I don't mind admitting it, the KC-135A was one of the most difficult to fly airplanes — stick and rudder — I've ever touched. It had negative directional stability, had a pitch tolerance of 1/2 degree on takeoff at maximum weight, and many of the techniques required to fly it well were counter intuitive. The Air Force has since fixed everything with bigger engines and a yaw damper, but in 1985 the KC-135A was a beast to fly. That being said, if you knew what you were doing, it could be flown safely.

— James Albright

Updated:

2021-01-01

At the time of this crash I was flying an EC-135J, a Boeing 707, with almost identical flight characteristics. While we were about 50,000 pounds heavier and had larger, more powerful engines, the flight controls were about the same. We knew the stick and rudder skills required were high. The problem in the KC-135 tanker community was that the experience level was very low and many of their instructor pilots may have had fewer than 2,000 hours total flying time. This particular instructor pilot had just over 2,700 hours total flying time and was considered very experienced. He was in a tough situation though, and forgot the number one rule of aviation: fly the airplane.

At traffic pattern weights the KC-135 could fly a very long time with an engine out and no rudder input at all. But it would not fly if you got it too slow, especially with asymmetric thrust. The KC-135A did not have a flight data recorder and much of the post accident analysis is speculation. My take: the copilot bounced the airplane hard enough with enough yaw to take out an engine. The instructor took over and managed to get the airplane airborne but he got too slow. I flew over the crash site two days later. It wasn't much larger than the wing span of the airplane.

Just before the crash, back in Hawaii, we had a pilot smash in the wrong rudder and almost invert an airplane 200' above a pineapple field. We came up with our own solution for dealing with an engine failure: do nothing. We started teaching (and practicing) the following:

- At 200' AGL the instructor asks the student to place his feet on the floor and forbids the use of rudder until instructed. The instructor selects an outboard engine to fail, say #4, and braces the leg on the opposite side (in our example, the left leg) in case the student ignores the no rudder warning, and pulls that throttle to idle.

- As the thrust rapidly decays the operating engines lift that side's wing up and causes a bit of yaw. The instructor says "Level the wings with ailerons." After a few seconds: "we are still flying, still climbing, albeit sideways a little. Now look at the yoke, your left hand is down. Slowly step on the low hand until the yoke is level."

I've used the method ever since and have lost a few engines in that time. The method works.

Years later I was in a simulator course where the airplane's critical engine was the left and the instructors always failed the left engine on takeoff because that's what the check airman was going to do. I used my method and the instructor would say "not bad." My flying partner always got the rudder in so fast you never saw the nose track. "Perfect," the instructor would say as the student beamed at showing up the old man (me). "How can you be sure you got the correct rudder?" I asked. She said she felt the yaw. I talked the instructor into failing the right engine instead of the left without warning her. She mashed down on the right rudder, as always, and five seconds later we were dead, in simulator hell. She was furious and has never talked to me since. She is now an airline captain and I hope she never loses an engine.

Back to this crash . . . we gave our KC-135A instructor pilots nearly impossible tasks with this airplane. They had to teach 22-year old copilots how to deal with Dutch Roll in just ten sorties and the only way to do that was to let them really get the airplane close to out of control very low to the ground. A good instructor could get this pounded into these young pilots but had to take some risks doing so. Years after this crash the Air Force finally realized just how insane this is and installed yaw dampers and the entire problem went away. At the time of the crash, there were commercially available yaw dampers, stall warning systems, and stall barriers available for the KC-135A but the Air Force never installed them. If you ask me, this crash was caused by the Pentagon, not by a young copilot with barely 200 hours in his logbook or an instructor pilot with the nearly impossible task of training him.

I get emails from friends and families of this instructor pilot now and then, see below for just one of them. It sounds like he was a great pilot, officer, and person. The Air Force, for its part, got the "findings" (causes) exactly wrong. I'll save my editorial comment for the Probable Cause section, below.

