I think of this crash every time I get on a commuter airliner as a passenger. First, what really happened:

- Two inexperienced pilots put themselves on duty after long commutes and inadequate rest, sleeping either on an airplane while commuting or in the airline's pilot lounge.

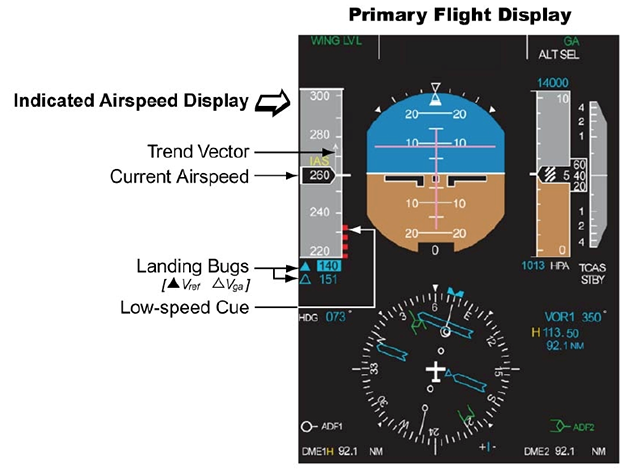

- The pilots activated a VREF switch used for icing conditions that raised the pilot display low speed cues and stick shaker speed.

- The pilots were disengaged during the approach, talking idly while failing to notice the low speed cues and getting behind in normal briefings and approach callouts.

- When the stick shaker went off, because of the VREF switch, the aircraft was a good 20 knots above stall speed.

- The captain pulled up aggressively and put the airplane into a stall.

- The first officer retracted the flaps, deepening the stall.

- The aircraft fell almost straight down, killing all on board and one on the ground.

— James Albright

Updated:

2015-03-14

Had the pilot, at any time until just about the last few moments, simply pushed forward on the controls, the airplane would have recovered. Some make the case that these pilots would have performed better if not fatigued. Perhaps. But a more experienced or better trained pilot would have never got the airplane into that situation and would not have put the airplane into the stall after the stick shaker went off.

I think the professional aviator class is filled with pilots that don't have a basic understanding of aerodynamics and why airplanes actually fly, how to get an airplane out of a stall, or the need to focus on the task at hand when flying an airplane:

- Aerodynamics — Not everyone who drives a car understands what is going on between the gas pedal and the tires but every pilot should know the difference between the relative wind and the chordline of a wing. See Lift for more about this.

- Stall Recovery — When a highly cambered wing is stalled there is only one way to get it out of the stall and years of simulator practice trying to hold every inch of altitude needs to be unlearned. See Angle of Attack for more about AOA. As a result of this mishap the stall recovery training most American pilots receive is changing. See Stall Recovery for more about this.

- Sterile Cockpit — Though the NTSB report doesn't spend much time on it, these pilots chatted idly while on an instrument approach and failed to notice the many cues they had telling them their speed was heading south. See Sterile Cockpit for more on this topic.

But there is one more factor that I think everyone has missed. When pilots who have never stalled a large airplane are trained exclusively in simulators, having an abnormal situation outside of the box can come as a shock. When in a panic, our brains often jump to an instinctual reaction (pull back on the yoke) and fail to think things through. The best way to deal with this is to desensitize oneself against the fear in a real airplane. More about this: Panic.

1

Accident report

- Date: 12 FEB 2009

- Time: 22:17

- Type: de Havilland Canada DHC-8-400 Q400

- Operator: Colgan Air

- Registration: N200WQ

- Fatalities: 4 of 4 crew, 45 of 45 passengers, plus 1 ground fatality

- Aircraft Fate: Destroyed

- Phase: Approach

- Airport: (Departure) Newark-Liberty International Airport, NJ (EWR) (EWR/KEWR), United States of America

- Airport: (Destination) Buffalo Niagara International Airport, NY (BUF) (BUF/KBUF), United States of America

2

Narrative

- The home base of operations for both the captain and the first officer was Liberty International Airport (EWR), Newark, New Jersey. On February 11, 2009, the captain had completed a 2-day trip sequence, with the final flight of the trip arriving at EWR at 1544. Also that day, the first officer began her commute from her home near Seattle, Washington, to EWR at 1951 Pacific standard time (PST), arriving at EWR (via Memphis International Airport [MEM], Memphis, Tennessee) on the day of the accident at 0623. The captain and the first officer were both observed in Colgan's crew room on February 12 before their scheduled report time of 1330. The flight crew's first two scheduled flights of the day, from EWR to Greater Rochester International Airport (ROC), Rochester, New York, and back, had been canceled because of high winds at EWR and the resulting ground delays at the airport.

