If you've been blessed by flying only stable aircraft, much of this may be lost on you. If you are currently flying an aircraft that often misbehaves, you need to read this. In either case, knowing what makes an airplane stable helps to deal with the times it isn't.

— James Albright

Updated:

2024-03-17

Having grown up in two aircraft that had negative directional stability, the KC-135A and the Boeing 707, I became an expert at dealing with Dutch roll. Most modern aircraft have no Dutch roll tendency at all, due either to superb design or superb yaw dampers. If your aircraft has a yaw damper, or more than one in some cases, you might want to be familiar with how to get out of a Dutch roll when the yaw damper isn't working.

3 — Longitudinal dynamic stability

1

Static stability

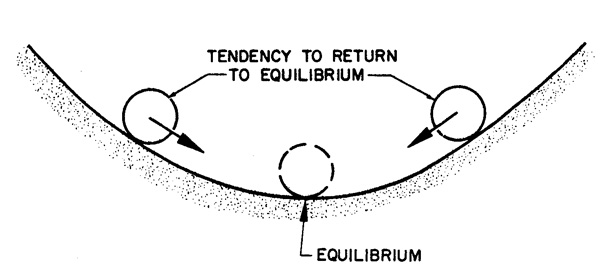

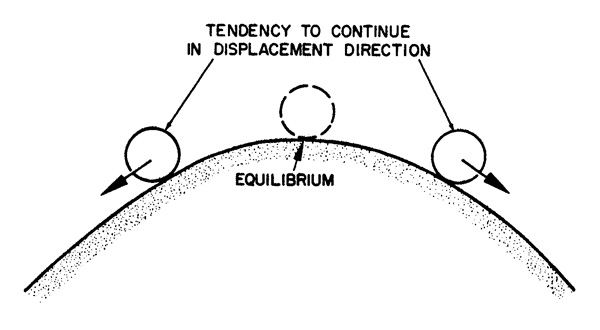

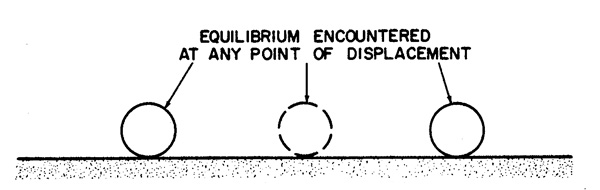

The static stability of a system is defined by the initial tendency to return to equilibrium conditions following some disturbance from equilibrium. Only its initial tendency is considered.

Source: Hurt, pg. 245

Imagine a marble in a bowl which is perfectly rounded, inside and out. The marble tends to gravitate to the bottom and stay there. If the marble is pushed to one side, it will roll back to the center, perhaps overshooting but eventually returning to its original state in the center. The marble is said to have positive static stability.

I've heard that the U-2 has superb longitudinal stability. If you trim the airplane and push the yoke forward or aft, it will easily return itself to the original pitch. It has good static pitch stability.

Now consider the same marble atop the same bowl inverted. The marble sits up there precariously and even the slightest force will cause it to move away from the center, its state of equilibrium. Not only does the marble move, it continues to move. The marble is said to have negative static stability.

The early KC-135As had terrible Dutch roll tendencies. If you had the aircraft in trimmed, level flight and let go of the ailerons, they would induce an oscillating roll on their own. The airplane had negative lateral stability.

A final case of static stability places our marble on a perfectly flat, frictionless surface in a vacuum. (Ridiculous, I know, but that's how engineering professors think.) If you push the marble in any direction, it will move and continue to move.