1

Accident report

- Date: 27 AUG 1985

- Type: Boeing KC-135A Stratotanker

- Operator: United States Air Force - USAF

- Registration: 59-1443

- Fatalities: 7 of 7 crew

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airport: (Departure / Destination) Castle AFB, California (MER/KMER), United States of America;

- Airport: (Crash) Marysville-Beale AFB, CA (BAB/KBAB), United States of America

2

Narrative

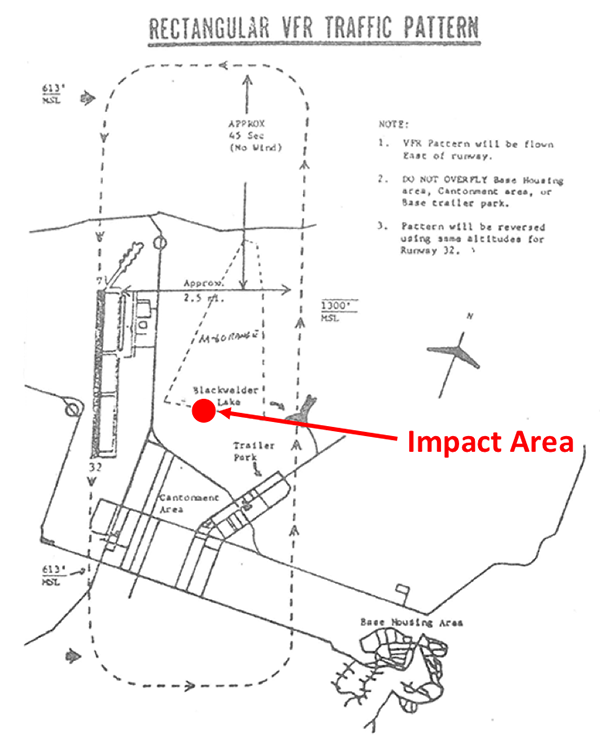

The flight was an S-2 student training sortie from Castle AFB. The crew consisted of an instructor team (instructor pilot, instructor navigator, and instructor boom operator) and a student crew (student aircraft commander, student copilot, student navigator, and student boom operator). After four and one-half hours of flight, the aircraft entered the Beale AFB traffic pattern for practice approaches. During the third practice approach, the number one engine pod contacted the runway. The aircraft executed a go-around and visual left-hand pattern. During the turn to downwind leg, the aircraft impacted the ground approximately one mile east of the runway on Beale AFB. The aircraft was destroyed and all crew members were fatalities.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, AF Form 711

- Instructor pilot's hours:

- Total flying time: 2713.6

- Instructor KC-135A: 687.9

- Student copilot's hours:

- Total flying time: 207.9

- KC-135A: 6.5

Source: USAF Mishap Report, Attachments G

Indications at time of electrical power loss

- Airspeed indicator: 152 KTS

- VVI: 1,100 ft/min descent

- ADI Unit "A": Roll - 95 deg left wg down, Pitch - 18 deg nose down

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page I-3

3

Analysis

The student copilot appeared to have lost lateral control while attempting to land, to the point the left (number one) engine contacted the runway. The Dutch roll of this airplane in the landing flare is excessive and in today's Air Force would be considered unsafe. An instructor had to let the student get to very large bank angles in an effort to teach the correct aileron technique.

- NUMBER ONE ENGINE, S/N 632462: This engine contacted the runway during an intended touch and go landing. Scrape marks found on the runway, along with a piece of the angle drive gearbox housing and approximately one-half of P/N 20351 (Ferrule-Accessory drive adapter), both recovered from the left side of the runway, verified that engine contact with the runway occurred. Post-impact evaluation of the engine revealed that it was rotating at very low revolutions per minute (RPM) and the turbine section had cooled considerably below normal operating temperature.

- NUMBER TWO ENGINE, S/N 632875: Engine was operating at high RPM on impact and sustained heavy rotational damage to both the compressor and turbine rotor assemblies.

- NUMBER THREE ENGINE, S/N 632741: Engine was operating at high RPM on impact and sustained heavy rotational damage to both the compressor and turbine rotor assemblies.

