Years ago in a Gulfstream III, I came back from a flight where one of the partial glass displays did something weird, it completely blanked and then appeared two letters, a "D" and a "U" as big as the screen. I called Gulfstream and they refused to believe it. "That can't happen." This was 1992 and there may have been digital cameras out there, but I certainly didn't have one. But as soon as I could afford one, I got one. And that has made all the difference.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-04-15

A few years before my GIII incident I had a few in the Boeing 707 that could have cost us an airplane with over thirty people on board. So let's use that as a starting point and press on to how a camera can help you troubleshoot an elusive airplane problem.

1 — Boeing 707 "false" fire light

2 — Gulfstream G450 landing gear timing valve

3 — Gulfstream G500 autothrottle engage

1

Boeing 707 "false" fire light

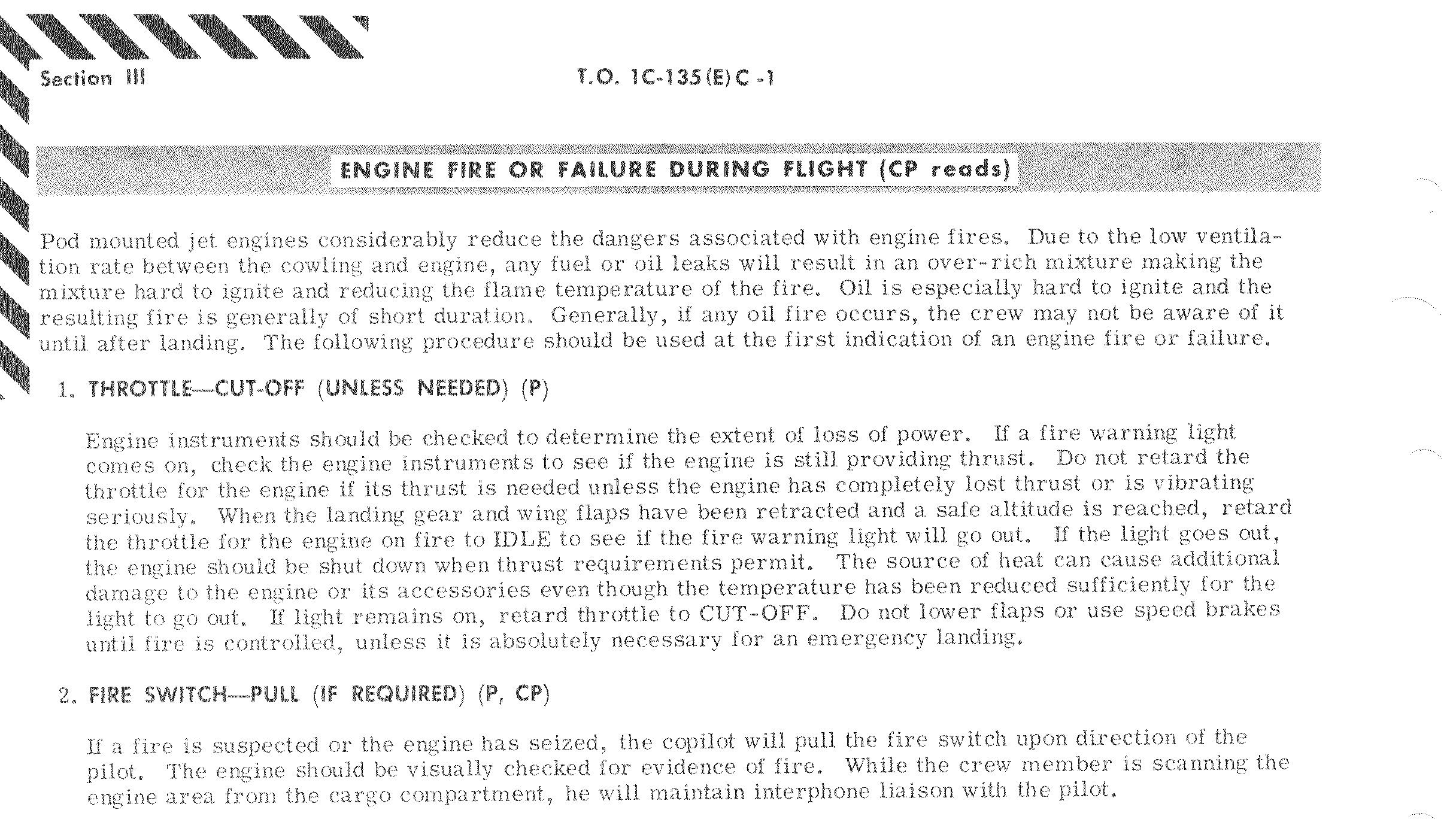

In 1985 I was a fairly new aircraft commander in an Air Force Boeing 707 (EC-135J) based out of Hickam Air Force Base in Hawaii. One of our standard missions was to takeoff at maximum grossweight with a full load of passengers, heading for the Philippines. On one of these trips, the number three engine fire light illuminated. I shut the engine down, turned around, and returned home.

For this episode, everyone was happy we made it back in one piece but my hero status lasted less than a day, because maintenance said there was nothing wrong with the engine. A more senior crew hopped in the jet, fired up all four, and flew a training mission of four hours. In fact, the airplane flew a regular schedule of local training missions for the next month with nary a hiccup from that engine. I went from hero to zero in the blink of an eye.

About two months after the original episode I was again flying the airplane headed for the Philippines with a different crew but the same set of passengers when the number three engine fire light lit up again. "Shut it down," I said. "Really?" asked the copilot. "Yes." We came home again, this time with some very upset passengers. After maintenance pronounced the engine healthy with the infamous, three-letter return to service write up, CND or "Could Not Duplicate," the squadron commander hit the roof and therein began the great "By the book" debate of 1985.

Our engines had simple fire loops with no fault detection system to tell us if the system was working properly. More importantly, we didn't have any fire extinguishers and the book left us no choice but to shut the engine down. I think the squadron divided itself into two, half of us saying the book meant what the book said, the other half saying we were issued superior judgment for a reason. As the airplane logged a dozen more trouble-free local training missions, the superior judgment crowd was emboldened. There was nothing wrong with that airplane.