2

Dynamic stability

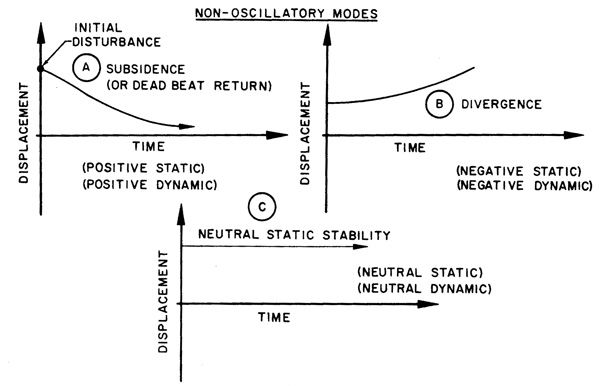

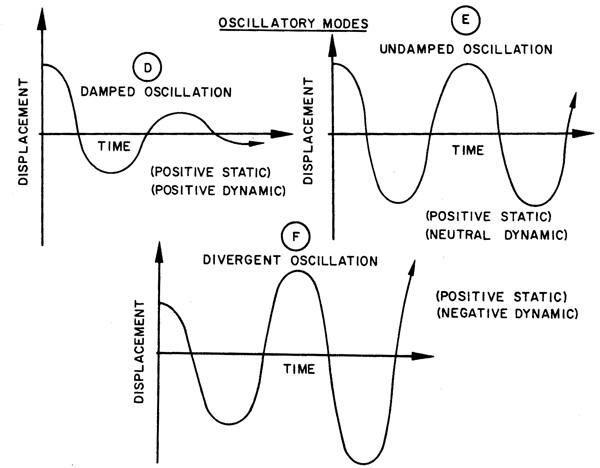

While static stability concerns the initial tendencies of an object, dynamic stability concerns the resulting motion over a span of time.

If the initial tendencies tend to decrease, the object is said to have positive dynamic stability. If they increase, it is negative dynamic stability. If they stay the same, of course, that is neutral dynamic stability.

If the dynamic motion is in agreement with the static tendency, you have a non-oscillatory stability.

If the motion oscillates but gets smaller over time, you have positive static and dynamic stability.

If the motion oscillates but gets greater with time, although you had positive static stability this was only the initial tendency. You will have a negative dynamic stability.

If the motion oscillates without end at the same magnitude, your initial static stability as been countered with negative dynamic stability.

3

Longitudinal dynamic stability

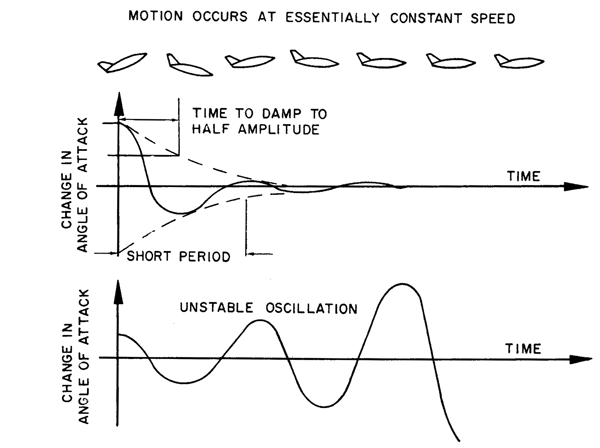

You have dynamic stability if the amplitude of any oscillations dampen out with time. These are further classified as "stick fixed" or "stick free." A stick fixed condition is where the controls do not move freely in response to air loads. Most aircraft with hydraulically actuated controls are stick fixed and should exhibit greater stability. A stick free airplane is one that will allow control movement in response to air loads, gusts, or other stimuli.

phu·goid [fyoo-goid] adjective Aerospace. Of or pertaining to long-period oscillation in the longitudinal motion of an aircraft, rocket, or missile.