- NUMBER FOUR ENGINE, S/N 632055: Engine was operating at high RPM on impact and sustained heavy rotational damage to both the compressor and turbine rotor assemblies.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page J-3

Initial speculation pointed to a possible wrong-rudder input, but that can't be true because the aircraft appears to have achieved wings level flight.

Impact markings were found on the rudder balance panel arms indicating the rudder was approximately 9° right of neutral at impact.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page J-5, ¶6.

The aircraft was not equipped with a cockpit voice recorder or a flight data recorder, but it appears from photographic evidence and from the mishap report:

- The student copilot landed with enough Dutch roll to cause the left engine to contact the runway with enough force to dislodge parts and cause the engine to stop operating. (Derived from the engine parts on the ground and the condition of each engine at impact.)

- The instructor pilot took the aircraft and successfully applied full power on the other three engines, applied the correct rudder, and got the airplane flying away from the ground in wings level flight. (Derived from a photograph.)

- The instructor pilot executed a very aggressive left closed pattern. (Derived from the impact area which was halfway between the runway and a normal VFR downwind pattern.)

- The instructor got the nose too high, ran out of speed for the asymmetric condition, and stall the aircraft. (From the mishap report.)

Of course all of this begs the question: why? To which I would say there are two 'whys' to answer:

- Why did the instructor pilot allow the student to lose control of the aircraft in the landing? The answer is because that was his job. The Air Force had flown this 26-year old aircraft that was prone to excessive Dutch roll even though commercially available yaw dampers were available for at least 20 years. They had done so, obviously, to save money. But not so obviously because they could. The mentality of the Air Force at the time was to accept one or two tanker losses every year as "a cost of doing business."

- Why did the instructor pilot turn so aggressively during the go around? This answer is less clear but we can speculate that he was angry at having let the student hit an engine pod. There had never been, as far anyone acknowledged, any similar incident while training new KC-13A copilots. There were a lot of war stories, to be sure. But if there were similar incidents, they were not publicly acknowledged. He must have known that his stellar reputation to that point was going to be tarnished and his Air Force career was ostensibly over. The instructor must also have felt confident enough in his abilities to keep the aircraft within the flight envelope, even under the asymmetric condition.

4

Cause

Air Force mishap reports were written back then in what was supposed to be a sterile, just the facts, manner but had to emphasize the word, "fail." Somebody (not something) had to have failed for the mishap to have occurred. I've added several findings of my own because they serve us surviving pilots a cautionary tale. We have to assess the shortcomings of our airplanes and our operators before we can hope to address our ability to fly flawed machinery.

- FINDING ZERO (CAUSE): The Air Force failed to install commercially available yaw dampers on the KC-135A fleet, even though they had been available for at least 20 years. They instead required KC-135A pilots to learn difficult Dutch roll compensation techniques that would take most pilots considerable experience to master.

- FINDING ONE: The copilot, while undergoing initial qualification training, induced lateral instability while on short final for a touch-and-go landing.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page T-34.

- FINDING ONE POINT ONE (CAUSE): The Air Force placed this young pilot in a situation for which he had not been adequately trained. None of his previous aircraft had the same lateral instability problem as the KC-135A and the simulator was not up to the task of teaching the required Dutch roll techniques.

- FINDING TWO (CAUSE): The instructor pilot failed to adequately intervene.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page T-34.

- FINDING TWO POINT ONE (CAUSE): The Air Force required its KC-135A instructor pilots to allow unqualified pilots fly the aircraft very near the margins of controlled flight in an attempt to teach Dutch roll techniques.

- FINDING THREE: The number one engine contacted the runway.

- FINDING FOUR: While the instructor pilot executed a go-around, the number one engine flamed out and caught fire.

- FINDING FIVE (CAUSE): The instructor pilot, probably because of an inflight engine fire, violated technical order guidance by executing an aggressive, close-in, climbing left turn with only three engines operating. The turn was initiated prior to completing the go-around procedure and below a safe airspeed (estimated 130 KIAS).