As the weeks went by, I chided myself for not taking better notes before shutting the engine down. I should have recorded the readings from all four engines. But that would have taken time and did I want to take that time if the engine was on fire?

Two months later, I was in California attending the Air Force Accident Mishap Investigation Course while another pilot took my crew on the now infamous maximum weight takeoff trip across the pond. The fire light made its appearance and the guest aircraft commander announced it was a known problem and he was going to press on. Though he clearly had superior judgment, my crew set up browbeating him to reversing his decision. After an hour he agreed to come home. They landed after two hours of flight with the engine engulfed in flames. I think had they been airborne for just a few minutes more, they could have lost the wing, but some will say the worst thing that could have happened is the engine would have burned itself off the pylon.

As it turned out, there was a loose bleed air duct in the engine that would only work its way loose enough to allow hot air to escape when the engine was at full thrust for prolonged periods, such as during a maximum weight takeoff. It would often take 30 minutes to climb to altitude and the fire light usually came on after 20 to 25 minutes. The local training flights were never at such a weight and the climb to altitude rarely took more than 15 minutes. Years later I thought a video camera from the jumpseat would have been enough to keep troubleshooting rather than decide the pilot was imagining things.

Fast forward thirty years . . .

2

Gulfstream G450 landing gear timing valve

One of the advantages of flying one particular aircraft exclusively is you get to know it and you more quickly detect when something is amiss. In 2014 I got the feeling the gear extension on our G450 was taking longer than I was used to. When in the right seat, I am in the habit of moving the gear handle down and keeping my hand on the handle until it has completed extension and I have three green lights. In the G450 I also look for the red light in the handle to extinguish. The green light that indicated the right gear was down and locked was taking almost two seconds more than the left. So I started verifying that with the synoptic.

Gulfstream said it was all within tolerance and there was nothing to worry about. I said it may very well be in tolerance, but the fact it changed its behavior could mean something was wrong and could get "wronger." I was a little confused on why they pushed back until our mechanic reminded me that the landing gear was still under warranty and any repairs would be "on their dime."