- The company dispatch release for flight 3407 was issued at 1800 and showed an estimated departure time of 1910 and an estimated en route time of 53 minutes. The airplane to be used for flight 3407, N200WQ, arrived at EWR at 1854. A first officer whose flight arrived at EWR at 1853 saw, as he exited his airplane, the flight 3407 captain and first officer walking toward the accident airplane. The airplane's aircraft communications addressing and reporting system (ACARS) showed a departure clearance request at 1930 and pushback from the gate at 1945. According to the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) recording, the EWR ground controller provided taxi instructions for the flight at 2030:28,7 which the first officer acknowledged.

- About 2041:35, the first officer stated, "I'm ready to be in the hotel room," to which the captain replied, "I feel bad for you." She continued, "this is one of those times that if I felt like this when I was at home there's no way I would have come all the way out here." She then stated, "if I call in sick now I've got to put myself in a hotel until I feel better ... we'll see how ... it feels flying. If the pressure's just too much ... I could always call in tomorrow at least I'm in a hotel on the company's buck but we'll see. I'm pretty tough." The captain responded by stating that the first officer could try an over-the-counter herbal supplement, drink orange juice, or take vitamin C.

- The CVR recorded the tower controller clearing the airplane for takeoff about 2118:23. The first officer acknowledged the clearance, and the captain stated, "alright cleared for takeoff it's mine." According to the dispatch release, the intended cruise altitude for the flight was 16,000 feet mean sea level (msl). The flight data recorder (FDR) showed that, during the climb to altitude, the propeller deice and airframe deice equipment were turned on (the pitot static deicing equipment had been turned on before takeoff) and the autopilot was engaged.

- The airplane reached its cruising altitude of 16,000 feet about 2134:44. The cruise portion of flight was routine and uneventful. The CVR recorded the captain and the first officer engaged in an almost continuous conversation throughout that portion of the flight, but these conversations did not conflict with the sterile cockpit rule, which prohibits nonessential conversations within the cockpit during critical phases of flight. About 2149:18, the CVR recorded the captain making a sound similar to a yawn. About 1 minute later, the captain interrupted his own conversation to point out, to the first officer, traffic that was crossing left to right. About 2150:42, the first officer reported the winds to be from 250° at 15 knots gusting to 23 knots; afterward, the captain stated that runway 23 would be used for the landing.

- About 2153:40, the first officer briefed the airspeeds for landing with the flaps at 15° (flaps 15) as 118 knots (reference landing speed [Vref]) and 114 knots (go-around speed [Vga]), and the captain acknowledged this information. About 2156:26, the first officer stated, "might be easier on my ears if we start going down sooner." About 2156:36, the captain instructed the first officer to "get discretion to twelve [thousand feet]." Less than 1 minute later, a controller from Cleveland Center cleared the flight to descend to 11,000 feet, and the first officer acknowledged the clearance.

- About 2203:38, the Cleveland Center controller instructed the flight crew to contact BUF approach control, and the first officer acknowledged this instruction. The first officer made initial contact with BUF approach control about 2203:53, stating that the flight was descending from 12,000 to 11,000 feet with automatic terminal information service (ATIS) information "romeo,"11 and the approach controller provided the airport altimeter setting and told the crew to plan an instrument landing system (ILS) approach to runway 23.

- About 2204:16, the captain began the approach briefing. About 2205:01, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to descend and maintain 6,000 feet, and the first officer acknowledged the clearance. About 30 seconds later, the captain continued the approach briefing, during which he repeated the airspeeds for a flaps 15 landing. FDR data showed that the airplane descended through 10,000 feet about 2206:37. From that point on, the flight crew was required to observe the sterile cockpit rule.

- About 2207:14, the CVR recorded the first officer making a sound similar to a yawn. About 2208:41 and 2209:12, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to descend and maintain 5,000 and 4,000 feet, respectively, and the first officer acknowledged the clearances. Afterward, the captain asked the first officer about her ears, and she indicated that they were stuffy and popping.