Origin:

1905–10; irregular < Greek phyg ( ḗ ) flight + -oid

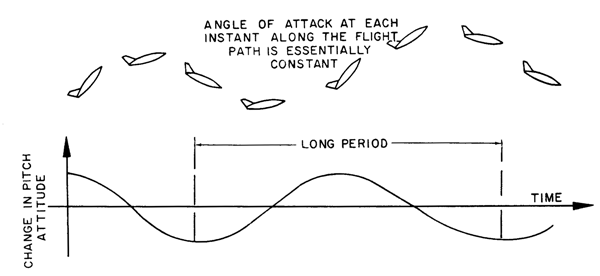

The phugoid oscillation is one where the airspeed, pitch, and altitude of the airplane vary widely, but the AOA remains nearly constant. The motion is so slow that the effects of inertia forces and damping forces are very low. The whole phugoid can be thought of as a slow interchange between kinetic and potential energy.

Source: Dole, pg. 256

The short period mode is always heavily damped and, if no pilot inputs are made, the oscillations will dampen out rapidly. The short periods correspond closely with the normal pilot response time, and there is the possibility than any attempt to dampen out these oscillations may actually reinforce them and produce instability. This lead to pilot induced oscillations (PIO), which can destroy an aircraft in a matter of a few seconds. Should such an oscillation develop, usually as a result of sharp gusts, the best procedure is to release the controls and allow the natural damping of the aircraft to take over. A positive control force will also eliminate the PIO. The impulse to steady the aircraft should be avoided in all cases.

Source: Dole, pg. 256

4

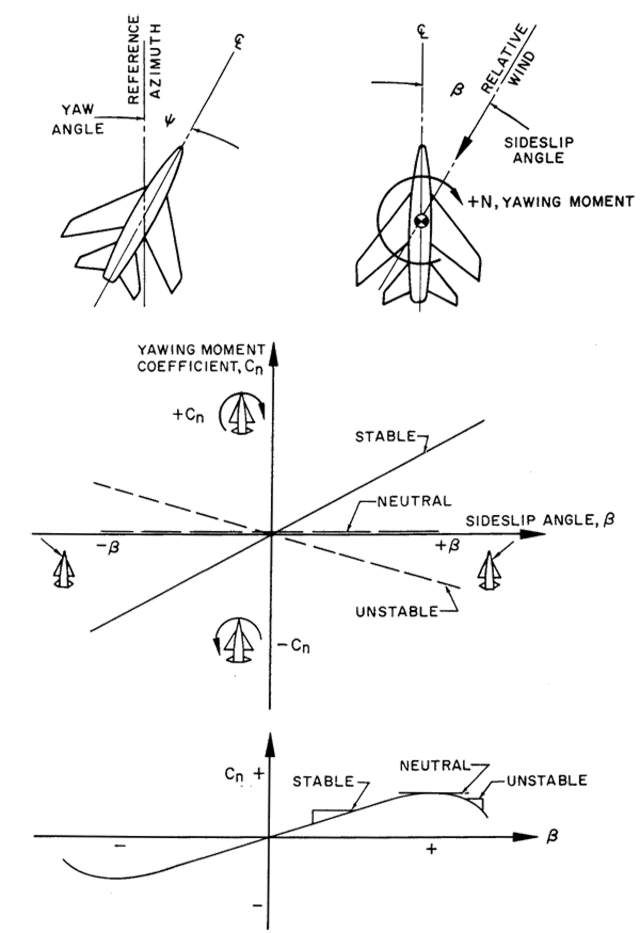

Directional static stability

An airplane is said to have positive directional stability if it is trimmed for non-sideslip flight, is then subjected to a sideslip condition, and reacts by turning into the new relative wind so that the sideslip angle is reduced to zero. On the other hand, if the airplane reacts to the sideslip by turning away from the new relative wind, thus increasing the sideslip angle, the airplane has negative directional stability. If no reaction results from sideslip, the airplane is said to have neutral directional stability.

Source: Dole, pg. 262

For an example of how this can go wrong, see KC-135A 59-1443.