Our airplane has several cameras providing exterior views, one of which is forward of the landing gear, facing aft. While we can view these up front, we don't have a way of recording the video. So I rigged a system in the cabin:

I simply removed the cushions from the forward divan, and secured a camcorder on a tripod using the divan's lap belts. Then we gave it a try. . .

A view from the aft-looking camera on a G450, the left gear down and locked, the right gear still in transit

Click photo for the video

Based on the video the experts came to the "that ain't right" conclusion and asked us to bring the airplane in.

G450 main landing gear extension test on jacks, the left gear down and lock, the right still in transit

Click photo for the video

They put the airplane on jacks and verified the problem and isolated the issue to a worn bushing on a timing valve, which is a mechanical piece of wizardry that delays gear extension until the door is clear. They replaced the bushing and everything works as it used to.

The overly dramatic pilot in me thinks that had we not caught this when we did, the bushing might have failed during flight and prevented the gear from extending at all. My mechanic tells me I am being overly dramatic. Of course he is right. Or is he?

3

Gulfstream G500 autothrottle engage

Gulfstream GVII-G500 on approach to Henderson Executive (KHND), 19 October 2019, (Matt Birch, http://visualapproachimages.com)

The manufacturer's experts will often ask, "are you sure?" or "did you follow our procedures?" in what seems like an attempt to put the blame on us and take the issue out of their in-box. We as pilots are quick to blame the airplane because we are, we think, blameless. But as they so often say in the news business, "roll the tape!" Here is an example where the troubleshooting ended up pointing the finger right at me.

I've been flying with autothrottles since 1986 and up until this year, my technique during takeoff was to push the throttles forward slowly before engaging them. In the Gulfstream GIV, GV, and G450 (all with Rolls-Royce engines), the AFM required a minimum EPR on the engines prior to engaging. All that worked well.

I went to initial GVII school last year and learned the new Pratt & Whitney engines don't have EPR gages and there wasn't a minimum N1 target to shoot for. You simply push the throttles forward and make sure you engage the autothrottles with each engine's N1 within 10%. Easy. It always worked in the simulator. It also worked during our two acceptance flights and for every flight for the next month. But then, all of a sudden, it didn't. Gulfstream very helpfully gave us a new throttle quadrant, but that didn't help. For some reason, the autothrottles didn't always engage during takeoff. Whenever that happened, they would engage once we were airborne.

I took videos of several takeoffs with a focus on the throttles and engine instruments. Gulfstream said, "A ha! You had more than a 10% N1 split."

G500 autothrottle engagement attempt during takeoff, using older technique

Click photo for the video

We replayed the tape over and over and found the left engine lagged the right, but when we hit the engage switch the left engine was only slightly behind, 40.2% N1 Left, 45.3% Right. "That's only 5.1 percent! Much less than ten!" Wrongo. It comes to [ (45.3 - 40.2) / 40.2 ] x 100 = 13%.

What we had been doing is slowly bringing the throttles to midrange, waiting for them to come up, and then hitting the engage switch. As it turns out, we were attempting to engage at the moment the lag was at its greatest. The aircraft accelerates so quickly that if we waited much longer, we would be beyond 60 knots, where the autothrottles go into "hold" mode. So we had to pull out the books and figure out what has to happen for the autothrottles to engage during takeoff: the throttle levers have to be forward at least 19-degrees, the KCAS must be below 60 knots, and the engine N1 split cannot exceed 10%. So we started pushing the throttles forward about halfway and then hit the engage switches without waiting for the engines to spool up. It has worked perfectly ever since . . .

G500 autothrottle engagement attempt during takeoff, using newer technique

Click photo for the video

If you watch the video, look at the top dials in the stack of engine instruments, that's the N1 indication. As soon as the pilot moves the throttles you will see a small circle parked outside the dial race clockwise to show the pilot what thrust setting he has requested. The pilot selects the autothrottles and they engage immediately, because the throttle lever angles were high enough, the airspeed was below 60 knots, and the engines were still near idle but with a split of less than 10%. So this was a case where we pilots were operating our GVII-500 the way we learned to operate our G450. The video helped us to learn our mistake. I published this a few months ago here:

GVII User's Group / Autothrottle Differences

Since then I've heard from a number of other new G500 pilots who ran into the same problem but knew immediately what the problem was because of the lesson we learned from the video.