- About 2210:23, the first officer asked whether ice had been accumulating on the windshield, and the captain replied that ice was present on his side of the windshield and asked whether ice was present on her windshield side. The first officer responded, "lots of ice." The captain then stated, "that's the most I've seen—most ice I've seen on the leading edges in a long time. In a while anyway I should say." About 10 seconds later, the captain and the first officer began a conversation that was unrelated to their flying duties. During that conversation, the first officer indicated that she had accumulated more actual flight time in icing conditions on her first day of initial operating experience (IOE) with Colgan than she had before her employment with the company. She also stated that, when other company first officers were "complaining" about not yet having upgraded to captain, she was thinking that she "wouldn't mind going through a winter in the northeast before [upgrading] to captain." The first officer explained that, before IOE, she had "never seen icing conditions ... never deiced ... never experienced any of that."

- About 2212:18, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to descend and maintain 2,300 feet, and the first officer acknowledged the clearance. Afterward, the captain and the first officer performed flight-related duties but also continued the conversation that was unrelated to their flying duties. About 2212:44, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to turn left onto a heading of 330°. About 2213:25 and 2213:36, the captain called for the descent and approach checklists, respectively, which the first officer performed. About 2214:09, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to turn left onto a heading of 310°, and the autopilot's altitude hold mode became active about 1 second later as the airplane was approaching the preselected altitude of 2,300 feet. The airplane reached this altitude about 2214:30; the airspeed was about 180 knots at the time.

- About 2215:06, the captain called for the flaps to be moved to the 5° position, and the CVR recorded a sound similar to flap handle movement. Afterward, the approach controller cleared the flight crew to turn left onto a heading of 260° and maintain 2,300 feet until established on the localizer for the ILS approach to runway 23. The first officer acknowledged the clearance.

- The captain began to slow the airplane less than 3 miles from the outer marker to establish the appropriate airspeed before landing. According to FDR data, the engine power levers were reduced to about 42° (flight idle was 35°) about 2216:00, and both engines' torque values were at minimum thrust about 2216:02. The approach controller then instructed the flight crew to contact the BUF air traffic control tower (ATCT) controller. The first officer acknowledged this instruction, which was the last communication between the flight crew and air traffic control (ATC). Afterward, the CVR recorded sounds similar to landing gear handle deployment and landing gear movement, and the FDR showed that the propeller condition levers had been moved forward to their maximum RPM position and that pitch trim in the airplane-nose-up direction had been applied by the autopilot.

- About 2216:21, the first officer told the captain that the gear was down; at that time, the airspeed was about 145 knots. Afterward, FDR data showed that additional pitch trim in the airplane-nose-up direction had been applied by the autopilot and that an "ice detected" message appeared on the engine display in the cockpit. About the same time, the captain called for the flaps to be set to 15° and for the before landing checklist. The CVR then recorded a sound similar to flap handle movement, and FDR data showed that the flaps had been selected to 10°. FDR data also showed that the airspeed at the time was about 135 knots.

- At 2216:27.4, the CVR recorded a sound similar to the stick shaker. (The stick shaker warns a pilot of an impending wing aerodynamic stall17 through vibrations on the control column, providing tactile and aural cues.) The CVR also recorded a sound similar to the autopilot disconnect horn, which repeated until the end of the recording. FDR data showed that, when the autopilot disengaged, the airplane was at an airspeed of 131 knots. FDR data showed that the control columns moved aft at 2216:27.8 and that the engine power levers were advanced to about 70° (rating detent was 80°) 1 second later. The CVR then recorded a sound similar to increased engine power, and FDR data showed that engine power had increased to about 75 percent torque.

- FDR data also showed that, while engine power was increasing, the airplane pitched up; rolled to the left, reaching a roll angle of 45° left wing down; and then rolled to the right. As the airplane rolled to the right through wings level, the stick pusher activated (about 2216:34), and flaps 0 was selected. (The Q400 stick pusher applies an airplane-nose-down control column input to decrease the wing angle-of-attack [AOA] after an aerodynamic stall.) About 2216:37, the first officer told the captain that she had put the flaps up. FDR data confirmed that the flaps had begun to retract by 2216:38; at that time, the airplane's airspeed was about 100 knots. FDR data also showed that the roll angle reached 105° right wing down before the airplane began to roll back to the left and the stick pusher activated a second time (about 2216:40). At the time, the airplane's pitch angle was -1°.

- About 2216:42, the CVR recorded the captain making a grunting sound. FDR data showed that the roll angle had reached about 35° left wing down before the airplane began to roll again to the right. Afterward, the first officer asked whether she should put the landing gear up, and the captain stated "gear up" and an expletive. The airplane's pitch and roll angles had reached about 25° airplane nose down and 100° right wing down, respectively, when the airplane entered a steep descent. The stick pusher activated a third time (about 2216:50). FDR data showed that the flaps were fully retracted about 2216:52. About the same time, the CVR recorded the captain stating, "we're down," and a sound of a thump. The airplane impacted a single-family home (where the ground fatality occurred), and a postcrash fire ensued. The CVR recording ended about 2216:54.