5

Dutch roll

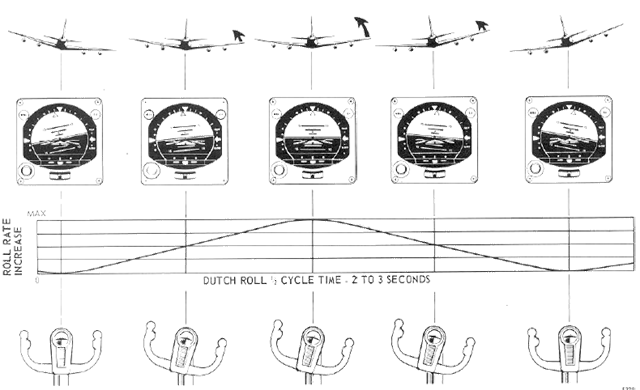

A Dutch roll is a combination of yawing and rolling motions where the rolling motion continuously reverses itself with less noticeable yaw moments unless the rolling is significant. It is better called "oscillatory stability." The aircraft's spiral stability — its tendency to return to wings level when the ailerons are released — and its oscillatory stability are always in conflict. One factor makes the aircraft maneuverable, the other makes it stable.

Roll Tendency

- A wing produces lift by accelerating the air which passes over the top surface to a higher speed than that which passes under the bottom surface. The greater the difference between these two speeds the higher to difference in pressure, hence the larger the lift vector.

- Because the local speed of the upper surface air is higher than the free stream speed — a good bit higher where the camber is marked — it is clear that this airstream will become sonic before the effect first become apparent free stream reaches the sonic value. At this speed local shock waves are formed on the wing and compressibility effects become apparent; the drag increases, buffeting is felt and changes in lift and the position of the centre of pressure occur which, at a fixed tail angle, are reflected as changes in pitch. The Mach number at which these compressibility effects first become apparent is the critical Mach number; all other parameters aside, this can be quite low for a straight wing, around 0.7 Mach number.

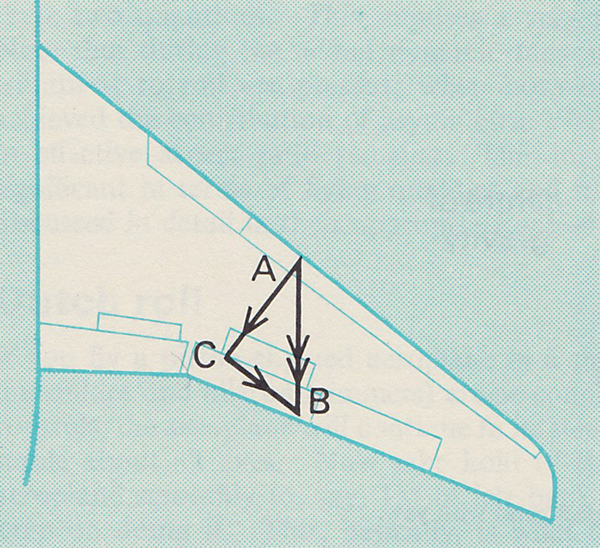

- By sweeping a wing significantly, it will be remembered, the velocity vector normal to the leading edge is made less than the chord wise resultant. In [the figure] AC is shorter than AB. As the wing is responsive only to the velocity vector normal to the leading edge, for a given Mach number the effective chord wise velocity is reduced (in effect the wing is persuaded to believe that it is flying slower than it really is). This means that the airspeed can be increased before the effective chord wise component become sonic and thus the critical Mach number is raised.

Source: Davies, pg. 96-99

- When a straight winged aeroplane is yawing it also rolls. This is because the inside wing is effectively slowed down and the outside wing is effectively speeded up, thus unbalancing the V terms in the lift formulae for each wing taken separately. The lift is unbalanced and the aeroplane rolls.