4

How to troubleshoot with video

Step One: Establish "Normal"

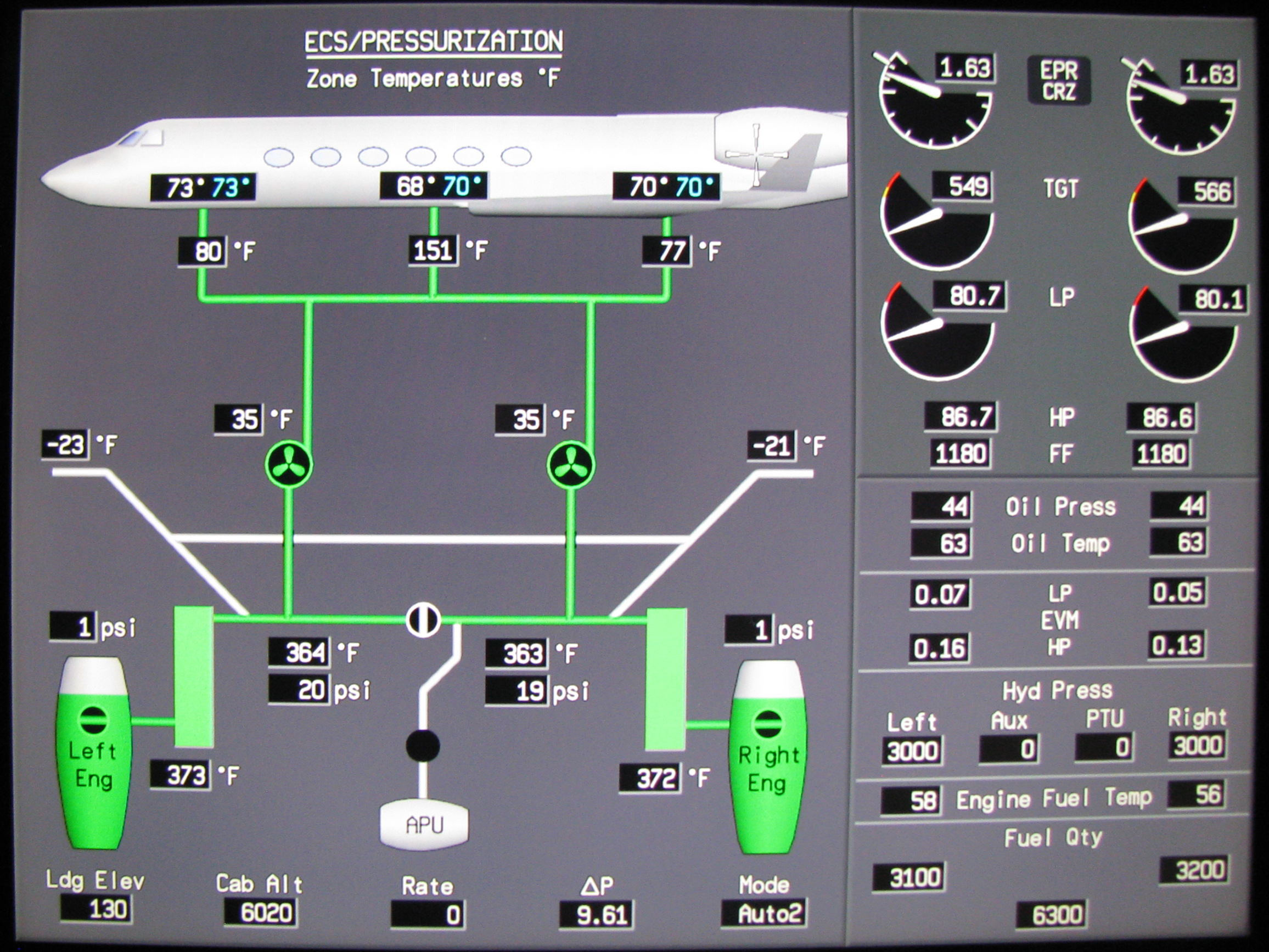

Many modern aircraft have system synoptic pages that speak volumes about what is happening "behind the curtain" but how do you know if what you are seeing is normal?

