a few of the selected arguments I’ve had in flight simulators.

1 — “The critical engine always fails” – The V1 manhood test

2 — “You would never do this, but do it now” – Circling when better options exist

3 — “Watch this” – Competing for the lowest altitude no-engines landing

4 — “New jet, new day” – Skipping an emergency procedure’s aftermath before flying

1

“The critical engine always fails”

The V1 manhood test

I was going through an initial course paired with another captain who was considerably younger than me but who had time in type as a copilot where the airplane was new to me. I was in the left seat for our first engine failure at V1. As I’ve always done this, I allowed the nose to track before correcting with rudder and pressed on. The instructor said he was sure I could do better, but I wasn’t sure what he meant. When the other captain got her chance, her rudder correction was so fast I wasn’t able to sense any yaw at all. “Outstanding!” the instructor said. This went on, sim after sim. The instructor asked me why my reaction timing was so slow. I told him that was the wrong question. The right question was why was her timing so quick? She said it was because of her excellent eyesight and lightning fast nerves. I asked the instructor why he always failed the left engine. He said because it was the critical engine and that’s the engine we were to lose on the check ride. I thought about that for a while and for our next training ride I had a proposal. I told the instructor this training would kill someone someday. He said I was wrong. So, I convinced him to fail the right engine that day without warning her. He agreed to do that just to prove me wrong. You can see where this is going. Our simulated deaths were mercifully quick.

Sink to your training: if every engine failure in the simulator is the critical engine, how certain can you be that your response to the non-critical engine will be correct?

More about this: V1

2

“You would never do this, but do it now”