Source: NTSB AAR-10/01, ¶1.1.

3

Analysis

- Stall training for the Q400 occurs during three of eight simulator sessions during initial, transition, upgrade, and requalification training. These three simulator sessions included three approach-to-stall profiles—in the clean (cruise flight), takeoff, and landing configurations—that are evaluated during a proficiency check. The company's approach-to-stall profiles were consistent with the FAA's airline transport pilot practical test standards.

- During postaccident interviews, the NTSB learned that, during the approach-to-stall recovery exercises for initial simulator training, pilots were instructed to maintain the assigned altitude and complete the recovery without deviating more than 100 feet above or below the assigned altitude, which had been previously required by the practical test standards for the checkride. Some company check airmen indicated that any deviation outside of that limit would result in a failed checkride, but other company check airmen considered this altitude limitation to be a minimal loss of altitude (which is consistent with the current practical test standards).

- Company training personnel and Q400 check airmen stated that demonstration of the airplane's stick pusher system was not part of the training syllabus for simulator training at the time of the accident. Nevertheless, one check airman indicated that he demonstrated the stick pusher during initial simulator training. The check airman stated that most of the pilots who were shown the pusher in the simulator would try to recover by overriding the pusher.

Source: NTSB AAR-10/01, ¶1.17.1

- The CVR recorded the activation of the stick shaker about 2216:27, and FDR data showed that the activation occurred at an AOA of about 8°, a load factor of 1 G, and an airspeed of 131 knots, which was consistent with the AOA, airspeed, and low-speed cue during normal operations when the ref speeds switch was selected to the increase position. The airplane was not close to stalling at the time. However, because the ref speeds switch was selected to the increase (icing conditions) position, the stall warning occurred at an airspeed that was 15 knots higher than would be expected for a Q400 in a clean (no ice accretion) configuration. Stick shakers generally provide pilots with a 5- to 7-knot warning of an impending stall; thus, as a result of the 15-knot increase from the ref speeds switch, the accident flight crew had a 20- to 22-knot warning of a potential stall.

- CVR and FDR data indicated that, when the stick shaker activated, the autopilot disconnected automatically. The captain responded by applying a 37-pound pull force to the control column, which resulted in an airplane-nose-up elevator deflection, and adding power. In response to the aft control column movement, the AOA increased to 13°, pitch attitude increased to about 18°, load factor increased from 1.0 to about 1.4 Gs, and airspeed slowed to 125 knots. In addition, the speed at which a stall would occur increased.183 The airflow over the wing separated as the stall AOA was exceeded, leading to an aerodynamic stall and a left-wing-down roll that eventually reached 45°, despite opposing flight control inputs. Thus, the NTSB concludes that the captain's inappropriate aft control column inputs in response to the stick shaker caused the airplane's wing to stall.

- The airplane experienced several roll oscillations during the wing aerodynamic stall. FDR data showed that, after the roll angle had reached 45° left wing down, the airplane rolled back to the right through wings level. After the first stick pusher activation, the captain applied a 41-pound pull force to the control column, and the roll angle reached 105° right wing down. After the second stick pusher activation, the captain applied a 90-pound pull force, and the roll angle reached about 35° left wing down and then 100° right wing down. After the third stick pusher activation, the captain applied a 160-pound pull force. The final roll angle position recorded on the FDR was about 25° right wing down. At that time, the airplane was pitched about 25° airplane nose down.

Source: NTSB AAR-10/01, ¶2.2.1

4

Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of this accident was the captain’s inappropriate response to the activation of the stick shaker, which led to an aerodynamic stall from which the airplane did not recover. Contributing to the accident were (1) the flight crew’s failure to monitor airspeed in relation to the rising position of the low-speed cue, (2) the flight crew’s failure to adhere to sterile cockpit procedures, (3) the captain’s failure to effectively manage the flight, and (4) Colgan Air’s inadequate procedures for airspeed selection and management during approaches in icing conditions.

Source: NTSB AAR-10/01, ¶3.2

References

(Source material)

NTSB Aircraft Accident Report, AAR-10/01, Loss of Control on Approach, Colgan Air, Inc., Operating as Continental Connection Flight 3407, Bombardier DHC-8-400, N200WQ, Clarence Center, New York, February 12, 2009.