It would be a good idea to take a cell phone photo of each synoptic page and leave that on your phone for the day you have to ask yourself, "what does normal look like?" It would be a good idea to do this while in cruise flight, since that is where most of your troubleshooting is going to be. I did that ten years ago in our G450 . . .

I like to have a video of certain synoptics from takeoff to landing, just to see the system in action. The hydraulic system, for example, can have changing pressures and quantities during gear and flap movement.

Step Two: Lights, Action, Camera!

If things appear to be amiss, it may be a good idea to catch the culprit in the act. Years ago one of our regular passengers said he was feeling what he called bumps to the pressurization during cruise flight. I had not noticed but a view of the aircraft's ECS synoptic page showed the pressure jumping up and down a bit. I wrote it all up and set our mechanic loose on the airplane. He could not find anything wrong.

On our next flight with the same passenger we got the same complaint, so I took a video of the synoptic. . .

Step Three: Analyze

We sent that off to Gulfstream who said it was due to changes in the engine settings. (If you look at the video, the bleed pressure does appear to bounce around too.) We retook the video with the autothrottles disconnected and a clear view of the engine instruments. With the engines and bleed pressure steady, the pressure bumps persisted. We brought the airplane to the service center and after a day of troubleshooting they discovered we had a bad motor on our Thrust Recovery Outflow Valve, a modern version of a simple pressurization outflow valve. They replaced it and the problem went away.

The video helped them narrow their focus on the pressurization system and away from the engines and the pneumatic system. That probably saved us a few days of labor on the hunt for a solution.

Notes About Camera Placement

Synoptic video grabber

We have it easier in the GVII, since we don't have a yoke in the way and we can mount a camera to a deployable table that is allowed to be deployed during takeoff and landing. I bought a surface clamp that I put around a cloth to cinch onto the table. In the past, when the opportunity arose, I put a person in the jump seat to steady a camcorder on a tripod.

A GoPro set to record a synoptic page from takeoff to landing

Click photo for a sample synoptic video taken with this method

Cockpit video grabber

The key to a good camera installation is that it cannot get in anyone's way, getting into or getting out of the airplane. We can mount a camera using a rubber handle bar grip around a handle built into the inboard hand hold of the copilot's seat. This was the position used for the video shown above showing autothrottle engagement.

Pilot's view video grabber

The GoPro has a wide angle lens that can capture a lot from left to right. The later models record in "4K" and as fast as 60 frames per second. While you might find what you are looking for by simply playing back the video on your computer, some video editing software can help you zero in on what ails you.

Camera mounted on pilot's side window with "just in case" straps

Click photo for a sample video taken with this setup

Your video as a tool

As aircraft become more and more reliant on computers, things can get complicated. Don't take your mechanic's "that can't happen" as an attack on your observational skills. It could very well be that he was taught that what happened, really can't happen. A video or photo will help you both track down what did happen, and perhaps convince the people who built the airplane that they too have a few things to learn about that cosmic airplane you are flying.

5

Notes about cameras

My camera choices: FujiFilm XT-3, Sony RX100V, Nikon D750, GoPro 7 Black, Sony HXR-NX80 (photo taken with an iPhone 8)

You often hear cameras differentiated by the sensor size, but this can be misleading. More on that later. You can probably get away with just using your cell phone's camera, but with its limited resolution you may lose some shots.

GoPro

The most popular options for cockpit cameras are those from GoPro. If you have an older model it will probably be worth the expense to upgrade to one of the more recent offerings. Newer GoPros have higher resolution (4K) which makes it easier to zoom into and look at instrument readings. They can be mounted upside-down and will auto-correct to right-side-up. They have enhanced night vision. And, perhaps best of all, they can link to your phone so you can control them from an App to turn on and off as you need to as well as to help frame the shot. A drawback to many GoPro cameras is limited battery life that can limit your record time severely. I have a GoPro 7 Black which has a battery life of about 30 minutes, but the batteries can be swapped out.