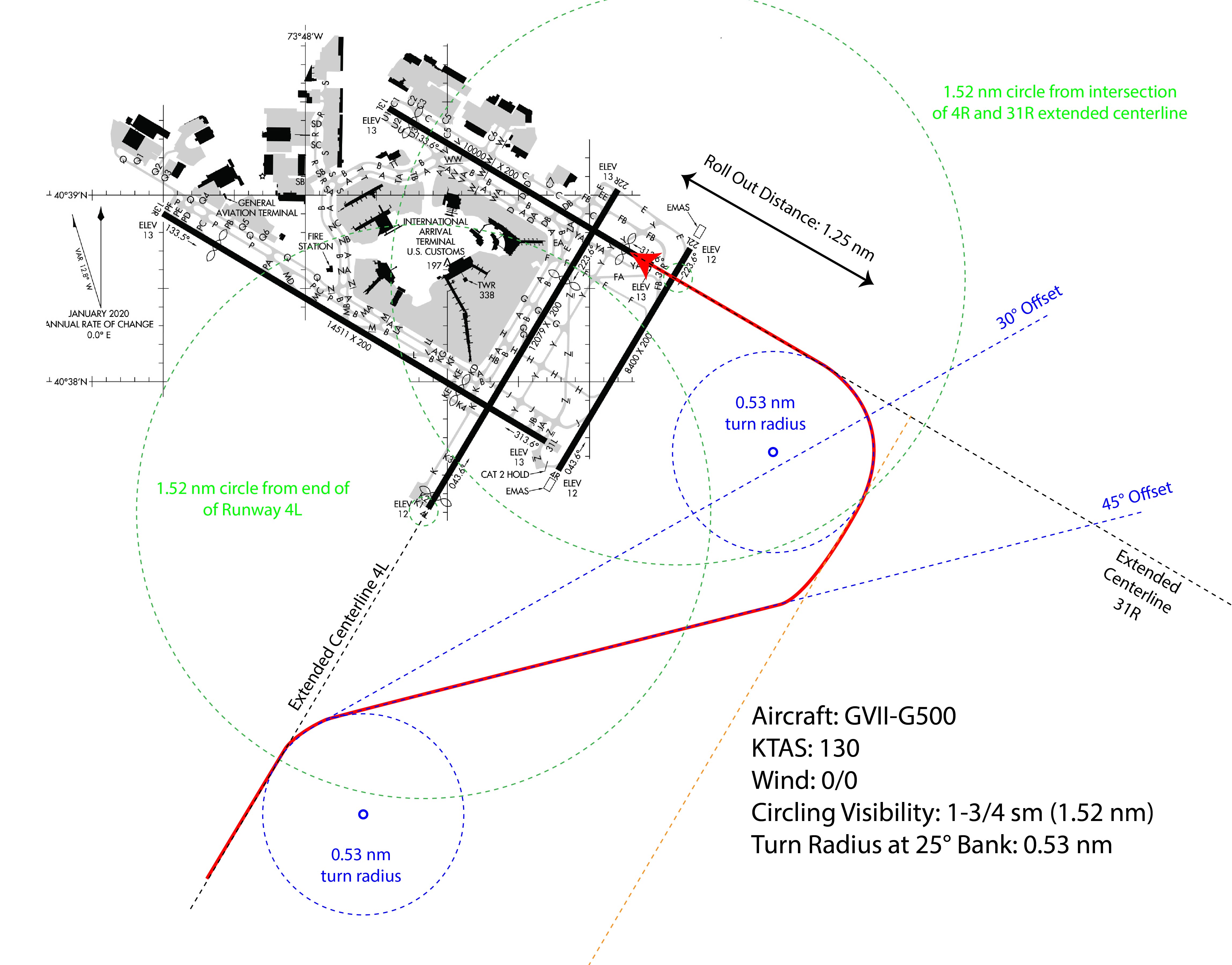

Circling when better options exist

“Why can’t you do this?” is how the argument usually begins.

“Because you told me to only fly stable approaches and that is impossible off this circling approach.”

The instructor would say I’m wrong and then I would bring out my charts and diagrams.

“Well, do it anyway. You want to pass your check ride or not?”

Why are we surprised when another jet crashes during a circling approach they should have never attempted?

Sink to your training: Just about every circling approach in the books cannot be done at minimums and end up with the aircraft on course, on glide path, on speed, at least 500 feet above the touchdown zone. So why are we practicing them that way? When presented with a choice of circling at minimums or diverting, the wise decision might not have been the one your trained for.

More about this: Circling - Good Riddance

3

“Watch this”

Competing for the lowest altitude no-engines landing

I wanted to know how much altitude I needed to successfully turn around and land safely after losing both engines in a Gulfstream G450. After a few tries, we concluded that if you lost an engine at 1,500’, you could turn downwind, base, and final and land without too much trouble. You could also do a 90°/270° to land on the takeoff runway. Below that altitude, you are probably better off picking a spot to land straight ahead. Good to know. When the next pilots from our flight department went to training, they came back with stories of losing both engines at 500’, turning at 80° of bank at 2.5 G’s, rolling out on final to the takeoff runway, and landing. It took them several tries. If you ever lose all thrust at 500’, you only get one try.

Sink to your training: When we practice the impossible over and over again to make it possible, we tell ourselves it is not only possible, but it is easily so. Remember your job is to allow the people to walk away from the aircraft. Even if that isn't connected to a jetway or with the airstairs on the red carpet.

4

“New jet, new day”

Skipping an emergency procedure’s aftermath before flying

Yes, in the training environment we are trying to cram as much training into as little time as possible. But perhaps something more can be done that how it has always been done. Picture this, you lose a tire during takeoff, it shells out an engine which is now on fire, the aircraft is vibrating wildly, and it is all you can do to get the thing back on the runway. After you do that, the instructor says, “Taxi her to the end of the runway, program another departure at maximum weight, I’ll repair all the damage, reset all your switches up there, and let me know when you are ready. New jet, new day.”

Is this a bad thing? Consider one example of many the case of Lerajet 55 C-GCIL, which on March 17, 2009, did the classic simulator exercise where the crew had to succesfully abort a takeoff, taxi back, and takeoff again. Only they weren't in a simulator. During their initial takeoff the tower transmitted that there was smoke coming from the airplane. They were only doing 80 knots, so they aborted. In the next 5 minutes and 43 seconds, they taxied back, apparently inspected their aircrat to assure themselves there was nothing to worry about, and started another takeoff. This time they heard a loud bang, the aircraft yawed to the right, and they aborted again. Then came the second bang. They were able to stop and evacuate the aircraft with no injuries. The aircraft was damaged, however. The NTSB cited the crew's "failure to follow the manufacturer's aircraft flight manual emergency procedures following a rejected takeoff that required a high energy stop inspeciton." I suppose all that is true. But maybe the crew was just doing as they had been trained. Repeatedly.

Sink to your training: Getting knee deep into the emergency procedures section of your manuals should never be resolved in a few minutes. Just because you get to the “Checklist Complete” line of your emergency procedure and landing successfully might mean the emergency is over, but it doesn't mean the learning is complete.

References

(Source material)

Aviation Investigation Final Report, Accident Number: WPR09LA151, Casper Wyoming, March 17, 2009, Gates Learjet 55, C-GCIL.