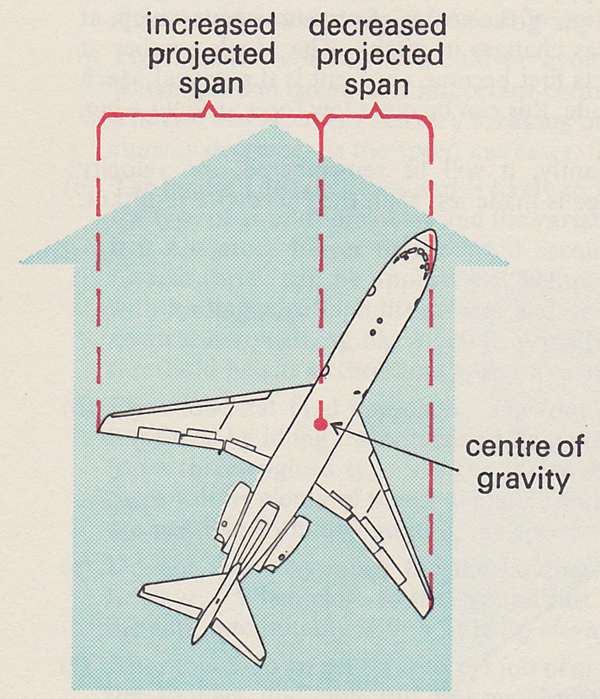

- On a swept wing aeroplane this effect is compounded because the angle of slip effectively alters the sweep of the two wings. The faster (outside) wing becomes less swept and generates increased lift at a constant incidence because of the increase in effective aspect ratio. This is because the projected span of that wing is increased. The slower (inside) wing becomes even more swept and loses lift at a constant incidence for the same basic reason. This further unbalances the lift and the rolling tendency is markedly increased. Reference to [the figure] shows that the outside wing has a much greater effective aspect ratio than the inside wing, and is also traveling faster.

- This imposes a very marked roll on the aeroplane. Note that during the actual dynamic manoeuvre of yawing both the contributions to roll are present; when however a steady state of sideslip is achieved the contribution of asymmetric V2 disappears and only the change in effective aspect ratio remains. This marked roll with yawing is very significant in terms of flying qualities.

Stable Dutch Roll

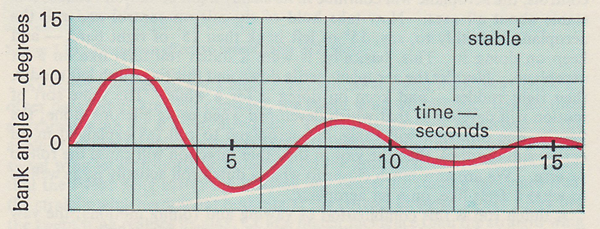

- Oscillatory stability, that is stable Dutch roll, can now be defined as the tendency of an aeroplane when disturbed, either directionally or laterally, to damp out the ensuing yawing/rolling motion and return to steady flight.

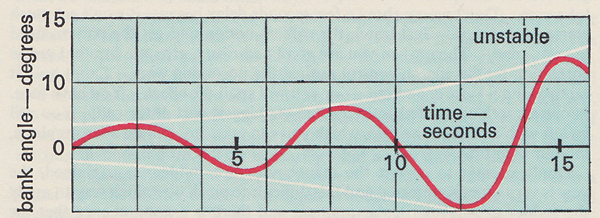

- When an aeroplane is yawed it rolls. The fin and rudder then oppose the yaw, slow it down and stop it, and return the aircraft towards straight flight. If the fin and rudder are big enough, the second yaw and roll are less than the first and each excursion gets progressively smaller until the motion damps right out. If, however, the fin and rudder are too small the second yaw and roll are bigger than the first, each overswing gets progressively larger and the motion becomes divergent, i.e., unstable. Although the initial yaw is the trigger for this misbehaviour it is the rolling motion, in most aeroplanes, which is most noticeable to the pilot; this is why the rolling behavior is used as the main parameter in measuring Dutch roll.