GoPro 7 Black

- Weight: 4.1 oz., waterproof, rugged

- Sensor: 4.55 mm x 6.17 mm

- Resolution: Photos up to 10 mega pixels, video up to 4000 x 3000 at 60 frames per second

Conclusion: not too bad, better than most cell phones but not as good as . . .

DSLRs

I also use Digital Single Lens Reflex (DSLR) cameras because of the resolution and lens choice, but they almost always have limited record times. If the record time is greater than 30 minutes, the DSLR is no longer a camera, it is a camcorder which increases custom duty rates. Some DSLRs are even further limited due to internal heating.

Nikon D750

My primary DSLR is a Nikon D750, which I will use at night or when I really need minute details to be clear. Of the cameras shown here, it has the highest photo resolution and the best low level light performance. It is, however, the heaviest and most fragile. It is also important to note that it is a relatively difficult camera to use for video.

- Weight: 4 lbs. 3 oz. (as shown with a 14-24 mm f/2.8 lens)

- Sensor: 35.9 x 24.0 mm

- Resolution: Photos up to 24.3 mega pixels, video up to 1920 x 1080 at 60 frames per second

FujiFilm XT-3

My secondary DSLR is a FujiFilm XT-3, which I use when I need a DSLR but don't have the space to pack the Nikon. It is a step down in just about every regard, but it is relatively compact.

- Weight: 2 lbs. (as shown with a 18-35 mm f/2.8-4 lens)

- Sensor: 23.5 x 15.6 mm

- Resolution: Photos up to 26 mega pixels, video up to 4096 x 2160 at 60 frames per second

There is a lot of quality to be gained with a DSLR but they have a steep learning curve, they are expensive, and they take a lot of space. It isn't easy to mount one around the cockpit. If only there was a compromise between the GoPro and a DSLR. There is . . .

Point and Shoots

There used to be a popular genre of camera known as "point and shoots" because they allowed you the flexibility to just point the camera and shoot, as you would with a cell phone, but also gave you the ability to manually control much of the shot for much better results.

Sony RX100 Mark V

I usually have this camera with me when I fly, since it produces much better results than my cell phone and it is very compact. In its "auto" mode you do indeed just point it and press a button. But if that doesn't work out, it gives you the ability to change aperture, shutter speed, ISO, focus, etc.

- Weight: 8.47 oz.

- Sensor: 13.2 x 8.8 mm

- Resolution: Photos up to 20.2 mega pixels, video up to 1920 x 1080 at 50 frames per second

Each of the cameras listed so far have limited video record time. The DSLRs and the Point and Shoot are limited to 30 minutes. The GoPro might go a little longer. But for really long record times, I use a traditional camcorder.

Camcorders

The two primary advantages of a traditional camcorder are ease of use and record time.

Sony HXR NX80

- Weight: 3 lbs. 6 oz. (With high capacity battery and boom microphone)

- Sensor: 13.2 x 8.8 mm

- Resolution: 3840 x 2160, up to 120 frames per second

This is my favorite video camera, but it is bulky and takes some time to set up. I do, however, usually have another video camera handy . . .

Cell Phone or iPad Cameras

My iPhone isn't the newest but it isn't bad. And I almost always have one in the cockpit.

Apple iPhone 8

- Weight: 9 oz. (With waterproof case)

- Sensor: 4.8 x 3.6 mm

- Resolution: Photos up to 12 mega pixels, Videos up to 4K at 60 frames per second

A word about stats. I think there is some fuzzy math going on with the way manufacturers figure resolution, mega pixels, and lenses. Despite what the stats may tell you, the Nikon D750 has the best photo resolution and the Sony HXR-NX80 has the best video resolution of the cameras shown here. The GoPro is far worse, but easier to use and lighter. A cell phone camera is still pretty good and has one attribute the others probably lack: you almost always have it nearby. The worst part of a cell phone camera is the lens and if your shot doesn't come out, that is probably the culprit.

6

Things you wish you could do

I've always wanted to stick a GoPro on my aircraft's winglet, but of course that can never happen on my Gulfstream. Some manufacturers are certified with such mounts and others have had them added to a supplemental type certificate. Here's a view of Greg Bongiorno's Icon A5.