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page T-34.

- FINDING FIVE POINT ONE (CAUSE): The Air Force failed to emphasize with its KC-135A instructor force the need to treat asymmetric flight with the needed caution and the primary objective of a wings level, controlled climb. After this crash, the Air Force instituted a very good asymmetric flight course for KC-135A pilots.

- FINDING SIX (CAUSE): On the crosswind leg, the instructor pilot placed the aircraft in a nose high climbing attitude which allowed the airspeed to dissipate.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page T-34.

- FINDING SIX POINT ONE (CAUSE): The Air Force failed to install commercially available stall warning and barrier systems that would have warned the instructor pilot about the impending stall.

- FINDING SEVEN: The aircraft stalled, yawed, and rolled left.

- FINDING EIGHT: The aircraft impacted the ground in a steep nose low attitude with ninety-five degrees of bank and exploded.

- FINDING NINE: The aircraft was destroyed and all seven crew members were fatalities.

Source: USAF Mishap Report, page T-34.

5

Postscript

Sir,

I am a retired Major, Instructor Navigator on KC-135A/Q/R.

I served at Altus AFB, OK with the Instructor Pilot, Major _____, who was flying the mishap aircraft #59-1443 at Beale AFB, CA on 27 Aug 1985.

He was one of the closest friends I ever had in my life.

After Altus, I flew KC-135 Q models with the Beale Bandits out of Beale AFB, refueling the SR-71 Blackbird and _____ became an Instructor Pilot at Castle AFB, CA.

At Beale, I met another lifelong friend who was an Instructor Navigator.

In May, 1985, I was transferred to the staff at 8th Air Force HQ at Barksdale AFB, LA, and my Beale friend was transferred to Castle as an Instructor Navigator.

Late in August my Beale buddy called me from Castle and asked if I knew _____. I said yes and he said _____ was killed while training at Beale.

In the same building as my staff office in 8th Air Force HQ was the 8th Air Force Safety office. I prevailed upon a friend in the Safety office to let me read the accident report.

I wish I hadn’t, but your description of the mishap is accurate.

HERE IS THE RUB.

Beale’s north/south runway is 15, true heading 147.3 degrees. The variation at Beale is 14 degrees east, so that makes a compass heading of 133.

When I flew as crew or instructor at Beale we always briefed that, if a major problem occurred when taking off to the south, we would fly straight ahead, declare an emergency, and request approach to Castle AFB, 130 NM to the south. If we maintained a compass heading of 133 we would soon end up in the Sierra Nevada mountains, so, we said, “Fly due south and call Castle”.

I believe that the mishap aircraft took off from Castle, flew its training mission and was using the less congested airspace at Beale for touch and go training.

I doubt if the Castle crew, including 4 rookies, knew of the Beale briefed emergency procedures.

If I recall the accident report, _____ declared an emergency and asked for a closed pattern to return to RWY 15 (I am not sure of that, although they crashed on downwind).

The terrain at Beale rises 113 feet immediately east of the runway within the airfield boundary.

I believe _____ was flying with a rookie crew on their first transition flight into the type. The brand new copilot was flying his first attempted landing (as I recall).

They dragged the #1 engine which caught fire.

_____ was a go-getter and had little help on the flight deck. It seems he turned into a dead or failing engine and let his airspeed fall off.

There is a photograph of the plane just before impact at about 90 degrees left roll and maybe 40 degrees nose low.

One chilling item I wish I had not read was that the aircraft impacted at the pilot’s #2 window, right where _____ was sitting, and that the seventh crew member was identified by process of elimination. (I suffered from about a year of PTSD over that statement and the loss of the Challenger space shuttle in January 1986).

I hope this commentary is of some value and I am glad to get it off my chest at this late date.

_____

Major, USAF (Ret.)

References

(Source material)

USAF Mishap Report, 27 Aug 1985, KC-135A, 59-1443, Approx 1 mile east of Rwy 15, on Beale AFB, CA, 26 Sep 1985.