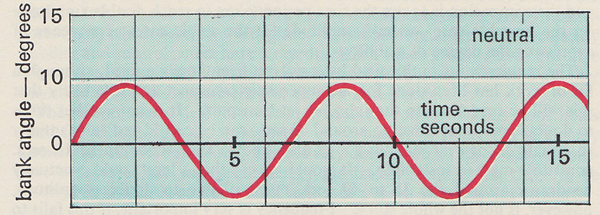

- Like any other form of stability, oscillatory stability can be positive, neutral, or negative, which is to say the Dutch roll can be stable, neutral, or unstable.

- Positive Dutch roll is basically safe because the aeroplane, left alone, will either quickly or more slowly, finally bring itself under control.

Source: Davies, pg. 100

Neutral Dutch Roll

Neutral stability is safe (enough) because it won't get worse, but undesirable because, if the amplitude is large, or the frequency is small, the aeroplane is tiring and tedious to fly.

Source: Davies, pg. 101

Negative Dutch Roll

Negative stability is potentially dangerous because sooner or later, depending on the rate of divergence, the aeroplane will either get out of hand or demand a constant very high level of skill and attention to maintain control. The unstable case, however, needs to be qualified in this way: if the divergence is very slow then it can be tolerated. To the pilot there is no significant difference between a Dutch roll which is only very, very slowly divergent over one which is truly neutral.

Source: Davies, pg. 101

Manually Damping Dutch Roll

For most pilots, manually damping a Dutch roll is either a theoretical exercise or a simulator demonstration. For many of us, however, it was a daily survival drill. So here is the theory followed by the actual procedure for the Air Force Boeing 707 (EC-135C).

The control of a divergent Dutch roll is not difficult so long as it is handled properly. Let us assume that your aeroplane develops a diverging Dutch roll. The first thing to do is nothing — repeat nothing. Too many pilots have grabbed the aeroplane in a rush, done the wrong thing and made matters a lot worse. Don't worry about a few seconds delay because it won't get much worse in this time. Just watch the rolling motion and get the pattern fixed in your mind. Then, when you are good and ready, give one firm but gentle correction on the aileron control against the upcoming wing. Don't hold it on too long — just in and out — or you will spoil the effect. You have then, in one smooth controlled action, killed the biggest part of the roll. You will be left with a residual wriggle, which you can take out, still on ailerons alone, in your own time.

Source: Davies, pg. 102

Manual damping of Dutch roll is accomplished with the lateral controls only. As a first approximation, use a control wheel input roughly equal to the degree of oscillation. For example, if the bank angle oscillations are +/- 10°, use about 10° of control wheel. Lateral control inputs should not be large and should be centered quickly as the rolling motion stops. If the input is held too long, it may excite another large oscillation in the opposite direction. Several cycles may be required to damp out Dutch roll. The next lateral control input should be delayed until the start of the next bank oscillation and then be applied to stop the rising wing, quickly centering the wheel as the roll stops.

Source: Technical Order 1C-135(E)C-1, pg. 6-15

Flying the old KC-135A and EC-135J, both without yaw dampers, it seemed it took quite a while for most pilots to figure out how to dampen the aircraft's natural tendency to Dutch Roll. While the basic C-135 airframe was the precursor of the venerable Boeing 707, its Dutch Roll seemed worse. Later versions of the Boeing 707 had yaw dampers, but those early models did not. How did early Boeing 707 pilots deal with Dutch Roll? They also struggled, but they too eventually got it. I've heard the 707's longer fuselage and taller tail made the Dutch Roll more manageable. but not by much:

Ground school lasted six weeks. After 707 systems came an operations specifications course, and then a class on Pan Am weight and balance procedures and dispatch problems and aircraft performance.

Finally they were ready to fly.

That was supposed to be the easy part. Flying was flying, Martinside had always believed. If you could fly, say, an A-4 off carriers as he had done, you could fly anything. It was just a matter of adjustment.

One star-filled night he found himself wallowing through the sky over Stockton, California, in the right seat of a Boeing 707. Despite his best efforts with the steering-wheel-like control yoke and the rudder pedals, he could not make the damn airplane fly straight. The beast wallowed, yawing in a sickening nose-left, right-wing-down. They called it a "Dutch roll" -an aerodynamic phenomenon peculiar to swept-wing transports like the 707. Forty years earlier the condition had been identified by engineers and named after an oscillating style of ice skating imported from the Netherlands.

"You stop it like this," said Forster, the instructor. He applied a rightward jab to the yoke, then returned it to neutral. The rolling ceased. "Whenever it starts, just give it one of these," Forster explained, jabbing the yoke to the left. "It's easy."

Martinside tried it. It wasn't easy. After several tries he learned to anticipate the big jet's tendency to swing its nose like a pendulum. The trick was to anticipate the yaw, then stop it with little, short jabs, as Forster had just done.

Source: Skygods, p. 68

Robert Gandt knows of what he speaks, having flown all sorts of Boeing airliners, but his account displays the normal explanation, "you stop it like this." For someone who had never stopped Dutch Roll, the explanation fails to inform. We used to train the technique by illustrating the rocking motion of the wings by spreading a hand's fingers to mimic the wing and rocking it slowly to one side. With the other hand we would show the actions you would take with the yoke. It all happens so fast that few pilots get it on the first flight and for many it takes months to master. But most pilots eventually do. And once they do, they also forget the struggle. It becomes almost second nature.

6

A brief history lesson

Nothing related to the Wright brothers has created more confusion, controversy, discussion, and at times vitriolic argument than questions of equilibrium, stability, and control. There is fairly general agreement that the Wrights' experience with bicycles taught them the virtue of control. The bicycle is unstable without active control by the rider. Thus the Wrights were not deterred by the possibility of an unstable vehicle which could nevertheless be successfully operated with practice, providing the means existed for proper control. It is also clear that control was always a central issue during development of their aircraft.

What is by no means evident is the extent to which the Wrights inadvertently produced unstable aircraft. They certainly refused to follow their contemporaries who were preoccupied with the goal of inventing an intrinsically or automatically stable airplane. On the other hand, it is not necessary that an airplane be unstable to be controllable.

The Wrights were the first to place the smaller horizontal surface forward-the canard configuration. They knew very well the history of the aft horizontal tail. In particular, they were aware that, as perceived by Cayley in 1799 and shown by Penaud in 1872, an aircraft with an aft tail can be made longitudinally stable. Moreover, early in their program, in 1899 with the kite, and in 1900 with the man-carrying kite/ glider, they experimented successfully with an aft tail. They knew that the configuration could easily be made stable. There is no doubt that they chose the canard because of fear, first expressed by Wilbur, that the aft tail carried with it an intrinsic danger. What worried them was the possible inability to recover from a stall, due to loss of lift induced by a vertical gust, or by the pilot upon raising the nose too far. That had been the cause of Lilienthal's death in 1896.

Thus the choice of the canard configuration, the most distinctive feature of the Wright aircraft, was not based on sound technical grounds of stability. It was rather a matter of control in pitch, especially under extreme conditions. In fact, the Wrights did not understand stability in the precise sense that we do now. The reason is fundamental: nowhere in their work did they consider explicitly the balance of moments. They shared that ignorance with all others trying to build aircraft at that time. So strictly, whether their aircraft were stable or unstable was an accidental matter.

Source: Wolko, pp. 21 - 22

It can be said that stability is inversely proportional to maneuverability.

References

(Source material)

Davies, D. P., Handling the Big Jets, Civil Aviation Authority, Kingsway, London, 1985.

Dole, Charles E., Flight Theory and Aerodynamics, John Wiley & Sons, Inc, New York, NY, 1981.

Gandt, Robert, Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am, Wm. Morrow Company, Inc., New York, 2012

Hurt, H. H., Jr., Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators, Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., New York NY, 2012.

Technical Order 1C-135(E)C-1, EC-135C Flight Manual, USAF Series, 15 February 1966.

Wolko, Howard S., The Wright Flyer: An Engineering Perspective, National Air and Space Museum, 1987